Obstructed Defecation Syndrome

Top Contributors - Khloud Shreif, Temitope Olowoyeye, Kim Jackson and Aminat Abolade

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

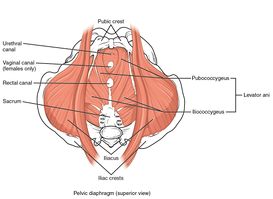

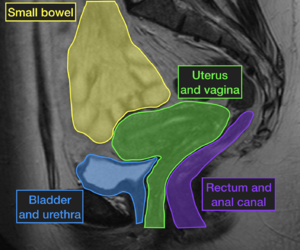

The levator ani muscles as a component of pelvic floor diaphragm ( the iliococcygeus, the pubococcygeal, and the puborectalis muscles) in addition to its role as a supportive structure and keeping visceral and internal organs in place. levator ani muscles specifically puborectalis have a role to maintain the urinary and fecal continence, contraction, and relaxation of puborectalis, lower abdominal muscles, and anal sphincter work synchronically for normal and smooth defecation.

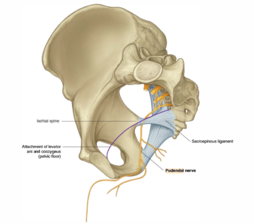

The pudendal nerve innervates the external anal sphincter and part of the puborectalis muscle, with frequent and prolonged straining that may stretch the pudendal nerve causing pudendal neuropathy.

While we have voluntary control over the external anal sphincter the internal anal sphincter muscles are involuntary muscles affected by the rectum, it is relaxed if the rectum filled with stool and vice versa, so the sensitivity of the rectum is important for normal physiology.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Obstructive defecation syndrome ODS is a term related to constipation, and one of the underlying causes of fecal incontinence, it is a common condition of inability of a person to evacuate the rectum properly/ reduce bowel movement and may be associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Sometimes symptoms of fecal incontinence and constipation overlap.

In general the pathogeneses of ODS varying from:

- Neurological origin (multiple sclerosis, spinal cord lesions, and pudendal neuropathy that impaires rectal sensitivity cause excess distension and stretch of the rectal wall, paradoxical rectal contractions and overflow incontinence can happen[1].

- Muscular origin such as (pelvic floor dyssynergia, anismus)

- Psychological origin (anxiety and spastic colon).

- Organ/ mechanical origin, cases of rectocele, outlet rectal obstruction, or intussusception obstruction is defined as overlapping of a part of intestine to the adjacent part blocking the passage of food and fluid.

Cases of rectal prolapse, rectocele most common in female. and internal rectal mucosal prolapse are most common associated and found in patient with ODS[2].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The patient will have symptoms of the need to strain with bowel movement, episodes of incomplete evacuation, fragmented stool, pelvic heaviness, and sometimes accidental bowel leakage.

Frequent, prolonged straining becomes the prime mover. may cause stretch on the pudendal nerve and pudendal neuropathy causing rectal hyposensation, internal organ descends (prolapse), muscle weakness, and spending too much time than usual in toilet.

Lower abdominal/rectal pain, feeling of incomplete evacuation of the rectum. The patient will tend to use perineal manipulation to help with the evacuation.

Pat with ODS will have a small, more hard stool and difficulty to evacuate, responses to laxatives and enema, and less effective to trigger the peristaltic reflex[1].

Fecal incontinence one of the symptoms of ODS.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Protogram image: functional test use barium contrast medium go through the rectum, used in cases complain of incontinence or difficulty on defecation and passage of stool to study the lower bowel movement, the image is taken during attempt to defecate and used commonly to detect rectocele.

The colonoscopy: rule out rare causes of obstructive defecation tumors for example.

Anorectal manometry: a primary diagnostic test to assess rectum hyposensitivity, use inserted ballon into rectum fill with water or air to trigger the need for evacuation.

Electromyography (EMG): they used o assess the strength and coordination of pelvic floor muscles around the anus, vagina, and the movement of rectum during defecation.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Obstructed Defecation Syndrome score: consists of 5 items each item graded from 0-5, as 0 no symptoms and 20 sever symptoms[3].

| Symptoms | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive straining Rarely Sometimes Usually Always | Never | rarely | sometimes | usually | always |

| Incomplete rectal evacuation | Never | rarely | sometimes | usually | always |

| Vaginal/Perineal digital pressure | Never | rarely | sometimes | usually | always |

| Abdominal discomfort/pain | Never | rarely | sometimes | usually | always |

| Use of enemas/laxative | Never | rarely | sometimes | usually | always |

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment[edit | edit source]

Change in dietary regimen

The patient advised to stop foods that increase stool viscosity like chocolate, drink plenty of water, and concentrate on food rich in fibers as it affects on consistency of stool and help in digestion of other types of food[1]. Psyllium: another form of fibers was introduced in diet, according to a RCT found that diet rich in psyllium reduces the conscious rectal sensitivity threshold than fiber diet after rehabilitation of ODS[4].

Yoga, psychotherapy, and relaxation exercises all help with bowel movement.

Biofeedback therapy[5]

Is the first step in the treatment of patient with ODS mainly for patients with pelvic floor dyssynergy, some RCT show it is effect is superior to patient education and laxatives[6].

Before start explain to the patient the defecation problems result from un voluntary and unconscious contraction of anus, a rectal manometry (balloon inflated with air or water) and a screen in front of patient to give feedback of performance and how to correct.

In patient with pelvic floor dyssynergia, train the patient to try to relax the pelvic floor muscles during stimulated defecation and instead tighten the abdominal muscles and lower the diaphragm to increase the intra-abdominal pressure and push the stool[6]

Surgical intervention[edit | edit source]

surgical interventions should be carried if the conservative treatment failed and there is structural or organ origin for the problem such as in some cases of rectocele, rectal obstruction, or intussusception.

Rectocele can be managed via pelvic floor rehabilitation as long it isn’t significant and don’t become larger.

Surgical interventions divided into: transvaginal, transabdominal and transanal. Transanal procedures. Surgers show short term effect and resolve of the problem,but long-term results are still under discussion.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Podzemny V, Pescatori LC, Pescatori M. Management of obstructed defecation. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2015 Jan 28;21(4):1053.

- ↑ Linardoutsos D. Assessment and Treatment of Obstructed Defecation Syndrome. InCurrent Topics in Faecal Incontinence 2019 May 22. IntechOpen

- ↑ Renzi A, Brillantino A, Di Sarno G, d’Aniello F. Five-item score for obstructed defecation syndrome: study of validation. Surgical innovation. 2013 Apr;20(2):119-25.

- ↑ Pucciani F, Raggioli M, Ringressi MN. Usefulness of psyllium in rehabilitation of obstructed defecation. Techniques in coloproctology. 2011 Dec;15(4):377-83.

- ↑ Murad-Regadas SM, Regadas FS, Bezerra CC, de Oliveira MT, Regadas Filho FS, Rodrigues LV, Almeida SS, da Silva Fernandes GO. Use of biofeedback combined with diet for treatment of obstructed defecation associated with paradoxical puborectalis contraction (anismus): predictive factors and short-term outcome. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2016 Feb 1;59(2):115-21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wald A, Bharucha AE, Cosman BC, Whitehead WE. ACG clinical guideline: management of benign anorectal disorders. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG. 2014 Aug 1;109(8):1141-57.[1]