Nocebo Effect

Original Editor - Melissa Coetsee

Top Contributors - Melissa Coetsee, Kim Jackson and Vidya Acharya

Introduction[edit | edit source]

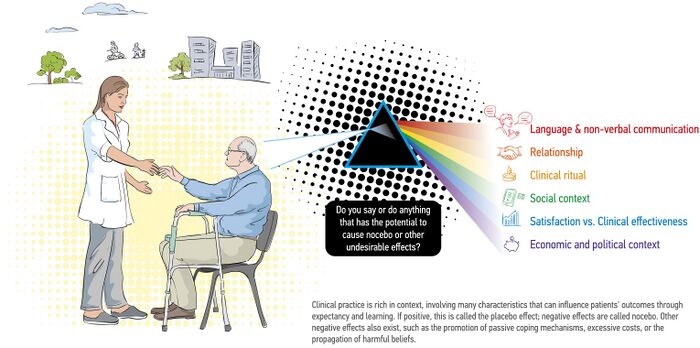

The nocebo effect, the opposite of the placebo effect, is when the expectation of a negative outcome precipitates the corresponding symptom or leads to its exacerbation.[1] In contrast to the placebo effect of positive expectation which results in health benefits, the nocebo effect worsens the health status due to negative beliefs and expectations. It refers to the adverse outcomes that occur as a result of patient expectations and subconscious learning [2]. Originally these terms were used for 'inactive' treatments (eg. sugar pill), but the words we use are an integral part of these effects.[3]

Factors that contribute[edit | edit source]

The following factors can contribute to a nocebo effect[2]:

- The healthcare setting

- Patient-practitioner interaction (verbal and non-verbal communication)

- Patient-practitioner characteristics (reputation, previous negative experiences)

- Actions that convey meaning

- Words/language that have negative meaning attached to them

- Social media/pamphlets focusing on disease and biomedical models

Manifestation of Nocebo Effect[edit | edit source]

- Aggravation of pain, not related to disease/treatment factors

- Treatment 'side-effects'

- Learnt helplessness; loss of self-efficacy and self-esteem

- Fear avoidance

- Over-reliance on medical care

Physiology[edit | edit source]

For a long time, the placebo and nocebo effects were largely explained by psychological mechanisms, but research has revealed that biological factors are also involved. Some of the physiological mechanisms which are activated by negative expectancy include[2][4]:

- Activation of the pronociceptive system

- Activation of various cortical and spinal cord mechanisms - Increased anxiety which activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- Affects neural pathways that mediate pain experience

Evidence of Nocebo Effects[edit | edit source]

A meta-analysis has demonstrated that the effect sizes related to verbally induced nocebo can be significant [2]

- ICU[5]

- Postural Stability[6]

- Low back pan: Routine imaging leads to worse outcomes compared to a clinical report (reassurance of incidental findings). Early MRI's for LBP results in longer length of disability, higher medical cost and worse outcomes regardless of radiculopathy (after controlling for severity and demographics)[3]

- Hyperalgesia: Higher levels of fear of pain significantly increases stress levels and is associated with increased nocebo hyperalgesia[3]

- Medical Imaging: many people receive routine scans and radiographs, which are considered the gold standard to determine the pathoanatomical source of their symptoms. use of negative words to describe a non-threatening situation; for example, diagnostic descriptions of imaging reports perceived by patients as implying an increased severity of their condition[2]

Language Matters[edit | edit source]

Healthcare is infiltrated with meaning and words, from the jargon of medical terms to the waiting room, interview, relaying of information and clinical mannerisms - which can all influence outcomes.[4] Research has shown that good communication forms an integral part of efficient and quality health care. Not only does the way medical information is delivered matter, but the words used by clinicians can have a significant impact on patient outcomes.[7]

Pathoanatomical language still dominates the health care sector, with less acknowledgement of the well researched psychological factors involved in pain and disability[8]. An improved understanding of pain as a phenomenon that is mediated by the mind may help to increase awareness of the meaning behind the words we choose.

Communication[edit | edit source]

Patient-clinician communication[9]

Especially, reconceptualising pain as a complexly influenced and emergent phenomenon rather than a linear consequence of tissue damage is warranted. [2]

Words[edit | edit source]

Like medication, words can change the way a person thinks and feels:[8]

- Words can generate good or bad emotions

- Words can prompt actions that can lead to negative or positive behaviour change

- The meaning attached to words are influenced by one's background and culture - the word degenerative discs may sound non-threatening to a clinician, but scary to a patient

Quote: "Words are, of course, the most powerful drug used by mankind" - Rudyard Kipling

Emotive power of words[7]

Ethics[edit | edit source]

Informed Consent[edit | edit source]

One of the basic ethical duties in health care is to obtain informed consent from patients before treatment; however, the disclosure of information regarding potential complications or side effects that this involves may precipitate a nocebo effect.[1]

Reframing Words[edit | edit source]

“To encounter another human is to encounter another world.” With this in mind, there cannot be one simple recipe or formula for how we might use language within clinical practice. Not all medicalized language is harmful to all individuals[8]

- Problem framing

- Patient engagement

- Positivity: focus on factors that eliminate worry and fear; focus on language towards hopes, and not hurts; focus on what one can do rather than what can't be done

In rehabilitation[2][edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation professionals need to be aware of the following actions and their possible negative effects on patient outcomes[2]:

- Using unhelpful diagnostic labels - can promote fear of movement and catastrophising, and can create negative expectancy

- Failure to focus on positive aspects of structures in the human body - can lead to false perceptions of vulnerability and lead to fear-avoidance

- Excessive attention to tissue modification induced through treatment - reinforces dependence, discourages self-management and promotes beliefs in purely biological causes of pain

- Over-emphasis on teaching 'proper' postures - triggers fear and limits contextual adaptation

- Overuse of low-value-based therapies (such as electrotherapy) - delayed recovery and dependence which could result in lack of self-efficacy and negative expectations

Examples in the literature

- A study found that when patients with low back pain are told that a leg flexion test could lead to pain, reported an increase in pain and performed fewer repetitions, than those who were told the test is painless[10].

- Healthcare advice that emphasises structural/anatomical vulnerability of the spine from radiographic imaging, resulted in patients having greater reported disability.[11]

- Various studies have reported that chronic back pain can in part be iatrogenic due to misconceptions and negative beliefs instilled by practitioners.[11]

- Suggestions or practices that could promote the belief that deterioration is inevitable without continuous intervention/'maintenance' therapy.

| Harmful words | Reframed wording |

|---|---|

| Instability | Needs more strength and control |

| Chronic | It may persist, but you can overcome it |

| Bone out of place/ subluxation | |

| Lumbar dysfunction/ disc bulge | Episode of back pain; lumbar sprain |

single and at times offhand statements can heavily influence recovery expectations.

Inappropriate Routine use of medical imaging-

| Harmful Words | Reframed Wording |

|---|---|

| Wear and tear (may imply the need for a technical fix); Degenerative changes | Normal age changes |

You have to do X before "..."

|

If you do X, you can "..."

|

| You have the joint of an 80-year old | |

| Your joint is bone on bone | A lot of people without pain also have this; narrowing/tightness |

| That is the worst joint I have ever seen | The good news is, we can help |

| No wonder you are in pain | This doesn't have to be a life sentence to pain |

| Tear | Pull |

| Trapped nerve | Tight, but can be stretches/mobilised |

| Bulge/herniation | Bump, swelling |

| You are going to have to live with this | You may need to make some adjustments |

Clinical Implications[edit | edit source]

It is important to be aware of the impact that words (when we educate, interview, assess) can have on patient expectations, and subsequently on health outcomes. Clinicians who have short interactions with patients, need to carefully consider what to say and convey in the limited time, and those who have prolonged contact with patients (such as allied health practitioners) should continually focus on positive reframing and challenge negative beliefs.[4]

It is not ethical to use positive words, which are in fact false (eg. telling a patient they will definitely recover fully, when this is not the case). One can however leverage the positive effects of words to make the art and science of medicine work together, by combining evidence based interventions with a positive therapeutic experience.[4]At the same time, the effect of evidence-based interventions are at risk of being minimised when combined with a negative therapeutic experience.

We can shape our therapist-patient communication, patient treatment expectations, and clinic design and atmosphere, to name a few examples.[4]In each patient encounter, we should strive to discover the patient's expectation and then deliver and exceed it to the extent that it doesn't cause more harm. If a patient's expectation could cause harm (eg, an early magnetic resonance imaging scan the patient doesn't need), the onus is then on each of us to reshape the patient's beliefs to be consistent with best practice.

realistic without being fatalistic.

As clinicians, we need a keen sensitivity to how our patients are responding to the words we use.

In summary, all musculoskeletal conditions must be viewed within a more comprehensive framework that takes account of biomedical issues and includes how patients perceive their injuries, their disabilities, their pain, and how they make sense of what is happening to them. The words we (and our patients) use are crucial to this more comprehensive view. Eccleston and Crombez8 state, “Pain is an ideal habitat for worry to flourish.” Without such a reconceptualization, clinicians will likely remain unaware of the potential harm that their words may hold. As a result, they may continue to unknowingly fertilize pain's vulnerable ground.[8]

COP are well-placed to provide primary health care that reduces requests for imaging, strong analgesic medications, and invasive pain treatments, and to mitigate the commonly-held belief that where there is pain there must be an injury. COP practitioners could do so by triaging, providing patient-focussed communication and supportive relationships, helping to re-engage in physical activity and providing short-term symptom relief, and by increasing their focus on advocacy for patients. To effectively redirect patients’ journeys away from provider-shopping and consecutive disappointments, long-term educational efforts at profession-level need to be paired with public outreach campaigns and the disincentivizing of passive low-value care.[2]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

- x

or

- numbered list

- x

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cohen S. The nocebo effect of informed consent. Bioethics. 2014 Mar;28(3):147-54.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Hohenschurz-Schmidt D, Thomson OP, Rossettini G, Miciak M, Newell D, Roberts L, Vase L, Draper-Rodi J. Avoiding nocebo and other undesirable effects in chiropractic, osteopathy and physiotherapy: An invitation to reflect. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2022 Oct 21:102677.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Dorow B. Words that Hurt, Words that Heal. [PowerPoint presentation]. Kaiser Permanente Persistent Pain Fellowship.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Benz LN, Flynn TW. Placebo, nocebo, and expectations: leveraging positive outcomes. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2013 Jul;43(7):439-41.

- ↑ Huynh KN, Rouse-Watson S, Chu J, Lane AS, Cyna AM. Unheard and unseen: The hidden impact of nocebo communication in the Intensive Care Unit. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2023 Nov 29:17511437231214148.

- ↑ Russell K, Duncan M, Price M, Mosewich A, Ellmers T, Hill M. A comparison of placebo and nocebo effects on objective and subjective postural stability: a double-edged sword?. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2022 Aug 18;16:967722.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Vranceanu AM, Elbon M, Ring D. The emotive impact of orthopedic words. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2011 Apr 1;24(2):112-7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Stewart M, Loftus S. Sticks and stones: the impact of language in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2018 Jul;48(7):519-22.

- ↑ Colloca L, Finniss D. Nocebo effects, patient-clinician communication, and therapeutic outcomes. Jama. 2012 Feb 8;307(6):567-8.

- ↑ Pfingsten M, Leibing E, Harter W, Kröner-Herwig B, Hempel D, Kronshage U, Hildebrandt J. Fear-avoidance behavior and anticipation of pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Pain medicine. 2001 Dec 1;2(4):259-66.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lin IB, O'Sullivan PB, Coffin JA, Mak DB, Toussaint S, Straker LM. Disabling chronic low back pain as an iatrogenic disorder: a qualitative study in Aboriginal Australians. BMJ open. 2013;3(4).