Muscle Length Assessment and Treatment Related to Patellofemoral Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) (Updated categories) |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | [[Category:Course Pages]] | ||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | [[Category:Plus Content]] | ||

Revision as of 15:45, 22 August 2022

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Patellofemoral pain is often the result of a cumulative load. It reveals itself with prolonged and or repetitive activity or holding of a certain position. Subtle changes in load can add up over time to a large load.[1] Thorough assessment and subjective interview will provide clues to causative factors of the patient's patellofemoral pain.

For a review of the gait cycle, please read this article.

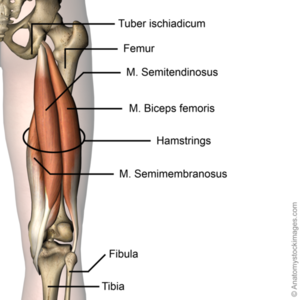

Hamstrings[edit | edit source]

Why is it mechanically relevant to assess?

- Tight, tense, and shortened hamstrings can pull the knee into excessive knee flexion. This can result in a greater knee flexion moment at initial contact or heel strike part of the gait cycle.

- Any resulting increase in knee flexion will increase the patellofemoral contact pressures. Therefore it is important to avoid the situation where the tibia is being pulled back and there is enhanced knee flexion.[1]

How should we assess and test for the muscle length?

- It is important to assess hamstring length in conjunction with stride length

- Bedside clinical exams: sit-and-reach, straight leg raise

- It is important to assess and compare the muscle length of both hamstrings. The rehabilitation professional should also take the patient's relative flexibility into consideration, ie: is this patient's body overall flexible or tight. This will help determine the patient's muscle length norm.

- Other muscle groups to assess: gluteal extensors

- Clues from the patient interview or past medical history: a patient may state that they stretch regularly but have not noticed any change in their flexibility, histories of repeated injury to a muscle group might mean that it's got more scarring in the intramuscular matter, having regular repeating injuries.[1]

What can we do to treat?

- The literature gives little insight to the duration or frequency of stretching[1]

- Consistent, regular stretching that the patient will be able to complete is key. Talk about the patient's schedule and lifestyle and help them create an exercise programme they will be able to stick to and faithfully perform. Create easy, pragmatic exercises the patient will most likely complete.[1]

- Types of hamstring stretches: (1) standing static stretch, (2) dynamic stretching, (3) hold-relax (also known as contract-relax).

- There is some literature support that dynamic stretching is slightly more effective.[1] In patients with inflexible hamstrings, dynamic hamstring stretching improved muscle activation time and clinical outcomes compared with static hamstring stretching, when both were combined with strengthening exercises.[2] Hold-relax stretching tends to decrease muscle tone which allows the stretch to be deepened. However, it is important to create an exercise programme that is best suited for the patient.[1]

To learn more about the types of stretches and how stretching effects muscle anatomy and physiology, please read this article.

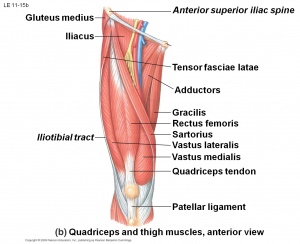

Quadriceps[edit | edit source]

Why is it mechanically relevant to assess?

- Look for clues in the patient's subjective interview and past medical history

- If the patient reports pain in the knee with prolonged sitting with knee flexed, it is important to rule out: (1) no quadricep strength issues, (2) no gluteal strength issues, (3) no foot posture issues, (4) no load issues when considering quadricep length issues.

- So, when we sit for a prolonged period with tight quads, we have a large compressive vector through our patellofemoral joint, which might be tolerated for a short while, but after a while that pressure in the subchondral bone can go up and up and up and they get to the point where the only way they can alleviate that pressure pain is to straighten out their leg.[1]

How should we assess and test for the muscle length?

- Bedside clinical exams: modified Thomas Test.

- When performing this test, when the knee is flexed and hip comes into more flexion, part of the tightness is rectus femoris; if the hip does not flex, then it is more tightness in the vastii muscles.

- If the patient has some quadriceps tightness, the knee will maintain 45-60 degrees knee flexion. This signals that it is hanging on quadricep tension. And when they are passively moved to 90 degrees knee flexion, the examiner can feel the level of resistance in the muscle.

- Cinema Sign (also known as Theatre sign, Movie-goers sign, Movie sign): Pain in the knee resulting from the compression in the patellofemoral joint by tight quadricep muscles with prolonged sitting with knee flexion.[1]

What can we do to treat?

- Stretching of the quadricep is needed, but may need to be modified dependent on the patient's level of tightness.

- If the patient is currently experiencing a sore patellofemoral joint, performing a classic standing quadricep stretch will most likely exacerbate their pain. This stretch can be modified by standing with a behind them, their foot supported on the chair, and provide verbal cues to "stand tall and imagine a helium balloon attached to your breastbone, pulling you up."

- If the patient is not irritated, they can perform a hold-relax (contract-relax) in the same modified position described above and pushing the foot down into the chair and perform an isometric hold for 10 seconds.[1]

- The patient can also attempt flexibility gains with eccentric exercise. However, patients with patellofemoral pain often will not tolerate exercises that take them eccentrically to end range.[1]

- There is a small amount of emerging evidence looking at dry needling to trigger points in the vastii as being preferential to sham needling for patellofemoral pain management. A2020 study by Ma et al found that dry needing of the quadriceps, when combined with stretching can reduce pain, improve function, and the coordination of VMO and VL in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome.[3]

- Foam rolling[1]

What does the literature say?

- Bethel et al 2022 studied the effects of a 7-week stretching programme on healthy adults. They found that completing three sets of a three stretch programme, three times per week created a significant decrease in the muscle fibre angle in both the vastus medialis oblique (VMO) and the vastus lateralis (VL).[4] To learn more about changing the muscle architecture of the quadriceps, please read this article.

- Torrente et al 2022 looked at the effects of self myofascial release using a foam roller on hypertrophy of the quadriceps. The study found that a 7-week programme of self myofascial release resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the pennation angles of both the VMO and VL in healthy adult males.[5]

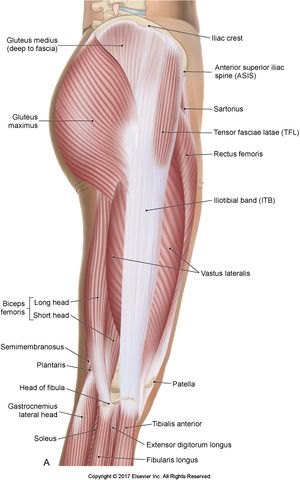

Iliotibial Band[edit | edit source]

Why is it mechanically relevant to assess?

The iliotibial band (ITB) can be a controversial anatomical structure. It is very strong and thick, and it is not capable of changing length.[1]

"Gratz investigated the tensile properties of human TFL muscle and found similarities with those of “soft steel”, based on its tendon-like histologic structure comprised of an inconspicuous number of elastic fibers."[6]

The origins of the ITB are contractile: the tensor fascia lata (TFL) and the gluteus maximus. If there is muscle tension or hypertrophy causing a shortening of the soft tissue structures, then it is going to proximise the ITB. This can cause two issues which can irritate the patellofemoral joint: (1) it can cause a lateral tilt of the patella and (2) through its tibial attachment beyond about 60 degrees of knee flexion, it can externally rotate the tibia. This ultimately will create a functional knee valgus moment, a large Q-angle, which can overload the lateral patellofemoral joint.[1]

- The patient may reveal that, in addition to their patellofemoral pain, they have some pain at the side of their pelvis when walking. This may indicate that they have a tight and overactive TFL as well.

- They may have a positive cinema sign, but it is more enhanced when legs are crossed.[1]

How should we assess and test for the muscle length?

- Bedside clinical exams: Obers test (however this can be a challenging position for patients to maintain and for the clinician to fully assess all needed angles).[1]

What does the literature say? Kwan et al 2021 looked at the relationship between hip adduction and patellar position as an alternative to the Obers test. Excessive hip adduction can lead to knee valgus and increased Q-angle which predisposes the patient to patellar displacement. This phenomena is caused by the tightening of the ITB during hip adduction which places stress on the lateral retinaculum, and leads to lateral patellar movement. This study found that hip adduction consistently produced a smaller patella-condyle distance than the neutral position. This indicates a lateral patellar displacement which could increase the relative load on the lateral patellofemoral joint and cause pain. This study also demonstrated that ultrasound was a reliable assessment tool for patella displacement.[7]

What can we do to treat?

- Manual therapy for myofascial release on contractile tissues of the ITB

- Instrument assisted soft tissue release using a spiky massage ball, particularly on TFL.

- Leaning against the wall for provide pressure over contractile tissues of the ITB

- Trialing a variety of stretches which effect the contractile tissues and assess which give the best relief. The most affective can be added to the patient's home exercise programme.[1]

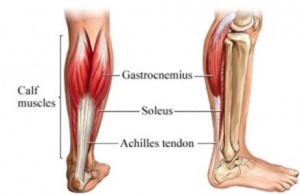

Gastrocnemius and Soleus[edit | edit source]

Why is it mechanically relevant to assess?

- During the gait cycle, heel strike occurs at initial contact then the tibia must translate over the foot in midstance. Tightness in the calf muscles can prevent this from happening. To compensate patients with tight calf muscles will: (1) move into excessive pronation or (2) will have an early heel rise in the gait cycle. Both of these compensations have negative effects on the patellofemoral joint causing tibial rotation and patellofemoral pain, and increasing patellofemoral contact pressure respectively.[1]

- A study performed in 2015 showed that people with osteoarthritic patellofemoral joints have more bone oedema in their patellofemoral joint if they have increased knee flexion at the end of their gait cycle.[8] This can be caused in two ways: (1) tight calf muscles or (2) tight hip flexors which limit the ability to get into hip extension. This will make the patient have to flex the knee to offload the hip.[1]

- The patient may reveal that they stretch often but that their calves will not stop cramping or are always tight. In these cases, it is important to assess their hip flexor endurance. The patient may be pushing through their calves to compensate from lack of ability to pull through their hip flexors.[1]

How should we assess and test for the muscle length?

- It is important to distinguish between the gastrocnemius and soleus.

- Assess for the gastrocnemius with the straight knee, soleus with a flexed knee. Testing can be done in supine for either muscle, or the standing knee-to-wall test for the soleus.[1]

What can we do to treat?

- Manual therapy for myofascial release or instrument assisted soft tissue release

- Foam rolling

- Dynamic stretching[1]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Optional Suggested Physiopedia Pages:

Additional Optional Reading:

- Bethel J, Killingback A, Robertson C, Adds PJ. The effect of stretching exercises on the fibre angle of the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis oblique: an ultrasound study. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2022;34(2):161-6.

- Fredericson M, White JJ, MacMahon JM, Andriacchi TP. Quantitative analysis of the relative effectiveness of 3 iliotibial band stretches. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2002 May 1;83(5):589-92.

- Torrente QM, Killingback A, Robertson C, Adds PJ. The effect of self-myofascial release on the pennation angle of the vastus medialis oblique and the vastus lateralis in athletic male individuals: an ultrasound investigation. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2022;17(4):636.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 Robertson, C. Patellofemoral Joint Programme. Muscle Length Assessment and Treatment Related to Patellofemoral Pain. Physioplus. 2022.

- ↑ Lee JH, Jang KM, Kim E, Rhim HC, Kim HD. Effects of static and dynamic stretching with strengthening exercises in patients with patellofemoral pain who have inflexible hamstrings: a randomized controlled trial. Sports health. 2021 Jan;13(1):49-56.

- ↑ Ma YT, Li LH, Han Q, Wang XL, Jia PY, Huang QM, Zheng YJ. Effects of trigger point dry needling on neuromuscular performance and pain of individuals affected by patellofemoral pain: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Pain Research. 2020;13:1677.

- ↑ Bethel J, Killingback A, Robertson C, Adds PJ. The effect of stretching exercises on the fibre angle of the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis oblique: an ultrasound study. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2022;34(2):161-6.

- ↑ Torrente QM, Killingback A, Robertson C, Adds PJ. The effect of self-myofascial release on the pennation angle of the vastus medialis oblique and the vastus lateralis in athletic male individuals: an ultrasound investigation. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2022;17(4):636.

- ↑ Seeber GH, Wilhelm MP, Sizer Jr PS, Guthikonda A, Matthijs A, Matthijs OC, Lazovic D, Brismée JM, Gilbert KK. The tensile behaviors OF the iliotibial band–a cadaveric investigation. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2020 May;15(3):451.

- ↑ Kwan LY, Killingback A, Robertson C, Adds P. Ultrasound investigation into the relationship between hip adduction and the patellofemoral joint. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2021;33(7):511-6.

- ↑ Teng HL, MacLeod TD, Link TM, Majumdar S, Souza RB. Higher knee flexion moment during the second half of the stance phase of gait is associated with the progression of osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint on magnetic resonance imaging. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Sep;45(9):656-64.