Lumbar Strain

Original Editors - Pieter Jacobs

Top Contributors - Bo Hellinckx, Hannah Willocx, Sarah Harnie, Lynn Leemans, Kim Jackson, Elodie Baele, Nel Breyne, Lilian Ashraf, Wanda van Niekerk, Olajumoke Ogunleye, WikiSysop, Lucinda hampton, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Rachael Lowe and Naomi O'Reilly - Bo Hellinckx - Lynn Leemans - Nel Breyne - Sarah Harnie

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Lumbar strain accounts for 70% of mechanical low back pain.[1] It is defined as over stretch injury or tear of paraspinal muscles and tendons in the low back.[2][3]Much of the knowledge of lumbar strain is extrapolated from peripheral muscle strains. (Depalma 2011)

In strains, the muscle is subjected to an excessive tensile force leading to the overstraining of the myofibres and consequently to their rupture near the myotendinous junction. (Jarvinen 2007, Depalma 2011)

The current classification of muscle injuries identifies mild, moderate and severe injuries based on the clinical impairment they bring about. (Jarvinen 2007)

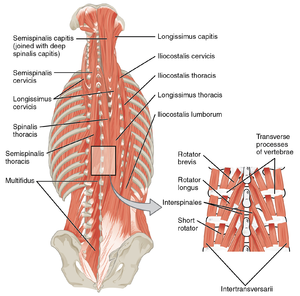

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The lumbar spine consists of 5 movable vertebrae numbered L1-L5. The complex anatomy of the lumbar spine is a remarkable combination of these strong vertebrae, multiple bony elements linked by joint capsules, and flexible ligaments/tendons, large muscles, and highly sensitive nerves. It also has a complicated innervation and vascular supply.

The lumbar spine is designed to be incredibly strong, protecting the highly sensitive spinal cord and spinal nerve roots. At the same time, it is highly flexible, providing for mobility in many different planes including flexion, extension, side bending, and rotation.[18] [level of evidence: 5] [19] [level of evidence: 2C]

Lumbar strain can originate in the following muscles (Houglum 2001, Putz 1997, Meeusen1 2001): M. erector spinae (M. iliocostales, M longissimus, M. spinalis) M semispinales, Mm multifidi, Mm rotatores M. quadratus lumborum M. serratus posterior.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Strains are defined as tears (partial or complete) of the muscle-tendon unit. Muscle strains and tears most frequently result from a violent muscular contraction during an excessively forceful muscular stretch from lifting heavy objects or sudden twisting motions[4]. Any posterior spinal muscle and its associated tendon can be involved, although the most susceptible muscles are those that span several joints. Acute and chronic lumbar strain pain can be defined as: acute pain is most intense 24 to 48 hours after injury. Chronic strains are characterized by continued pain attributable to muscle injury. [13] [level of evidence: 2C]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Low back pain is the second most common symptom that causes patients to seek medical attention in the outpatient setting. Approximately 70% of adults have an episode of LBP as a result of work or play.

Exact numbers regarding the international frequency of low back injuries are not known. Studies done in The United States have shown that 7-13% of all sports injuries in intercollegiate athletes are low back injuries. The most common back injuries are muscle strains (60%) and disc injuries (7%). Athletes are more likely to sustain injuries in practice (80%) than during competition (6%).[10] American football (17%) and gymnastics (11%) are reported to have the highest rates of low back injury.[10] [ level of evidence: 2C]

A recent French study reported over 50% of French individuals aged 30-64 years had experienced at least 1 day of LBP over the previous 12 months. 17% had suffered LBP for more than 30 days in the same 12-month period.[11] [level of evidence 3]. The authors noted that the prevalence of LBP varied between men and women. There was an increased incidence with increasing age for LBP that lasted more than 30 days. These data were similar to those of other countries.

In an African study, the mean LBP point prevalence among adults was 32%, with an average 1-year prevalence of 50% and an average life-time prevalence of 62% [12] [level of evidence: 1A]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The onset of lumbar strain could be sudden after trauma or gradual due to persistent stress.[2] The clinical presentation includes pain in the lumbar muscles or nonspecific pain.[2] The pain could be exacerbated during standing and twisting motions, with active contractions and passive stretching of the involved muscle increasing the pain. (2) (level of evidence 5)

Other symptoms are point tenderness, muscle spasm, possible swelling in and around the involved musculature, a possible lateral deviation in the spine with severe spasm and a decreased range of motion. (3)(level of evidence:2A)

Differential Diagnosis[1][edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Laboratory tests: No abnormalities. [5] (Level of evidence: 3B)

Radiographs: Imaging is not indicates unless there are:

- Red flag signs

- Radicular or abnormal neurological clinical features

- Symptoms have persisted for more than a month

In these cases, it is important to exclude other differential diagnosis, by using X-rays or MRI.[6] (Level of evidence: 5)

Examination[edit | edit source]

Evaluation should be done by taking a thorough history from the patients that include the pain location, intensity, aggravating and relieving activities, description of previous pain episodes and to identify any red flags.[7]

1.Inspection [8](level of evidence:5) [14](level of evidence:5)

- Inspect the spine for abnormal curvatures (f.e. scoliosis) or Erythema.

- Observe the gait (posture and movement)let the patient walk across the room, turn around and let him come back. -Observe the seated position of the patient abnormal posture caused by pain and muscle spasm.

2.Palpation

- Tenderness in the midline or paraspinal.[7]

3.ROM

- Flexion of the back -Signs of limited range of motion or a decreased lumbar lordosis .[8]

4.Special tests

- Neurovascular assessment (L4-S1)

Test heel and toe walking °Positive test: marked asymmetry

- SLR± ankle dorsiflexion

Positive test: radiated pain into calf

- Crossed SLR

Pain in the affected limb, when testing the unaffected limb

- SLR + Lasègue

- Bowstring sign

SLR until pain, then flex the knee.

Positive test: reduces pain when nerve is irritated

- Faber test

Flexion Abduction External Rotation of the hip

Pain in SIJ pathology

- One leg extension test

standing on 1 leg with the back in extension

pain can indicate spondylolysis

- Hamstring flexibility

- Leg length evaluation[8]

Measure from ASIS to medial malleolus (cm)

The neurological tests are mostly negative and a lumbar strain is not accompanied by paresthesias or weakness in the legs or feet. Patients with lumbar spine are tender to palpation in the lower back. Other physical findings are loss of normal lumbar lordosis and spasm of the paraspinal muscles. The SLR’s may cause pain in the lower back just like other tests that cause spinal motion. Often there’s an antalgic posture.[9]

Medical Therapy[edit | edit source]

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended in the acute phase to help reduce the swelling and inflammation.[8](level of evidence:1A)

Diclofenac (voltaren)

Ibuprofen(ibuprin,advil,motrin).

Cox-2 selective NSAID’s ( less effects on the gastrointestinal tract)

- Muscle relaxants can also be prescribed to treat muscle spasms and facilitate light physical therapy.[8] 1A)

- No studies support the use of oral steroids in patients with acute low back pain. [9] (level of evidence 2A)

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

From the principles of treatment is preserving the spine motion segment by avoiding shearing and stretching forces on the lumbar motion segment.[7] Also, recent studies have found that continuing ordinary activities within the limits permitted by the pain leads to more rapid recovery than bedrest.[10](level of evidence 1B)

- Cold therapy

In the acute phase of a lumbar strain Cold therapy should be applied (for a short period up to 48 h)to the affected area to limit the localized tissue inflammation and edema.[9] (level of evidence 2A) [8](level of evidence:1A)

- TENS and ultrasound

TENS and ultrasound are often used to help control pain and decrease muscle spasm [11][12]( level of evidence:5)

- Stretching

Mild stretching exercises along with limited activity.

A few stretching exercises: [13](level of evidence: 5)

- Single and double knee to chest

Lie down on your back with your knees bent and your heels on the floor. Pull your knee or knees as close as you can to your chest, and hold the pose for 10 seconds. Repeat this 3 to 5 times.

- Back stretch

Lie on your back, hands above your head. Bend your knees and , keeping your feet on the floor, roll your knees to onse side, slowly. Stay at one side for 10 seconds repeat 3 to 5 times.

- Press up

Begin by laying flat on the ground (face down). When doing this exercise it is important to keep the hips and legs relaxed and in contact with the floor. Keep your hands in line with your shoulders. Inhale, then exhale and press up using the hands keeping the lower half of your body relaxed. Hold until you need to inhale, then move down, lay flat on the ground to rest, and repeat ten times.

- Kneeling lunge(stretching iliopsoas)

- Stretching piriformis

- Stretching quadratus lumborum

- Soft tissue manipulation

Soft tissue manipulation was found to decrease pain and improve ROM.[14]

- Massage

There is insufficient evidence to make a reliable recommendation regarding massage for acute low back pain. There is limited evidence about the use of acupuncture in the treatment of acute low back pain. [9](level of evidence 2A)

- Strengthening exercises

Progression of strengthening exercises should begin once the pain and spasm are under control. The muscles requiring the most emphasis are the abdominals, especially the obliques, the trunk extensors and the gluteals. Placing all of the emphasis in the rehabilitation specifically on the injured muscle is not beneficial. Training the core stability is an important part in the treatment of a lumbar strain and for the further prevention of low back pain. [9] level of evidence 2A)

As with all spinal injuries, posture and body mechanics should be assessed and corrected as needed.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

A Lumbar strain improves within 2 weeks. Normal functions are restored after 4 – 6 weeks. [15](level of evidence 5)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Will JS, Bury DC, Miller JA. Mechanical low back pain. American family physician. 2018 Oct 1;98(7):421-8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Scully R, Rao R. Lumbar Strain and Lumbar Disk Herniation. InOrthopedic Surgery Clerkship 2017 (pp. 481-486). Springer, Cham.

- ↑ Beatty NR, Wyss JF. Lumbosacral Muscle Strain 91. Musculoskeletal Sports and Spine Disorders: A Comprehensive Guide. 2018 Feb 8:395.

- ↑ Kang WW, Kemin S. Clinical observation of the PulStar multiple impulse device in treatment of acute lumbar strain. China Medicine. 2017 Jul;12(7):1039.

- ↑ A.T. Patel, A. A. Ogle; Diagnosis and Management of Acute Low Back Pain; Am Fam Physician. 2000 Mar 15;61(6):1779-1786 (Level of evidence: 3B)

- ↑ A A Narvani, P Thomas an B Lynn. Key topics in sports medicine. Routledge. United Kingdom. 2006. 310p. (Level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Baheti ND, Jamati MK, editors. Physical Therapy: Treatment of Common Orthopedic Conditions. JP Medical Ltd; 2016 Apr 10.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 M.W Van tulder, B.W. Koes. Evidence based handelen bij lage rugpijn. Medicamenteuze behandeling. Bohn stafleu van Loghum 2004 ( level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 14.Karnath B. Clinical Signs of Low Back Pain. Hospital Physician. 2003 May. (level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ Malmivaara, M.D., U. Häkkinen et al. The Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain — Bed Rest, Exercises, or Ordinary Activity.the new England journal of medicine 1995.

- ↑ M. Higgings. Therapeutic exercises. Chapter 19 rehabilitation of the lumbar spine. Davis company 2011. (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ L.D Weiss et al. Oxford amarican handbook of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2010 oxford university press. (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Meeusen R. Sportrevalidatie. Rug- en nekletsels (deel 2) reeks sportrevalidaties. Kluwer.2001. (level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ Li H, Zhang H, Liu S, Wang Y, Gai D, Lu Q, Gan H, Shi Y, Qi W. Rehabilitation effect of exercise with soft tissue manipulation in patients with lumbar muscle strain. Nigerian journal of clinical practice. 2017;20(5):629-33.

- ↑ 8. Gaetano et al. Lumbar strain back to the basics. Sports medicine, 2005 (level of evidence 5)