Ischial Bursitis

Original Editors - Andrea Nees

Top Contributors - Kim Jackson, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Admin, David Olukayode, WikiSysop, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka and Aminat Abolade

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Ischial bursitis, also known as Ischiogluteal bursitis or Weaver’s bottom[1][2] is a rare and infrequently recognized bursitis of the buttock region.[3] It’s one of the four types of hip bursitis. The bursitis is mainly due to chronic and continuous irritation of the bursa and occurs most often in individuals who have a sedentary life.[2][4] Bursitis always develops in response to another pathology. Therefore, the diagnosis of bursitis must be considered as a secondary happening, the primary condition being another pathology. Ischial bursitis can result from sitting for long periods on a hard surface, from direct trauma to the area, or from injury to the hamstring muscle or tendon through activities such as running or bicycling.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The Ischial bursa is a deep located bursa over the bony prominence of the Ischium[5] and lies between the Gluteus Maximus and the Ischial tuberosity.[6][4]

Specifically, the bursa located deep:

- On the sagittal section - between the inferior part of the M. Gluteus maximus and posteroinferiorly part of the Ischial tuberosity.

- On the transverse and coronal sections - the superior end of the bursa abutted to the inferomedial surface of the Ischial tuberosity and it lies medial to the common tendon of the hamstrings muscles that has his insertion from the inferolateral surface of the Ischial tuberosity.[4]

When the bursa is larger, it is possible that it is located in the subcutaneous fat at the ischiorectal fossa, beyond the imaginary line that can be drawn between the medial ends of the gluteus maximus and adductor magnum muscles on the transverse sections.[4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Common causes of bursitis include:

- Trauma (hemorrhagic bursitis)

- Inflammation (rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathies),

- Infection and crystal deposition. There are three basic crystal-induced arthropathies: monosodium urate crystal deposition disease(gout); calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystal deposition disease (pseudogout and other clinical presentation); and calcium hydroxy-apatite (HA) crystal deposition disease.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Pain in the region of the ischial tuberosity which may also radiate to the lower leg[1] [7]

- Pain is aggravated by prolonged sitting[8]

- Tenderness may occur over the ischial tuberosity.[9]

- Inability to sleep on the affected hip.

- Regional muscle dysfunction.[7]

- Swelling and limited mobility.[10]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Ischial Bursitis can be confused with myoxoid tumors. These are a group of rare tumors showing myoxoid change, including neurofibroma, schwannoma and myoxoma. Therefore it may be necessary to do an incisional or excisional biopsy.[8] By using this technique the doctors take cells out of the injured place and they can histologically differentiate cells from a myoxoid tumor or from Ischial Bursitis. An X-ray also rules out the possibility of a stress fracture or roughening of the cartilage in the hip joint.[6]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- MRI: T1 weighted scans show an injury with intermediate intensity[3] [8]. T2 weighted scans show a higher intensity of this lesion, suggesting a space filled with fluid.

- X-Ray[11]

Examination[edit | edit source]

- Pain with straight leg raise test is often present.[9][6][8]

- Active resisted extension of the affected hip reproduces the pain.[9]

- Plain radiographs may reveal calcification of the bursa and associated structures which is consistent with chronic inflammation.[9]

- Examination of patients with ischial bursitis reveals a soft tissue mass in the gluteal region of the affected hip. This soft tissue mass is described as well defined, non-mobile and slightly tender.[3][8]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

A combination of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and physical therapy. Steroid injections are reserved for patients who do not respond to analgesics. [9]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

- Rest: The treatment begins with rest. Rest in the meaning of keep on doing your daily activities and sporting but at a lower intensity. The recommendation is to stay within your pain threshold.

- Cold therapy: Cold therapy contains ice application with cold packs usually for about 20-30 minutes.[12]. This application of cold leads to lowering of the temperature of the skin, subcutaneous tissues and to a lesser degree, deeper tissues like muscle, bone and joint. Cold water, cold gel packs and ethyl chloride or other sprays can be used, depending on the clinical situation.[13]

- Ultrasound therapy[14][15]

- Heat treatment is also possible, with hot packs. It increases blood flow and oxygen tension. The treatment is used twice a day for 30 minutes. Target temperatures range from approximately 38°C to 50°C.[16]

- Frictional massage: It is recommended to use friction massage additional to the therapy on chronic bursitis because it affects the adhesions in chronic bursal problems.[17] It breaks down scar tissue, increases extensibility and mobility of the structure, promotes normal orientation of collagen fibers, increases blood flow, reduces stress levels, and allows healing to take place. Friction massage is beneficial to the underlying structures. [18]By using the Graston technique of friction massage the patient should be forewarned because it may initially aggravate a chronic subacute inflammation that is present. It is postulated that deep friction, especially with the Graston technique instruments, may initiate a new inflammatory cascade, which is necessary to reach the remodelling stage of the inflammatory process and result in healing of the area.[19]

- Therapeutic exercises: should contain stretching exercises to increase the flexibility of tight hamstrings muscle and reducing pressure on the bursa and achieving painless motion and strengthening exercises, to correct muscle imbalances, ease symptoms.[1][20][21] Static stretching is believed to be the safest method because it would have the lowest injury risk. It is most effective when you stretch once a day, 30 seconds for each stretch. [22][23] The benefits of static stretching includes preventing the tissue from absorbing great amounts of energy per unit time, doesn't elicit a forceful reflex contraction and it is good against muscle soreness. [22]

Examples of static stretching exercises: [1]

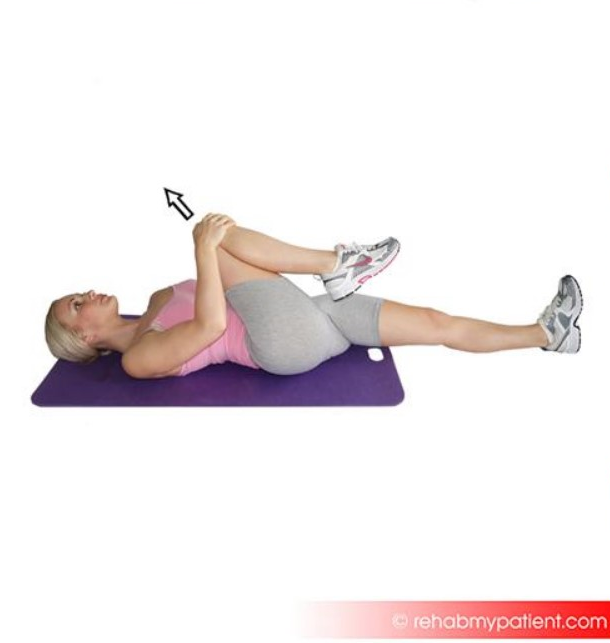

- Gluteus stretch:

Lie on your back and bend your affected knee upward. Grab the back of your knee with both hands and slowly pull the knee toward your chest. Hold this position for 5 to 10 seconds and repeat 6 to 10 times.

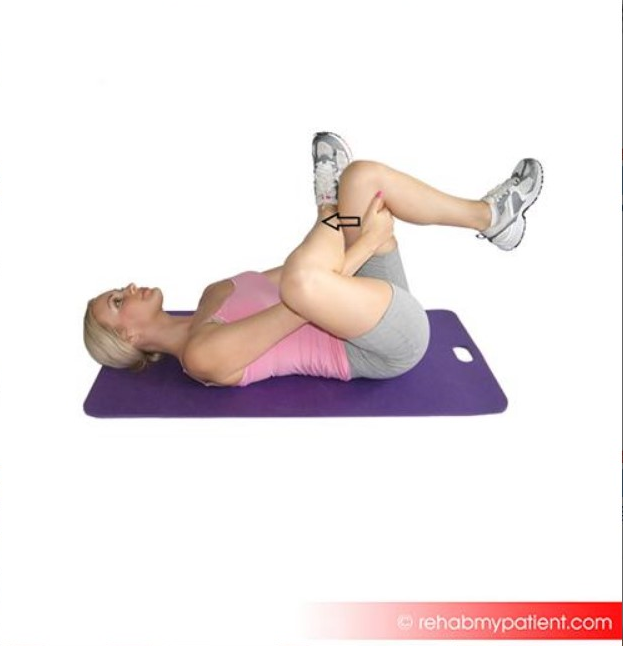

- Piriformis stretch:

While lying on the floor, bend your affected knee and cross the leg over the other leg, placing your foot alongside the knee. Use your hands to pull the good leg in towards you, lifting the leg off the floor. You should feel a stretch in the affected buttock and in your outer thigh. Hold this position for 10-30 seconds.

- Strengthening of the hip rotators is a frequently used rehabilitation program.[7]

- Another program contains strengthening of the hamstrings and gluteal muscles by climbing stairs and reverse curls.[24]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Johnson DB, Varacallo M. Ischial Bursitis. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Mar 19. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kim, S., & al., et al., (2002). Imaging features of ischial bursitis with an emphasis on ultrasonography. Skeletal Radiol , pp. 631-636.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Van Mieghem, I. M., & al., et al. (2004). Ischiogluteal bursitis: an uncommon type of bursitis. Skeletal Radiol , pp. 413-416.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Cho, K.-h., et al. (2004, November 13). Non-infectious ischiogluteal bursitis: MRI findings. Korean J Radiol , 208-286.

- ↑ Zimmermann III, B., et al. (1995). Septic Bursitis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism , 391-410.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Weiss, L., & al, et al. (2007). Ischial Bursa. In Easy Injections (pp. 92-94). Philadelphia: Elsevier.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Paluska, S. A. (2005). An overview of Hip Injuries in Running. Sport Medicine , pp. 991-1014.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Hitora, T., & al, et al. (2008). Ischiogluteal bursitis: a report of three cases with MR findings. Rheumatol Int , 455-458.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Waldman, S. D. (2012). Ischial Bursitis. In Atlas Of Common Pain Syndromes (pp. 288-290). Philadephia: Elsevier Saunders.

- ↑ Pécina, M. M., & Bojanic, I. (2004). Bursitis. In Overuse injuries of the musculoskeletal system (pp. 305-313). Florida: CRC Press.

- ↑ Ryan, A. J. (1962). Bursitis. In Medical care of the athlete (p. 132). McGraw hill.

- ↑ Cuccurullo, S. (2004). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Board Review. New York.

- ↑ Ernst, E., & Fialka, V. (1994, January 1). Ice Freezes pain? A review of the clinical effectiveness of analgesic cold therapy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management , pp. 56-59.

- ↑ Swam Downing, D., & Weinstein, A. (1986, February). Ultrasound Therapy of Subacromial Bursitis. Physical Therapy. Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association , pp. 194-199.

- ↑ Luck J., L. (n.d.). Musculoskeletal Ultrasound Intervention: Principles and Advances. p. 515-533.

- ↑ Badgwell Doherty, C. (2009). Thermotherapy in dermatologic infections. Continuing medical education , 909-927.

- ↑ Hammer, W. (1993). The use of transverse friction massage in the management of chronic bursitis of the hip and shoulder. Journal of Manipulative & physiological therapeutics

- ↑ Premkumar, K. (2004). The massage connection: anatomy and physiology.

- ↑ Hammer, W. I. (2007). Hip Bursitis. In Functional Soft-Tissue Examination and Treatment by Manual Methods (P. 281). Jones and Bartlett Publishers Inc.

- ↑ Thacker, S. B., et al. (2004). The impact of stretching on sports injury risk: a systematic review of the literature. Official journal of the American College of sports medicine , 371-378.

- ↑ Pécina, M. M., & Bojanic, I. (2004). Bursitis. In Overuse injuries of the musculoskeletal system (pp. 305-313). Florida: CRC Press.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Brady, W. D., et al. (1998). The effect of static stretch and dynamic range of motion training on the flexibility of the hamstrings muscles. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sporrts Physical Therapy , 295-300.

- ↑ Bandy, W. D. (1997). The effect of time and frequency of static stretching on flexibility of the hamstrings muscles. Physical therapy , 1090-1096.

- ↑ Subotnic, S. (1991). In Conventional, Homeopathic & alternative treatments. Sport & Exercise injuries. (p. 279). California: North Atlantic Books.