International Framework for Examination of the Cervical Region

This article is currently under review and may not be up to date. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (6/02/2023)

Original Editor - Lucy Aird

Top Contributors - Tarina van der Stockt, Aya Alhindi, Lucy Aird, Ewa Jaraczewska, Admin, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Simisola Ajeyalemi and Claire Knott

Background[edit | edit source]

This page is based on the following:

Rushton A, Carlesso L, Flynn T, Hing W, Rubinstein S ,Vogel S, Kerry R. International Framework for Examination of the Cervical Region for Potential of Vascular Pathologies of the Neck Prior to Musculoskeletal Intervention: International IFOMPT Cervical Framework. International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists (IFOMPT). 2023[1]

This position statement, based on the International IFOMPT (International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists) Cervical Framework, was developed to assist clinicians during their clinical reasoning process when considering presentations involving the head and neck. It has moved from the IFOMPT language of “OMT” (orthopaedic manual therapy) to musculoskeletal intervention.This change was to ensure clarity for all clinicians and that the revised framework completes a planned update of the original (2012) framework to ensure access to the contemporary evidence for clinical reasoning.The International IFOMPT Cervical Framework, developed through rigorous consensus methods, guides assessment of the cervical spine region for potential vascular pathologies of the neck prior to planned interventions. Events and manifestations of vascular pathologies of the neck are uncommon within the cervical spine, but they must be considered as part of the patient examination. Vascular pathologies may be detectable if the appropriate questions are asked during the patient history-taking process, if the interpretation of elicited data allows recognition of this potential, and if the physical examination can be adapted to evaluate any potential vasculogenic hypothesis.[2]The document was published in 2012 as a resource for clinicians. It was scheduled for revision in 2017, and the final revision was published in September 2020.The revised 2020 framework is free on the IFOMPT website. As a consensus document, the Framework was developed through rigorous methods and pivots around clinical reasoning and evidence-based practice.

IFOMPT[edit | edit source]

Please visit www.ifompt.org for all information.

The vision statement of IFOMPT is as follows:

"World-wide promotion of excellence and unity in clinical and academic standards for manual/musculoskeletal physiotherapists."

The vision statement summarises the mission of IFOMPT that, as an organisation, it aims to:

- Promote and maintain high standards of specialist education and clinical practice in manual/musculoskeletal physiotherapists.

- Promote and facilitate evidence-based practice and research amongst its members.

- Communicate widely the purpose and level of the specialisation of manual/musculoskeletal physiotherapists amongst physiotherapists, other healthcare disciplines and the general public.

- Work towards international unity/conformity of educational standards of practice amongst manual/musculoskeletal physiotherapists.

- Communicate and collaborate effectively with individuals within the organisation and with other organisations.

The Standards Committee of IFOMPT is a sub-committee of the Executive Committee and is responsible for advising the Executive on educational issues and maintaining standards. The Standards Document is the guideline document that IFOMPT provides for groups of Manual Therapists who wish to seek membership in IFOMPT through the creation of postgraduate educational programmes in Orthopaedic Manual Therapy (OMT). Part A of the Standards Document[3]details the educational standards.

Consensus Methodology[edit | edit source]

The framework was developed through rigorous methods and is not intended to be a set of systematic reviews aimed at answering specific questions. The consensus process looked at the breadth and complexity of evidence, clinical reasoning, and facilitated recommendations where there was a lack of published material and significant uncertainty.

Precisely defined substantive areas were identified for each section of the framework, and relevant electronic databases, reference lists, key journals, existing networks, and relevant organizations and conferences were searched. Within each section, study selection and data and information charting were carried out in accordance with its focus. There were 4 stages to developing the framework:

- Stage 1:

A survey to evaluate the previous 2012 cervical framework was distributed to all member organizations and registered interest groups of IFOMPT in 2016.

- Stage 2:

The key issues identified in the survey were initially explored at the IFOMPT Conference in 2016 in Glasgow. Findings from the evaluation survey were presented to facilitate discussion and debate through platform presentations. Which confirmed the need for an updated version of the framework.

- Stage 3:

Drafts of the framework were developed through an iterative consultative process and distributed for review and feedback to IFOMPT member organizations and registered interest groups, international experts/authors, nominated experts within IFOMPT countries, and professional organizations across physical therapy, osteopathy, and chiropractic.

- Stage 4:

The framework was voted on and accepted unanimously at the IFOMPT General Meeting in November 2020 by 22 member organizations (countries) as an international position statement for musculoskeletal clinicians.

Reason for the Development of the Framework[edit | edit source]

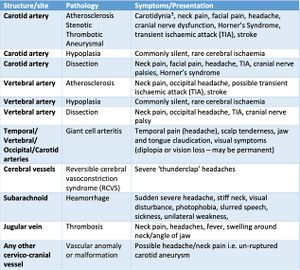

Although vascular pathologies of the neck and head are uncommon, they are an important consideration for clinicians treating patients with neck and/or head pain. Identifying vascular pathologies in this region is a challenging task. The arterial system, which supplies blood to the brain, can have a variety of vascular pathologies and dysfunctions. They are important for physiotherapists/physical therapist who treat musculoskeletal conditions in two ways:

- Neurovascular incidents have been associated with therapeutic interventions.

- There exist multiple arterial pathologies (vascular masqueraders) which could present as musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction of the neck, like neck pain and headache.

The International IFOMPT Cervical Framework aims to increase the physiotherapists' understanding of risk and pathology to promote patient safety and can help health care professionals working with cervical musculoskeletal conditions by promoting early detection of vascular pathologies, resulting in the best possible outcome for patients. It is based on the most recent evidence and expert opinion to help all clinicians with their clinical reasoning.

Aim of the framework[edit | edit source]

- The framework is designed to guide the assessment of the cervical spine region for the potential of vascular pathologies in the neck in advance of planned OMT interventions. The IFOMPT definition of Orthopaedic Manual Therapy (OMT), voted in at the General Meeting in Cape Town March 2004, is:

OMT is a specialised area of physiotherapy/physical therapy for the management of neuro-musculo-skeletal conditions, based on clinical reasoning, using highly specific treatment approaches including manual techniques and therapeutic exercises.

OMT also encompasses, and is driven by, the available scientific and clinical evidence and the biopsychosocial framework of each individual patient.

- OMT interventions for the cervical spine addressed through this framework include manipulation, mobilisation and exercise. Attention is focused on techniques in end-range positions of the cervical spine during mobilisation, manipulation and exercise interventions.

- The framework is based on the best available evidence at the time of writing. It is designed to be used with the IFOMPT Standards[3] that define postgraduate best practices in OMT internationally. Central to this framework is sound clinical reasoning and evidence-based practice.

- Within the cervical spine, events and presentations of vascular pathologies of the neck are rare but are an essential consideration as part of an OMT assessment. Arterial dissection (a tear in the lining of an artery) and other vascular presentations are somewhat recognisable if the appropriate questions are asked during the patient history, if the interpretation of elicited data enables the recognition of this potential, and if the physical examination can be adapted to explore any potential vasculogenic hypothesis further. Therefore, the framework reflects best practices and aims to place risk in an appropriate context informed by the evidence. In this context, the framework considers ischaemic and non-ischaemic presentations to identify risk before overt symptoms in a patient presenting for cervical management.

- An important underlying principle of the framework is that physical therapists cannot rely on the results of only one test to conclude. Therefore, developing an understanding of the patient’s presentation following an informed, planned, and individualised assessment is essential. Multiple sources of information are available from the patient assessment process to improve confidence in estimating the probability of vascular pathologies of the neck. Data available to inform clinical reasoning will improve and change with ongoing research. This framework, therefore, encourages physical therapists to critically read the current literature to enable support for their clinical decisions rather than provide specific data prescriptive guidance, as the evidence base for this is not available.

- The framework is intended to be informative and not prescriptive and aims to enhance the physical therapist’s clinical reasoning as part of the patient assessment and treatment process. The framework is intended as simple and flexible. The physical therapist should be able to apply it to their patients, facilitating patient-centred practice.

IFOMPT Cervical Framework[edit | edit source]

The framework is divided into different sections and is designed to be used in conjunction with crucial literature sources identified in the context section.

[edit | edit source]

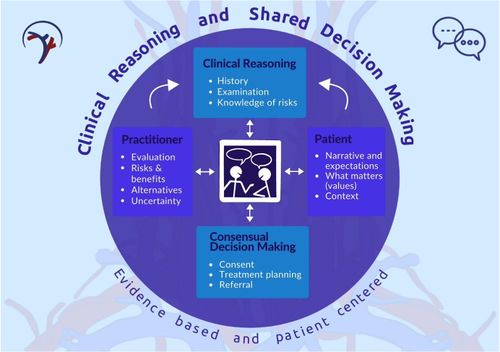

The current framework builds on the previous 2012 framework (first version) and addresses concerns raised by the consensus methodology and empirical work. To enable effective, efficient, and safe assessment and management of the cervical spine region sound clinical reasoning is required.

Shared decision-making is an effective means for reaching agreement on the best strategy for treatment and it fosters patient centered “care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values” and ensures “that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”

The Informed Medical Decision-Making Foundation describes shared decision making as a dynamic two-way process:

- The clinician communicates personalized information about the options, outcomes, probabilities, and scientific uncertainties of available treatment options to the patient.

- The patient communicates their values and the relative importance they place on benefits and harms.

The framework adopts the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s 5-step SHARE approach:

- Seek your patient’s participation.

- Help your patient explore and compare treatment options.

- Assess your patient’s values and preferences.

- Reach a decision with your Patient.

- Evaluate your patient’s decision, to achieve patient-centered practice.

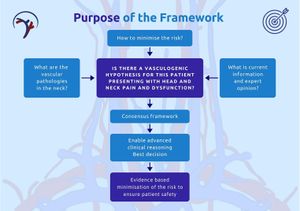

Section 2: Purpose of the Framework[edit | edit source]

- In advance of planned interventions such as mobilisation, manipulation, and exercise, the IFOMPT cervical framework guides assessment of the cervical spine region for potential vascular pathologies of the neck.

- Events and manifestations of vascular pathologies of the neck are uncommon within the cervical spine, but they must be considered as part of the patient examination.

- Vascular pathologies may be detectable if:

- the appropriate questions are asked during the patient history-taking process.

- the interpretation of elicited data allows recognition of this potential.

- the physical examination can be adapted to investigate any potential vasculogenic hypothesis.

- The framework is based on best practises and aims to place risk in a context informed by evidence. The framework considers ischaemic and nonischaemic presentations in this context to identify risk in a patient presenting for cervical examination and management.

- One of the IFOMPT cervical framework's goals is to ensure that clinicians understand risk in both epidemiological and individual contexts as clinicians cannot draw conclusions based on the results of a single test. Understanding the patient's presentation after an informed, planned, and individualised evaluation is critical.

Epidemiologically, the risk of a vascular incident related to therapeutic interventions is extremely low. Regardless, clinicians must do everything possible to mitigate and limit that risk.

Individually, patients differ in terms of risk , hazard , profile , or the presence of vascular pathology.

Stages of the clinical reasoning process[edit | edit source]

- Taking a patient’s history.

- Planning the physical examination.

- Conducting the physical examination.

- Planning the intervention.

- Evaluating the intervention.

Case 1 :[edit | edit source]

History:

50-year-old male brick layer complains of a headache. His headache is similar but different to previous migraine headaches that he intermittently experiences. This is different in that he also feels lethargic and “run down.” With this in mind, he decides to go to bed sure that he will feel better in the morning as he does feel fatigued and “sleepy.” Upon waking, his headache is still present. He thinks that he needs to exercise and “get out for some fresh air” (similar to previous headaches) so he walks to the shops to get some essentials. The checkout operator says that she cannot understand what he is saying and that his speech is slurred. He is confused as he knows what he is saying and feels this is due to his “over-doing it.” He reflects and cannot understand why he is still lethargic and cannot concentrate on things. Upon his wife arriving home from work, she also comments that he is difficult to understand and that he needs to concentrate on their conversation as “he is he not listening to her.” She calls a physical therapist friend to seek advice.

Synopsis:

A headache described as “unusual” with progressive signs of likely central ischemia (slurred speech, lethargy, fatigue, confusion) is sufficient information for the therapist to recommend emergency medical attention.

Section 3: Patient history[edit | edit source]

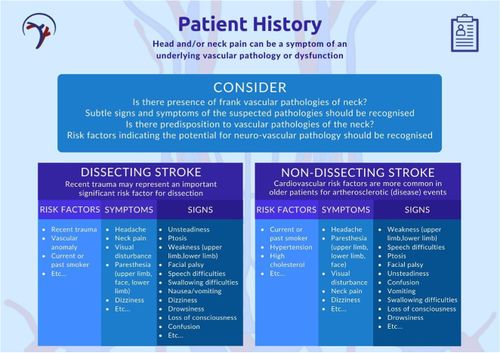

The patient history is used to develop and test hypotheses about the risk of vascular pathologies in the neck or the presence of frank vascular pathologies . Physical examination tests have very limited diagnostic utility data. As a result, the clinician's goal is to use the patient history to make the best judgement on the possibility of treatment contraindications or serious pathology. Subtle signs and symptoms of suspected pathologies should be identified during the patient history taking process. It is also critical to recognise risk factors that indicate the possibility of neurovascular pathology.

Considering Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

A vascular pathology of the neck event has a complex and multifactorial etiology.Several factors have been linked to an increased risk of arterial pathologies involving the internal carotid or vertebrobasilar vessels. These should be thoroughly considered while taking a patient's history.

Check the tables on page 11 for detail risk factors for dissection and non-dissection vascular events (combining vertebrobasilar artery [VBA] and internal carotid artery [ICA] pathologies).

It is critical to recognise clinical pattern elements that may support or disprove a vascular hypothesis. A definite clinical pattern cannot be identified due to the extremely low prevalence, wide range of pathologies, and high variation of the presenting features of vascular pathologies of the neck. However, certain consistent features of clinical presentation emerge from historical case reports, which are supported by observations from systematic reviews.

Importance of Observation Throughout History[edit | edit source]

While the clinician is taking the patient's history, signs and symptoms of serious pathology, as well as contraindications/precautions to treatment, may manifest. This is a chance to observe and identify potential red flag indicators early in the clinical encounter such as:

- Gait disturbances.

- Subtle signs of disequilibrium.

- Upper motor neuron signs.

- Cranial nerve dysfunction.

- Behavior suggestive of upper cervical instability (eg, anxiety, supporting head/neck.)

Case 2 :[edit | edit source]

History:

A 46-year-old female supermarket worker presents for physical therapy with left-sided head (occipital) and neck pain described as “unusual.” She reports a 10-day history of the symptoms following a road traffic accident. The symptoms are progressively worsening. The pain is eased by rest. The patient reports an onset of new symptoms after about 7 days, including “feels like might be sick,” “throaty,” and “feels faint”—especially after performing gentle exercise. Two days after this, she reports a stronger feeling of nausea, loss of balance, swallowing difficulties, speech difficulties, and acute loss of memory. She reports a history of previous road traffic accidents. Past medical history included hypertension, headaches, high cholesterol, and a maternal family history of heart disease and stroke.

Synopsis:

Progressive “unusual” headache with emerging hindbrain/central neurology with history of trauma indicates additional testing to support a medical referral.

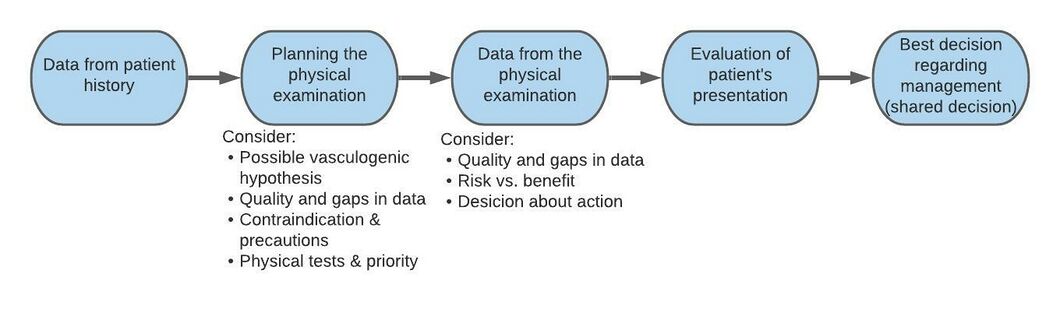

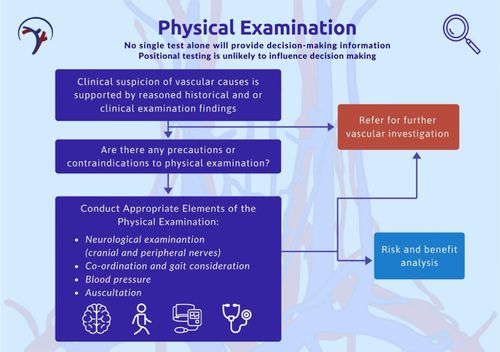

Section 4: Planning the physical examination[edit | edit source]

Necessity for planning[edit | edit source]

A process of interpreting the data from the patient history and defining the main hypotheses is essential to an effective physical examination[4][5]. Hypothesis generation from the history and refining, re-ranking and rejecting of these hypotheses in the physical examination is necessary to facilitate optimal clinical reasoning in OMT[6]. Therefore careful planning of the physical examination is required. In particular, for this framework, the possible vasculogenic (cervical arterial) contribution to the patient’s presentation needs to be evaluated from the patient history data.

Are any further patient history data required?[edit | edit source]

An important component of planning is identifying any further patient history data that may be required. That is, are there any gaps in the information obtained? Is the quality of the information obtained sufficient?

Decision-making regarding the physical examination[edit | edit source]

Based upon the evaluation and interpretation of the data from the patient history, the physical therapist needs to decide the following:

- Are there any precautions for OMT?

- Are there any contraindications to OMT?

- What physical tests need to be included in the physical examination?

- What is the priority for these physical tests for this specific patient? This is to inform decisions regarding the testing order and determine which tests should be completed at the first visit.

- Do the physical tests need to be adapted for this specific patient?

Section 5: Physical examination[edit | edit source]

The purpose of the physical examination is to continue to test the vascular hypothesis generated during the history.

Hypertension strongly predicts cardiovascular disease[7], but it should be interpreted in the context of other findings with sound clinical reasoning. Hypertension and neck pain are only two factors influencing the decision on the probability of vascular pathology.

Neurological examination

Neurological examination for musculoskeletal clinicians is a key element for safe clinical practice. It allows to identification of upper and/or lower limb and upper motor neuron pathology. [8] Examination of the peripheral nerves and cranial nerves in assessing for an upper motor neuron lesion will assist in evaluating the potential for neurovascular conditions. Follow this link to learn more about testing. An increasing body of literature details clinical cases of arterial pathology with cranial nerve involvement to inform pattern recognition. The absence of findings does not rule out underlying pathology.

Read the guide to cranial nerve testing for musculoskeletal clinicians here.

Examination of the carotid artery

The physiotherapist should aim to understand and experience both normal and pathological pulse quality. Auscultation is advised as palpation of the internal carotid artery may induce vagal reactions (especially when palpating bilaterally). In most cases, the sensitivity or specificity of pulse examination is unknown. Still, in the correct clinical context, it may offer important evidence leading to specific diagnoses and treatment[9].

- An alteration of the internal carotid artery pulse has been identified as a feature of the internal carotid disease [10]

- Asymmetry between left and right vessels is considered significant

- A pulsatile, expandable mass indicates an arterial aneurysm[11]

- A bruit on auscultation (controlling for normal turbulence) indicates a significant finding and should be considered in the context of other clinical findings.

Differentiation during the physical examination

Differentiation of a patient’s symptoms originating from a vasculogenic cause with complete certainty is not currently possible from the physical examination. Thus, it is important for the physical therapist to understand that headache/neck pain may be the early presentation of an underlying vascular pathology[12][13]. The task for the therapist is to differentiate the symptoms by:

- Having a high index of suspicion

- Testing the vascular hypothesis.

This process of differentiation should take place from an early point in the assessment process, i.e. early in the patient history. The symptomology and history of a patient experiencing vascular pathology are what may alert the physical therapist to such an underlying problem[12][13]. A high index of suspicion of cervical vascular involvement is required in cases of acute onset neck/head pain described as “unlike any other”[13]. Physical therapists may be exposed to patients presenting with the early signs of stroke (for example, neck pain/headache) and need both knowledge and awareness of the mechanisms involved. A basic understanding of vascular anatomy, haemodynamics and the pathogenesis of arterial dysfunction may help the physical therapist differentiate vascular head and neck pain from a musculoskeletal cause[12][13] through interpretation of the patient history data and tests in the physical examination.

Refer on for further investigation

- There exist no clinical guidelines for medical diagnostic work-up regarding vascular pathology.

- The physiotherapist should follow local policy in referring for further investigation. Immediate referral for medical investigation should occur with clinical suspicion of vascular pathology.

- Conventionally, duplex ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging/arteriography, and computed tomography are used in the workup.

Additional training

Physiotherapists should receive additional training if their current OMT practice does not include the tests mentioned in this Framework.

Section 6 Risk and benefit[edit | edit source]

Framework for evaluating risk

This section relates to those patients NOT presenting with a discrete vascular pathology but instead with neuromusculoskeletal craniocervical dysfunction suitable for OMT mobilisation, manipulation and exercises intervention. This assessment of risk and benefit relates to the risk associated with treatment, not misdiagnosis.

In the context of this Framework, there are two substantive but related risks:

- The risk of misdiagnosis of an existing vascular pathology

- The risk of serious adverse events following OMT

For instance, a patient presents with neck pain / headache but develops a severe adverse event, such as a dissection due to underlying pathology aggravated by treatment)

Risk

See the Risk and Benefit diagram to the right.

Benefit

The benefits of OMT are reported in high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses by different authors[14][15][16][17]. OMT and exercise interventions are also included in the most recent Clinical Practice Guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health[18]. The combination of OMT and exercise for neck pain and associated disorders like headache and radiculopathy have been proven effective[19][20].

Person-centred decision-making

From an individual level, based on the background literature, which highlights various risk factors for specific pathologies in specific people, the epidemiological data must be contextualised in the particular patient encounter. This is also the case for decision-making regarding the choice of intervention and its predicted benefit. Accurate data to inform a precise level of risk at an individual level is lacking, so it is not possible to develop valid clinical prediction rules for risk or benefit. Absolute risk judgement cannot be made by the physiotherapist, and the therapist must accept that the clinical decision is made without certainty and a decision based on a balance of probabilities. When in doubt, consider not intervening, and assess the chance of recovery of pain and dysfunction (assuming a musculoskeletal dysfunction).

See page 25 of the Framework for a clinical reasoning flowchart for risk assessment before cervical manual therapy.

[edit | edit source]

Shared decision-making covers the professional and ethical obligations of informed consent. Still, it surpasses informed consent by recognising the patients’ rights to make decisions about their care, ensuring they are adequately informed about treatment options and their consequences, providing patients with sufficient opportunities to discuss them and by jointly agreeing on a course of action for each individual (Moulton et al., 2013)[21]. The specific requirements of informed consent will vary from country to country according to local laws, regulatory expectations, customs and norms.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has proposed 5 steps based on the SHARE approach that will help facilitate the process of shared decision-making with your patients. Follow this link if you want to learn more about this.

Further information on consent is provided in pages 27 and 28 of the Framework

Section 8: Safe OMT practice[edit | edit source]

You will find more information on this section on the related page: Section 9: Safe OMT practice, including emergency management of an adverse situation

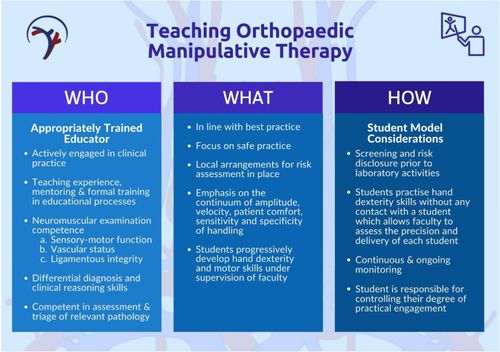

Section 9: Teaching OMT for the cervical region[edit | edit source]

You will find more information on this section on the related page: Section 10: Teaching OMT for the Cervical Region

Additional Outcome Measurement[edit | edit source]

In 2017, the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association published a revised Clinical Practice Guidelines related to neck pain. They include updated recommendations for outcome measurement tools that clinicians can use for evaluation, prognosis and diagnosis of neck pain. [22]These recommendations include the following:

- The Neck Disability Index (NDI)

- Patient Specific Functional Scale [23]

- SF-36

- Medical Outcomes Study 12-Items Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12)

NDI, The Bournemouth Questionnaire, and the Neck Pain and Disability Questionnaire [24] include items across the ICF components.[22]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Rushton A, Rivett D, Carlesso L, Flynn T, Hing W, Rubinstein S ,Vogel S, Kerry R.https://www.jospt.org/doi/epdf/10.2519/jospt.2022.11147 International IFOMPT Cervical Framework. International Federation of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists (IFOMPT). 2023

- ↑ J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2023;53(1):7–22. Epub: 14 September 2022. doi:10.2519/jospt.2022.11147

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 IFOMPT (2008). IFOMT Educational Standards Document. Available at: http://www.ifompt.com/Standards/Standards+Document.html Accessed December 2012

- ↑ Maitland G, Hengeveld E, Banks K, et al (Eds)(2005). Maitland's Vertebral Manipulation, 7th Edn, Elsevier Butterworth Heinneman, Edinburgh.

- ↑ Petty NJ (2011). Neuromusculoskeletal Examination and Assessment: A Handbook for Therapists (Physiotherapy Essentials), 4th edn, Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, Edinburgh.

- ↑ Jones MA, Rivett DA (2004). Introduction to clinical reasoning. In M.A. Jones and D.A. Rivett (eds.), Clinical Reasoning for Manual Therapists. Butterworth-Heinemann: Edinburgh 3-24.

- ↑ Saiz, L.C., Gorricho, J., Garjón, J. (2017). Blood pressure targets for treating people with hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10, CD010315.

- ↑ Taylor A, Mourad F, Kerry R, Hutting N. A guide to cranial nerve testing for musculoskeletal clinicians. J Man Manip Ther. 2021 Dec;29(6):376-389.

- ↑ Pickett, C.A., Jackson, J.L., Hemann, B.A., Atwood, J.E. (2011). Carotid artery examination, an important tool in patient evaluation. Southern Medical Journal, 104(7), 526-532.

- ↑ Patel, R.R., Adam, R., Maldjian, C., Lincoln, C.M., Yuen, A., Arneja, A. (2012). Cervical carotid artery dissection: current review of diagnosis and treatment. Cardiology in Review, 20(3), 145-152. 38 |

- ↑ Elder, A., Japp, A., Verghese, A. (2016). How valuable is a physical examination of the cardiovascular system? British Medical Journal, 354, i3309.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Rivett DA (2004). Adverse effects of cervical manipulative therapy. In J.D. Boyling and G.A. Jull (eds.), Grieve’s Modern Manual Therapy of the Vertebral Column (3rd ed). Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh 533-549.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Taylor AJ, Kerry R (2010). A ‘system based’ approach to risk assessment of the cervical spine before manual therapy. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine 13:85-93

- ↑ Gross, A., Langevin, P., Burnie, S.J. et al. (2015). Manipulation and mobilisation for neck pain contrasted against an inactive control or another active treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 23(9), CD004249.

- ↑ Lozano López, C., Mesa Jiménez, J., de la Hoz Aizpurúa, J.L. (2016). Efficacy of manual therapy in treating tension-type headache: A systematic review from 2000-2013. Neurologia, 31(6), 357-69.

- ↑ Zhu, L., Wei, X., Wang, S. (2016). Does cervical spine manipulation reduce pain in people with degenerative cervical radiculopathy? A systematic review of the evidence, and a meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30(2), 145-155.

- ↑ Varatharajan, S., Ferguson, B., Chrobak, K., et al. (2016). Are non-invasive interventions effective for the management of headaches associated with neck pain? An update of the Bone and Joint Decade Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. European Spine Journal, 25(7), 1971-1999.

- ↑ Blanpied, P.R., Gross, A.R., Elliott, J.M., Devaney, L.L., Clewley, D., Walton, D.M., Sparks, C., Robertson, E.K. (2017). Neck pain: Revision 2017. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 47(7), A1-A83.

- ↑ Hidalgo, B., Hall, T., Bossert, J., Dugeny, A., Cagnie, B., Pitance, L. (2017). The efficacy of manual therapy and exercise for treating non-specific neck pain: A systematic review. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, 30(6), 1149-1169.

- ↑ Fredin, K., Lorås, H. (2017). Manual therapy, exercise therapy or combined treatment in managing adult neck pain - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 31, 62-71

- ↑ Moulton, B., Collins, P.A., Burns-Cox, N., Coulter, A. (2013). From informed consent to informed request: do we need a new gold standard? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 106(10), 391-394.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, Devaney LL, Clewley D, Walton DM, Sparks C, Robertson EK. Neck Pain: Revision 2017. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Jul;47(7):A1-A83.

- ↑ Thoomes-de Graaf M, Fernández-De-Las-Peñas C, Cleland JA. The content and construct validity of the modified patient-specific functional scale (PSFS 2.0) in individuals with neck pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2020 Feb;28(1):49-59.

- ↑ Yao M, Xu BP, Tian ZR, Ye J, Zhang Y, Wang YJ, Cui XJ. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Neck Pain and Disability Scale: a methodological systematic review. Spine J. 2019 Jun;19(6):1057-1066.