Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: Difference between revisions

(content updated - general saving done) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Description == | == Description == | ||

[[File:3D model expressing hip pain.jpg|thumb]] | [[File:3D model expressing hip pain.jpg|thumb]] | ||

Greater | Lateral hip pain previously used to be referred to as trochanteric bursitis but this has been replaced by Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS). GTPS is a clinical diagnosis of lateral hip pain and includes trochanteric bursitis associated with a tendinopathy<sup>3,4,8</sup>, gluteus medius (GMed) and minimus (GMin) tendinopathy<sup>1,8,10,23</sup>, tears of the GMed and GMin tendons<sup>1,8</sup> and external coxa saltans (snapping hip syndrome).<sup>1,10</sup> Iliotibial band (ITB) abnormalities are also a possible cause of GTPS.<sup>3</sup> Fearon et al. (2012) proposed a clinical definition of GTPS: “a history of lateral hip pain and no difficulty with manipulating shoes and socks together with clinical findings of pain reproduction on palpation of the greater trochanter and lateral pain reproduction with the FABER test.”<sup>20</sup> This was proposed as the authors found that being able to manipulate socks and shoes without pain differentiates GTPS from hip osteoarthritis (OA) and a positive FABER is sensitive and specific for GTPS.<sup>20</sup> | ||

Previously, trochanteric bursitis was seen as the main pain source, but recent research indicates that the fluid within the bursa rather exists due to the gluteal tendinopathy and not because of primary inflammation in the bursa.<sup>3,4,9</sup>. The most recent research indicates GMed and GMin tendinopathy as the most frequent cause of GTPS<sup>7,9,12,13,42,23</sup> and managing the underlying tendinopathy should take priority.<sup>8</sup> GTPS is more common in females (outnumbering men by between 2.4 – 4: 1<sup>7</sup>) between the ages of 40 and 60<sup>4,1,13</sup> and accounts for 10 – 20% of patients presenting with hip pain in primary care. It has an incidence between 1.8 and 5.6 per 1000 per year. <sup>43, 4, 11,1</sup> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy== | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy== | ||

| Line 135: | Line 137: | ||

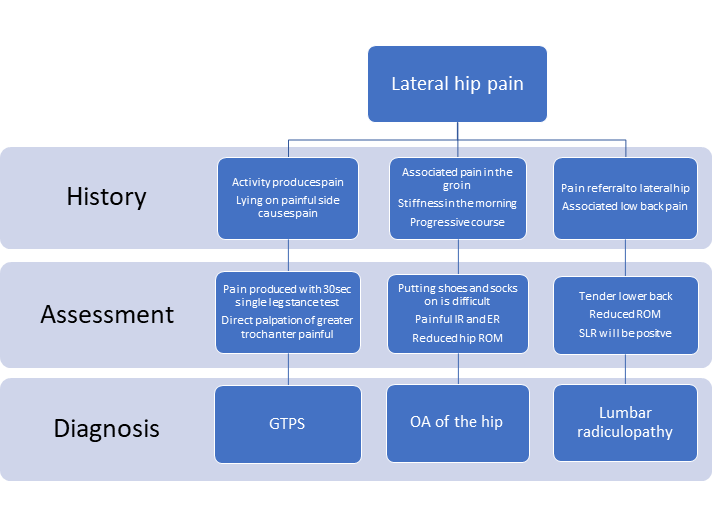

Below is a diagnostic flow chart created by Speers and Bhogal (2017) for the 3 most common causes of lateral hip pain.<sup>4</sup> | Below is a diagnostic flow chart created by Speers and Bhogal (2017) for the 3 most common causes of lateral hip pain.<sup>4</sup> | ||

[[File:Common causes of lateral hip pain.png|left|thumb|712x712px|Common causes of lateral hip pain]] | [[File:Common causes of lateral hip pain.png|left|thumb|712x712px|Common causes of lateral hip pain]] | ||

== Outcome Measures== | == Outcome Measures== | ||

Revision as of 13:37, 15 March 2020

Original Editors - Kirianne Vander Velden

Top Contributors -Wendy Snyders, Kim Jackson, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Ahmed M Diab, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Rishika Babburu, Andrea Nees and WikiSysop

Description[edit | edit source]

Lateral hip pain previously used to be referred to as trochanteric bursitis but this has been replaced by Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS). GTPS is a clinical diagnosis of lateral hip pain and includes trochanteric bursitis associated with a tendinopathy3,4,8, gluteus medius (GMed) and minimus (GMin) tendinopathy1,8,10,23, tears of the GMed and GMin tendons1,8 and external coxa saltans (snapping hip syndrome).1,10 Iliotibial band (ITB) abnormalities are also a possible cause of GTPS.3 Fearon et al. (2012) proposed a clinical definition of GTPS: “a history of lateral hip pain and no difficulty with manipulating shoes and socks together with clinical findings of pain reproduction on palpation of the greater trochanter and lateral pain reproduction with the FABER test.”20 This was proposed as the authors found that being able to manipulate socks and shoes without pain differentiates GTPS from hip osteoarthritis (OA) and a positive FABER is sensitive and specific for GTPS.20

Previously, trochanteric bursitis was seen as the main pain source, but recent research indicates that the fluid within the bursa rather exists due to the gluteal tendinopathy and not because of primary inflammation in the bursa.3,4,9. The most recent research indicates GMed and GMin tendinopathy as the most frequent cause of GTPS7,9,12,13,42,23 and managing the underlying tendinopathy should take priority.8 GTPS is more common in females (outnumbering men by between 2.4 – 4: 17) between the ages of 40 and 604,1,13 and accounts for 10 – 20% of patients presenting with hip pain in primary care. It has an incidence between 1.8 and 5.6 per 1000 per year. 43, 4, 11,1

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

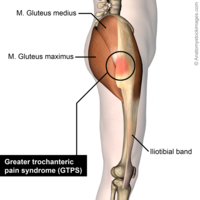

The greater trochanter is situated on the proximolateral side of the femur, just distal to the hip joint and the neck of the femur. The tendons of the GMed, GMin, gluteus maximus (GMax) and the tensor fascia lata (TFL) attach onto this bony outgrowth (apophysis). The greater trochanter is seen to have 4 facets by Pfirrmann et al.14 and the above-mentioned muscle attachments have been equated to the “rotator cuff of the hip”15,23

The external iliac fossa is the origin of the GMed and GMin muscles, with the GMed attaching to the lateral and superolateral facets and the GMin inserting onto the anterior facet. The TFL lies over the GMed and GMin tendons and inserts onto the ITB14.

The greater trochanteric region has a varying number of bursa but has an average of 6 bursae36 Williams and Cohen (2009) report that four bursae are consistently present and that there are multiple secondary bursa.37 Bursae are fluid-filled structures that reduce friction between bones and soft tissues14. The three chief bursae at the hip include the subgluteus maximus, the subgluteus minimus and the subgluteus medius bursa14. These bursae and the periosteum of the greater trochanter are innervated by a small branch of the femoral nerve14,47. The locations of these bursae vary greatly when observed on cadavers - the size, location and number are not consistent.44,45,46

The GMax muscle tensions the ITB via its ITB attachment and assists with improving the hip joint’s passive stability16. The ITB is also tensioned by the vastus lateralis and TFL and limits hip internal rotation and adduction passivley16. The GMed prevents excessive hip adduction and is often seen as the primary stabilizer of the pelvis16.

The hip joint is innervated by rami articulares of the obturator nerve, the femoral nerve and the sciatic nerve[8] and the recently discovered branch of the femoral nerve that supplies the periosteum and bursa of the greater trochanter. This discovery may be useful to improve therapies, such as interventional denervation of the greater trochanter or anatomically guided injections with corticosteroids and local anesthetics.47 The GMed, GMin and TFL are innervated by the superior gluteal nerve while the GMax is innervated by the inferior gluteal nerve.

Aetiology and pathomechanics[edit | edit source]

Since GMed and GMin tendinopathy, tears of the GMed and GMin tendons, external coxa saltans and ITB abnormalities can all be possible causes of GTPS, the aetiology of each of these structures/pathologies need to be considered.

Tendinopathy is a multifaceted problem and the exact mechanism is still not known.1Overuse of tendons1, mechanical overload1,13 and incomplete or failed healing1 have all proposed as possible causes of tendinopathy. Compression of the tendon at the enthesis is another possible cause13 for insertional tendinopathies. A combination of high tensile loads and excessive compression is thought to be most detrimental.13

In people with weak hip abductors, particularly GMed, greater hip adduction is seen causing increased compression of the GMed and GMin tendons at the greater trochanter. With the increased adduction, the ITB exerts higher compressive forces on the gluteal tendons, amplifying the compression.8 Hip positions in higher ranges of flexion may also increase the compression of the GMed and GMin tendons due to increased tension in the ITB, explaining why pain that occurs with prolonged sitting.13

Kummer (1993) found that pelvic control in a single leg stance position was controlled 70% by the abductor muscles and that the ITB tensioners (GMax, TFL and vastus lateralis) then accounted for the remaining 30%14. This is seen as the abductor mechanism. It has also been shown that people with gluteal tendinopathy tend to have GMed and GMin atrophy and TFL hypertrophy. Weakness and/or muscle bulk changes impact the balance of the abductor mechanism and increase the compression of the gluteal tendons.14

It is postulated that women are more prone to GTPS because of pelvic biomechanics, different activity levels in the population and hormonal effects.15 One study found that females have a smaller insertion of the GMed tendon, resulting in a smaller area across which tensile load could be dissipated. It also makes the moment arm shorter, causing reduced mechanical effeciency.8

A previously mentioned, any increased fluid within the bursa is thought to be a consequence of the tendinopathy rather than it being due to inflammation of the bursa. This being said, one smaller study found that there was an increase in substance P within the bursa in patients with GTPS and specifically gluteal tendinopathy indicating that the bursa is a possible source of pain in GPTS.5

Tears of the GMed and GMin tendons are a frequently missed cause of GTPS.22 According to Domb et al. (2010), up to 25% of middle-aged women can have GMed tears, and up to 10% of middle-aged men.22 Tears can be acute but degenerative tears are far more common with the GMed tendon being most frequently affected.22,23 These tears at the GMed tendon insertion can be complete, intrasubstance or partial, with partial tears occurring most frequently.22,23

Coxa saltans or snapping hip syndrome presents in about 5% to 10% of the general population.25 It is either intra-articular or extra-articular25, with the extra-articular presentation being relevant to GTPS. Extra-articular coxa sultans most commonly involves the anterior part of GMax or the posterior ITB snapping over the greater trochanter, causing a catching or sensation of “giving way” and an inflammatory response in the trochanteric bursa.24,25 There is also often an imbalance between TFL and GMax activation in these patients.24 Patients can report a sensation of subluxation and pain is worst with activities such as climbing stairs, hiking and running.25 There are, however, patients who do not experience pain when it snaps.24 Coxa saltans is most commonly found in dancers and professional athletes, but can also occur due to physical trauma.25 Risk factors in athletes include14:

· Running on an asymmetrical surface, cambered road

· Shoe wear

· Incorrect training

There is no clear evidence that a leg length discrepancy has any impact on a person developing GTPS.7, 14

Patients presenting with GTPS often have low back pain1,7,11 or hip joint OA.1 There is also a higher occurrence of GTPS in people with ITB syndrome and knee OA.2,14

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

GTPS typically presents with lateral hip pain that may radiate down the lateral thigh and buttocks and occasionally to the lateral knee. It can be described as aching and intense at times of greater aggravation caused by passive, active and resisted hip abduction and external rotation.46 It is often characterized by the ‘jump’ sign where palpation of the greater trochanter causes the patient to nearly jump off the bed.4

The symptoms include:

- Tender lateral hip when palpated, especially near the greater trochanter14,12,7,23,22

- Pain with side-lying on the problematic side14,12,7,6,

- Pain with weight-bearing activities such as walking, climbing stairs, standing and running14,12,7,4,22,6,19

- Pain may refer to the lateral thigh and knee14,7,4,23

- Pain with prolonged sitting7,6

- Pain with resisted abduction23,22

- Sitting with crossed legs increases pain

- Pain can also occur when lying on the non-painful side if the painful hip falls into adduction

- Pain is usually episodic and will worsen over time with continued aggravation

- Weak hip abductors19.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

To be able to treat GTPS correctly, accurate differential diagnosis is crucial.20 Conditions that may mimic GTPS include the following:

- Hip OA20,19,14,13,7. Similar site of symptoms, aggravated by weight-bearing activity and weakness in hip abductors.19

- Femoral head avascular necrosis (AV)18,14

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)18,14,7

- Lumbar spine referral or degenerative disease18,13,7

- Femoral-head stress fractures14

- Labral tears14,7

- Bony metastasis7

- Neck-of-femur fracure7

- Inflammatory disease such as RA7

| Table 1 | |

| Differential diagnosis | Important signs and symptoms |

| Hip OA, labral tear, AV, FAI | · Pain in 1 or more of the following regions: deep gluteal region, anterior thigh, knee, groin

· Lateral hip, groin pain and/or deep buttock pain with passive hip medial rotation · Hip locking, giving way · Positive FADDIR test · Decreased hip range of motion |

| Lumbar referral | · Dermatome and sclerotome pain pattern will be present, rather than pain over ITB specifically, for example.

· L2, L3 and L5 in particular14 |

| Inflammatory joint disease | · Obvious inflammatory symptoms with stiffness that lasts more than 1 hour

· Symmetrical symptoms · Hand symptoms often involved |

| Neck-of-femur fracture | · Pain around hip joint area and aggravated with weight-bearing activity. |

| Reference: Grimaldi and Fearon (2015). Gluteal tendinopathy: Integrating pathomehanics and clinical features in its management. | |

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

There is no one specific test to confirm GTPS and the tests available lack validity when done in isolation. Diagnostic accuracy can however be improved when a combination of tests is used.4

When using pain provocation tests, the diagnostic value can be improved by the patient reporting pain on the specific site.7

The single leg stance test for 30 seconds has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% and also has a very high sensitivity when pain is produced within 30 seconds of standing on the painful side. 4,14 Grimaldi and Fearon (2015) however suggest that the test be done either to 30 seconds or until symptom production, whichever comes first.7

Resisted hip medial rotation, lateral rotation and abduction can also be used to asses for GTPS. Resisted lateral rotation has the highest sensitivity (88%) and specificity (97.3%) when compared to resisted medial rotation and abduction.7 Resisted medial rotation has been most assessed but the results change based on the position of the hip during the test. The highest sensitivity is achieved when medial rotation is assessed through range from end of range lateral rotation in prone. The highest specificity is achieved when the test is done in 90° hip flexion.13

The FADER, OBER and FABER tests can also be added as they aim to increase the tensile load on the gluteal tendons.4 The FABER test has a sensitivity of 82.9% and a specificity of 90% while the Ober test has a sensitivity of 41% and a specificity of 95%.7 Fearon et al. (2012) found that the FABER test was the key test when differentiating between hip OA and GTPS, where a positive FABER with lateral hip symptoms indicates GTPS.20 As mentioned previously, the ability to put one’s socks and shoes on without help will also help differentiate GTPS from OA, where the GTPS patient has no difficulty during the acitivity.4

The “jump sign” carries a PPV of 83% so direct palpation of the greater trochanter is helpful in diagnosing GTPS.4 The Trendelenburg sign is present in patients with GTPS and when used to assess for a GMed tear, it has a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 77%.14

If external coxa saltans is suspected, the suggested clinical tests include FABER, Ober test, Hula-Hoop test and active hip flexion followed by passive extension and abduction.26

Imaging is only suggested in the following situations:

- When it comes to diagnosing gluteal tears. Ultrasound or MRI should be used to confirm the diagnosis if suspected clinically22,14. Cook (2020) reports that ultrasound is the most accurate when assessing a tendon where MRI is helpful for differential diagnosis.41

- When conservative treatment has failed14,7

- When diagnosis is unclear14,7

Below is a diagnostic flow chart created by Speers and Bhogal (2017) for the 3 most common causes of lateral hip pain.4

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- VISA-G - GTPS-specific outcome measure21

- HOOS - Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

- HHS - Harris Hip Score

- iHOT - International Hip Outcome Tool

Examination[edit | edit source]

GTPS is a clinical diagnosis which means the diagnosis is based on the medical history as well as the signs and symptoms. This means that the assessment must include a good subjective assessment, so as to gather the necessary information regarding the signs and symptoms. Aside from doing a proper hip assessment, the below special tests can be used to help confirm or negate the suspected diagnosis of GTPS. In 2017, Ganderton et al. validated the following tests for GTPS: FABER, resisted external derotation test, greater trochanter palpation and resisted abduction.39 Please click on the link to each test for more detailed information regarding each test.

Trendelenburg Test: This is a quick test for assessing hip abductor muscle function and it can also be used to help determine if a tear is present in the hip abductors.A drop of the pelvis on the contralateral side of the stance leg indicates weakness of the stance leg's hip abductors and results in a positive test. Test administration is demonstrated here.

FABER Test: FABER is the acronym for flexion, abduction, external rotation. It is very helpful in confirming GTPS20 and it assists with differentiating between hip OA and GTPS.4

Noble Test: This is used to verify Iliotibial tightness and helps to distinguish iliotibial tightness from other common causes of lateral knee pain, such as lateral collateral ligament strain, bicipital or popliteal tendinopathy, knee OA and lateral meniscal pathology.52Test administration is demonstrated here.

Modified Ober’s Test:This test and its modification are used to assess the TFL and ITB. The test is positive if the thigh does not go further than 10 degrees adduction.

Renne’s Test: This test is used to assess ITB syndrome and can be done alone or in conjunction with the Noble Test.

(30 second ) Single leg stance test: The person being tested must stand, unassisted, on one leg with their eyes open and one finger on a wall. As soon as the person’s foot is lifted of the floor, the 30 seconds start. A positive test for patients with GTPS is lateral hip by 30 seconds. Grimaldi and Fearon (2015) suggest holding the position until reproduction of symptoms.7

Resisted external de-rotation test and modified external de-rotation test: The patient lies in supine and the examiner then passively flexes the hip to 90° with external rotation. The hip should be in neutral abduction/adduction. Slightly reduce the external rotation to decrease the compression of the tendon. The patient then actively rotates their leg to neutral against the therapist’s resistance. The modified test is exactly the same, but done in full hip adduction.39

Resisted abduction test: The examiner passively abducts the testing-limb to 45° abduction, with the patient in side-lying. The patient must then maintain this position against the examiner’s resistance. The resistance must be applied 1cm superior to the lateral malleolus.39

Management[edit | edit source]

The management of GTPS remains unclear, but the main goals of treatment are:

- Managing loads on hip joint

- Reducing compressive forces across greater trochanter

- Strengthen gluteal muscles

- Treating comorbidities.

Most of cases of GTPS can be managed in primary care with:

- Weight loss.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

- Targeted physical therapy, load modification, and optimisation of biomechanics.

- Adjunct therapies include shock wave therapy[1] and therapeutic ultrasound. Corticosteroid injection (CSI) can be effective in recalcitrant cases.

- Surgical intervention is reserved only for failed conservative management.[2]

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

Removal of the bursa (also known as bursectomy):

This intervention used to be carried out by open surgery, but now it is most commonly done arthroscopically. In this operation they first split the tensor fascia latae, because it lies over the greater trochanter. Then the tension on the iliotibial band is released and the inflamed bursa is removed. In a study of Fox et al. they found that arthroscopically performed trochanteric bursectomy is a minimally invasive technique that appears to be both safe and effective for treating recalcitrant pain syndromes as GTPS.[3][4]

Release of the Tractus iliotibialis:

The surgeon makes an incision at the level of the greater trochanter, and this incision will reduce the tension. This treatment has also been found to be effective but it only works on a short term. After a while the tractus will heal, and there can be a new friction due to the scar tissue.[4]

Reduction-osteotomy of the greater trochanter:

After the incision of the tensor fascia latae, the greater trochanter is reduced by making a longitudinal incision over the greater trochanteric and slicing the bone 5 or 10 mm in thickness. Afterwards the trochanter is repositioned more distally and fixated by means of two cortical lag screws with washers. By doing so, friction between the tractus iliotibialis and the trochanter major will be strongly reduced. A study by Govaert et al., concluded that a trochanteric reduction osteotomy is a safe and effective procedure for patients with refractory GTPS who do not respond to conservative treatment.[5]

[5]

Reconstruction of the abductor tendon:

When MRI and clinical findings are consistent with tendon disruption and weakness of the abductor tendons, surgical repair can be an option. A retrospective study by Davies et al. (2013) revealed substantial and durable improvement in strength and clinical performance after surgery in most cases. (Level IV)[6]

Non-Surgical Intervention[edit | edit source]

Treatment with corticosteroid injections are also possible. Brinks et al. (2011) found a positive short term effect of the corticosteroid injections in primary care patients with GTPS, but on the long-term, these injections no longer had a significant effect. We can conclude that corticosteroid injections are a good solution to give patients an early relief of pain.[7] This is done in order to break the pain cycle, to allow muscle strengthening and stretching, and to make some biomechanical adaptations to the lower extremity. By doing these corrections we are trying to remove or reduce the irritating force on the greater trochanter.[8][9][10][11][12]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

When GTPS is diagnosed in a patient, it is generally an overuse injury. [13] Treatment through physiotherapy is possible. The aim of a physical rehabilitation program is to reduce the acute or chronic pain, improve hip range of motion, improve sleep by decreasing pain with side lying and restore the overall function. [14]

First a wait-and-see policy is recommended. This means that the patient must rest and modify its activities (avoiding lying/sleeping on the affected area, no sitting with the legs crossed). The use of crutches or other walking aids (orthotics) may also be recommended.[14]

The use of therapeutic modalities, manual therapy and therapeutic exercise is described below, as based on Wyss & Petal (2012):

Therapeutic Modalities[edit | edit source]

- Ice and heat: During the acute phase, it might be useful to use ice for 20 minutes on the painful side, this every 2 or 3 hours [11][14]For chronic cases, ultrasound therapy (deep heating) appears to be clinically useful in greater trochanteric pain syndrome. It had a high positive predictive value for gluteal tendon tears (positive predictive value = 1.0). Patients reported high levels of pain relief and function after surgery; tendon and bursa showed pathologic changes. [15]

- Low-Energy Extracorporal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT): has been found effective for pain relief in patients witch chronic greater trochanteric pain syndrome. The intervention will not ensure that the syndrome goes away, but will provide effective pain relief. After palpation, the points of pain are localized, and are each applied with 600 shockwaves. More than one intervention is needed, as after one intervention the pain will not be reduced. [16]

- Iontophoresis, phonophoresis, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): and cold laser are all possible therapeutic modalities that could be useful for GTPS but are not yet supported by sufficient evidence.[14]

Manual Therapy[edit | edit source]

- Generally taken, manual therapy (deep tissue massage, myofacial release techniques, soft tissue mobilization) can be applicated to any restriction in soft tissue or joint at the hip, lumbar spine, pelvis, knee, ankle or foot in order to improve the gait, restore the normal hip mechanics and diminish the frictional force on the lateral hip. Nevertheless, more research is needed to support manual therapy as one of the additional treatments of GTPS. [14]

Therapeutic Exercise[edit | edit source]

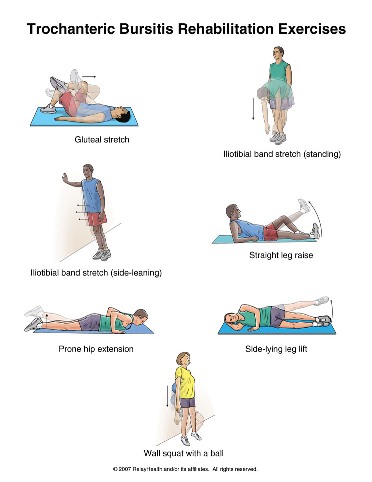

- The objective of therapeutic exercises is to improve the flexibility and strength of the affected hip. By obtaining an appropriate range of motion and muscular strengthening of the hip, the muscular balance and coordination of the buttock and hip muscles will be restored. As a result, the risk of relapsing from Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome can be strongly reduced.[14]

- Many patients with GTPS experience hip joint stiffness and restricted ROM on the affected side. Restoring normal hip ROM can be achieved with active, active assisted and passive range of motion as well as stretching.[14]

- To work on the flexibility of the hip, a stretching of the illiotibial band (IT band) and the tensor fascia latae (TFL) is performed.[11] This ensures that the compression and rubbing on the greater trochanter reduces. [17] Furthermore, stretching exercises can be done to decrease length deficits of the glutei, hamstrings, quadriceps and piriformis.[14]

- It is also needed to focus on strengthening of the hip abductors (especially the gluteus medius), external rotators end extensors, as well as the knee extensors and core muscles to improve gait, hip biomechanics and pelvic stability or control.[14]

Sample Treatment Plan[edit | edit source]

PHASE I - Pain Relief & Protection[edit | edit source]

- Management of pain. Pain is the main a patient will seek treatment for GTPS. It is believed that pain is it the final symptom developed but should be the first symptom to improve.

- Managing pain is best achieved through relative rest, ice therapy, and techniques or exercises that unload the injured structures.

- Eliminating the compressive Load is vital to the recovery of GTPS. Encourage and educate a patient to avoid positions that lengthen the affected hip including crossing your legs, lying on either side, walking on angled surfaces and in the initial stages stretching the muscles on the outside of the hip.

- You can use an array of treatment tools to reduce pain and inflammation. These include ice, electrotherapy, acupuncture, unloading taping techniques, soft tissue massage to off-load the affected side.

- If the pain does not resolve, you can consider a local corticosteroid injection.

PHASE II - Restoring Normal ROM, Strength[edit | edit source]

- As a patients pain and inflammation settles, focus is placed on restoring normal hip joint range of motion, muscle length and resting tension, muscle strengthening and endurance, proprioception, balance and gait (walking pattern).

- Treat comorbidities- osteoarthritis, labral tears can frequently coexist.

PHASE III - Restoring Full Function[edit | edit source]

The final stage of rehabilitation is aimed at returning to desired activities and functional independence. Specific treatment goals are needed to help a patient acheive their desired outcome and retrun to baseline level of activity.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Brukner P. Brukner & Khan's clinical sports medicine. North Ryde: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- ↑ Speers CJ, Bhogal GS. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a review of diagnosis and management in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2017 Oct 1;67(663):479-80.

- ↑ Bird PA, Oakley SP, Shnier R, et al. Prospective evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging and physical examination findings in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 2001; 44(9): 2138-2145.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Fox LJ. The role of arthroscopic bursectomy in the treatment of trochanteric bursitis. The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, 2002; 18(7): 1–4.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Govaert LHM, van der vis HM, Marti RK, et al. Trochanteric reduction osteotomy as a treatment for refractory trochanteric bursitis. JBJS, 2003; 85B(2): 199-203.

- ↑ Davies J, Stiehl J, et al. Surgical Treatment of Hip Abductor Tendon Tears. JBJS-America, 2013; 95A(15): 1420-25.

- ↑ Rothschild B. Trochanteric area pain, the result of a quartet of bursal inflammation. World J Orthop, 2013; 4(3): 100–102.

- ↑ Brinks A, van Rijn RM, Willemsen SP, et al. Corticosteroid Injections for Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Primary Care. Annals of Family Medicine, 2011; 9(3): 226-234.

- ↑ Kaprinski MRK, Piggot H. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome, a report of 15 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1985; 67B(5): 762-63.

- ↑ Rompe JD, Segal NA, Cacchio A, Furia JP, Morral A, Maffulli N. Home training, local corticosteroid injection, or radial shock wave therapy for greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Am J Sports Med, 2009; 37(10): 1981-1990.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Grumet RC, Frank RM, Slabaugh MA, et al. Lateral Hip Pain in an Athletic Population. Differential Diagnosis and Treatment Options. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 2010; 2(3): 191-96.

- ↑ Rowand M, Chambliss ML, Mackler L. Clinical inquiries: How should you treat trochanteric bursitis? J Fam Pract, 2009; 58(9): 494-500.

- ↑ Niemuth PE, Johnson RJ, Myers MJ, Thieman TJ. Hip muscle weakness and overuse injuries in recreational runners. Clin J Sport Med, 2005; 15: 14–21.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 Wyss J, Patel A (2012).Therapeutic Programs for Musculoskeletal Disorder: Demos Medical Publishing.

- ↑ Long S, Surrey D, Nazarian L. Sonography of Greater trochanter Pain Syndrome and the Rarity of primary Bursitis. American journal of Roentgenology, 2013; 201(5): 1083-1086.

- ↑ Furia JP, Rompe JD, Maffulli N. Low-Energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy as a treatment for greater trochanteric pain syndrome. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2009; 37(9): 1806-1837.

- ↑ Klingenstein GG, Martin R, Kivlan B et al. Injuries in the Overhead Athlete. Clinical Orthopeadics and related Research, 2012; 470(6): 1579-1585.