Exercise Therapy in the Rehabilitation of Spondylolisthesis in Fast Bowlers in Cricket: Difference between revisions

(introduction and epidemiology sections) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

The prevalence of lumbar spondylolysis in the normal population is 3-6%, compared to 48.5% in athletes presenting to sports medicine facilities, and up to 24-81% in cricket fast bowlers (Arora). However, pars stress lesions in the general population may well be asymptomatic, whereas similar injuries in sporting populations tend to be symptomatic (Johnson). Sixty-five percent of spondylolysis cases progress to spondylolisthesis (Syrmou et al 2010). | The prevalence of lumbar spondylolysis in the normal population is 3-6%, compared to 48.5% in athletes presenting to sports medicine facilities, and up to 24-81% in cricket fast bowlers (Arora). However, pars stress lesions in the general population may well be asymptomatic, whereas similar injuries in sporting populations tend to be symptomatic (Johnson). Sixty-five percent of spondylolysis cases progress to spondylolisthesis (Syrmou et al 2010). | ||

Elliot (1992) found in a sample of 20 fast bowlers from the Western Australia fast bowling development squad (mean age 17.9 years) that bony abnormalities were present in 55%. | Elliot (1992) found in a sample of 20 fast bowlers from the Western Australia fast bowling development squad (mean age 17.9 years) that bony abnormalities were present in 55% but, as with the vast majority of the literature, no figures were reported for spondylolisthesis specifically.. | ||

Age of athletes | Age of athletes | ||

Revision as of 13:22, 28 May 2018

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Lumbar stress fractures are responsible for up to 15% of all missed playing time in cricketers (Orchard). This article will describe the mechanism and prevalence of these injuries in cricket and detail the role of exercise therapy in the rehabilitation of fast bowlers following spondylolisthesis.

Objectives[edit | edit source]

- Discuss pathology and epidemiology of spondylolisthesis in cricketers

- Provide an in-depth evidence-based, Exercise Therapy Rehabilitation programme for cricketers

Pathology and Classification[edit | edit source]

Pathology: Lumbar stress fractures to one or both of the pars interarticularis of the lumbar vertebrae are termed spondylolysis (Arora). In the case of bilateral pars fractures, the vertebral body is unstable and able to translate anteriorly on the vertebra below. This anterior translation of the superior vertebra on the inferior vertebra is termed spondylolisthesis.

Lumbar spines of fast bowlers are subjected to repeated sagittal and transverse plane movements under load which leads to accelerated degenerative changes to the architecture of the lumbar spine (arora).

Categorisation: The typical category of spondylolisthesis seen in fast bowlers is the Wiltse Type 2: Isthmic spondylolisthesis, most commonly observed at L5-S1, which results from stress fractures to the pars interarticularis. These stresses are highest in extension and rotation which are present to a great extent in the delivery action of fast bowlers. More on the classification can be found here.

Grading: Grading of spondylolisthesis is made in reference to the degree of slippage of the affected vertebra in relation to the inferior vertebra (radiopaedia).

Biomechanics of Bowling[edit | edit source]

Mixed action: There are three main bowling actions for fast bowlers, referring to the angle of the hips and shoulders in relation to the direction of bowling: front on, side on and mixed. The mixed action is defined as a difference of ≥40o between the hip and shoulder angles and a high degree of counter-rotation of the shoulders (Ranson) and has an increased correlation with lumbar injury (Arora) due to the high degree of extension and rotation and lateral flexion experienced by the lumbar spine during the delivery stride. The ‘crunch factor’ – the product of lateral flexion and axial rotational velocity of the lumbar spine – has been implicated in the development of contralateral lumbar spine injuries in fast bowlers (Morton).

Ground reaction forces: Peak ground reaction forces during the delivery stride can reach 4.1-9 times bodyweight, which is transmitted through to soft tissue and bony structures including the lumbar facet joints (McGrath). If the front foot is planted whilst the lumbar spine is in combined rotation, extension and side flexion the axis of stress on the spine is altered, increasing the load on the pars interarticularis meaning the forces are not absorbed by the lumbar spine in the normal way and leading to increased risk of injury (McGrath).

Bowling frequency/workload: First class bowlers can deliver 300-500 balls per week during the season (McGrath). This load must be appropriately managed as too many overs in a spell, or too many spells without adequate recovery leads to fatigue and increased predisposition to injury as bowling technique deteriorates (Ross 1996a from McGrath), e.g. increased counter-rotation of shoulders can be observed to increase over the course of an eight-over spell of fast bowling (Johnson 2011).

Recovery between games is also linked to injury risk. A prospective study of junior fast bowlers (Dennis 2005 from Johnson) found those having less than 3.5 days recovery between bowling are over three times more likely to sustain an injury (RR = 3.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 8.9). Of these injuries, 11% were lumbar vertebral stress fractures.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of lumbar spondylolysis in the normal population is 3-6%, compared to 48.5% in athletes presenting to sports medicine facilities, and up to 24-81% in cricket fast bowlers (Arora). However, pars stress lesions in the general population may well be asymptomatic, whereas similar injuries in sporting populations tend to be symptomatic (Johnson). Sixty-five percent of spondylolysis cases progress to spondylolisthesis (Syrmou et al 2010).

Elliot (1992) found in a sample of 20 fast bowlers from the Western Australia fast bowling development squad (mean age 17.9 years) that bony abnormalities were present in 55% but, as with the vast majority of the literature, no figures were reported for spondylolisthesis specifically..

Age of athletes

Higher rates of injury are seen in younger bowlers (stretch 95), however there may be an element of subject bias as studies investigating lumbar bony stress injuries tend to recruit young participants (Johnson 2011). Experimentally, repetitive loading of cadaveric spines from 14-30-year-old subjects showed that spines from subjects younger than 20 years old were more susceptible to fracture through the pars interarticularis. A possible explanation for this is the greater elasticity of the intervertebral discs in younger spines, resulting in the transmission of greater shear forces to the facets and neural arch, which may not be completely ossified before the age of 20 (johnson 2011).

Location of injury

Given the mechanics of the delivery stride, pars stress fractures tend to be found more frequently (81% vs 19%) on the non-dominant side (Arora) i.e. the left side of the lumbar spine in a right-handed bowler. One small study of 36 fast bowlers found six of seven pars stress fractures were at L5 level, with two being bilateral (Ranson). L5-S1 is the most vulnerable level to pars fractures due to the high loading forces and quick changes in direction between the spine and the pelvis which occur here (Johnson).

In an 18-year period, all cricketers playing for a county club in England being referred by the physiotherapist for musculoskeletal back injuries causing missed game time lasting longer than two weeks were included in a study looking at surgery in lumbar stress fractures (Ranawat). Pars interarticularis defects were diagnosed in 18 players, with an average age of 20.8 years. Nine of these were bilateral, of which five were associated with spondylolisthesis. Seven of the nine unilateral defects were on the non-bowling arm side. Seven of the players included were opening pace bowlers. Amongst the bowlers, 20 lesions were detected, two at L1, two at L3, four at L4 and 12 at L5. Eight players responded well to conservative management, with 10 requiring surgical intervention (Ranawat).

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

For athletes who do not progress with conservative management, surgery may be considered as an alternative management strategy. Further indications for, and methods of surgery for spondylolisthesis are outside the scope of this article but are discussed in detail here.

In the 18-year study mentioned above (Ranawat), it is important to highlight the fact that all players, whether treated conservatively or surgically, returned to professional cricket, including international level, with no reported decease in performance. This suggests these are manageable injuries , with good rehabilitation potential if treated appropriately.

Exercise Therapy[edit | edit source]

Exercise Therapy is part of the conservative approach that is recommended for some athletes who have a spondylolisthesis. It is important as a physiotherapist to ensure that athletes have had medical clearance from a doctor before beginning a rehabilitation programme. Here we will discuss the Exercise Therapy programme that we have created based upon current literature/protocols that pre-exist (for athletes) for a cricketer (Uwhealth.org,2018; Nau, Hanney and Kolber, 2008).

(Mail-Online,2013) - picture reference

Phase One - ‘Rest and Protection’.[edit | edit source]

The rehabilitation goals of this stage are:

- allow adequate time for healing to occur

- initiate abdominal and spinal stabilisers

- Improve flexibility of key muscles

For healing to occur, there needs to be a period of rest. This component where aggravating activities are stopped is consistent throughout literature. A comprehensive review discussed management of low-grade spondylolisthesis in athletes. They included 14 studies investigating conservative treatment. They argued that rest is essential for management. In soccer athletes, they found that athletes who underwent activity modification as treatment rather than rest had worse outcomes in terms of return to sport in terms of time loss, but also in pain and function (Bouras and Korovessis, 2015) . Iwamoto (2010) in his return to sport article also agreed that a period of rest should be included, and that the aim is to be pain free during daily routine activities before any sport-specific exercises or strengthening exercises occur. It is this rest period that enables athletes to return pain-free to competition. Expert John Orchard who is chief medical officer for Australia Cricket reported that it is crucial that we unload our athletes before we carry out rehabilitation. The controversial point in the literature is on the duration of rest, some saying 4-6 weeks and others arguing up to 3 months.

There is debate in literature with regard to bracing during this period of rest. Literature suggests that bracing is considered if the athlete is still symptomatic after 2-4 weeks. However in a recent meta-analysis, they have reported that bracing is ineffective on outcomes. The aim of rest is to reduce extension stress of the lumbar spine and to promote anti-lordotic posture, so some authors believe bracing can help (Klein, Mehlmann and McCarty, 2009).

Next goal was to start to include core stabilisation exercises. From experts opinion, athletes tend to focus on the larger muscle groups and neglect the muscles (transverse abdominis, paraspinals, internal and external obliques, rectus abdominus and multifidus) responsible for spinal stabilisation. Strengthening these muscles can provide support by lifting the spine and maintaining neutral pelvic alignment thus transferring the force and thereby decreasing the amount of load to the area. Furthermore, transverse abdominis and multifidus have local stabilisation able to prevent excessive movements at regions of instability or hypermobility. These two groups of muscles will co-contract to provide a balanced effect in the spine. Multifidus is a deep muscle which attaches directly into the vertebra, therefore it is crucially important we provide exercises to work this muscle (Nau, Hanney and Kolber, 2008). A systematic review on risk factors and successful interventions for cricket related LBP recommended stabilisation exercises to reduce pain and increase the anterior abdominal slide (Morton et al., 2013).

The final goal was to improve flexibility of the key muscles. Standaert and Herring (2007) explain the importance for a broader kinetic chain assessment (pelvic and hamstrings, glutes) . Flexibility is an important component of spinal conditioning programs. Sometimes athletes may present with a secondary finding of hamstring or paraspinal muscle tightness perhaps to offer some sort of stabilisation. Exercises to address flexibility of the hamstrings, rectus femoris and tensor sascia latae musculature have been recognised as an integral component of the spinal conditioning program in those with spondylolitic disorders. This tightness can increase the lumbar lordosis due to direct effects on pelvic alignment, increasing strain on already unstable vertebrae. Static stretching is advocated for a duration of 30 seconds for 3 repetitions, twice a day, daily. With all of the stretches we have prescribed or recommended we are looking for it to remain pain-free. If a stretch induces pain, relieve pressure until pain-free and start again (Nau, Hanney and Kolber, 2008).

During this phase, it is crucial that athletes avoid lumbar extension to avoid stressing the lumbar spine. The duration of the first stage varies amongst different athletes. It is important that there is adequate time left to rest and be pain-free to allow healing to occur before progression onto the second phase (Perrin, 2016).

Exercises include in this phase are:

- Dynamic Hamstring 90/90 stretch

- Supine figure four Piriformis stretch

- Transverse Abdominis contractions in prone, supine and standing postures

See a summary of phase one below:

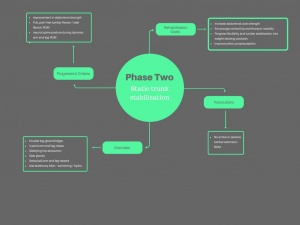

Phase Two - 'Static Trunk Stabilisation'.[edit | edit source]

The rehabilitation goals of this stage are:

- Increase abdominal strength

- Encourage normal hip and thoracic mobility

- Progress flexibility and spinal stabilisation

- Improve pelvic proprioception

Experts argue that early stages of strengthening exercises should be supervised and well-educated to ensure that technique is mastered and exercises are improving the correct components you are aiming for (Mallac, 2012).

Strengthening exercises are regarded as important. A systematic review (Hardwick et al., 2012) investigating outcomes of strengthening approaches for low grade spondylolisthesis found that both strengthening and stabilisation exercises are important and can be of benefit. It shared the view of other experts that strengthening programmes significantly improve pain and stabilisation exercises reduce disability (Miller, 2018).

Phase two builds upon the foundations that you have laid from phase one (see above). This phase is looking to further progress flexibility of key muscles of the kinetic chain (hamstrings, hip flexors), in order to further optimise pelvic alignment and prevent any further stress on the lumbar spine. The same exercise prescription advice is given as in phase one (see above)

There are progressions of the core stabiliser exercises used to further work on stabilising the spine aiming to reduce pain and disability in order. Stuart McGill (McGill, 2007) believes that lumbar stabilisation exercises are crucial for athletes with LBP as they can lead to optimal athletic performance reducing pain. He suggested core stabilisation exercises in different postures help adapt to function and different environments that athletes are required to work in. He argued that an exercise programme addressing multifidus can pull the vertebra backwards . Another systematic review agrees that they can reduce pain and disability (Garet et al., 2013). These exercises initially should be performed daily to improve neural activation and motor unit recruitment, then as time progresses and pain and disability is reduced performed 2-3 times a week to improve muscular performance. With each core stability exercise, I would recommend 10-15 repetitions of 1 set, aiming to progress up to 3 sets (McGill, 2007).

In phase two, there may also be an inclusion of some manual therapy. Recent literature (Mohanty et al., 2015) has shown that myofascial release into thoraco-lumbar fascia, passive stretching techniques and central mobilisations into hypomobile cervico-thoracic segments are more effective at significantly reducing pain and disability , in comparison to a conventional home exercise programme.

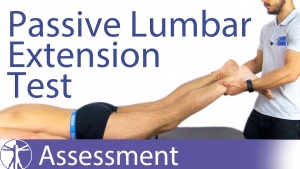

It is important to monitor progression throughout rehabilitation phases using outcome measures, tests or exercises to do this. Literature shows that using exercises incorporated in the rehab protocol is quicker, and can be more motivating for the athlete (Ferrari, Vanti and O’Reilly, 2012). An aspect that will be constantly monitored is pain. It is essential that all exercises in phase one and two are pain-free, so if anything is painful, regress the exercises until pain-free. A number of tests are recommended to be used for athletes. For instability, the prone instability test and the passive lumbar extension test. Muscle tests that can be used include the active straight leg raise, hamstring 90/90 test, double leg and single leg bridge. For abdominal strength, the plank and side plank will be a measure.

(PhysioTutors, 2017) - picture reference

Exercises included in phase two are:

- Double leg gluteal bridges

- Side-lying Clam

- Side-lying Hip abduction (ensuring no lumbar extension)

- Side Plank

- Superman Transverse Abdominis Progression (Bird-Dog) (ensuring no lumbar extension)

- Swiss Ball Leg and Arm Raises

- Plank

- Pelvic Proprioception Exercises

- Flexibility exercises from phase one

See a summary of phase two below:

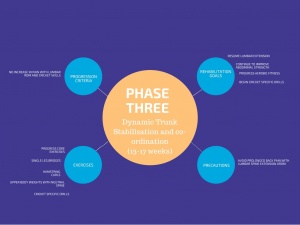

Phase Three -[edit | edit source]

The goals of this phase of the rehabilitation program are;[edit | edit source]

- Resume lumbar extension

- Progress static core exercises to dynamic ones

- Resume aerobic fitness

- Introduce cricket specific drills

In this phase of the rehabilitation program it is important to implement the use of dynamic trunk stabilization exercises (Ikeda). This reduces the bio-mechanical stresses on the lumbar spine and is a key component of a rehabilitation plan for spodylolisthesis (Perrin). The athlete should be performing these dynamic stabilization exercises in the stegth range of repetition 8-12 per set, with the aim to complete 3 sets every other day (Talukdar).

It is in this phase the athlete should resume aerobic fitness drills, however at this stage they should be non weight bearing activities such as swimming or cycling, before moving on to activities like jogging and running (Perrin)

The athlete should continue to incorporate lumbar range of motion exercises in this phase, but it is the introduction of extension exercises tat differentiates this phase from phase 2. It is important for the athlete to be able to perform pain free lumbar extension before starting to partake in cricket specific skill drills (Bouras and Korovessis).

Once pain free, full range, lumbar extension has been achieved the use of cricket specific drills and movements in the rehabilitation program is the next progression, this will help the athlete prepare for a return to sport (Iwamoto). The key precaution in this phase is to not introduce sport specific drills too early and ensure full lumbar extension can be achieved without any pain (Dubousset). In order to move on to the next phase of the rehabilitation program the athlete must be able to demonstrate the ability to perform functional drills without any pain or compensations

Some of the exercises to be included in this phase are;

- Single leg glute bridges

- Pallof press

- Cable rotational core exercises

- Cable wood chops

- Double/ single leg bosu ball stands

- Throwing drills

- Catching drills

- Lumbar spine ROM exercises

- Static bowling motion drills

See a summary of phase 3 below.

Phase Four - blah blah blah[edit | edit source]

Download full Exercise Therapy Rehabilitation Programme

Suggested Exercises[edit | edit source]

https://youtu.be/pgc5K_GkgTo - Please click here to see a video of suggested exercises based upon current literature for Cricketers with Spondylolisthesis.

Future Recommendations[edit | edit source]

It is important that cricketers are constantly completing exercises addressing flexibility and spinal stabilisation. These should be done throughout the year (not just during the season) to ensure the athlete is maintained in optimum condition and to prevent any injury. Therefore, it would be recommended that cricketers should be completing exercises like the ones recommended in this programme to prevent any spondylolitic disorders (McGill, 2007; (Nau, Hanney and Kolber, 2008).

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

blah blah blah