Cushing's Syndrome

Original Editors - Jessica Stevenson from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Jessica Stevenson, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Laura Ritchie, Aminat Abolade, Dave Pariser, Tony Lowe, Wendy Walker, 127.0.0.1, Kim Jackson and Kirenga Bamurange Liliane

Definition/Description

[edit | edit source]

Cushing’s syndrome is a general term for increased secretion of cortisol by the adrenal cortex.

- When corticosteroids are administered externally, a condition of hypercortisolism called iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome occurs.

- When the hypercortisolism results from an oversecretion of Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary, the condition is called Cushing’s disease.

The clinical presentation is the same for all of these conditions.[1] [2]

Epidemiolgy[edit | edit source]

The actual incidence and prevalence of Cushing syndrome are not known. The prevalence of the disease is highly variable across different ethnic and cultural groups depending upon the frequency and spectrum of the medical conditions requiring steroid-based therapy.

- Of the known cases iatrogenic hypercortisolism outweighs the endogenous causes,

- Of the endogenous causes pituitary-mediated ACTH production accounts for up to 80% of cases of hypercortisolism, followed by adrenals, unknown source, and ectopic ACTH production secondary to malignancies[3]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

There are two main etiologies of Cushing syndrome:

- Endogenous hypercortisolism: results from excessive production of cortisol by adrenal glands and can be ACTH-dependent and ACTH-independent. ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas (Cushing disease) and ectopic ACTH secretion by neoplasms are responsible for ACTH-dependent Cushing. Adrenal hyperplasia, adenoma, and carcinoma are major causes of ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome.

- Exogenous hypercortisolism: the most common cause of Cushing syndrome, mostly iatrogenic and results from the prolonged use of glucocorticoids[3].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

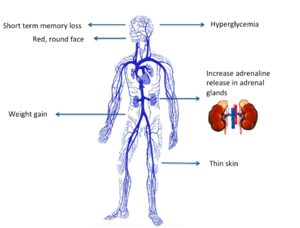

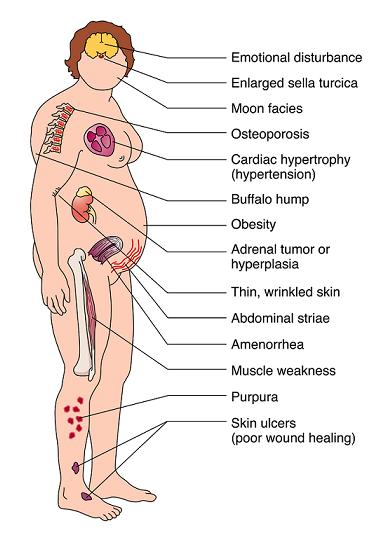

Clinical manifestations include “moon” face (very round), buffalo hump (truncal obesity with prominent supraclavicular and dorsal cervical fat pads) [4], protuberant abdomen with accumulation of fatty tissue and stretch marks with purple striae, muscle wasting and weakness, thin extremities, decreased bone density (especially spine), kyphosis and back pain (secondary to bone loss), easy bruising and poor wound healing due to thin and atrophic skin [4], acne, psychiatric or emotional disturbances, impaired reproductive function (decreased libido and changes in menstrual cycle, and diabetes mellitus. In women, masculinizing effects such as hypertrichosis, breast atrophy, voice changes, and other signs of virilism are noted. Cessation of linear growth is characteristic in children. [1] [4]

Image:Moon_facies_in_Cushings.jpg

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Cushing’s syndrome involves the HPA axis causing excess cortisol release from the adrenal glands. When the normal function of the glucocorticoids becomes exaggerated, a wide range of physiologic responses can be triggered. [2]

Co-morbidities involved with Cushing’s disease are persistent hyperglycemia, cardiac hypertrophy and hypertension, proximal muscle wasting (protein tissue wasting), osteopenia or osteoporosis, hypokalemia, mental changes and memory loss, depression, renal calculi, increased susceptibility to infection, adrenal hyperplasia and adrenal tumors [2] [4] [1]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Initially, the patient’s general condition should be supported by high protein intake and appropriate administration of vitamin K. If clinical manifestations are severe, it may be reasonable to block corticosteroid secretion with metyrapone 250 mg to 1 g pot id or ketoconazole 400 mg po once/day, increasing to a maximum of 400 tid. Ketoconazole is more readily available but slower in onset and sometimes hepatatoxic. [4]

Adrenal inhibitors, such as metyrapone 500 mg pot id (and up to a total of 6 g/day) or mitotane 0.5 g po once/day, increasing to a maximum of 3 to 4 g/day, usually control severe metabolic disturbances (eg. Hypokalemia). When mitotane is used, large doses of hydrocortisone or dexamethasone may be needed. Measures of cortisol production may be unreliable, and severe hypercholesterolemia may develop. Ketoconazole 400 to 1200 mg po once/day also blocks corticosteroid synthesis, although it may cause liver toxicity and can cause addisonian symptoms. Alternatively, the corticosteroid receptors can be blocked with mifepristone (RU 486). Mifepristone increases plasma cortisol but blocks effects of the corticosteroid. Sometimes ACTH-secreting tumors respond to long-acting somatostatin analogs, although administration for > 2 years requires close follow-up, because mild gastritis, gall stones, cholangitis, and malabsorption may develop. [4]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Taking glucocorticoid medications is the most common cause of Cushing syndrome. If this is the case other tests are not needed.

Cushing syndrome from endogenous cortisol production can be difficult to diagnose because other conditions have similar signs and symptoms. Diagnosing Cushing syndrome can be a long and extensive process. The below tests can help find the cause:

Urine and blood tests: measure hormone levels and show whether person is producing excessive cortisol. The doctor might also recommend other specialized tests that involve measuring cortisol levels before and after using hormone medications to stimulate or suppress cortisol.

Saliva test. Cortisol levels normally rise and fall throughout the day. In people without Cushing syndrome, levels of cortisol drop significantly in the evening. By analyzing cortisol levels from a small sample of saliva collected late at night, doctors can see if cortisol levels are too high.

Imaging tests. CT or MRI scans can provide images of the pituitary and adrenal glands to detect abnormalities, eg tumors.

Petrosal sinus sampling. This test can help determine whether the cause of Cushing syndrome is rooted in the pituitary or somewhere else. For the test, blood samples are taken from the veins that drain the pituitary gland (petrosal sinuses).

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Cushing’s syndrome involves the HPA axis causing excess cortisol release from the adrenal glands. Cortisol has a key role in glucose metabolism and a lesser part in protein, carbohydrate, and fat metabolism. Cortisol also helps maintain blood pressure and cardiovascular function while reducing the body’s inflammatory responses. Overproduction of cortisol causes liberation of amino acids from muscle tissue with resultant weakning of protein structures (specifically muscle and elastic tissue). The end result may include a protuberant abdomen with purple striae, poor wound healing, thinning of skin, generalized muscle weakness, and marked osteoporosis that is made worse by an excessive loss of calcium in the urine. [2] [1] In severe cases of prolonged Cushing’s syndrome, muscle weakness and demineralization of bone may lead to pathological fractures and wedging of the vertebrae, kyphosis, osteonecrosis (especially in femoral head), bone pain, and back pain. [2]

The effect of circulating levels of cortisol on the muscles varies from slight to marked. Muscle wasting can be so extensive that the condition simulates muscular dystrophy. Marked weakness of the quadriceps muscle often prevents affected people from rising out of a chair unassisted. [2] [1]

It is important to remember whenever corticosteroids are administered, the increase in serum cortisol levels triggers a negative feedback signal to the anterior pituitary gland to stop its secretion of ACTH. [1] This decrease in ACTH stimulation of the adrenal cortex results in adrenocortical atrophy during the period of exogenous corticosteroid administration. If these medications are stopped suddenly rather than reduced gradually, the atrophied adrenal gland will not be able to provide the cortisol necessary for physiologic needs. A life-threatening situation known as acute adrenal insufficiency can develop, requiring emergency cortisol replacement. [2]

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

| [5] |

Treatment to restore hormone balance and reverse Cushing’s syndrome or disease may require radiation, drug therapy, or surgery, depending on underlying cause (e.g. resection of tumors). For individuals with muscle wasting or at risk for muscle atrophy, a high-protein diet may be prescribed. Prognosis depends on the underlying cause and ability to control the cortisol excess. Cortisol-secreting tumors can recur, thus follow-up screening is advised. [2]

Pituitary tumors that produce excessive ACTH are removed surgical or extirpated with radiation. If no tumor is demonstrated on imaging but a pituitary source is likely, total hypophysectomy may be attempted, particularly in older patients. Younger patients usually receive supervoltage irradiation of the pituitary, delivering 45 Gy. Improvement usually occurs in <1 yr. However, in children, irradiation may reduce secretion of growth hormone and occasionally cause precocious puberty. In special centers, heavy particle beam irradiation, providing about 100 Gy, is often successful, as is a single focused beam of radiation therapy given as a single dose-radiosurgery. Response to irradiation occasionally requires several years, but response is more rapid in children. [4]

Bilateral adrenalectomy is reserved for patients with pituitary hyperadrenocorticism who do not respond to both pituitary exploration (with possible adenomectomy) and irradiation. Adrenalectomy requires life-long corticosteroid replacement. [4]

Adrenocortical tumors are removed surgically. Patients must receive cortisol during the surgical and postoperative periods because their nontumorous adrenal cortex will be atrophic and suppressed. Benign adenomas can be removed laparoscopically. With multinodular adrenal hyperplasia, bilateral adrenalectomy may be necessary. Even after a presumed total adrenalectomy, functional regrowth occurs in few patients. [4]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Therapists are more likely to treat people who have developed medication-induced Cushing’s syndrome. This condition occurs after these individuals have received a large dose of cortisol (also known as hydrocortisone) or cortisol derivitives. Exogenous steroids are administered for a number of inflammatory and other disorders such as asthma or rheumatoid arthritis. [1]

- Because cortisol suppresses the inflammatory response of the body, it can mask early signs of infection. Any unexplained fever without other symptoms should be a warning to the physical therapist of the need for medical follow-up. [1]

- Consult MD before beginning any exercise program. [6]

Get regular exercise to help maintain muscles and bone mass and prevent weight gain. To maintain muscle and bone mass, weight-bearing exercises such as push-ups, sit-ups, or lifting weights are helpful. To prevent weight gain, aerobic exercise is good to increase your heart rate. Examples of aerobic exercise include fast walking, jogging, cycling, and swimming. [6]

Education on avoiding falls and removing loose rugs and other hazards in the home. Falling may lead to broken bones and other injuries. [6]

Pay close attention to all wounds. Too much cortisol slows wound healing. Education on proper wound healing and cleansing is important. Clean all wounds immediately with antibacterial soap and use antibiotic ointment and dressings to prevent infection. [6]

Differential Diagnosis [edit | edit source]

Differential diagnoses for Cushing’s syndrome are obesity, diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, other metabolic and endocrine problems. [1]

Differentiation of Cushing syndrome from pseudo–Cushing syndrome can sometimes be a challenge. A pseudo-Cushing state is defined as having some of the clinical features and biochemical evidence of Cushing syndrome. However, resolution of the primary condition results in disappearance of the cushingoid features and biochemical abnormalities. [7]

In patients who chronically abuse alcohol, clinical and biochemical findings suggestive of Cushing syndrome are often encountered. Discontinuation of alcohol causes disappearance of these abnormalities, and, therefore, this syndrome is often specifically referred to as alcohol-induced pseudo-Cushing syndrome. [7]

Patients with depression often have perturbation of the HPA axis, with abnormal cortisol hypersecretion. These patients rarely develop clinical Cushing syndrome. Because excess glucocorticoids can lead to emotional liability and depression, distinguishing between depression and mild Cushing syndrome is often a diagnostic challenge. [7]

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

Click on links below to view case studies of patient's with Cushing's syndrome:

http://www.endocrinology.org/education/resource/EndocrineNurseCourse/ent03/ent03_kie.htm [8]

http://path.upmc.edu/cases/case144.html [9]

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/547281 [10]

http://www.nature.com/nrendo/journal/v3/n11/full/ncpendmet0665.html [11]

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15233560 [12]

Resources

[edit | edit source]

<uCushing's Syndrome Support Group: http://www.cushings-help.com/cushing-causes.htm

TEXTBOOKS

100 Case Studies in Pathophysiology.

Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral.

The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy 18th edition.

Pathology: Implications for Physical Therapists 3rd edition.

INTERNET RESOURCES

Cushing's Syndrome Support Website (http://www.cushings-help.com/cushing-causes.htm)

E-medicine (http://emedicine.medscape.com/)

Endocrine Pathology case study (http://path.upmc.edu/cases/case144.html)

Medscape Today from WebMD (http://www.medscape.com/medscapetoday)

PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed)

Society for Endocrinology (http://www.endocrinology.org/)

U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institute of Health. NCBI (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Goodman CC, Snyder KS. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. Philadelphia : W.B. Saunders Company; 2006: 473-475

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2009: 481-483.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Chaudhry HS, Singh G. Cushing syndrome. InStatPearls [Internet] 2021 Jul 30. StatPearls Publishing. Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470218/ (accessed 12.5.2022)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Beers MH, Porter RS, Jones TV, Kaplan JL, Berkwits M. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy 18th ed. Whitehouse Station:Merck Research Laboratories; 2006: 1212-1214.

- ↑ MauiMaryRN. Cushing's Disease. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OlIVt-Yv6I4 [last accessed 22/03/13]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Caroline Rea. Cushing's Syndrome. YahooHealth. last updated 4/29/2008. http://health.yahoo.com/hormone-living/cushing-s-syndrome-home-treatment/healthwise--hw71687.html

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Gail K Adler, MD, PhD, FAHA, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Hypertension, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School Cushing Syndrome: Differential Diagnoses & Workup Updated: Oct 1, 2009

- ↑ N Kieffer. Leicester Royal Infirmary, UHL NHS Trust Endocrine Nurses Training Course 10-12 September 2003: St Aidan's College, University of Durham, Windmill Hill, Durham DH1 3LJ

- ↑ Sanja Dacic, MD and Prabha B. Rajan, MD Endocrine Pathology Case Study. Published on-line in April 1998

- ↑ Ashley B Grossman; Philip Kelly; Andrea Rockall; Satya Bhattacharya; Ann McNicol; Tara Balwick[Case Study]: Cushing's Syndrome Caused by an Occult Source: Difficulties in Diagnosis and ManagementPosted: 11/21/2006; Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2(11):642-647. © 2006 Nature Publishing Group

- ↑ P Gerry Fegan, Derek D Sandeman, Nils Krone, Deborah Bosman, Peter J Wood, Paul M Stewart and Neil A Hanley. Cushing's syndrome in women with polycystic ovaries and hyperandrogenism. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004 Apr;27(4):375-9.

- ↑ Tung SC, Wang PW, Huang TL, Lee WC, Chen WJ. Bilateral adrenocortical adenomas causing ACTH-independent Cushing's syndrome at different periods: a case report and discussion of corticosteroid replacement therapy following bilateral adrenalectomy. Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan. [email protected]