Bowel Considerations with Spinal Cord Injury: Difference between revisions

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) (Corrected external link) |

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

In individuals with spinal cord injury, the pattern of bowel dysfunction varies depending on the level of injury. Complications associated with neurogenic bowel dysfunction include constipation, obstructive defecation, and faecal incontinence.<ref name=":0">Hughes M. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4174229/pdf/10-1055-s-0034-1383904.pdf Bowel management in spinal cord injury patients]. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2014 Sep;27(3):113-5</ref> Bowel dysfunction can significantly restrict a person's social activities and quality of life, so developing an optimal bowel management programme for each individual is essential.<ref>Khadour FA, Khadour YA, Xu J, Meng L, Cui L, Xu T. [ | In individuals with spinal cord injury, the pattern of bowel dysfunction varies depending on the level of injury. Complications associated with neurogenic bowel dysfunction include constipation, obstructive defecation, and faecal incontinence.<ref name=":0">Hughes M. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4174229/pdf/10-1055-s-0034-1383904.pdf Bowel management in spinal cord injury patients]. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2014 Sep;27(3):113-5</ref> Bowel dysfunction can significantly restrict a person's social activities and quality of life, so developing an optimal bowel management programme for each individual is essential.<ref>Khadour FA, Khadour YA, Xu J, Meng L, Cui L, Xu T. [https://josr-online.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13018-023-03946-8 Effect of neurogenic bowel dysfunction symptoms on quality of life after a spinal cord injury.] J Orthop Surg Res 2023; 18(458).</ref> This article supplies additional information on managing bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury for the Plus course: Bladder and Bowel Considerations with Spinal Cord Injury. | ||

== Bowel Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury == | == Bowel Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury == | ||

Latest revision as of 12:15, 19 March 2024

Original Editor - Wendy Oelofse

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

In individuals with spinal cord injury, the pattern of bowel dysfunction varies depending on the level of injury. Complications associated with neurogenic bowel dysfunction include constipation, obstructive defecation, and faecal incontinence.[1] Bowel dysfunction can significantly restrict a person's social activities and quality of life, so developing an optimal bowel management programme for each individual is essential.[2] This article supplies additional information on managing bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury for the Plus course: Bladder and Bowel Considerations with Spinal Cord Injury.

Bowel Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury[edit | edit source]

The symptoms of neurogenic bowel dysfunction vary depending on the patient's level of injury. Vallès et al. define three neuropathological patterns in patients with a complete spinal cord injury:[3][1]

- Pattern A: Patients with spinal cord injury above T7 AND:

- loss of voluntary control of abdominal muscles

- preserved spinal sacral reflexes

- Pattern B: Patients with spinal cord injury below T7 AND:

- voluntary control of abdominal muscles

- preserved sacral reflexes

- Pattern C: Patients with spinal cord injury below T7 AND:

- voluntary control of abdominal muscles

- absent sacral reflexes.

Neurogenic bowel can also be divided into:[4]

- Spastic (reflexic) bowel

- Flaccid (areflexic) bowel

Spastic Bowel[edit | edit source]

- Observed in people with a spinal cord injury above T12 (upper motor neuron SCI)

- May not feel the need to have a bowel movement

- Loss or impairment of voluntary control of the external anal sphincter

- The reflex that makes the stool move out of the body is intact and can be stimulated

- The outcome of spastic bowel is constipation, usually with faecal retention, but uncontrolled evacuation of the rectum can occur

Flaccid Bowel[edit | edit source]

- Observed in people with a spinal cord injury below T12 (lower motor neuron SCI)

- Cannot feel the need to have a bowel movement

- Loss or impairment of voluntary control of the external anal sphincter

- Loss of the bowel reflex - the rectum cannot easily empty itself, and the sphincter muscles may relax and stay open

- The outcome of flaccid bowel is usually constipation and incontinence

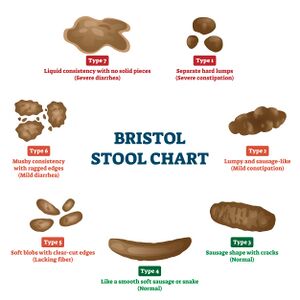

Bristol Scale[edit | edit source]

The Bristol Scale or Bristol Stool Chart is an assessment tool used by healthcare professionals to classify a patient's stool. It can be used to diagnose constipation, diarrhoea and irritable bowel syndrome.[5] Please see Figure 1 to understand the seven types of stool.

Management of Bowel Dysfunction[edit | edit source]

"The overall goal of bowel management is to achieve secondary continence with regular and sufficient bowel emptying within an individually acceptable time frame and at the right time according to the patient’s agenda."[6]

The literature does not support one specific bowel management programme for patients with spinal cord injury. A multidisciplinary team should assess each patient and choose a strategy that allows the individual to self-manage their bowel programme as much as possible.

Spastic Bowel Management[edit | edit source]

The following strategies are recommended to manage a spastic bowel.

- Bowel routine

- individuals usually take a stimulant laxative at a set time, 8-12 hours before the bowel routine (normally either an evening or morning routine)

- after 8-12 hours, a suppository can be inserted while the individual is lying down

- the individual then waits 10-15 minutes (although this time can vary), transfers to a commode/toilet, and performs digital stimulation (if needed)

- people with a spastic bowel will often aim to empty their bowel every other day or three times per week

- the bowel routine should take no longer than one hour

- Suppository

- bisacodyl and glycerin are the most common active ingredients in suppositories

- Digital rectal stimulation

- a gloved finger is inserted into the anorectal canal

- the goal is to enhance contractions of the descending colon and rectum, which helps with bowel evacuation

- should be used with caution as overstimulation can lead to increased incontinence and increased mucus production

- more information on digital rectal stimulation is available here: Digital Stimulation (Rectal Touches)

- Abdominal massage

- this can help when sitting on the commode/toilet

- takes about 15 minutes

- the goal of abdominal massage is to decrease colonic transit time, reduce abdominal distension and increase the frequency of bowel movements per week

- please note that there is "contrasting evidence on the effectiveness of abdominal massage in treating neurogenic bowel dysfunction. Further research is needed"[7]

- Stool consistency

- Aim for Bristol Scale Type 4

Please watch the video below if you would like to see a demonstration of abdominal massage to manage constipation.

Flaccid Bowel Management[edit | edit source]

The following strategies are recommended to manage a flaccid bowel.

- Bowel routine

- may take a stimulant laxative 8-12 hours before the bowel routine, but the aim is to decrease the use of laxatives slowly until none are required

- transfer to the toilet/commode

- stool is removed from the rectum using digital removal with a gloved finger

- to manage a flaccid bowel, the bowels may need to be emptied frequently (usually daily, but can be done every second day or twice per day)

- Digital removal

- insert a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum, gently hook and remove stool

- repeat every 5 minutes until the rectum is empty

- Suppositories

- glycerine suppositories may help to lubricate the rectum for easier stool passage

- Stool consistency:

- aiming for a firm stool consistency (Bristol Scale Type 2-3)

- achieved through a balanced diet, but sometimes requires the use of medication

Transanal irrigation[edit | edit source]

A randomised, controlled trial of transanal irrigation provides an example of a transanal irrigation system used by patients with spinal cord injury and neurogenic bowel dysfunction. The results of this study are as follows.[9]

- Transanal irrigation systems include a coated rectal balloon catheter, a manual pump, and a water container

- A balloon catheter is inserted into the rectum, and warm tap water is slowly administered in volumes of between 750 mL and 1500 mL of tepid tap water

- This system makes it possible for individuals with a spinal cord injury to handle the irrigation procedure without needing assistance from another person

- Immobilised patients and patients with poor hand function can use this system

- Outcomes: fewer reports of constipation, less faecal incontinence, improved symptom-related quality of life, and reduced time spent on bowel management procedures

For more information on transanal irrigation, please see pages 23-30 of Bowel dysfunction and management following spinal cord injury.

Colostomy[edit | edit source]

- A viable option for some patients[10]

- Can improve quality of life, reduce time spent on bowel care, and increase independence[11]

- Considered a good option for individuals who spend long hours on bowel management and when non-invasive procedures have not been sufficient[10]

- The most common complications include rectal discharge, stoma prolapse, further surgery to remove the remaining colon, wound healing issues and skin irritation[11]

For more information on colostomy, please see pages 35-39 of Bowel dysfunction and management following spinal cord injury.

Possible Causes of Frequent Bowel Accidents[edit | edit source]

- Medication can interfere with a bowel routine: certain medications can cause constipation, and others can cause diarrhoea

- Illness: can lead to diet changes or changes in mobility

- Patient's activity level: being mobile helps move stool through the colon

- Hot weather: increased temperature can lead to dehydration, which results in constipation

Bowel Complications[edit | edit source]

- Consistency: diarrhoea

- Consistency: constipation

- Haemorrhoids/rectal bleeding

- Autonomic dysreflexia

- Skin breakdown

Assessment for Independent Use of the Toilet for Bowel Care[edit | edit source]

Hand function[edit | edit source]

- Does the patient have sufficient hand function to perform digital interventions?[4]

- Individuals with a complete spinal cord injury above C8 will not be able to perform independent bowel care due to a lack of sufficient motor power and sensation in the fingers[4]

- Some individuals may achieve reliable emptying after rectal stimulant insertion without the need for digital checking or further digital stimulation, but many do require these additional interventions[4]

- There are aids available to insert liquid stimulants and to assist with cleaning, but there is no aid available to help with digital checking/stimulating[4]

Toilet access[edit | edit source]

- An individual may sit directly on the toilet or sit on a shower chair over the toilet[4]

- Wherever possible, an individual should be instructed on independent toilet transfers, but please note falls from the toilet are common and can cause significant injury[12]

- Using a shower chair can reduce the need for transfers between the wheelchair/shower chair/toilet, but there are some key points to consider:[4]

- shower chairs can be difficult to balance on for self-care

- while self-management can be learned using a shower chair, it can limit future lifestyle options if toilet use is not also learned

- for instance, while portable shower chairs are available, it can be difficult to take one everywhere you go, so if an individual with spinal cord injury cannot use a toilet, they would need to carry out their bowel care in bed if a portable chair isn't available[4]

- Adapted toilet facilities should be accessible for a wheelchair and have handrails and a padded/contoured toilet seat; a home visit by an occupational therapist may be required[4]

Skin Integrity[edit | edit source]

- All individuals with diminished or absent sensation and who require prolonged toileting should use a pressure-relieving seat for the toilet or shower chair[13]

- please note this only reduces the risk of pressure damage; it does not eliminate it

- Individuals with a history of skin damage and resultant scarring may not safely tolerate even a short sitting time[4]

- Minimising the duration of bowel care through an effective and timely bowel management programme is essential[4]

Assessing for Carer Assisted/Dependent Bowel Care[edit | edit source]

- The safety of the carer is paramount in supporting a client’s bowel management over the toilet/ or on a shower chair - a specific risk assessment must be undertaken to establish the risk to all parties

- Check if it is possible to use a shower chair as this minimises transfers and optimises carer access to the anal area

- Consider if the physical environment and patient’s size and shape allow easy and safe access for all interventions required by the individual (e.g. insertion of rectal stimulants, digital rectal stimulation, checking and cleaning)

- Is the carer constantly available during the procedure, or can the individual safely be left alone for periods during bowel management?

General Factors for a Successful Bowel Programme[edit | edit source]

General factors to consider when planning caregiver training include the following:

- Patient and caregiver motivation

- Skin condition

- General health/frailty (i.e. postural hypotension, extreme old age)

- Degree of spasticity

- Sitting balance

- Home circumstances: privacy and dignity, accessibility, availability of suitable equipment

An individual who is physically dependent for bowel care should be supported to be verbally independent and to take control of and responsibility for their bowel care. This means they should be able to instruct a carer on how to undertake their bowel management and to receive and act upon feedback from the carer regarding the outcomes of management. In either case, the individual requires knowledge and understanding of:[4]

- The impact of their neurological condition on their bowel function

- Theoretical knowledge of their bowel management interventions and influencing factors (e.g. diet and fluids, regular routine, etc)

- Practical skills for bowel management on the bed and/or toilet, as appropriate

- How and when to adjust the bowel regime

- How to identify complications and what action to take

- How to obtain supplies of disposable items required for bowel care in the community

- How to access assistance from healthcare professionals if required (e.g. contact details of specialist nurses providing support)

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Kurze I, Geng V, Böthig R. Guideline for the management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction in spinal cord injury/disease. Spinal Cord. 2022 May;60(5):435-443.

- Guidelines for management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction in individuals with central neurological conditions

- Spinal cord injury bowel management

- Unity Health Toronto. Digital stimulation (rectal touches)

- Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence (SCIRE). Bowel dysfunction and management following spinal cord injury.

- SCIRE Community. Bowel changes after spinal cord injury.

- SCIRE Community. Dietary fibre.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hughes M. Bowel management in spinal cord injury patients. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2014 Sep;27(3):113-5

- ↑ Khadour FA, Khadour YA, Xu J, Meng L, Cui L, Xu T. Effect of neurogenic bowel dysfunction symptoms on quality of life after a spinal cord injury. J Orthop Surg Res 2023; 18(458).

- ↑ Vallès M, Terré R, Guevara D, Portell E, Vidal J, Mearin F. Alteraciones de la función intestinal en pacientes con lesión medular: relación con las características neurológicas de la lesión [Bowel dysfunction in patients with spinal cord injury: relation with neurological patterns]. Med Clin (Barc). 2007 Jun 30;129(5):171-3. Spanish.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Oelofse W. Bladder and Bowel Dysfunction in Spinal Cord Injury. Plus Course 2024

- ↑ Continence Foundation of Australia. Bristol Stool Chart. Available from: https://www.continence.org.au/bristol-stool-chart (last accessed 4 February 2024).

- ↑ Kurze I, Geng V, Böthig R. Guideline for the management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction in spinal cord injury/disease. Spinal Cord. 2022 May;60(5):435-443.

- ↑ Coggrave M, Mills P, Willms R, Eng JJ. Bowel dysfunction and management following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence (SCIRE); 2014. 48 p. Report Version 5.0.

- ↑ Rehab and Revive. How to Massage Out Your Stuck Poop | FIX CONSTIPATION. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kqWEwOPXfOI [last accessed 20/01/2024]

- ↑ Christensen P, Bazzocchi G, Coggrave M, Abel R, Hultling C, Krogh K, Media S, Laurberg S. A randomized, controlled trial of transanal irrigation versus conservative bowel management in spinal cord-injured patients. Gastroenterology. 2006 Sep;131(3):738-47.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bølling Hansen R, Staun M, Kalhauge A, Langholz E, Biering-Sørensen F. Bowel function and quality of life after colostomy in individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016 May;39(3):281-9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Waddell O, McCombie A, Frizelle F. Colostomy and quality of life after spinal cord injury: systematic review. BJS Open. 2020 Aug 27;4(6):1054–61.

- ↑ Nelson A, Ahmed S, Harrow J, Fitzgerald S, Sanchez-Anguiano A, Gavin-Dreschnack D. Fall-related fractures in persons with spinal cord impairment: a descriptive analysis. SCI Nurs. 2003 Spring;20(1):30-7.

- ↑ Slater W. Management of faecal incontinence of a patient with spinal cord injury. Br J Nurs. 2003 Jun 26-Jul 9;12(12):727-34.