Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis and Back Pain

Aims[edit | edit source]

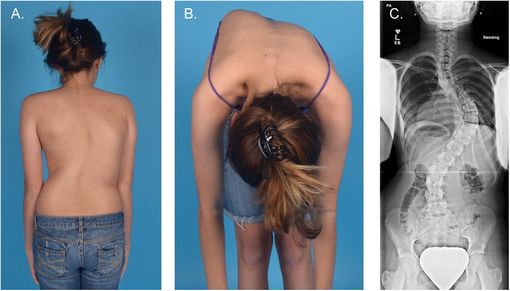

This article aims to discuss the relationship between adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) (fig. 1) and back pain, and the management plan for it.

Objectives[edit | edit source]

- To introduce AIS

- To discuss the relationship between AIS and back pain, with considering of dysfunctional breathing

- To discuss the potential treatments for back pain in AIS

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Scoliosis is where the spine twists and curves to the side (National Health Service (NHS), 2017). See Scoliosis for full details.

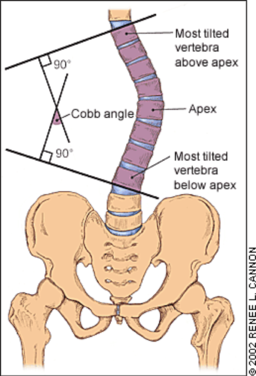

The common outcome measure for the curvature of scoliosis is the Cobb angle (fig.2).

One type of idiopathic scoliosis is AIS.

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

AIS is a common disease with an overall prevalence of 0.47-5.2 % in the current literature (Konieczny et al., 2013). It develops at the age of 11-18 and takes up 90% of idiopathic scoliosis cases in children (Konieczny et al., 2013). The female to male ratio ranges from 1.5:1 to 3:1 and increases substantially with increasing age (Konieczny et al., 2013). Genetic factors play a role as well (Konieczny et al., 2013).

Back pain in AIS[edit | edit source]

Back pain is approximately twice as prevalent in patients with AIS compared to non-scoliosis patients (Théroux et al., 2015; Sato et al., 2011; Joncas et al., 1996).

Théroux et al (2015), Sato et al (2011) and Joncas et al (1996) reported that back pain most commonly occurred in the lumbar region followed by the thoracic region in AIS for both sexes. A statistically significant association was found between thoracic pain and thoracic scoliosis in patients with AIS as well (Théroux et al, 2015). Most AIS patients with back pain reported their pain as moderate (Théroux et al., 2015; Joncas et al., 1996) to mild (Sato et al, 2011) intensity. Sato et al. (2011) also reported that back pain in AIS lasted longer and occurred more frequently when compared to patients without scoliosis.

Back pain and Cobb angle[edit | edit source]

No statistically significant relationship was observed between pain intensity and Cobb angle severity (Théroux et al, 2015; Balagué et al., 2016). Rigo (2010) also suggested the idea that Cobb angle does not correlate with back pain. However, this paper also suggested that patients without pain tend to present smaller curves and the incidence and intensity of back pain was higher in more severe curves (> 40°-45°). The Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) (no date) suggested that the presence of back pain may due to reduced abdominal and back strength or hamstring flexibility. However, no evidence supports this statement.

Back pain and quality of life (QoL)[edit | edit source]

Makino et al. (2015) reported that low back pain (LBP) in AIS patients can cause deterioration of patients’ quality of life. Patients' self-image such as attitude their own physical appearance is one of the contributing factors (Makino et al., 2015).

Dysfunctional breathing in AIS and back pain[edit | edit source]

Dysfunctional and asymmetrical breathing pattern often presents in patients with scoliosis (Weiss et al., 2016). Trunk rotation is increased as a result of breathing forces being directed downwards to the convexity of the spinal curvature (Weiss et al., 2016). There is also a linkage between dysfunctional breathing and LBP (Chaitow, 2014; Kiesel et al., 2017) and neck pain (Kiesel et al., 2017).

Treatment[edit | edit source]

This section will cover the direct or indirect conservative and surgical treatment for back pain in AIS.

Conservative treatment[edit | edit source]

Schroth method[edit | edit source]

The Schroth method is a set of exercises which is specifically designed for patients with scoliosis, especially for idiopathic scoliosis (Berdishevsky et al., 2016). It is developed by Katharina Schroth in Germany (Kim et al., 2017).

Schroth method aims at preventing curve progression before the end of growth with the following goals:

- Proactive spinal corrections to avoid surgery

- Postural training to avoid or decelerate progression

- Information to support a decision-making process

- Teaching a home-exercise program

- Support help for self-help

- Prevention and coping strategies for pain

(Berdishevsky et al., 2016)

Evidence for the effectiveness of Schroth method exercises[edit | edit source]

Schreiber et al. (2015)

Schreiber et al. (2015) did a randomised controlled trial (RCT) which suggested that Schroth method exercises with standard of care improved pain in patients with AIS over a 6-month intervention. Table 1 shows the participants, intervention, comparison, outcomes (PICO) model of the study.

| Participants | Intervention |

50 patients

|

25 patients

|

| Comparison | Outcomes |

25 patients

|

Collected at baseline, 3 and 6 months

|

* SRS-22r is a scoliosis-related QoL questionnaire that assesses five domains: function, pain, self-image, mental and satisfaction with care. Each question is scored from 1 to 5, where 1 is the worst, and 5 the best.

Results

- SRS-22r pain score difference between the two groups from baseline to 3 months was not statistically significant: -29.16; p=0.45

- Schroth group has significant improvement in SRS-22r pain score from 3 to 6 months when compared to the control group: 85.25; p=0.02

Table 2 shows the results of the study.

| Intervention group (n=25) | Control group (n=25) | 0 to 3 months difference in change between group | 3 to 6 months difference in change between groups | |||

| Mean | Standard errors | Mean | Standard errors | p-value | p-value | |

| SRS-22r pain: baseline | 422.84 | 31.53 | 348.63 | 31.36 | 0.45 | - |

| SRS-22r pain: 3 month | 460.76 | 32.37 | 415.71 | 32.62 | 0.02 | |

| SRS-22r pain: 6 month | 525.99 | 33.38 | 395.68 | 32.36 | - | |

Strengths

- The assessors and the statistician were blinded to the treatment allocation

- Standardised treatment by developing the classification and exercise prescription algorithms

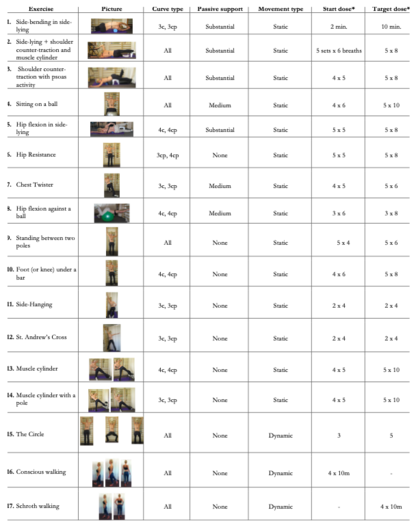

- Specific exercise prescription for each curve type (fig. 3)

Limitations

- Only overall pain was measured

- The therapists, patients and accessors could not be blinded to the exercises in which they were involved

- Pain is a subjective outcome

- RCT is not at the top of the hierarchy of evidence

Lee et al. (2016)

Lee et al. (2016) did a case study which showed a decrease in pain and Cobb’s angle in all subjects after applying the Schroth method with emphasis on active holding. Table 3 shows the PICO model of the study and table 4 shows the results of it.

| Participants | Intervention |

|---|---|

3 patients

|

3 patients

|

| Comparison | Outcomes |

| Patients baseline before intervention |

|

| Subject no. | Subject characteristics | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | Cobb angle | ||||

| Pre-test | post-test | Pre-test | post-test | ||

| 1 |

|

4 | 0 | 20° | 10.8° |

| 2 |

|

8 | 0 | 20.3° | 4° |

| 3 |

|

8 | 3 | 30.6° | 18.5° |

Limitations

- A very small sample size

- Case study is not considered as the “best evidence” as it is low in terms of level of evidence

- No detailed description about the Schroth method program with emphasis of active holding

- Participants presented with different pain and underlying conditions

- Long term effects were not measured, the benefits might be temporary

- Not addressing directly to AIS patient, patients were all over 18

Breathing retraining and exercises[edit | edit source]

There are evidence suggesting the use of breathing exercises as a treatment for chronic low back pain (Anderson et al., 2017). This review included 3 RCTs of medium quality with reference to the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale (Liao et al., 2018). The searches were conducted across 5 databases and 10 years (2005-2015). However, one thing to note is that the patients included in the studies may not have scoliosis.

Rotational Angular Breathing (RAB)[edit | edit source]

Schroth method is considered to be more effective than manual treatments because of its three-dimensional nature and its rotational angular breathing (RAB) component (Kim et al., 2017). It ‘helps in vertebral and rib cage derotation and in increasing vital capacity’ (Berdishevsky et al., 2016).

RAB helps expand the ribcage by pushing the ribs ‘sideways and backwards’ and helps return the vertebrae closer to their normal, untwisted position (Berdishevsky et al., 2016) (fig. 4).