Neck and Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders

Introduction:[edit | edit source]

A dysfunctional breathing pattern is defined as “inappropriate breathing that is persistent enough to cause symptoms with no organic cause” (Bradley and Esformes, 2014). Normal breathing involves synchronised upper rib cage and lower rib cage movement as well as activation of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles. Abnormal breathing, also known as thoracic breathing” instead involves breathing from the upper chest with greater upper rib cage motion compared to lower rib cage. Thoracic breathing is produced by recruiting the accessory muscles of respiration (including upper trapezius, sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles) rather than abdominal motion. A cross-sectional study by Deshmunk et al (2022) found that 74% of participants complaining of back pain and 68% of those complaining of neck pain presented with a dysfunctional breathing pattern. Individuals with poor posture, scapular dyskinesis, low back pain and neck pain have also been shown to exhibit faulty breathing mechanics, suggesting a link between spinal mechanics and dysfunctional breathing.

There is evidence suggesting a relationship between lower back pain and respiration. The diaphragm is a key driver of the respiratory pump and attaches onto the lower six ribs, xiphoid process and the lumbar vertebral column. Hodges et al (2007) stated that as the diaphragm has an important role in both postural and breathing functions, disruption in one could negatively affect the other. A systematic review (Beeckmans et al, 2016) found a significant correlation between lower back pain and dysfunctional breathing including both pulmonary pathology and non-specific breathing pattern disorders. Furthermore, a case-control study (Roussel et al, 2009) observing patients with chronic lower back pain found significantly more altered breathing patterns during performance of motor testing.

Spinal stability and respiration use similar muscles to function and there is a need for a stabilised cervical and thoracic spine to assist movement of the ribs during inspiration and expiration. Spinal stability is derived from co-contraction of the abdominal muscles which increases the intra-abdominal pressure (Park, Kueon and Hong, 2015). Spinal instability could cause mechanical alterations leading to insufficient respiratory function and the activation of accessory muscles, producing a dysfunctional breathing pattern. A systematic review (Kahlaee, Ghamkhar and Arab, 2017) including 68 studies found a significantly lower maximum inspiration and expiration pressures in patients with chronic neck pain compared to asymptomatic patients. Muscle strength and endurance, cervical range of motion and lower Pco2 were found to be significantly correlated to reduced chest expansion and neck pain. The study concluded breathing re-education to be effective in improving come cervical musculoskeletal impairment and breathing pattern disorders.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The thoracic cage is inclusive of the spine, ribs, and the adjacent muscles. The anatomy at this area is important to ensure effective inspiration and expiration in the functional breathing process. Primary inspiratory muscles are the diaphragm and external intercostals, to help elevate the ribs and sternum, with a ‘bucket handle’ rib motion. Expiration is usually a passive process, with additional muscles such as the internal intercostals, and abdominal muscles, making this forceful if required.

The muscles of the diaphragm are directly connected to the spine, via the lower six ribs and their costal cartilage, upper three lumbar vertebrae as right crus, and upper two lumbar vertebrae as left crus, separating the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. The intercostal muscles are located between ribs to aid expansion of the thoracic cage on inspiration.

Accessory muscles aid these original breathing mechanics when additional power is needed to generate larger, deeper breaths. These often include the sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, and trapezius, however any muscle attached to the upper limb and thoracic cage can act as an accessory muscle for inspiration.

Differential diagnoses[edit | edit source]

Neck pain (cervical spine)

| Neck Pain without radiculopathy | Neck pain with radiculopathy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-specific neck pain | Abscess | ||

| Acute disc prolapse | Anterior interosseous nerve entrapment | ||

| Acute torticollis | Arteriovenous malformation | ||

| Acute trauma (e.g. Whiplash) | Carpal tunnel syndrome | ||

| Adverse drug reactions | Cubital tunnel syndrome | ||

| Osteoarthritis of the cervical spine | Herpes zoster | ||

| Inflammatory arthritis | Parsonage-Turner syndrome (brachial plexopathy) | ||

| Cervical strain | Posterior interosseus nerve entrapment | ||

| Cervical fracture or dislocation | Radial tunnel syndrome | ||

| Cervical radiculopathy | Reflex sympathetic dystrophy | ||

| Fibromyalgia | Rotator cuff tendinosis | ||

| Infection | Thoracic outlet syndrome | ||

| Malignancy | |||

| Carotid or vertebral artery dissection | |||

| Neurological disorders leading to dystonia | |||

| Psychogenic dystonia |

Thoracic spine pain

| Thoracic pain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Costochondritis | |||

| Lower rib pain syndrome | |||

| Sternalis syndrome | |||

| Thoracic costovertebral joint dysfunction | |||

| Fibromyalgia | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |||

| Axial spondyloarthropathy | |||

| Psoriatic arthritis | |||

| Osteoporotic fracture | |||

| Neoplasm with pathological fracture or bone pain |

Lower back pain (lumbar spine)

| Lower back pain without radiculopathy | Lower back pain with radiculopathy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological: | metastatic neoplasm | ||

| Sciatica | Acute cholecystitis | ||

| Myelopathy or a higher cord lesion | Cardiac or pulmonary disease | ||

| Peroneal palsy or other neuropathies | Pancreatitis | ||

| Deep gluteal syndrome/Piriformis syndrome | Pelvic inflammatory disease | ||

| Spinal stenosis | Pelvic mass | ||

| Systemic: | Prostatitis | ||

| Sacroiliitis in spondyloarthropathies | Pyelonephritis | ||

| Vascular claudication | |||

| Other: | |||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | |||

| Aseptic necrosis of femoral head | |||

| Facet joint arthropathy | |||

| Greater trochanteric pain | |||

| Intra-abdominal pathology | |||

| Osteoarthritis of the spine or hip | |||

| Osteoporosis | |||

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |||

| Shingles (Herpes zoster) |

Red flag conditions[edit | edit source]

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Triage[edit | edit source]

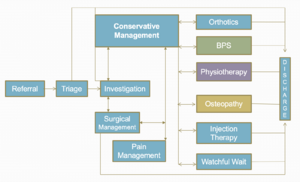

Triaging patients is vital to ensure the appropriate management strategy is selected. Decision-making and problem solving needs to occur, following an initial assessment which identifies the patient’s pain pattern, to then categorise the correct treatment for each individual patient (Hall, 2014). Discussed above are the Red Flags and conditions that you need to be aware of during this stage, as safety is of paramount importance.

The Patient's Perspective[edit | edit source]

As the clinician you may choose to ask an open question regarding the patient’s understanding about why they may be attending the appointment today, to listen actively to the patient’s story, and noticing evidence and reasoning for physical illness and emotional distress (Gask and Usherwood, 2002). This can address the dual focus where patients usually have a combination of both and are not exclusively physically ill.

It also gives the patient an opportunity to consider their understanding, feelings, coping strategies, attitude to physical activity, beliefs, expectations, and goals regarding their experience with their pain (Jones and Rivett, 2004). The clinician can then start to consider appropriate management strategies to support these perspectives using collaborative clinical reasoning and inform these beliefs using education techniques.

The use of open questions should be predominantly used to ensure these collaborative goals are met, as the clinician can appropriately identify where education may be required (Petty, 2018). If the clinician picks up on any information that may not be realistic or helpful, this can be addressed at a later stage with the patient.

Social History[edit | edit source]

It is important to ask the patient about their employment status, home situation, and any leisure activities the patient enjoys, to know their responsibilities and what they need to be able to achieve on a functional level, for goal setting to be appropriate.

Body Chart and Pain Recognition[edit | edit source]

This is a method often used to help highlight the exact area and type of symptoms being experienced by the patient. This can help focus questioning and pattern recognition in relation to diagnoses (Petty, 2018). You can mark each area to distinguish symptoms differently, but also how they may link together. The quality of the pain can also be determined here, including encouraging the patient to ‘describe the pain’ to provide an insight into the physiological mechanism.

This can help determine whether the pain is of nociceptive, peripheral neuropathic, central sensitisation, or autonomic origin, identifying pain intensity, referred pain, abnormal sensation, regularity and behaviour of symptoms, including 24 hour patterns, and aggravating and easing factors.

Special Questions[edit | edit source]

Red Flags for Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

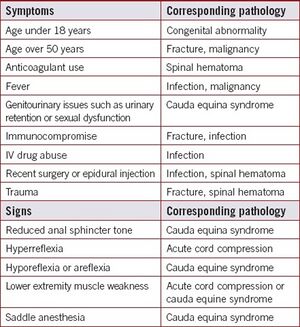

It is important to consider serious spinal conditions during any assessment of back pain. The red flags listed below may flag your attention to spinal conditions listed below that may warrant urgent, further investigation (DePalma, 2020).

Other flags[edit | edit source]

It is important to consider and screen for alternative flags (yellow, orange, blue and black) which may interfere with physiotherapy management.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

There are various outcome measures used in low back pain, often questionnaire based to account for patient beliefs as well as functional impact of low back pain (). One of the most used tools is the Roland Morris disability questionnaire, as this has been found to reveal substantial burden of chronic low back pain on functional tasks including walking, stairs, and chores (Burbridge et al., 2020). Other studies have been evaluated for their responsiveness to determine which would best measure clinically meaningful change in this population, including Oswestry disability index, patient specific functional scale (PSFS), and the pain self-efficacy questionnaire (PSEQ). The PSFS and PSEQ were found to be more responsive following participation in a back class programme suggesting these may be the most appropriate to measure real change after these interventions (Maughan and Lewis, 2010).

- Patient specific functional scale

- Fear-Avoidance Belief Questionnaire

- STarT Back Screening Tool

- The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire

- Pain self-efficacy questionnaire

- Oswestry Disability Index

Investigations[edit | edit source]

Has the patient had any other investigations such as blood tests or radiology (x-ray, MRI, CT, ultrasound)?

Has the patient had any operations/procedures carried out for a similar condition or presentation in the past? What was the treatment given for this i.e., have they had physiotherapy interventions prior to this.

Low Back Pain assessment[edit | edit source]

The NICE guidelines for low back pain and sciatica highlight the importance of considering alternative diagnoses, and if they are suspected refer on accordingly (NICE, 2016). As well as clearing serious pathology during both the subjective questioning and objective testing, clinicians must clear lower limb pathologies due to the likelihood of the lumbar spine referring symptoms to that joint too.

Observation[edit | edit source]

Movement patterns[edit | edit source]

- Gait and sit to stand- observe the patient from the very start!! How do they stand from the chair in the waiting room? How do they walk into the consultation room? Do they have an antalgic or Trendelenburg gait pattern?

- How are they sat in the chair; do they sit comfortably?

Posture and alignment[edit | edit source]

- Scoliosis

- Lordosis

- Kyphosis

Assess in sitting and standing to see if positioning has an impact on this.

Other observations[edit | edit source]

- Body type

- Attitude and beliefs

- Facial expressions

- Skin

- Hair

- Leg length discrepancy

Functional tests[edit | edit source]

1. Assess the movement they report struggling with the most.

2. For back pain, a squat test can highlight other lower limb pathologies, however if this is negative you do not need to test peripheral joints in lying. These have been shown to be reliable tests that can differentiate between overall strength ability of patients too (Drake, Kennedy and Wallace, 2017).

Always relate the functional testing to their ability, and goals aiming towards the activities they want to get back to achieving.

Movement testing[edit | edit source]

- Active range of motion (AROM)

- Passive range of motion (PROM) /overpressure

- Muscle strength testing (resisted isometrics in flexion, extension, side flexion, rotation, and testing core stability and functional strength tests)

Movement control testing[edit | edit source]

There are six motor control tests that can be used to identify reduced movement control and poor lumbar movement control, which are discussed in detail here. A significant difference was found in a study by Luomajoki et al (2008) with patients with low back pain and subjects without back pain regarding their ability to actively control movements in the low back.

Neurological assessment[edit | edit source]

See low back pain neurological assessment.

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Reliability of manual palpation in the assessment of low back pain varies greatly, and the validity of these tests are commonly used by manual therapists and clinicians (Nolet et al., 2021). However, these tests can give some insight into a patient’s affected lumbar segmental level.

Special tests[edit | edit source]

See lumbar assessment here for more details.

Psychosocial assessment[edit | edit source]

See here for psychosocial approach to treatment.

Neck pain assessment[edit | edit source]

Subjective assessment

Take a detailed history around the neck pain. Some areas to explore include:

- Onset of the pain- acute/chronic/recurring/sudden/related to trauma or a particular activity.

- Nature and location of the pain- any radiation.

- Pain severity

- Occupational and social history.

- Medical and drug history.

- Symptoms of anxiety or depression.

- Previous injury or infection.

- Presence of fever.

- History of cancer.

- Presence of symptoms of spinal cord compression- lower limb weakness or altered sensation, disturbance of bowel or bladder function.

Objective

Conduct a physical examination to explore the potential causes of the neck pain further:

- Clear the shoulder and thoracic spine.

- Assess the appearance of the neck, including posture.

- Inspect the skin (e.g. for rashes or bruising)

- Assess range of motion- flexion, extension, side flexion, rotation.

- Palpate the neck for tenderness (Significant specific bony tenderness or midline tenderness is suggestive of other pathology).

- Check for cervical lymphadenopathy (could suggest infection, malignancy or an inflammatory cause)

- Assess deep neck flexor muscle strength

Perform a neurological examination:

- Myotomes (power).

- Tone.

- Reflexes.

- Dermatomes (sensation).

Special tests for cervical radiculopathy

A combination of special tests can be used to help identify cervical radiculopathy:

- The spurlings test

- Arm squeeze test

- Axial traction

- Upper limb neurodynamic tests

Imaging

Cervical X-rays and other imaging/investigations are not routinely required. However, MRI is indicated in people with complex cervical radiculopathy, for example if there is reason to suspect myelopathy/abscess, progressively worsening objective neurological findings or failure to improve after 4-6 weeks of conservative treatment.

‘Bringing the two together’ – Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders interventions.[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

See here for information on medical management for low back pain and breathing pattern disorders.

Physical Interventions[edit | edit source]

Normal breathing mechanics play a key role in posture and spinal stabilisation, and breathing pattern disorders can contribute to pain and motor control deficits (Bradley and Esformes, 2014). This study showed that even healthy individuals who exhibited biochemical and biomechanical signs of breathing pattern disorders were significantly more likely to score poorly on the Functional Movement Screen, despite any pain being experienced by the patient.

The results of one study have highlighted the importance of diaphragmatic breathing to reduce implications on muscular imbalances, motor control alterations and physiological adaptations (Bradley and Esformes, 2014).

One study suggests diaphragm and transverse abdominis are key features in provision of core stability, but there is a reduction of support given to the spine, by the muscles of the torso, if there is both a load challenge to the low back combined with a breathing challenge (Chaitow, 2004).

A randomised controlled trial concluded that breath therapy was favoured during at six-eight weeks, and physical therapy was favoured at six months, however overall changes in measures of pain and disability with back pain were comparable to those from physical therapy (Mehling et al., 2005).

Additionally, one study found that in a group of patients with varying degrees of low back pain, motor control activities created altered breathing patterns in around 71% of these (Ostwal and Wani, 2014). This correlates with data gained by Chaitow (2004), where they concluded the transverse abdominis and diaphragm are key providers in core stability and respiration, and the coordination of these 2 roles may be complicated when the demand of one task increases. This matches the results by Ostwal and Wani (2014), where the biggest change in breathing patterns was found during the knee bend fall out test at 91% patients had altered patterns.

Due to this variety of evidence supporting the need for optimal function of the transverse abdominis and diaphragm function in trunk stability and normal breathing mechanics, it is important to identify these in clinic and target exercises towards the breathing pattern disorder as well as the symptoms from the low back pain.

In relation to treatment, many interventions have certain principles in common (CliftonSmith and Rowley, 2011).

1. Education on the pathophysiology of the disorder

2. Self-observation of one’s own breathing pattern

3. Restoration to a basic physiological breathing pattern: relaxed, rhythmical nose-abdominal breathing

4. Appropriate tidal volume

5. Education of stress and tension in the body

6. Posture

7. Breathing with movement and activity

8. Clothing awareness

9. Breathing and speech

10. Breathing and nutrition

11. Breathing and sleep

12. Breathing through an acute episode

Breathing exercises[edit | edit source]

Breathing programmes have been shown to be effective in patients with chronic low back pain, and have been able to reduce pain, improve respiratory function, and/or health related quality of life (Anderson and Huxel Bliven, 2017).

Breathing control: (NHS University Hospital Southampton, 2023).[edit | edit source]

To breathe in a more natural way, encourage your patient to sit in a comfortable armchair or lie on the bed, and release any tension in your neck and shoulders. Place on hand on your chest, and one on top of your tummy. Focus on directing air to the stomach, to use your diaphragm more effectively.

Keep a normal breath rate and size whilst practicing this.

When the patient has been able to replicate diaphragmatic breathing in lying, progress to encouraging to check their pattern of breathing when walking, maintaining nose breathing.

Breathing through a balloon: (Smale, 2018).[edit | edit source]

90-90 Hip Lift with Balloon- Video outlining the below instructions:

1. Encourage the patient to adopt a 90-90 hip lift.

2. Get patient to put their tongue on the roof of their mouth and breath in through their nose.

3. On the breath out get them to lift their pelvis so their back is flat on the bed.

4. Place tongue back on the roof of the mouth and breath in through nose again.

5. Place balloon to lips and breath out into the balloon. Hold for 3-4 seconds without squeezing neck of balloon.

6. Repeat step 4-5 three times and then breath out and relax.

This can help patients retrain their zone of apposition to synchronise their diaphragm and abdominal wall. Integrating these breathing exercises with the following core strengthening exercises should be beneficial for patients with low back pain and breathing pattern disorders.

Low Back Pain and Breathing Pattern Disorders Interventions[edit | edit source]

To strength the appropriate muscles such as transverse abdominis, gym ball exercises have been shown to have a significant impact on biomechanical changes, respiratory variables, and joint position sense in participants with low back pain (Lim, 2020).

These exercises may include:

- Side bridging

- Gym ball partial curl ups

- Supine bridging with single leg raise

- Gym ball push ups

- Gym ball single leg holds

- Gym ball roll outs with an unstable support

These above exercises all increase lumbar spine stability and increase abdominal activity.

Other abdominal training exercises that may help relieve back pain may consist of:

- Bird dog/superman exercises

- Glute bridges

- Squats

- Plank exercise

- Dead bug exercises

- Knee rolls (to either side)

- Cat-cow positions

Other considerations (NHS University Hospital Southampton)[edit | edit source]

- Lifestyle changes- slow down and set realistic goals. Encourage pacing and energy conservation.

- Speech- continue to use abdominal, low-chest breathing pattern, take a relaxed breath out before starting to talk and breath softly through the nose.

- Sleeping- follow a relaxing night-time routine, reduce stress levels, avoid caffeinated drinks, daytime napping, and late and spicy meal at night.

- Relaxation- visualisation of a pleasant situation, body awareness exercises

Management for patients with linked neck pain and dysfunctional breathing[edit | edit source]

It is worth including elements of usual care for neck pain in the management of patients with a combination of neck pain and dysfunctional breathing in order to ensure the problem is tackled from all angles.

This management includes:

- Reassurance - neck pain is a common problem that usually resolves within a few weeks.

- Advice and education- around pillows for sleeping, return to activity and normal lifestyle, driving, speaking to GP/pharmacist around pain medication and discourage use of cervical collars.

- Physiotherapy exercises- strengthening, stretching, range of motion, manual therapy and advice on participation in regular exercise (e.g. Pilates or yoga).

- Consider referral for psychological therapy if there are psychological symptoms or risk factors.

- Consider referral to occupational health if pain is related to work.

- Consider referral to pain clinic if the person has had neck pain for more than 12 weeks and is not improving with treatment.

Additional management techniques for people with a combination of neck pain and dysfunctional breathing should be used.

Breathing re-education, cervical stabilisation exercises, stretching exercises incorporating slow deep breaths, breathing retraining alongside manual therapy.