Overview of Prostate Cancer

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Prostate cancer affects the prostate gland, which is part of the male reproductive system and functions to create seminal fluid.

- In 2020, there were an estimated 1.4 million new cases of prostate cancer and 375,000 prostate cancer related deaths worldwide[1]

- Prostate cancer was the second most frequent cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer death among men[1]

- It was the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men in over one-half of the countries of the world[1]

- Differences in prostate cancer diagnostic practices are most likely the greatest contributor to the worldwide variation in prostate cancer incidence rates[1]

- The majority of men diagnosed with prostate cancer have a slow growing variation of the disease that is nonthreatening to their natural life expectancy and can be safely monitored without need for medical intervention[2]

- For those men diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer, only 28% will survive beyond five years of diagnosis[2]

- The prognosis worsens if the cancer has a chance to spread, metastasis rapidly involves the lymphatic system, lungs, bone marrow, liver or adrenal glands[2]

The treatment of prostate cancer is a common entryway into the speciality area of men's health physiotherapy because these patients can be effectively treated without competency in the full scope of men's health skills such as the internal examination and use of real-time ultrasound.[3] Please follow these links to learn more about physiotherapy assessment and treatment of men's health conditions.

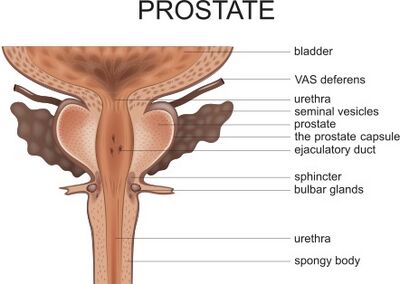

Anatomy Review[edit | edit source]

- The prostate is a gland located immediately below the internal urethral sphincter and surrounds the commencement of the urethra. The external urethral sphincter is immediately below the prostate. It is situated in the pelvic cavity: below the lower part of the symphysis pubis, above the superior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm, and in front of the rectum. It can be palpated, especially when enlarged.[4] It is about the size of a walnut.[3]

- The prostate is perforated by both the urethra and the ejaculatory ducts. The ejaculatory ducts open into the prostatic portion of the urethra.[4]

- Arterial supply: internal pudendal, inferior vesical, and middle hemorrhoidal.[4]

- Innervation: receives sympathetic input via the hypogastric nerve and parasympathetic input via the pelvic nerve. The hypogastric and pelvic nerves also provide sensory inputs to the gland.[5]

- The prostate gland is divided into three anatomical lobes: two anterior and one median[2]

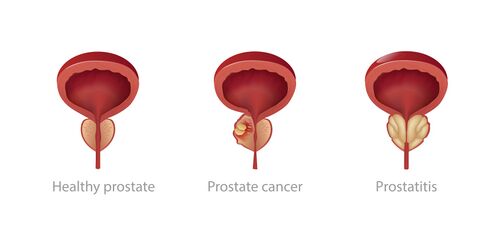

- Knowing the anatomy of the prostate is central to the understanding of both benign and malignant prostatic pathologies. This is because the area of the prostate the pathology originates is a defining characteristic of each of the three main prostate diseases. The three main diseases of the prostate are:[2]

- Benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH)

- Prostate cancer

- Chronic prostatitis

- Knowing the anatomy of the prostate is central to the understanding of both benign and malignant prostatic pathologies. This is because the area of the prostate the pathology originates is a defining characteristic of each of the three main prostate diseases. The three main diseases of the prostate are:[2]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Early prostate cancer may be asymptomatic, routine screenings of prostate cancer are commonly being done on asymptomatic men.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms:

- Difficulty starting urination

- Weak or interrupted flow of urine

- Frequent urination, especially at night

- Difficulty emptying the bladder completely

- Pain or burning during urination

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Pain in the back, hips, or pelvis that doesn’t go away

- Painful ejaculation or orgasm[3]

It is important to note that these signs and symptoms may also be present with other noncancerous prostate-related disease conditions such as BPH or prostatitis. If a patient presents with the above symptoms, referral to a medical doctor or urologist is urgently recommended for proper diagnosis.

Cancer is one condition that can affect the prostate and cause enlargement of the gland. When the prostate enlarges, it can compress the urethra and cause difficulties with urine flow. An enlarged prostate is not always lead to a diagnosis of prostate cancer, rather that further testing in indicated for proper differential diagnosis.[3]

If a patient reports symptoms of sexual dysfunction, it is important to ask about the timeline of their issues. It is of greater concern if the sexual dysfunction issue involves orgasm and ejaculation, and have occurred within the previous few months. A referral should be made for differential diagnosis.[3]

Tumor Staging[edit | edit source]

- The diagnosis of prostate cancer is established via a biopsy of the prostate gland

- A small piece of the prostate gland is removed and examined under a microscope for cancer cells. If cancer cells are found then a Gleason score will be determined from the biopsy. A Gleason score indicates how likely the cancer is to spread. It ranges from 2–10, the lower the score the less likely it is that cancer will spread

- False-negative results often occur; therefore, multiple biopsies may be done before prostate cancer can be detected and confirmed

Stage I: Cancer cannot be felt during a digital rectal exam, but it may be found during surgery being done for another reason. Cancer has not yet spread to other areas.

Stage II: Cancer can be felt during a digital rectal exam or discovered during a biopsy. Cancer has not yet spread.

Stage III :Cancer has spread to nearby tissue

Stage IV: Cancer has spread to lymph nodes or to other parts of the body

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

While the prevalence of prostate cancer is common, relatively little is known about its etiology.[1] There are several known risk factors that have been shown to indicate an increase in the risk of developing this type of cancer.

Age

Prostate cancer is rare in men younger than 40, but the chance of having prostate cancer rises rapidly after age 50. About 6 in 10 cases of prostate cancer are found in men older than 65.

Race/ethnicity

Prostate cancer develops more often in African American men and in Caribbean men of African ancestry than in men of other races. And when it does develop in these men, they tend to be younger. Prostate cancer occurs less often in Asian American and Hispanic/Latino men than in non-Hispanic whites. The reasons for these racial and ethnic differences are not clear.

Geography

Prostate cancer is most common in North America, northwestern Europe, Australia, and on Caribbean islands. It is less common in Asia, Africa, Central America, and South America.

The reasons for this are not clear. More intensive screening for prostate cancer in some developed countries probably accounts for at least part of this difference, but other factors such as lifestyle differences (diet, etc.) are likely to be important as well. For example, Asian Americans have a lower risk of prostate cancer than white Americans, but their risk is higher than that of men of similar ethnic backgrounds living in Asia.

Family history

Prostate cancer seems to run in some families, which suggests that in some cases there may be an inherited or genetic factor. Still, most prostate cancers occur in men without a family history of it.

Having a father or brother with prostate cancer more than doubles a man’s risk of developing this disease. (The risk is higher for men who have a brother with the disease than for those who have a father with it.) The risk is much higher for men with several affected relatives, particularly if their relatives were young when the cancer was found.

Gene changes

Several inherited gene changes (mutations) seem to raise prostate cancer risk, but they probably account for only a small percentage of cases overall. For example:

- Inherited mutations of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, which are linked to an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancers in some families, can also increase prostate cancer risk in men (especially mutations in BRCA2).

- Men with Lynch syndrome (also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer,or HNPCC), a condition caused by inherited gene changes, have an increased risk for a number of cancers, including prostate cancer.

Other inherited gene changes can also raise a man’s risk of prostate cancer. For more on some of these gene changes, see What Causes Prostate Cancer?

Factors with less clear effects on prostate cancer risk

Diet

The exact role of diet in prostate cancer is not clear, but several factors have been studied.

Men who eat a lot of dairy products appear to have a slightly higher chance of getting prostate cancer.

Some studies have suggested that men who consume a lot of calcium (through food or supplements) may have a higher risk of developing prostate cancer. But most studies have not found such a link with the levels of calcium found in the average diet, and it’s important to note that calcium is known to have other important health benefits.

Obesity

Being obese (very overweight) does not seem to increase the overall risk of getting prostate cancer.

Some studies have found that obese men have a lower risk of getting a low-grade (slower growing) form of the disease, but a higher risk of getting more aggressive (faster growing) prostate cancer. The reasons for this are not clear.

Some studies have also found that obese men may be at greater risk for having more advanced prostate cancer and of dying from prostate cancer, but not all studies have found this.

Smoking

Most studies have not found a link between smoking and getting prostate cancer. Some research has linked smoking to a possible small increased risk of dying from prostate cancer, but this finding needs to be confirmed by other studies.

Chemical exposures

There is some evidence that firefighters can be exposed to chemicals that may increase their risk of prostate cancer.

A few studies have suggested a possible link between exposure to Agent Orange, a chemical used widely during the Vietnam War, and the risk of prostate cancer, although not all studies have found such a link. The National Academy of Medicine considers there to be “limited/suggestive evidence” of a link between Agent Orange exposure and prostate cancer. To learn more, see Agent Orange and Cancer.

Inflammation of the prostate

Some studies have suggested that prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate gland) may be linked to an increased risk of prostate cancer, but other studies have not found such a link. Inflammation is often seen in samples of prostate tissue that also contain cancer. The link between the two is not yet clear, and this is an active area of research.

Sexually transmitted infections

Researchers have looked to see if sexually transmitted infections (like gonorrhea or chlamydia) might increase the risk of prostate cancer, because they can lead to inflammation of the prostate. So far, studies have not agreed, and no firm conclusions have been reached.

Vasectomy

Some studies have suggested that men who have had a vasectomy (minor surgery to make men infertile) have a slightly increased risk for prostate cancer, but other studies have not found this. Research on this possible link is still under way.

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Prostate Cancer Tests and Screenings[edit | edit source]

Although PSA remains the gold-standard biomarker for PCa diagnosis and is one of the most widely used blood-based biomarkers in cancer, it contributes significantly to over-treatment of men with PCa [5]. This is a significant issue, as treatment options for PCa are associated with side effects that can have a profound negative impact on quality of life.[2]

Treatment Options[edit | edit source]

Compare pro's and con's

Side effects/expected PT symptoms

Surgical Interventions[edit | edit source]

Radiation[edit | edit source]

Active Surveillance[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

- x

or

- numbered list

- x

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021 May;71(3):209-49.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Tonry C, Finn S, Armstrong J, Pennington SR. Clinical proteomics for prostate cancer: understanding prostate cancer pathology and protein biomarkers for improved disease management. Clinical Proteomics. 2020 Dec;17(1):1-31.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Roscher, P. Men's Health. Overview of Prostate Cancer. Physioplus. 2022

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gray H. Anatomy of the human body. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1918; Bartleby. com, 2000.

- ↑ White CW, Xie JH, Ventura S. Age-related changes in the innervation of the prostate gland: implications for prostate cancer initiation and progression. Organogenesis. 2013 Jul 1;9(3):206-15.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Are the Symptoms of Prostate Cancer? Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/basic_info/symptoms.htm (accessed 14/04/2022).