Promoting Active Living in Young People Through Behaviour Change

Original Editors - Arden Metford,Ronan Mac Cann , Lee Krol, Lee Pettett, Sameena Anjum, Brian McGowan, and Iarla Byrne as part of the Queen Margaret University's Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Ronan Mac Cann, Lee Pettett, Sammy Anjum, Arden Metford, Kim Jackson, Lee Krol, Lucinda hampton, Rucha Gadgil, Rachael Lowe and Brian McGowan

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The physical and mental health behaviour of today’s adolescent generation are determinants of growth and development, now and throughout their lifespan [1] [2]. The technological advances of modern society have contributed to sedentary lifestyles, causing young people to have an increased body weight and body mass index (BMI) than one generation earlier[3].

- The gradual increase of habitual sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity seen in adolescents is a major contributor to chronic disease and is strongly correlated with the diagnosis of these diseases [4].

- Participation in all types of physical activity drops dramatically as a child's age and grade in school increase. It's important that physical activity be a regular part of family life.

- Globally, physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for mortality, causing 3.2- 5 million deaths annually [5] [6] [7].

The learning of healthy behavioural habits is vital during the adolescent years as it will assist in carrying forward this healthy active behaviour into adulthood. Behaviours of active living established in early years can provide the greatest impact on maintaining these positive habits across one’s lifespan and influence mortality and longevity [8] [9].

The Family's Role[edit | edit source]

Studies have found that lifestyles learned in childhood are much likelier to stay with a person into adulthood. If sports and physical activities are a family priority, they will provide children and parents with a strong foundation for a lifetime of health.

Exercise along with a balanced diet provides the foundation for a healthy, active life. One of the most important things parents can do is encourage healthy habits in their children early in life. [10]

Physiotherapist Input[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists have the knowledge and skills to design, plan and implement interventions aimed at increasing levels of physical activity in young people. Physiotherapists are in a good position to facilitate and guide active living behaviours in young people so that this behaviour is maintained into adulthood.

Behavioural change frameworks can be utilised for the larger young population, delivered in different community settings. The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) [11] focuses on the decision-making of the individual and is a model of intentional change. The TTM operates on the assumption that people do not change behaviors quickly and decisively but occur continuously through a cyclical process. A modified questionnaire is available to assist practitioners in identifying which stage of the TTM the young population is in. This categorisation is based upon the amounts of vigorous, moderate or walking activities performed within the last week.

- By focusing on individual factors and activities that individuals enjoy, the aim is to encourage adolescents to stay in the maintenance phase of the TTM of behaviour change, rather than regressing to other stages, thus maintaining an active, healthy lifestyle [12][13].

Educating the parents can play a key role in helping their child become more physically active. Some suggestions to give parents include

- Emphasize fun. Help your child find a sport that she enjoys. The more she enjoys the activity, the more likely she will be to continue it. Get the entire family involved. It is a great way to spend time together.

- Choose an activity that is developmentally appropriate. For example, a 7- or 8-year-old child is not ready for weight lifting or a 3-mile run, but soccer, bicycle riding, and swimming are all well great activities for kids this age.

- Plan ahead. Make sure your child has a convenient time and place to exercise.

- Provide a safe environment. Make sure your child's equipment and where they practice or play is safe. Make sure your child's clothing is comfortable and appropriate for the activity.

- Provide active toys. Young children especially need easy access to balls, jump ropes, and other active toys.

- Be a role model. Children who regularly see their parents enjoying sports and physical activity are more likely to do so themselves.

- Play with your children. Help them learn a new sport or another physical activity. Or just have fun together by going for a walk, hike, or bike ride.

- Set limits. Limit screen time, including time spent on TV, videos, computers, and video games, each day. Use the free time for more physical activities.

- Make time for exercise. Some children are so overscheduled with homework, music lessons, and other planned activities that they do not have time for exercise.

- Do not overdo activity. Exercise and physical activity should not hurt. If it becomes painful, your child should slow down or try a less vigorous activity. As with any activity, it is important not to overdo it. If exercise starts to interfere with school or other activities, talk with your child's doctor[10].

What is Active Living?[edit | edit source]

Active living is defined as a way of life that integrates physical and recreational activity into your everyday routine to encourage a healthier lifestyle [15]. These active routines include:

- Being active in outdoor parks, fitness centres

- Biking to work

- Walking to school

- Playing a recreational sport or game

- Activities of daily living

- Planned exercise sessions

Physical activity (PA) is defined as any movement carried out by a skeletal muscle that requires energy and ranges from low, moderate to vigorous PA with varying amounts of energy expenditure[16]. While sedentary behaviour is defined as an individual who engages in prolonged sitting or lying positions without much movement [17]. Common sedentary behaviours include TV viewing, video game playing, computer use (collectively termed “screen time”), driving automobiles and reading [17].

Physical Activity Guidelines[edit | edit source]

It is recommended (WHO 2020) that children and adolescents (aged 5–17 years), including those living with disability, for health benefits should do:

- At least an average of 60 min/day of moderate-to-vigorous intensity, mostly aerobic, physical activity, across the week

- Vigorous-intensity aerobic activities, as well as those that strengthen muscle and bone should be incorporated at least 3 days a week.

Few young people actually meet this recommendation. See link here Physical Activity in Young People

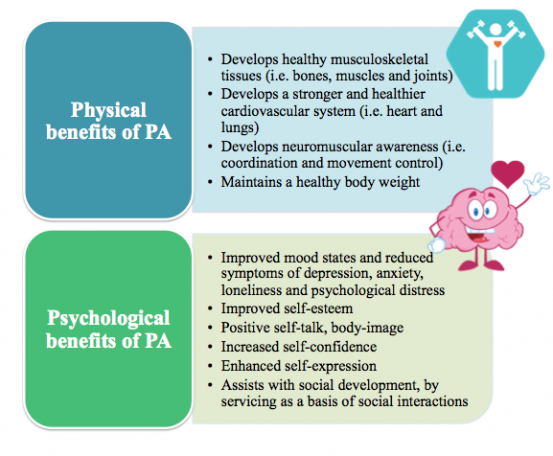

Benefits of Physical Activity in Young People[edit | edit source]

See also Physical Activity and Physical Inactivity

Justification for the Emerging Role Within Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy is delivered in a variety of settings. Traditionally physiotherapists predominantly see the most of their clientele within a clinical setting on an individual basis [22]. Good strategies and policy have been established in order to promote more active lifestyles within these settings. ‘Making Every Contact Count’ is a strategy introduced to help all organisations responsible for the health, well-being and care of the public to implement and deliver healthy messages systematically and encourage healthy lifestyles. [23]

In order to increase physical activity worldwide, it has been identified that a systems approach is required that focuses on populations and the complex interactions among the correlates of physical inactivity, rather than solely a behavioural science approach focusing on individuals [24]. The approach of going out to communities physiotherapists can guide and facilitate young people in communities to take control of their lives to reduce the risk of developing conditions later in life and therefore improving the quality of life for all individuals.

- Physiotherapists can educate clients individually and immerse themselves more widely in the community to tackle sedentary lifestyles proactively and prevent their associated co-morbidities.

- Physical education programmes at schools have been identified as an important tool to increase the awareness of health-enhancing physical activity [22]. Evidence suggests the quality of such programmes is of importance for their outcome [25].

- With extensive knowledge of promoting, guiding, prescribing and managing physical activity for young people with different needs, physiotherapists are excellent partners to develop, implement and follow-up high-quality physical education programmes in schools and community centres. This movement, additional to the individual patients seen will allow for a wider population to be targeted, which is paramount given the statistics relating to sedentary behaviour.

Facilitators to Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

There are several facilitators to physical activity and active living that can help to overcome the perceived barriers as listed below[26][27][28][29][30]:

- Valued aspects of physical activity

- Having fun and enjoying oneself

- Belonging to a sports team or group

- Afterschool program leisure activities

- Opportunities for spending time with family

- Keeping fit and health

- Mental health and well-being

- Choice of sporting opportunity

- Greater access to opportunities and facilities

- Afterschool programs to facilitate a greater level of physical activity with friends and serve as a basis of social interaction

- Proper bicycle paths and sidewalks in neighbourhoods

- Leisure Centres

Behaviour Change- Transtheoretical Model[edit | edit source]

The Transtheoretical Model (TTM), first proposed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1983) [11], is a process-oriented framework for understanding and implementing effective health behaviour change [31]. This model brings together many psychotherapy theories in one concise framework to establish a person/groups ‘readiness to change’ (Biopsychosocial) [31][32][33]. As Marcus and Forsyth (2003) [34] wrote, quite often “physical readiness is not likely to be the main barrier to activity; rather it is the psychological readiness to change”. Due to the heterogeneity of humans, many people have different readiness to change and therefore require interventions that reflect the natural cycles of health-related behaviour change. The fundamental purpose of the TTM is to systematically affect lifelong active living and it describes when and how people change [11].

The TTM encompasses over fourteen constructs [35] which several authors [36][37][38] have divided into three sections:

- Stages of Change (SOC)

- Independent variables (Processes of Change).

- Dependent variables (Decisional Balance; Self-Efficacy)

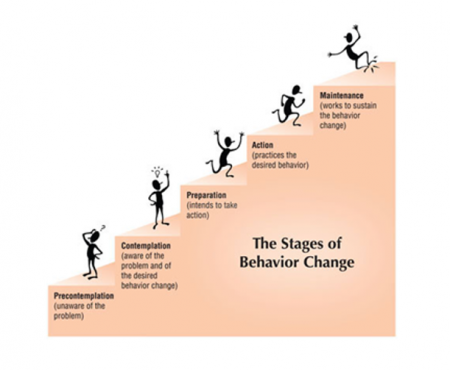

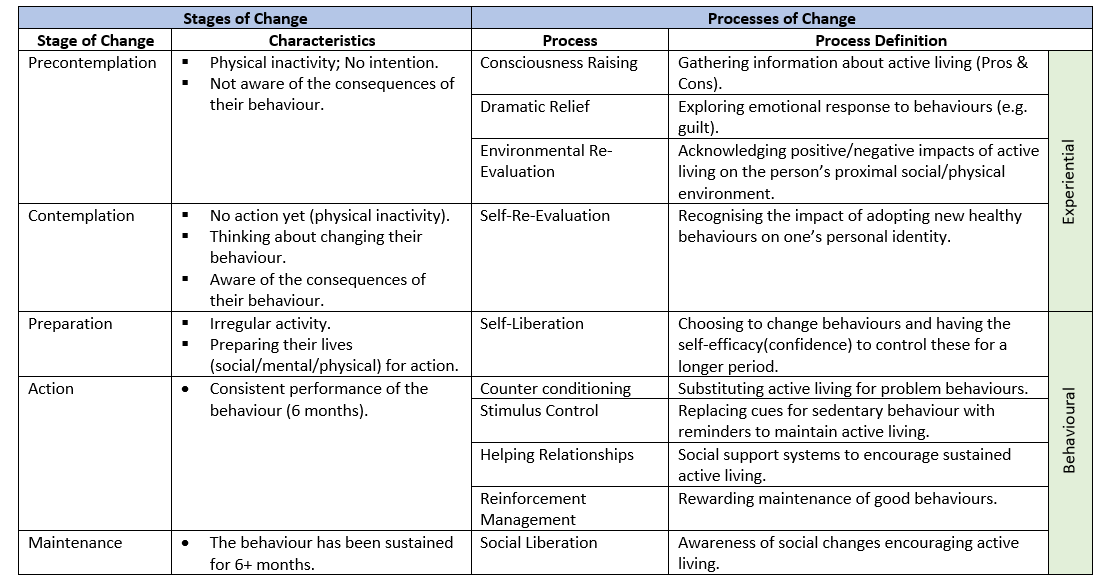

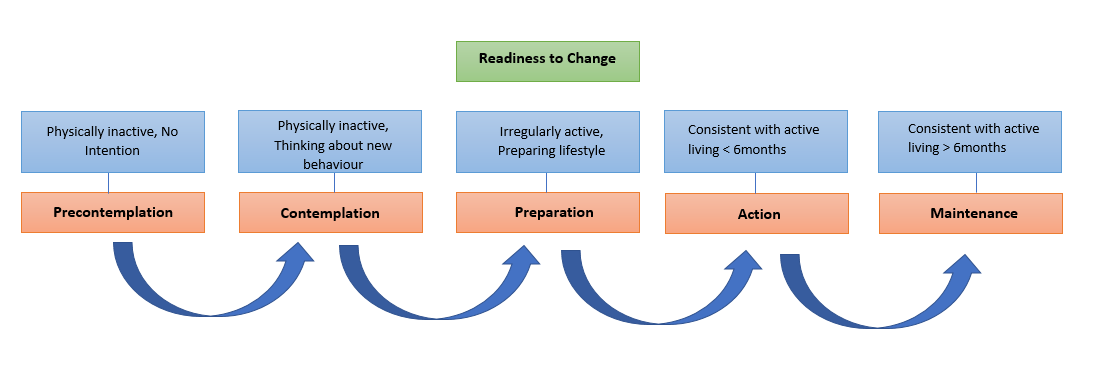

There are five stages of change in the TTM (Table 2) which categorizes people based on how active they are. In the first stage, precontemplation, individuals are not participating in any activity nor do they have any intention to change these habits. As they are unaware of the consequences of their behaviours much of the work in this stage should focus on motivational interviewing, decisional balance/self-efficacy work (education). In the contemplation stage, individuals are still not active, but they are more aware of the benefits of changing their behaviour and are beginning to think about how to change. The preparation stage involves irregular activity as the individuals begin to prepare their lives for change within the next month [39]. Once individuals are consistently active they are said to be in the action stage. It is at this point that the probability of relapse is highest and therefore it is vitally important for individuals to take advantage of any opportunities to maintain their new healthy behaviours. The final stage of the TTM is the maintenance stage and this is ultimately the end goal of an intervention. Individuals who are at this stage must be consistently performing their new behaviours for at least six months. The stages of change are often described as a cyclical process as individuals jump between stages as they progress [33].

The Processes of change are concerned with ‘how’ individuals change. [33][37] There are ten processes of change (Table 2) and the choice of the most appropriate strategy is based on the stage of change that the individuals are in. Once a SOC has been established physiotherapists can use the processes of change to design appropriate interventions/strategies for effective behaviour change. At a higher-order structure these processes are sub-divided into experiential (cognitive-affective) and behavioural processes [39]. In their study Romain and colleagues (2018) [35] propose that public health interventions should use a combination of experiential and behavioural processes of change to achieve moderate physical activity levels and sustained active living among individuals. The first five processes are experiential and are concerned with thinking about an activity/new behaviour whereas the last five are behavioural processes which involve action [40].

Modified IPAQ-SF Scoring System into the Transtheoretical Model[edit | edit source]

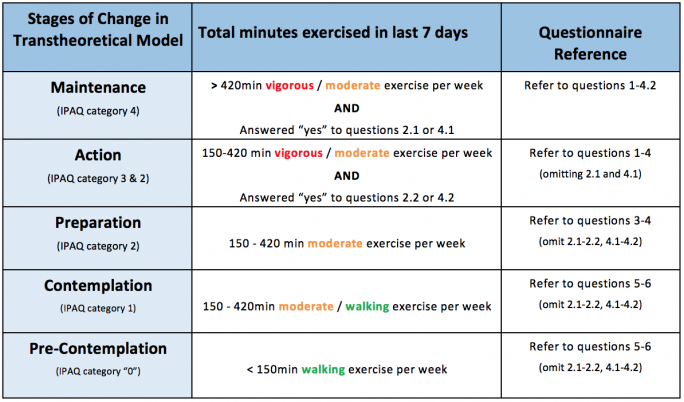

The following table depicts the marking criteria for the identification of behavioural change stages in the transtheoretical model.

Instructions on determining the stage of behaviour change:

- Calculate total number of minutes exercised in the last 7 days for vigorous, moderate and walking intensities.

- Using the table above, classify the participant into the corresponding Transtheoretical Stage of Change using the total number of minutes exercised in accordance to level of intensity.

- Please note that the participant may be placed into the “maintenance” or “action” phase if they answered yes to corresponding questions 2.1-2.2 or 4.1-4.2.

Behavioural Change Progression[edit | edit source]

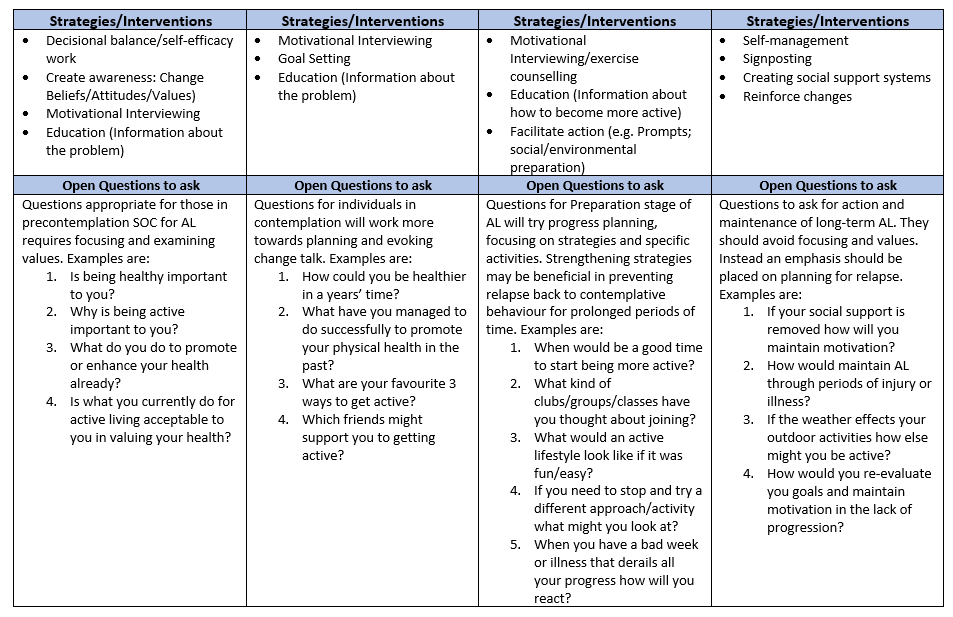

Once the physiotherapist has established at which stage the young person is at they then have to find ways to facilitate their progression through the stages to achieve the ultimate goal of sustained active living. The following figure and table give examples of strategies/interventions and open questions that can be used at each stage of the TTM to help progress onto the next stage. In the table, there is a particular focus on the open questions that can be used by physiotherapists to get young people thinking about their behaviours and how they could change. Some of the most important strategies/interventions will then be discussed in greater detail.

Strategies/Interventions to Promote Active Living[edit | edit source]

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a technique for helping people to change their desired behaviour. Physiotherapists can use MI to facilitate behaviour change processes by being empathetic, supportive and administer counselling strategies that facilitate an increase in self-efficacy and in turn result in improved feelings of accomplishment that are needed to get to and stay in the action and maintenance stages of change [41].

Empowering Young People to Maintain Active Living[edit | edit source]

Long-term adherence to health-related behaviour change is relatively poor which provides a challenge for interventions to achieve sustained active living [42]. Although a positive adherence is seen initially several authors have described a gradual decline in the maintenance of this adherence as individuals progress through the SOC [43][44]. Once adolescents have reached the action and maintenance SOC the question remains as to how we ensure that these new behaviours are sustained into adulthood? Physiotherapists can facilitate the process of health-behaviour change [45] and the empowerment of communities by providing individuals or groups with the skills and knowledge to take control of their lives and ultimately rely less on health professionals [46]. In the 2020 workforce vision for Scotland [47] it has been stated that NHS Scotland will strive to have an “integrated health and social care system that will focus on prevention, anticipation and supported self-management” [47]. With this proactive/preventative community-based approach to healthy living it is believed that the risk of developing non-communicable diseases could be prevented before adolescent’s progress into adulthood. It is therefore imperative to maintain this change with effective self-management. There are a number of strategies/interventions that can be used to initiate self-management for sustained active living in young people which include the following: self-reinforcement, relapse prevention, problem-solving skills training and the creation of good peer support systems.

Self-reinforcement involves both the intrinsic (e.g. feelings of enjoyment or achievement) and extrinsic (e.g. money) rewards of changing behaviour [48]. This positive reinforcement concept can act as a highly effective motivator for young people to stay active as they are perceived to gain something from persistence and lose something for relapsing. Realistic goal setting is often used as a method of self-reinforcement to give people a sense of achievement once the goals have been reached. Another method that can be used is self-reflection/evaluation whereby individuals critically assess how far they have come since they started their change.

Relapse prevention involves providing individuals/groups with the necessary skills to avoid “high risk” situations that have a high probability of relapse. The idea is that by providing guidance on coping strategies for lapses it is possible to revert the situation quickly before individuals relapse to old problem behaviours.

The attitudes and skills to overcome barriers to change should be thought in problem-solving sessions at all stages of behaviour change [42]. Middleton and colleagues proposed the following five skills as important to problem-solving:

- Development of positive thoughts regarding the problem behaviour and the ability to manage it.

- Recognition of the problem and its characteristics/attributes.

- Generation of alternatives (e.g. brainstorming sessions)

- Decisional balance (Pros and Cons of changing behaviour)

- Implementation of solution

A strong relationship exists between physical activity adherence and social support. It has been shown that the risk of non-adherence is twice as high in those with no social support [49]. A solution to this problem is the use of group-based interventions to create peer support systems. A large amount of research has shown the effectiveness of group-based interventions [50][42][51]. It has been suggested by Middleton and colleagues (2013) [42]that recruiting friends and family to help in health behaviour change can be beneficial for adherence. In addition, these authors proposed the idea of performing lifestyle changes in group situations to increase peer support. In her study Lindqvist (2017) examined the role physiotherapists can play in health promotion in a community setting (i.e. school) using social-cognitive theory, empowerment interventions and communication technology. In these interventions, created by the children, participants agreed to send reminders and messages of encouragement to their peers regarding physical activity and set goals. It was found that encouragement from peers was beneficial for PA adherence and that activities should cater for all likes and dislikes.

Resources[edit | edit source]

The following is a list of organisations and resources that will give the physiotherapist additional information and ideas for design, plan and implementation of behavioural change interventions for increased active living:

- Sport England have chosen 12 grassroots pilot projects to help build healthier more active communities across England. Over a period of four years £100m of national lottery funding will be invested in these pilot projects to create innovative solutions to make physical activity more accessible to people in these communities. The aim is to address inequalities and break down barriers that stop people getting active and encourage wider, collaborative partnerships which look at how all parts of a community can better work together and help the inactive. These partnerships will encompass organisations such as voluntary groups, social enterprises, faith organisations and parenting groups. The improvements will include transport links, street lighting, increased quality of parks and open spaces and guidance on how sport and activity is promoted by health professionals.

Key elements of Sport England’s work with young people are focused on easing transitions so that short-term lapses in participation do not become longer-term loss of habit. “Back to...” programmes have been successful increasing interest in particular sports such as netball and hockey. The focus is not just on better sign-posting through transitions but rather on changing behaviour with better opportunities that respond to the motivations of individuals as opposed to just lowering the practical barriers. If inactive youths begin to associate ‘sport’ with things they really want to do, such as meeting their friends, relaxing and de-stressing from everyday life, they are much more likely to participate.

Sport England are also using their funding to encourage sport deliverers to think differently, to make sport more accessible and participation less formal. An example of this is the investment of £500k in an innovative programme designed to get new people into sport using the National Trust brand and the idyllic settings of their properties.

One of the key features of the strategy is making sure children as young as 5 are able to enjoy physical activity and making sure experiences are enjoyable and fun. Sport England have invested a £40 million ‘Families Fund’ in projects that offer opportunities for families with children to do sport and physical activity together. Investments will also be made into free teacher training programmes, improving physical education experiences, support for satellite clubs and recognising the importance of transitions between primary and post-primary schools.

- Change4Life - Public Health England and the NHS’s ‘Change4Life’ campaign develops and implements programmes and initiatives designed to increase physical activity in youths. Change4Life uses high profile campaigns and partnerships with local authorities, schools and the commercial sector to encourage youths to achieve their guideline of 60 active minutes. There are also now Change4Life Sports Clubs in over 6,500 primary schools and all 3000 Secondary Schools. Change4Life also have a number of resources and tips available on their website for leading a more active life.

- The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Centre (NICE) consistently promote the benefits of healthy lifestyles across the curriculum at primary, secondary and higher education levels, and the benefits of group activities along with promoting campaigns for cycling and walking to school.

- Centres for Disease Control and Prevention have developed an easy-to-read Centres for Disease Control and Prevention leaflet that can be given to parents to encourage and develop ideas on how to get their child to lead a more active lifestyle outside of school.

- Parkrun is a locally-led and voluntarily-run weekly free 5km timed runs in parks throughout the country. They are open to people to all ages and standards.

- Sport Scotland – Active Schools aims to provide more and higher quality opportunities to take part in sport and physical activity before school, during lunchtime and after school, and to develop effective pathways between schools and sports clubs in the local community.

- Alliance for a Healthier Generation is a US organisation which has developed a ‘Healthy Out-of-School Time’ initiative to give out-of-school time providers a science-based framework designed to help create environments where youth are encouraged to eat healthier and move more. An assessment tool is provided to track what you are already doing to support health and wellness and highlight opportunities and strategies for growth and improvement.

Mobile Apps[edit | edit source]

Given that many young people constantly use mobile phones on a daily basis, mobile phones can be a viable tool to promote an active lifestyle and deliver positive health interventions [52]. Mobile Apps can be selected according to individual needs of the participant and can be a fun, interactive, cost-effective and social platform to encourage a more active lifestyle [53]. Apps can enable users to set targets, enhance self‐monitoring, and increase awareness [54].

There are vast amounts of different mobile apps available that focus on healthy living and physical activity, however the below list is a small selection of free apps that may be helpful to promote an active lifestyle:

- Active 10 Walker: An NHS approved app for people looking for easy ways to add activity to their day and improve their health by getting into the habit of walking briskly for 10 minutes every day. IOS download Android download

- Couch to 5k: An NHS approved app designed to get people off the couch and running 5km in 9 weeks. IOS download Android download

- Dungeon Runner Fitness Quest: The user progresses through the game by fighting enemies with punches, opening secret passages with squats and avoiding traps with ski-jumps. This app incorporates motion-tracked exercises through the gram to encourage physical activity. IOS download

- Rise & Recharge: Developed to help reduce sitting time and encourage regular movement. IOS download Android download

- Geocaching ®: Geocaching is a real-world, outdoor treasure hunting game using GPS-enabled devices. Participants navigate to a specific set of GPS coordinates and then attempt to find a container hidden at that location. IOS download Android download

- Zombies, Run! 5 K Training: A training program, with a series of missions, whereby the user runs and listens to various audio narrations to collect virtual supplies and gets fit to escape the zombies. IOS download Android download

- Charity Miles: Earn money for charities every time you run, walk, or bicycle. Corporate sponsors agree to donate a few pennies for every mile you complete. IOS download Android download

- Fitnett: An abundance of five to seven-minute targeted workouts. The app also incorporates the phone’s camera to measure how closely the participant follows the moves on the screen. IOS download

- Pokémon Go: Encourages people to get off the couch and become more active by exploring the outside world. Participants complete a variety of objectives with the opportunity to earn rewards and discover various Pokémon. IOS download Android download

- Ingress: Transforms the real world into a landscape for a global game of mystery, intrigue, and competition. The app encourages users to get off the couch and become active by trying to complete objectives and take over hack points. IOS download Android download

- Sworkit: A number of built-in exercise regimens, including yoga, that simply gets people moving all the way up to 60-minute workouts. The workouts can be personalised with over 160 exercises. IOS download Android download

- Strava: Tracks running and riding with GPS, offers options to join challenges, share photos from activities and follow friends activities. IOS download Android download

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

The increase of habitual sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity within the young population is a major contributor to the development of chronic health conditions and increased mortality rates in later life. Promoting an active lifestyle in the young population could reduce these risks and assist in carrying healthy behaviours into adulthood. Physiotherapists are ideally placed to play a crucial proactive role in promoting and facilitating an active lifestyle in the young population.

As the roles and responsibilities of physiotherapists are emerging there has been a shift away from the traditional clinical setting to a more community-based approach. In this setting physiotherapists can act as facilitators for the adoption of active living in a wider population, thus making a larger positive impact in the young population. Administering tools, such as the modified IPAQ-SF, in a community setting enable physiotherapists to identify which stage of the TTM of behaviour change young people are in. This is crucial, as physiotherapists can utilise their skills and knowledge, such as motivational interviewing and signposting, to promote and encourage an active lifestyle to young people in the early stages of the TTM. Additionally, for young people identified in the maintenance stage of the TTM, physiotherapists can utilise individualised strategies to enable young people to stay in this stage, rather than regressing. As behaviours of active living established in young years can greatly impact on maintaining positive habits across a person’s lifespan, It is of the utmost importance to enable young people to stay in the maintenance stage, thus potentially decreasing the future risks of chronic health and early mortality rates. As role models of healthy living physiotherapists will play a role in positively influencing decisions that impact on the health and well-being of communities. As the saying goes "prevention is better than cure" and physiotherapists have a role and responsibility to do more to prevent people having to present at emergency and out-patient settings due to non-communicable diseases.

"Lack of activity destroys the good condition of every human being, while movement and methodical physical exercise save it and preserve it" Plato

Further Reading[edit | edit source]

If you wish to further develop your knowledge of active living and behaviour change for young people, please utilise the links below...

- Active Living Research

- The Association of Paediatric Chartered Physiotherapists

- Consent and Physiotherapy Practice

- Behaviour Change:General Approaches (NICE 2007)

- Training professionals in motivational interviewing (The Health Foundation 2011)

- Energising Lives: A guide to promoting physical activity in primary care (NHS Scotland 2008)

- Young people: Practical strategies for promoting physical activity

- Healthy Futures: Physical activity and active living

- Allied Health Professions into Action: Using allied health professionals to transform health, care and well-being

- Promoting physical activity for children and young people (NICE 2015)

- Motivation and Confidence: What does it take to change behaviour?

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Välimäki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood. American journal of preventive medicine. 2005 Apr 1;28(3):267-73.

- ↑ Obesity and overweight reports [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2018 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- ↑ Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. Jama. 2012 Feb 1;307(5):483-90.

- ↑ Hills AP, King NA, Armstrong TP. The contribution of physical activity and sedentary behaviours to the growth and development of children and adolescents. Sports medicine. 2007 Jun 1;37(6):533-45.

- ↑ Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, Van Mechelen W, Pratt M, Lancet Physical Activity Series 2 Executive Committee. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. The Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388(10051):1311-24.

- ↑ Active SA. A report on physical activity for health from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. The Department of Health. 2011.

- ↑ World Health organization WHO. Global Health Risks-Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Cancer. 2017 Feb 3.

- ↑ Paffenbarger Jr RS, Hyde R, Wing AL, Hsieh CC. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. New England journal of medicine. 1986 Mar 6;314(10):605-13.

- ↑ Harold W. Kohl, I., Cook, H., Environment, C., Board, F. and Medicine, I. (2018). Physical Activity and Physical Education: Relationship to Growth, Development, and Health. [online] Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201497/\ [Accessed 22 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 healthy Children Org 11 Ways to Encourage Your Child to Be Physically Active Available:https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/fitness/Pages/Encouraging-Your-Child-to-be-Physically-Active.aspx (accessed 9.10.2021)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviours. American psychologist. 1992 Sep;47(9):1102.

- ↑ Telama R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a review. Obesity facts. 2009;2(3):187-95.

- ↑ Kahlert D. Maintenance of physical activity: Do we know what we are talking about?. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2015 Jan 1;2:178-80.

- ↑ Active Living [Internet]. Healthy Alberta. 2018 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20120403195030/http://www.he

- ↑ What is active living. [Internet].Active Living Research Group. 2018 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: https://www.activelivingresearch.org/active-living-topics

- ↑ What is moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity physical activity. [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2014 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: http://www. who. int/dietphysicalactivity/physical_activity_intensity/en

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, Chastin SF, Altenburg TM, Chinapaw MJ. Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)–terminology consensus project process and outcome. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017 Dec;14(1):75.

- ↑ Hoare E, Milton K, Foster C, Allender S. The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: a systematic review. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2016 Dec;13(1):108.

- ↑ Biddle, S.J. and Asare, M., 2011. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. British journal of sports medicine, p.bjsports90185.

- ↑ Penedo FJ, Dahn JR. Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2005 Mar 1;18(2):189-93.

- ↑ Physical activity statistics [Internet]. British Heart Foundation. 2015 [cited 22 March 2018]. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-activity-statistics-2015.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 European Region of the World Confederation for Physical Therapy Promoting Physical Activity in Children, the Role of Physiotherapists. [ebook] EU Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. 2018 January 11. Available at: http://www.erwcpt.eu/file/164 [Accessed 05/10/18).

- ↑ Public Health England. Making every contact count [online] 2016 January. Leeds: Crown [viewed 10 April 2018] Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/mecc-guid-booklet.pdf.

- ↑ McPhail S. Multi-morbidity, obesity and quality of life among physically inactive Australians accessing physiotherapy clinics for musculoskeletal disorders. Physiotherapy Journal. 2015 May 1; 101:986-987.

- ↑ Trudeau F, Shephard RJ. Contribution of school programmes to physical activity levels and attitudes in children and adults. Sports medicine. 2005 Feb 1;35(2):89-105.

- ↑ Wright A, Roberts R, Bowman G, Crettenden A. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation for children with physical disability: comparing and contrasting the views of children, young people, and their clinicians. Disability and rehabilitation. 2018 Jan 30:1-9.

- ↑ Brunton G, Harden A, Rees R, Kavanagh J, Oliver S, Oakley A. Children and physical activity: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators.

- ↑ Martins J, Marques A, Sarmento H, Carreiro da Costa F. Adolescents’ perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of physical activity: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health education research. 2015 Aug 31;30(5):742-55.

- ↑ Estabrooks PA, Lee RE, Gyurcsik NC. Resources for physical activity participation: does availability and accessibility differ by neighborhood socioeconomic status?. Annals of behavioral medicine. 2003 Apr 1;25(2):100-4.

- ↑ Eyre EL, Duncan MJ, Birch SL, Cox VM. Low socio-economic environmental determinants of children's physical activity in Coventry, UK: A Qualitative study in parents. Preventive medicine reports. 2014 Jan 1;1:32-42.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Haas S, Nigg CR. Construct validation of the stages of change with strenuous, moderate, and mild physical activity and sedentary behaviour among children. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2009 Sep 1;12(5):586-91.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Armitage CJ. Is there utility in the transtheoretical model? British Journal of Health Psychology. 2009 May 1;14(2):195-210.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Woods C, Mutrie N, Scott M. Physical activity intervention: a transtheoretical model-based intervention designed to help sedentary young adults become active. Health education research. 2002 Aug 1;17(4):451-60.

- ↑ Marcus BH, Forsyth LH. Motivating people to be physically active. Human Kinetics; 2009.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Romain AJ, Horwath C, Bernard P. Prediction of physical activity level using processes of change from the transtheoretical model: experiential, behavioral, or an interaction effect? American Journal of Health Promotion. 2018 Jan;32(1):16-23.

- ↑ Nigg CR, Courneya KS. Transtheoretical model: Examining adolescent exercise behaviour. Journal of adolescent health. 1998 Mar 1;22(3):214-24.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, Fiore C, Harlow LL, Redding CA, Rosenbloom D, Rossi SR. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviours. Health psychology. 1994 Jan;13(1):39.

- ↑ Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Fava J. Measuring processes of change: applications to the cessation of smoking. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1988 Aug;56(4):520.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American journal of health promotion. 1997 Sep;12(1):38-48.

- ↑ Lenio JA. Analysis of the Transtheoretical Model of behaviour change. Journal of Student research. 2006; 5:73-87

- ↑ DiClemente CC, Velasquez MM. Motivational interviewing and the stages of change. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2002;2:201-16.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Middleton KR, Anton SD, Perri MG. Long-term adherence to health behavior change. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2013 Nov;7(6):395-404.

- ↑ Müller-Riemenschneider F, Reinhold T, Nocon M, Willich SN. Long-term effectiveness of interventions promoting physical activity: a systematic review. Preventive Medicine. 2008 Oct 1;47(4):354-68.

- ↑ Robison J, Rogers MA. Adherence to exercise programmes. Sports Medicine. 1994 Jan 1;17(1):39-52.

- ↑ Tengland PA. Behavior change or empowerment: On the ethics of health-promotion strategies. Public Health Ethics. 2012 Jul 1;5(2):140-53.

- ↑ Tengland PA. Empowerment: A conceptual discussion. Health Care Analysis. 2008 Jun 1;16(2):77-96.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 NHS Scotland. Everyone matters: 2020 workforce vision. Edinburgh:NHS Scotland; 2011. 8 p.

- ↑ Hongu N, Kataura MP, Block LM. Behavior change strategies for successful long-term weight loss: Focusing on dietary and physical activity adherence, not weight loss. Journal of Extension. 2011 Feb;49(1):1-4.

- ↑ DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2004 Mar;23(2):207.

- ↑ Lindqvist AK. Physiotherapists enabling school children's physical activity using social cognitive theory, empowerment and technology. European Journal of Physiotherapy. 2017 July 3;19(3):147-53.

- ↑ Spink KS, Carron AV. Group cohesion and adherence in exercise classes. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 1992 Mar;14(1):78-86.

- ↑ Direito A, Jiang Y, Whittaker R, Maddison R. Smartphone apps to improve fitness and increase physical activity among young people: protocol of the Apps for IMproving FITness (AIMFIT) randomized controlled trial. BMC public health. 2015 Dec;15(1):635.

- ↑ Chan A, Kow R, Cheng JK. Adolescents' Perceptions on Smartphone Applications (Apps) for Health Management. Journal of Mobile Technology in Medicine. 2017 Aug 9;6(2):47-55.

- ↑ Dute DJ, Bemelmans WJ, Breda J. Using mobile apps to promote a healthy lifestyle among adolescents and students: a review of the theoretical basis and lessons learned. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2016 Apr;4(2).