Equine Spinal Pathology

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Back-pain is a common issue in horses, potentially causing chronic pain, muscle wastage, reduced performance, and decreased ability to work.[1][2]

Obtaining a definitive diagnosis is, however, difficult because of difficulties accessing the area, variability in pain manifestations[1] and vague clinical signs.[2] There is also a lack of knowledge about the equine thoracolumbar spine (particularly its functional aspects) and the pathogenesis of back problems in horses.[2] Moreover, some horses can continue to perform well despite back pathology, but others will perform poorly in the absence of specific spinal dysfunction.[2]

Back problems in horses are often related to chronic or long-standing injuries. There may also be more than one spinal lesion affecting the horse’s performance and causing symptoms. It is, therefore, important to confirm if there are any secondary lesions in order to provide a realistic prognosis and develop an optimal management plan.[2]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Equine back disorders can be classified as primary or secondary.[2][3]

Primary Back Problems[edit | edit source]

Primary disorders relate to lesions in the spinal structures, including muscle, ligament, osseous / vertebral, and nerve injuries.[3] The following table, adapted from Hinchcliffe and colleagues, lists common primary back problems.[2]

| Soft Tissue Injury | Osseous Injury | Neurological Injury | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longissimus muscle strain | Conformational / developmental abnormality | Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis | Tack and saddle fit |

| Supraspinous ligament sprain or desmitis | Overriding dorsal spinous processes (OSP) | Equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy | Idiopathic |

| Dorsal sacroiliac ligament sprain or desmitis | Osteoarthritis | Equine herpesvirus myeloencephalitis | |

| Exertional rhabdomyolysis | Vertebral fracture | Equine notor neuron disease | |

| Non-specific soft tissue injury | Spondylosis | ||

| Discospondylitis | |||

| Spinal neoplasia |

Secondary Back Problems[edit | edit source]

Secondary back problems are associated with lesions in the axial skeleton.[3] These may include:[2][3]

- Hind limb lameness

- Front limb lameness

- Neck problems (e.g. stenotic myopathy)

- Acute sacroiliac injury

- Chronic sacroiliac disease

- Pelvic fracture

Scientifically Unproven Causes of Equine Back Problems[edit | edit source]

Some proposed causes of equine back problems are not currently supported by scientific evidence, including:[2]

- Vertebral subluxation / misalignment

- Intervertebral disc injury

- Peripheral neuropathy (i.e. “pinched nerve”)

Relationship of back pain to lameness[edit | edit source]

Lameness is not a typical feature of primary back problems, but it is often associated with secondary back pain:[2]

- One study by Jeffcott and colleagues injected lactic acid into the left longissimus dorsi muscles to induce back pain in horses and determine its effect on lameness, but they found no obvious gait disturbance[4]

- Other studies show varying levels of association between naturally-occurring back pain and lameness in horses[2]

Sacroiliac Joint Pain[edit | edit source]

Possible causes of sacroiliac joint (SIJ) pain may include:[2]

- SIJ / lumbosacral osteoarthritis

- Sacroiliac desmitis / sprain

- Sacroiliac luxation

- Pelvic stress fractures

- Ilial wing or sacral fractures

Other conditions that should be considered in a differential diagnosis include:[2]

- Thrombosis of the caudal aorta or iliac arteries

- Exertional rhabdomyolysis

- Trochanteric bursitis

- Impinged dorsal spinous processes

Predisposing factors[edit | edit source]

Conformation:[2]

- Horses with short, inflexible spines are more likely to have vertebral (osseous) problems

- Horses with long, flexible spines are more likely to have muscular / ligamentous strains

Management problems:[2]

Temperament:[2]

- Excitable horses appear to be more prone to back pain - this may be due to:

- Low pain threshold

- Hypersensitivity - inclination to buck or spook

- Hyperexcitability leading to more tension / spasm in their back muscles

Mares in season (i.e. heat / oestrus):[2]

- May have associated back pain and poor performance

Schooling and work regime:[2]

- It is necessary to ensure horses are properly fit for their work / sport in order to avoid muscle strains / fatigue

- Bored horses may be reluctant to work and this can be misinterpreted as a functional issue related to back pain

Dental problems and bitting:[2]

- Mouth pain can cause tension in spinal musculature

- Horses may have: raised head carriage, back muscle tension or their hind limb impulsion may be affected

Vertebral Anomalies and Deformities[edit | edit source]

Congenital abnormalities affecting the curvature of the spine are:[2]

- Scoliosis

- Lordosis

- Kyphosis

Scoliosis and lordosis are often seen in conjunction with other deformities in newborn foals:[2]

- Severe cases may require euthanasia

- Mild cases often resolve spontaneously with growth

Kyphosis is most commonly seen during active growth after a horse has weaned and it may be associated with rapid hind limb growth rather than a specific primary spinal deformity.[2]

Congenital lordosis (sway back) is associated with hypoplasia (underdevelopment) of the cranial and caudal intervertebral articular processes between T5 and T10. Acquired lordosis may occur in brood mares after a number of pregnancies, but this does not typically cause clinical symptoms.[2]

Any deformity of the spine can cause weakness in a horse’s thoracolumbar spine and, thus, increase the risk of injury and poor performance.[2]

Soft Tissue Injuries[edit | edit source]

Muscle Strain[edit | edit source]

Epaxial (i.e. dorsal side) muscle strains are the most common cause of back injury in horses.[2] The clinical signs of a muscle strain are:[2]

- Acute onset of a reduction in performance

- Change in temperament

- Local swelling and heat may occur (especially in the lumbar region)

- Rigid back, restriction in hind limb movement or wide rear limb stance / movement

- Disunited canter

- Obvious pain on palpation

Ligamentous Damage[edit | edit source]

The supraspinous ligament is commonly injured. These injures occur most commonly in the cranial lumbar region. The clinical signs are similar to muscle injuries as described above, but symptoms tend to last longer.[2]

- The ligament is often visibly thickened and tender on palpation

- These injuries tend to recur, so prognosis is guarded

Osseous Pathology[edit | edit source]

Spinal and SIJ disorders are common causes of ongoing poor performance in horses.[2]

Articular pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

There are typically three phases of progression of articular degeneration:

- Dysfunction[2]

- Characterised by restricted joint motion, which can lead to bone demineralisation, capsular adhesions and loss of ligamentous strength

- Localised pain and inflammation, which can lead to joint capsule pathology and periarticular fibrosis

- Paraspinal muscle hypertonicity, which can contribute to the formation of adhesions.[2]

- Instability[2]

- Characterised by cartilage, capsule and ligament deformation

- Subchondral bone changes occur

- Proprioception and the central motor control of joint movement and posture are affected

- Degeneration[2]

- Osteophytes

- Ligament ossification

- Spinal ankylosis

Articular Process Degenerative Joint Disease[edit | edit source]

Degnerative joint disease of the articular processes is a common spinal disorder associated with back pain. The thoracolumbar junction and cranial lumbar spine are common sites for articular surface lipping and peri-articular erosions. The caudal lumbar vertebrae are a common site for intra-articular erosions and ankylosis.[2]

Impinged or Over-Riding Dorsal Spinous Processes[edit | edit source]

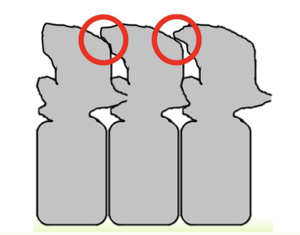

Impinged or over-riding dorsal spinous processes (OSP) (also known as ‘kissing spine’) occurs when the spinous processes of the vertebrae are too close together and overlap / touch. A distance between spinous processes of less than 4mm is considered significant.[6]See figure 1.

OSP is a common cause of osseous back pain in horses, often occurring between T13 and T18, with T15 the most commonly affected.[2] This is the area where the dorsal spinal process angles change orientation and it is directly under the saddle and rider's seat.[7] OSP can occur in the lumbar spine, but not as frequently.[7]

Almost all movement in the equine thoracic spine occurs between T7 and T18 as is summarised in the following table.

| Thoracic Movement | Location Where Most Movement Occurs |

|---|---|

| Flexion | T17-L2 |

| Extension | T17-L2 |

| Lateral Flexion | T9-T15 |

| Rotation | T7-T18 |

OSP is a radiographic diagnosis,[8] but radiographic signs are not necessarily related to clinical signs, and it is frequently an incidental finding.[5] It is more common in equine athletes who experience greater stress on their spines, but it has also been observed in wild and extinct equine species and occurs in around 30 percent of the healthy horse population.[5][9]

The underlying cause of OSP is unknown,[10] but the following factors may play a role:[5]

- Conformation

- Genetics

- Being ridden too early

- Being ridden in a poor frame, which causes excessive spinal extension

- Injuries to the spine

- Repetitive spinal extension activities such as landing after a jump

Pain associated with OSP is likely due to friction between the spinous processes, which irritates the surrounding tissue. This can result in:[5]

- Inflammation

- Swelling

- Degeneration of the supraspinous ligament

- Formation of bone spurs

The symptoms of OSP are variable in terms of severity - they can range from a slight deterioration in performance to severe lameness. Specific symptoms may include:[5]

- Muscle wastage

- Aggression when being saddled

- Resistance to lateral bend when ridden

- Lameness

- Refusal to go forward in the canter

- Refusal to jump

While OSP is fairly easy to diagnose on x-ray, there are many associated problems that cannot be seen on imaging which also contribute to a horse’s pain. The presence and severity of these problems can affect the clinical outcomes for a horse following treatment.[5]

Specific problems associated with OSP include:[5]

- Supraspinous ligament degeneration

- Ventral longitudinal ligament damage

NB While kissing spine is commonly seen on X-ray, a powerful machine is required to penetrate the thick muscles of the area, so horses usually need to go to a clinic for spinal X-rays. Ultrasound scans can detect inflammation and damage to the supraspinous ligament, and wasting of the deep muscles of the spine. Scintigraphy will show areas of active inflammation, which can be helpful in identifying specific areas of pain.[5]

Vertebral lamina stress fractures[edit | edit source]

Stress fractures tend to occur bilaterally and are more common in equine athletes who engage in strenuous or repetitive activities.[2] In one study of 36 thoroughbred racehorses, 50 percent had at least one vertebral stress fracture.[11] It is difficult, however, to diagnose stress fractures antemortem, as the area is not easily visualised on radiographs. Scintigraphy may demonstrate active stress fracture sites.[5]

Spondylosis[edit | edit source]

Spondylosis is a degenerative disease of the vertebral joints.[2] It usually occurs at multiple sites and large osteophytes form which bridge the gap between vertebral bodies. While the cause is not known, abnormal loading leads to microtrauma and ossification of the annulus fibrosis and ventral longitudinal ligament occurs. The vertebral osteophytes and ankylosing vertebral bodies are at increased risk of fracture.[2]

Vertebral Fractures[edit | edit source]

- Spinous process fractures of the whithers (T2-T9)[2]

- Usually occur when a horse falls over backward

- Not typically associated with spinal cord compromise and conservative treatment is usually recommended

- Vertebral end-plate fractures[2]

- More common in foals

- Caused by falls / significant trauma

- Vertebral body compression fractures[2]

- Usually occur in the thoracolumbar region

- Usually occur secondary to trauma, electric shock or a lightning strike

- Typically there is minimal displacement

- Sacral fractures[2]

- A common cause of cauda equina injury

- They typically occur when a horse forcefully backs into a solid object or falls over backwards

Sacro-Pelvic Pathology[edit | edit source]

Sacroiliac Desmitis[edit | edit source]

Sacroiliac desmitis can be seen on ultrasound in the dorsal portion of the dorsal sacroiliac ligament. Complete sacroiliac disruption is not common, and is usually due to substantial trauma.[2]

Differences in Tuber Sacrale Height[edit | edit source]

This condition can occur spontaneously or insidiously. It may be caused by chronic, asymmetric muscular or ligamentous forces acting on the pelvis. It is not necessarily associated with sacroiliac ligament injury. Clinicians should not assume, therefore, that it is a sign of sacroiliac joint luxation.[2] This condition is not necessarily associated with pain or loss of performance. Diagnosis of sacroiliac luxation is only supported by:[2]

- History of major trauma

- Crepitus

- Independent tuber sacrale movement

Pelvic Fractures[edit | edit source]

The most common pelvic fracture is a complete ilial wing fracture. A depressed tuber sacrale on the affected side can usually be palpated. There is a high prevalence of occult pelvic stress fractures in thoroughbred race horses. They tend to occur on the caudal border of the ilium next to the SIJ and may cause SIJ inflammation and damage.[2]

Management of Equine Spinal Pathology[edit | edit source]

Severe pathology or pain requires:[5]

- Stable rest

- Restricted or controlled exercise

- Graduated exercise programme

- Replace / re-flock saddle / therapeutic saddle pads

- Change work routine / training approach

- Rider’s technique and ability are also important factors, but they:

- Difficult to modify

- May require discussion with trainer / instructor

Medical/ surgical treatment:[2]

- NSAIDs

- Corticosteroids

- Muscle relaxants

- Sclerosing agents

- Used in severe cases of OSP

- Hormonal therapy

- For mares who exhibit periods of back pain during oestrous

- Surgical excisions are not commonly performed, but may be used for:

- Comminuted or compound fractures of the whithers

- Impinging dorsal spinous processes

Other treatments:[2]

- Physiotherapy

- Massage therapy

- Chiropractic

- Acupuncture

- Homeopathy

- Nutraceuticals

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Riccio B, Fraschetto C, Villanueva J, Cantatore F, Bertuglia A. Two multicenter surveys on equine back-pain 10 years a part. Front Vet Sci. 2018;5:195.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 2.33 2.34 2.35 2.36 2.37 2.38 2.39 2.40 2.41 2.42 2.43 2.44 2.45 2.46 Hinchcliff KW, Kaneps A, Geor R. Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery. 1st Edition. Saunders Ltd. 2004.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Mayaki AM, Intan-Shameha AR, Noraniza MA, Mazlina M, Adamu L, Abdullah R. Clinical investigation of back disorders in horses: A retrospective study (2002-2017). Vet World. 2019;12(3):377-81.

- ↑ Jeffcott LB, Dalin G, Drevemo S, Fredricson I, Björne K, Bergquist A. Effect of induced back pain on gait and performance of trotting horses. Equine Vet J. 1982;14(2):129-33.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Van der Walt A. Equine spine pathology presentation. Physioplus. 2021.

- ↑ Sinding MF, Berg LC. Distances between thoracic spinous processes in Warmblood foals: a radiographic study. Equine Vet J. 2010;42(6):500-3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Young A. What are kissing spines? [Internet]. UCDavis Center for Equine Health. 2019 [cited 28 May 2021]. Available from: https://ceh.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/health-topics/kissing-spines

- ↑ Turner TA. Overriding spinous processes (“kissing spines”) in horses: Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome in 212 Cases. AAEP Proceedings. 2011;57:424-30.

- ↑ De Cocq P, Van Weeren PR, Back W. Effects of girth, saddle and weight on movements of the horse. Equine Veterinary Journal. 2004;36(8):758-63.

- ↑ Gray L. Kissing spines [Internet]. SmartPak. 2018 [cited 28 May 2021]. Available from: https://www.smartpakequine.com/content/kissing-spine-horse

- ↑ Haussler KK, Stover SM. Stress fractures of the vertebral lamina and pelvis in Thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet J. 1998;30(5):374-81.