Mindfulness for our Patients

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Merinda Rodseth, Kim Jackson, Jess Bell, Tarina van der Stockt, Ewa Jaraczewska and Aminat Abolade

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Over the last 40 years there has been a great shift in mindset from the traditional “biomedical” tissue-based model of health care to a biopsychosocial model (Bevers 2016, Jull 2017, Bolton 2020). The biopsychosocial model assesses the “whole person”, taking into account the dynamic interactions between the bio, psycho and social factors of the pain-experience process (Bevers 2016, Parker 2020). “Understanding that every thought, every feeling and every interaction with the environment is linked to a chemical reaction in the neuroimmune system, with possible structural and functional consequences, increases the clinician’s insight and truly embeds biopsychosocial thinking into practice” (Parker 2020).

Pain is the most common reason for people seeking healthcare and when unresolved results in chronic pain (pain lasting longer than 3 months) which has become a major public health problem globally (Smith 2020, Parker 2020, Hilton 2017). Chronic pain also poses a significant therapeutic challenge and has subsequently lead to a change in focus from studying tissue damage to studying pain itself (Parker 2020, Smith 2020). Focusing our attention on the person rather than on the tissues has caused a shift in treatment from a single-minded focus on elimating pain to the a much bigger goal of improving quality of life and enabling patients to re-engage in life roles that are meaningful to them (Parker 2020). This is reiterated in the concept of mindfulness where the goal is not to eliminate pain or stress, but rather to teach patients to be self-aware and respond to stress and pain in a more constructive and healthy way (Shrey talk part2, Smith 2020). Empowering patients to be in control of their own pain experience is fundamental to this patient-centered care and enables patients to self-manage and recover their life roles (Parker 2020).

Recognising Potential Patients[edit | edit source]

Despite its proposed benefits, mindfulness practice is not considered a panacea for all conditions, people and circumstances (Shapiro 2017). Even though mindfulness practice would probably be beneficial to most individuals, its impact on a smaller subset of patients could be much more enhanced. Consideration of the established effects and benefits of mindfulness could act as a guide to physiotherapists as to which patients would potentially most benefit from mindfulness training, and are proposed to include the following subgroups (Shrey talk):

- Patients with persistent and chronic pain (McClintock 2019, Zeidan 2019, Smith 2020)

- Chronically stressed, anxious, worried and tense patients (Creswell 2017)

- Rumination on the past or the future (this becomes evident in key phrases and words used by patients) (Creswell 2017, Shapiro 2017)

- Motivated patients (Shapiro 2017)

- Good therapeutic relationship (Shapiro 2017)

Integrating Mindfulness in Clinical Practice[edit | edit source]

Germer et al (2005) conceptualised three pathways in which to integrate mindfulness into therapeutic work:(Germer, Siegel and Fulton 2005)

- Personal practice of mindfulness in order to cultivate a mindful presence in therapeutic work - mindful therapist

- Integrating the wisdom and insights from the psychological mindfulness literature into one’s own therapeutic practice - mindfulness-informed therapy

- Explicitly teaching mindfulness skills and practices to patients to enhance their own mindfulness - mindfulness-based therapy

Considering the concept of being a “mindful therapist”, it is important to be aware that “relationship” has proven to be the strongest predictor of the outcomes of therapy. “Relationships characterised by empathy, unconditional positive regard, and congruence between therapist and client have proven most beneficial” (Shapiro 2017). Thich Nhat Hanh stated: “A therapist has to practice being fully present and has to cultivate the energy of compassion in order to be helpful” (Shapiro 2017). Therefore, introducing patients to mindfulness practice should really start with a mindful attitude of the therapist (Shapiro 2017).

Mindfulness practice can also be utilised using the framework that supports the concepts cultivated by it, i.e. mindfulness-informed practice. Shapiro & Carlson (2017) highlighted a few potential points for exploration based on insights informed by mindfulness that may be useful to explore with patients during therapy:

- Impermanence - the fact that everything changes and life is not static, permanent and unchanging

- No “self” - the concept that “self” is also ever-changing and in continuous flux

- Accepting what is - much of our suffering follows our resistance of what is actually happening, wanting things to be different from what they are. “What we resist, persists”. When we resist our experience, we increase our suffering.

- Conscious responding versus automatic reactivity - stop and attend to stimuli/problems/emotions instead of automatically reacting

- Curiosity and investigation of one’s own experience - paying attention specifically to the body, feelings, the mind and the underlying principles of experience. Be curious about internal experiences and explore them.

- Paradox can be a means of liberation, an instrument to move beyond the usual way of seeing things to a position of greater flexibility and perspective (e.g. “to care and not to care”)

- Interdependence - all things are connected and mutually interdependent, we are not seperate or isolated

- Essential nature/inherent goodness

Mindfulness practice, with its origins in Buddhist philosophy, is often not widely accepted in the Western world. Some patients might be resistant to its use even though it could be separated from its religious roots, which may necessitate a measure of convincing them to engage in it. Hence, approaching it according to the following steps might gain better acceptance of it:

- Mindfulness practice should be introduced in a gentle, non-judgemental and open way.

- Exploring mindfulness can start with bare awareness to simple breathing (Shapiro 2017). Incorporate easy breathing techniques into the patient’s daily routine/exercise program while asking them to pay attention to their breath - feeling the breathing in and breathing out, the rise and fall of the abdomen, the “touch of air at the nostrils” (Shapiro 2017).

- The simple breathing exercises can be progressed to more specific breathing techniques such as the “3-minute breathing space” (Shapiro 2017), “4-7-8 breathing” and “box breathing” (Shrey talk)

- Provide patients with handouts and additional resources to increase their knowledge.

- Engage patients in guided meditations performed either by a therapist or through the use of mindfulness applications available online or on smartphones (Apps).

- Help patients find structured or community mindfulness programs (i.e. 6-14 week programs).

- Encourage patients to engage in the long-term practice of mindfulness for maximal benefit (Zeidan 2019).

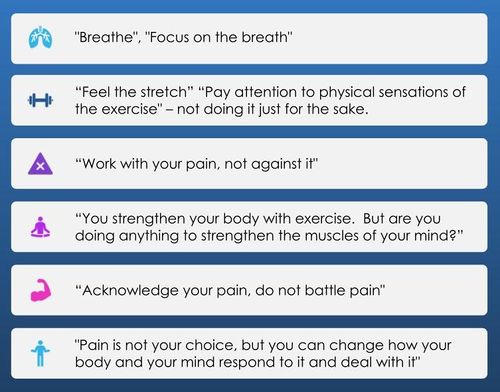

Phrases that may be useful to engage patients in mindfulness practice during therapy include:(Shrey talk)

Mindfulness-Based Applications[edit | edit source]

The popularity of mindfulness combined with the ubiquity of smartphones has led to an exponential increase in Mindfulness-Based mobile Applications (MBAs) available. MBAs have been shown to effectively reduce stress and improve wellbeing and can target wider audiences than typical mindfulness meditation training, making mindfulness more accessible to the general public (Nunes 2020, Dauden 2018, Flett 2018). Apps increases flexibility in terms of time and place and offer reminder functions and supporting material (pictures, videos), facilitating the integration of mindfulness techniques into daily life (Schultchen 2020). MBAs mostly focus on guided meditations and often start with breathing exercises, asking the users to focus their attention on their body (Dauden 2018). There is a wide variety of MBAs available with Calm, Headspace, InsightTimer, Smiling Mind and Stop Breathe Think only being a few examples (Dauden 2018, Flett 2018, Nunes 2020). Despite the benefits seen with MBAs, it is important to note that MBAs are not necessarily beneficial for everyone and could in fact be harmful to some patients, specifically those with severe depression, PTSD, suicidal ideation and a history of trauma (Shrey talk). This leads to the concept of trauma-sensitive mindfulness, a modified trauma-informed approach to mindfulness that is much better positioned to safely facilitate mindfulness in trauma survivors where traditional mindfulness practice (including meditation apps) could potentially be harmful (Shrey talk, Treleaven 2018).

Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness[edit | edit source]

The concept that mindfulness can be a cure-all for all conditions and problems, including trauma, has resulted in some unintended consequences (Treleaven 2018). Even though many people who regularly practice mindfulness experience great benefits, not everyone has that experience - especially not those who have experienced trauma (“an extreme form of stress that can overwhelm our ability to cope”) (Treleaven 2018). Trauma and mindfulness, although seemingly allies, exhibits a complex relationship (Treleaven 2018). For many people who have experienced trauma, mindfulness can elicit symptoms of traumatic stress. This can take the form of flashbacks, volatile emotional reactions, agonizing physical sensations and dissociation - a disconnect between one’s thoughts, emotions and physical sensations (Treleaven 2018) Although mindfulness might seem an innocuous, beneficial practice for trauma survivors, it often opens emotional wounds that need more than mindful awareness for healing. “When we ask someone with trauma to pay close, sustained attention to their internal experience, we invite them into contact with traumatic stimuli - thoughts, images, memories, and physical sensations that may related to a traumatic experience….this can aggravate and intensify symptoms of traumatic stress, in some cases even lead to retraumatization - a relapse into an intensely traumatized state.” (Treleaven 2018) Focusing attention on injuries that are often internal and unseen, can cause distress, anxiety and humiliation in trauma survivors, placing them in an “unsafe” environment (Treleaven 2018). Despite this, mindfulness could also be an invaluable resource for trauma survivors - strengthening body awareness, boosting attention and improving emotion regulation, skills essential for trauma recovery (Treleaven 2018).

This dilemma raised the question as to how the potential dangers of mindfulness to trauma survivors can be minimised while simultaneously harnessing its potential benefits which gave birth to the concept of Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness (Treleaven 2018). Basic mindfulness practice is safer and more effective when paired with an understanding of trauma (Treleaven 2018). Trauma is not limited to assault survivors or combat veterans, and is surprising less about the content of an event than it is about its impact. Pat Ogden, veteran trauma specialist, stated, “any experience that is stressful enough to leave us feeling helpless, frightened, overwhelmed, or profoundly unsafe is considered a trauma” (Treleaven 2018). This can vary from witnessing or experiencing violence, losing a love one to being targeted by oppression - people experience trauma in various ways.

Treleaven & Britton (2018) defined Trauma-Senstive practice as:

“A program, organizaiton, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and seeks to actively resists re-traumatization.”

They proposed that the primary task of therapists lie in the four R’s evident in the definition: realizing the pervasive impact of trauma, recognizing symptoms, and responding to them skilfully - all with the aim of preventing re-traumatization.(Treleaven 2018)

The 5 core principles of trauma-sensitive mindfulness practice includes: (Treleaven 2018):

- Stay within the window of tolerance - the zone between hyperarousal and hypoarousal which can also be described as the internal zone/range of their experience where they can safely observe and tolerate, without exceeding what they can handle.(Treleaven 2018, Siegel 2012). It is important to motivate trauma survivors to begin tracking their window of tolerance so that they can self-regulate, knowing what they can stay present for and what they can’t tolerate.

- Shift attention to support stability - survivors must learn that they can shift their attention away from traumatic stimuli in order to support their window of tolerance (e.g. opening eyes and focussing on the environment). Establish stable anchors of attention by focusing on something other than breath, like the sensation of their feet on the floor/buttocks on the chair or the sounds around them.

- Keep the body in mind - working with dissociation. Survivors need to eventually come back into connection with their bodies, befriending their inner world through an awareness of inner body sensations. Providing choices/options such as keeping their eyes open/closed, adopting a posture that works for them and opting out of or stopping any practice, helps to create a safe environment for survivors, giving them autonomy of the situation. Be cautious of using body scan as a mindfulness technique with trauma survivors.

- Practice in relationship - use the benefits of interpersonal relationships to buoy the safety, stability and window of tolerance of trauma survivors. Trauma cannot be healed in solitude - recovery requires relationship. Screening patients for a history of trauma provides the opportunity to identify trauma survivors who might not do well with mindfulness practice and might benefit more from consulting a trauma professional first.

- Understand social context - working effectively across difference. It is important to be aware that we all have a unique history and are being shaped by the systems around us. Social context includes social identity (age, gender, race, ethnicity, class background, sexual identity, dis/ability, religion), locale (city, town, suburb), peers, community and country of residence. Trauma can affect anyone but people in marginilised social groups are more vulnerable to experience traumatic events.

Following the principles defined by Treleaven & Britton (2018) there are some trauma-sensitive modification strategies that could be useful in clinical practice when engaging patients in mindfulness practice. These include:

- Screening patients for PTSD, severe depression, trauma and suicidal ideations

- Providing options to patients during mindfulness practice (keep eyes closed/open; different postures)

- Establishing a safe environment

- Giving patients permission to step out of/stop practice at any time

- Providing patients an alternate anchor to breath, such as sounds or physical sensations

Advanced training is required to treat survivors of severe trauma and trauma practitioners are better positioned to provide the necessary intervention (Shrey talk, Treleaven 2018). Recommending the use of mindfulness apps are therefore not encouraged for patients with a history of trauma and especially not for those with PTSD, severe depression and suicidal ideation as it may result in re-traumatization (Shrey talk).

Key Considerations concerning Mindfulness[edit | edit source]

- Mindfulness is not intended to be blissful, rather, like exercise, it can be uncomfortable at times.

- Mindfulness is not the panacea/universal solution to reduce stress and improve well-being. There are many other tools and options available.

- Mindfulness is intended to be open-minded and invitation, not forcing anyone but allowing participants to explore, experiment and build a practice that best works for them.

“What we resist, persists” (Shapiro 2017)

Resources[edit | edit source]

Books:

- Gardner-Nix J, Costin-Hall L. The mindfulness solution to pain: Step-by-step techniques for chronic pain management. New Harbinger Publications; 2009. https://1lib.us/book/2475063/e12fdf

- Day MA. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for chronic pain: a clinical manual and guide. John Wiley & Sons; 2017 May 8. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=VukcDgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=Mindfulness-Based+Cognitive+Therapy+for+Chronic+Pain:+A+Clinical+Manual+and+Guide,+First+Edition.+By+Melissa+Day,+(2017).%E2%80%8B&ots=XfAhCfvGAW&sig=HAO1JdvngX-Ps1n1USp2aTMESUE#v=onepage&q=Mindfulness-Based%20Cognitive%20Therapy%20for%20Chronic%20Pain%3A%20A%20Clinical%20Manual%20and%20Guide%2C%20First%20Edition.%20By%20Melissa%20Day%2C%20(2017).%E2%80%8B&f=false

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are: Living your life as if it really matters. Integrative learning and action: a call to wholeness. 2006:157-72. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=B8MDvZbuNLQC&oi=fnd&pg=PA157&dq=Kabat-Zinn+wherever+you+go+there+you+are&ots=3MRvmd98rZ&sig=pPQu1Smvk5ZhRxD6A8p4oChKCho#v=onepage&q=Kabat-Zinn%20wherever%20you%20go%20there%20you%20are&f=false

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living, revised edition: how to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. New York: Bantam Books; 2013.Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=TVsrK0sjGiUC&oi=fnd&pg=PR17&dq=Kabat-Zinn+Full+catastrophe+living&ots=eGl872jn10&sig=Eu5x7MyA9VHxwBipmVKAjIokP6k#v=onepage&q=Kabat-Zinn%20Full%20catastrophe%20living&f=false

- Hanh TN. The Miracle of Mindfulness, Gift Edition: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation. Beacon Press; 2016. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2NkiDQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=The+Miracle+of+Mindfulness+%E2%80%93+Thich+Nhat+Hanh&ots=DyLXLLdwLH&sig=TqpnkBCK8MAWPxzxnxs5aMWexTo#v=onepage&q=The%20Miracle%20of%20Mindfulness%20%E2%80%93%20Thich%20Nhat%20Hanh&f=false

- Puddicombe A. The Headspace Guide to Meditation and Mindfulness: How Mindfulness Can. 2016. Available from: https://www.amazon.com/Get-Some-Headspace-Mindfulness-Minutes-ebook/dp/B006ZL1KAW

Videos:

- DocMikeEvans. The Single Most Important Thing you can do for your Stress. Published 9 June 2012. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I6402QJp52M [last accessed 9 April 2021].

- Andy Puddicombe (Founder of HeadSpace). All it takes is 10 mindful minutes. Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/andy_puddicombe_all_it_takes_is_10_mindful_minutes?language=en [last accessed 9 April 2021]

- Kelly McGonigal. What Science can Teach Us about Practice: The Neuroscience of Mindfulness. Published 2 Aug 2011. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jMsatDwx07o [last accessed 9 April 2021]