Myofascial Pelvic Pain

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Joseph Ayotunde Aderonmu, Khloud Shreif, David Olukayode, Kim Jackson and Leana Louw

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Myofascial Pelvic Pain (MPP) also called Myofascial Pelvic Pain Syndrome (MPPS) is a condition which affects the musculoskeletal system.[1] It is usually an unrecognized and untreated component of chronic pelvic pain (CPP) associated with high percentage of misdiagnosis, and high failure rate of medical interventions. Due to the above, it results in frustrated specialists and patients.[2]

Myofascial pelvic pain refers to pain found in the pelvic floor musculature and connecting fascia. It is characterized by adverse symptoms of tender points, myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) in skeletal muscles.[3][4] It could exist alone with no concomitant medical pathology, exist as either a precursor or sequela to urological, gynecological, and colorectal medical conditions or other musculo-skeletal-neural issues. The hallmark diagnostic indicator of MFPP is myofascial trigger points in the pelvic floor musculature that refer pain to adjacent sites.[5][1]

Studies in the CPP literature have demonstrated existence of MTrPs or hypertonic pelvic floor muscles in medical conditions of different origins.[3][6][7] Yet, MPP is often overlooked by first-line health care providers as either a primary or contributing source of pain for conditions such as urgency/frequency, urge incontinence, constipation, dyspareunia, endometriosis, vulvodynia, coccygodynia, pudendal neuralgia, post-surgical or birthing pelvic pain, interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS). [8][3][9][6][7][10][11][12]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Pelvic pain affects 3.8–24% of women ages 15–75 years old. Annually, pelvic pain is the primary indication for 10% of outpatient gynecology visits, 40% of diagnostic laparoscopies, 12–17% of hysterectomies.[13] A female chronic pelvic pain clinic reported that 14% to 23% of women with chronic pelvic pain have myofascial pelvic pain. [14] This can get as high as 78% among women with interstitial cystitis.[3][5]

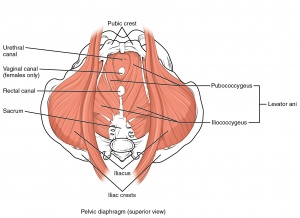

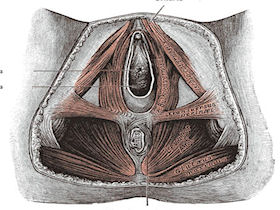

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The pelvic floor or perineum is that part of the trunk that is located below the pelvic diaphragm. The pelvic floor is bounded by [15][16]:

Anal triangle (posterior part):

Contains the anal canal, the ischiorectal fossae on each side, and the external anal sphincter;

Urogenital triangle (anterior part):

Contains the external genitalia and terminal portions of the urogenital ducts

The posterior part is closed by the pelvic diaphragm, and the anterior part of the inferior part of the pelvis is closed by the urogenital diaphragm.

Primarily, the pelvic floor musculature provide the following essential roles[17]:

- Provide support for the pelvic organs and their contents

- Withstand increases in intra-abdominal pressure

- Contribute to stabilization of the spine/pelvis

- Maintain continence at the urethral and anal sphincters

- Sexual response and reproductive function

Etiology[edit | edit source]

MPP is caused by factors that affect muscular strain, circulation and pain, which could be[18][19]:

Mechanical Factors:

Factors such as direct trauma, chronic poor posture or body mechanics, ergonomic stressors, joint hypermobility, leg length discrepancy, scoliosis, pelvic torsion can result in increased muscle strain due to low-level static exertion of the muscle during prolonged motor tasks, resulting in muscle pain and injury.[2]

Mechanical factors may also occur from prior surgeries, birthing trauma, childhood falls, injuries, accidents, illnesses, physical or sexual abuse, repetitive movement patterns, muscular strains which can cause decreased circulation, localized hypoxia, and ischemia. These conditions can ultimately result in the formation of MTrPs.[20][21]

Nutritional Factors:

Nutritional deficiencies are often common among women with MPP but often overlooked. Deficiencies of vitamins B1, B6, and B12, folic acid, vitamin C and D, iron, magnesium, and zinc have all been associated with chronic MTrPs. In people with chronic MTrPs, 16% have insufficient B12 levels, whereas 90% lack proper vitamin D.[22]

Psychological Factors:

Psychological stress may also activate underlying MTrPs. Stress, hyper-responsible personalities, depression, anxiety-depression syndrome can all contribute to the activation of MtrPs [23]. Mental and emotional stress have been shown to increase the electromyographic activity in MTrPs, whereas neighboring muscle without trigger points remains electrically unchanged.`[22]

Other factors that can result in MPP include chronic infections, metabolic factors. [18][19]

Mechanism of Myofascial Pelvic Pain[edit | edit source]

Symptoms of MPP are caused by tender points and MTrPs in pelvic floor muscles. These trigger points usually refer sensation or pain to adjacent sites. These referral patterns do not present in classic nerve or dermatomal regions, (although characteristic referral patterns for pelvic MTrPs have been well documented).[5]

Myofascial trigger points are localized, often extremely painful lumps or nodules in the muscles (“taut bands”) or associated connective tissue known as fascia.[24][5][25]

They are classified as either active, secondary or latent[26]:

Active Trigger Points:

Produce local or referred pain or sensory disturbances without stimulation.

Always sensitive.

Constantly painful spots.

Pain increases on palpation, pressing, stretching and mobilizing the muscle.

Latent Trigger Points:

Develop within reference area of original trigger point.

Will not trigger symptoms unless activated by an exacerbating physical, emotional, or other associated stressor.

They become active on activation.

Secondary TrPs:

Appear in response to the contraction of agonist and antagonist muscles that attempt to compensate for the injured muscle.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

- x

or

- numbered list

- x

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pastore EA and Katzman WB. Recognizing Myofascial Pelvic Pain in the Female Patient with Chronic Pelvic Pain. JOGNN, 41, 680-691; 2012.DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01404.x

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Itza SF, Zarza D., Serra LL., Gómez SF., Salinas J., Bautrant E. (2014). Myofascial pain syndrome in the pelvic floor: etiology, mechanisms, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.4482.7048

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Bassaly, R., Tidwell, N., Bertolino, S., Hoyte, L., Downes, K., & Hart, S. (2010). Myofascial pain and pelvic floor dysfunction in patients with interstitial cystitis.International Urogynecology Journal, 22(4), 413–418. doi:10.1007/s00192-010-1301-3

- ↑ Doggweiler-Wiygul, R. (2004). Urologic myofascial pain syndromes. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 8(6), 445–451.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Itza, F., Zarza, D., Serra, L., Gomez-Sancha, F., Salinas, J., & AllonaAlmagro, A. (2010). Myofascial pain syndrome in the pelvic floor: A common urological condition.Actas Urologicas Espanolas, 34(4), 318–326

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bendana, E. E., Belarmino, J. M., Dinh, J. H., Cook, C. L., Murray, B. P., & Feustel, P. J. (2009). Efficacy of transvaginal biofeedback and electrical stimulation in women with urinary urgency and frequency and associated pelvic floor muscle spasm. Urologic Nursing, 29(3), 171–176.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chiarioni, G., Nardo, A., Vantini, I., Romito, A., & Whitehead, W. E. (2010). Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome. Gastroenterology,138(4), 1321–1329. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.040

- ↑ Apte, G., Nelson, P., Brismee, J. M., Dedrick, G., Justiz, R., 3rd, & Sizer, P. S., Jr. (2011). Chronic female pelvic pain-part 1: Clinical pathoanatomy and examination of the pelvic region. Pain Practice: The Official Journal of World Institute of Pain, 12(2), 88–110. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011. 00465.x

- ↑ Butrick CW. Pelvic floor hypertonic disorders: Identification and management. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 2009; 36(3):707–722.

- ↑ Doggweiler-Wiygul, R. (2004). Urologic myofascial pain syndromes. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 8(6), 445–451.

- ↑ Gentilcore-Saulnier, E., McLean, L., Goldfinger, C., Pukall, C. F., & Chamberlain, S. (2010). Pelvic floor muscle assessment outcomes in women with and without provoked vestibulodynia and the impact of a physical therapy program. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(2 Pt 2), 1003–1022. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01642.x

- ↑ Neville, C. E., Fitzgerald, C. M., Mallinson, T., Badillo, S. A., Hynes, C. K. (2010). Physical examination findings by physical therapists compared with physicians of musculoskeletal factors in women with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 34(3), 73–80.

- ↑ Prather H, Spitznagle T, Dugan S. Recognizing and treating pelvic pain and pelvic floor dysfunction. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18:477–96.

- ↑ Tu, F. F., As-Sanie, S., & Steege, J. F. (2006). Prevalence of pelvic musculoskeletal disorders in a female chronic pelvic pain clinic. The Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 51(3), 185– 189

- ↑ Rouviere. Anatomía Humana, vol. 2, tronco. 2005. Editorial Masson.

- ↑ Sobotta. Atlas de Anatomía Humana - vol. 2.Putz – Pabst. 2006. Editorial Panamericana.

- ↑ Kisner C, Colby L 2012. Therapeutic exercise : foundations and techniques / Carolyn Kisner, Lynn Allen Colby. — 6th ed.p. ; cm. ISBN 978-0-8036-2574-7

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Fernandez-de-Las-Penas, C., Alonso-Blanco, C., & Miangolarra, J. C. (2006). Myofascial trigger points in subjects presenting with mechanical neck pain: A blinded, controlled study.Manual Therapy, 12(1), 29–33. doi:10.1016/j.math.2006.02.002

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Montenegro, M. L., Mateus-Vasconcelos, E. C., Candido dos Reis, F. J., Rosa e Silva, J. C., Nogueira, A. A., & Poli Neto, O. B. (2010). Thiele massage as a therapeutic option for women with chronic pelvic pain caused by tenderness of pelvic floor muscles.Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16(5), 981– 982. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01202.

- ↑ Hagg, G. M. (2003). Corporate initiatives in ergonomics.Applied Ergonomics, 34(1), 1.

- ↑ Sjogaard, G., Jorgensen, L. V., Ekner, D., & Sogaard, K. (2000). Muscle involvement during intermittent contraction patterns with different target force feedback modes.Clinical Biomechanics, 15(Suppl. 1), S25–S29. doi:10.1016/S0268-0033(00)00056-5

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Dommerholt, J., Bron, C., & Franssen, J. (2006). Myofascial trigger points: An evidence informed review.Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, 14(4), 203–221.

- ↑ Berberich HJ, Ludwig M. Psychosomatic aspects of the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urologe A. 2004 Mar; 43(3):254-60. Review.

- ↑ Harden, R. N., Bruehl, S. P., Gass, S., Niemiec, C., & Barbick, B. (2000). Signs and symptoms of the myofascial pain syndrome: A national survey of pain management providers. Clinical Journal of Pain, 16(1), 64–72.

- ↑ Simons, D. G., Travell, J. G., & Simons, L. S. (1999a).Travell and Simons’ myofascial pain and dysfunction: The trigger point manual(2nd ed., Vol.1). Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins.

- ↑ Dommerholt, J. (2005). Persistent myalgia following whiplash. [Review]. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 9(5), 326–330. doi:10.1007/s11916-005-0008-5