Growing up With Cystic Fibrosis

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Original Editor - Your name will be added here if you created the original content for this page.

Top Contributors - Laura Midori Wickham, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe, Michelle Lee, WikiSysop, Adam Vallely Farrell and Naomi O'Reilly

WELCOME[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Welcome to our information page for all people caring for individuals living with cystic fibrosis (CF). As we live in a world of technology, there are many CF websites available for public access on the Internet. Thus, our page is designed to build upon previous resources available and condense valuable information through our own critical analysis. It is our objective to provide parents and carers with a learning resource and developmental tool to ease concerns. We aim to achieve this through discussions of six important aspects of living with CF, thereby promoting self-efficacy towards assisting in the implementation of necessary changes or provide continued support.

Our mission is to advance the knowledge and participation among all readers to be well informed to assist individuals living with cystic fibrosis.

Our vision is that all readers will understand the disease and overall impact that it has for all those affected by CF. Additionally readers will be confident in assisting with the choice of appropriate treatments and become proactive about implementing any changes.

Please feel free to click on the video below to become familiar with the content our webpage has to offer and to learn how to navigate the site.

Video to come...

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

After exploring this wiki page, the reader should be able to:

- Review evidence of new and emerging treatments and or management of people with CF

- Analyze the physiotherapist’s role through the transition from paediatric to adult services for individuals with CF - good depth

- Gain insight on managing and caring for people with CF

- To accurately justify and support the use of current physiotherapy treatments and management techniques for people who suffer from cystic fibrosis.

- Better understand your condition (CF), how to manage it and how others can help you.

- Compare the research substantiating new scientific evidence and treatments available in the paediatric cystic fibrosis field

- Critically analyse the research supporting new and emerging scientific evidence and treatment available for patients with cystic fibrosis

- Cope, aid and problem solve emotional and psychological problems themselves or their children/patients may have as a result of living with cystic fibrosis.

- Identify exercises to develop physical activity plans appropriate for the individual’s level of abilities.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CYSTIC FIBROSIS[edit | edit source]

Cystic fibrosis is caused by the defective “cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductive regulator” (CFTR) gene (Zielenski 2000).

Cystic fibrosis is a monogenic recessive disease, meaning, a person usually needs the defective CFTR gene copy from each parent, in order to develop cystic fibrosis (Zielenski 2000).

- The CFTR gene affects chloride channels throughout the body (CI) which also affects sodium in the body (Na) (Gibson et al. 2003).

- It blocks the reabsorption of CL, consequently affecting the reabsorption of Na in order to maintain a balance between the two.

This defective CFTR gene can affect different organs. However, there is much variability in the severity of his disease among the different organs. This depends on the characteristics of the defective CFTR gene and the organ in question (Wilschanski & Durie 2007). For example, the pancreas and the vas deferens are more susceptible to the pathological effects of this defective CFTR gene, compared with sweat ducts and the skin; This is due to the specific physiological make up of an organ in relation to their dependence of the CFTR gene (Wilschanski & Durie 2007). In cystic fibrosis, the mainly affected organs can include the lungs, the skin, the pancreas, the male reproductive tract and the intestines (Zielenski 2000):

Lungs[edit | edit source]

This defective gene does not allow CL and therefore Na (which water follows and acts as a lubricant) to cross the epithelium in the lungs for increased moisture and lubrication. This can in turn, affect mucociliary clearance (Gibson et al. 2003).

- The lungs therefor struggle to clear mucus, due to thick secretions

- This, in turn, causes an increased chance for infection as the lungs struggle to function normally (Donaldson & Boucher 2007).

Male Reproductive Tract[edit | edit source]

The defective CFTR usually causes infertility in males with cystic fibrosis – In most cases of males with cystic fibrosis, it causes an abnormally developed vas deferens or an absence of the vas deferens (Kaplan et al 1968) (Anguiano 1992). The Vas deferens is a sperm duct which conveys sperm from the testes to the urethra in the penis. Consequently, males with cystic fibrosis have been commonly been shown to have a condition known as aspermia (Kaplan et al 1968) (Sant Agnese & David 1977) . This is a condition whereby a male does not produce semen or sperm upon ejaculation/orgasm.

Intestines[edit | edit source]

Similar to the other organs, CL and Na blockage due to malfunctioning CL channels from the defective CFTR gene can be present in the intestines. This can disrupt fluidity in these areas (Berschneider 1988) due to the aforementioned Na which attracts water.

Skin[edit | edit source]

Cl channels which allow for reabsorption back into the body are affected in sweat glands (which also affects reabsorption of Na).

- Therefore, these ions must cross over to the skin which can cause very salty sweat.

Pancreas[edit | edit source]

Blockage of CL & Na secretions can affect secretions of substances like insulin.

- This can then lead to diabetes which is very common in cystic fibrosis sufferers (Moran 2004).

Essential nutrients and enzymes can also be affected by this.

- This may lead to malnourishment, delay in puberty and therefor, restricted growth in children (Moran 2004).

Check Point: Try these self-assessment questions below[edit | edit source]

EMOTIONAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT[edit | edit source]

K.C's info to come...

Check Point: Try these self-assessment questions below[edit | edit source]

PHYSIOTHERAPY TREATMENTS[edit | edit source]

T.C's info to come...

Check Point: Try these self-assessment questions below[edit | edit source]

EXERCISE[edit | edit source]

It is important to understand that not all physical activity is considered exercise. Be aware of the difference between exercise and physical activity. We encourage you to make a conscious effort to engage in planned activities regularly to become an exerciser!

Benefits and Risks[edit | edit source]

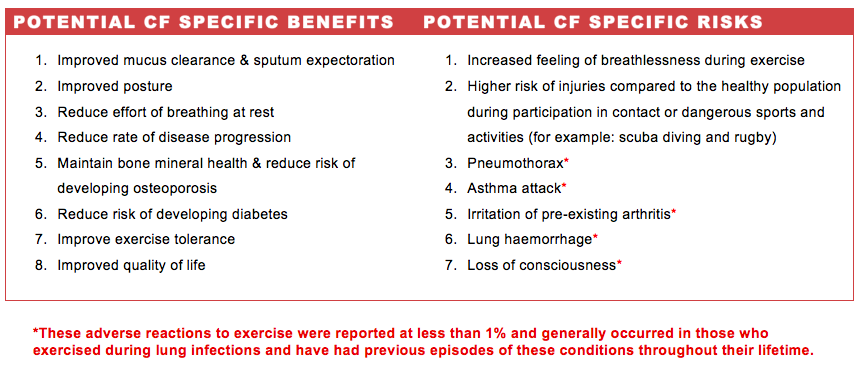

All exercisers should be aware of the benefits and risks involved in their leisure-time physical activity in order to self-motivate and pre-plan for known dangers. Individuals with CF are particularly vulnerable in respect to their reduced pulmonary function and we suggest adopting a preventative strategy, such as supervision and emergency protocols.

In addition to the benefits outlined specifically for those with CF, universal exercise benefits are applicable. For instance, exercise has been shown to generate positive effects on mood and lowers anxiety. Research also tells us that good experiences of physical activity can promote self-efficacy thereby increasing one’s confidence. All of which are psychological benefits that those living with CF may enjoy to experience the same as their healthy peers.

Exercise Prescription[edit | edit source]

Recently, there has been a significant amount of research regarding the use of exercise as “medicine” to benefit individuals living with cystic fibrosis. Such studies are important for determining the physical capacity at which these individuals are capable of enduring. Furthermore, an accumulation and examination of the results allows for clinicians to determine appropriate guidelines specifically designed for individuals with cystic fibrosis.

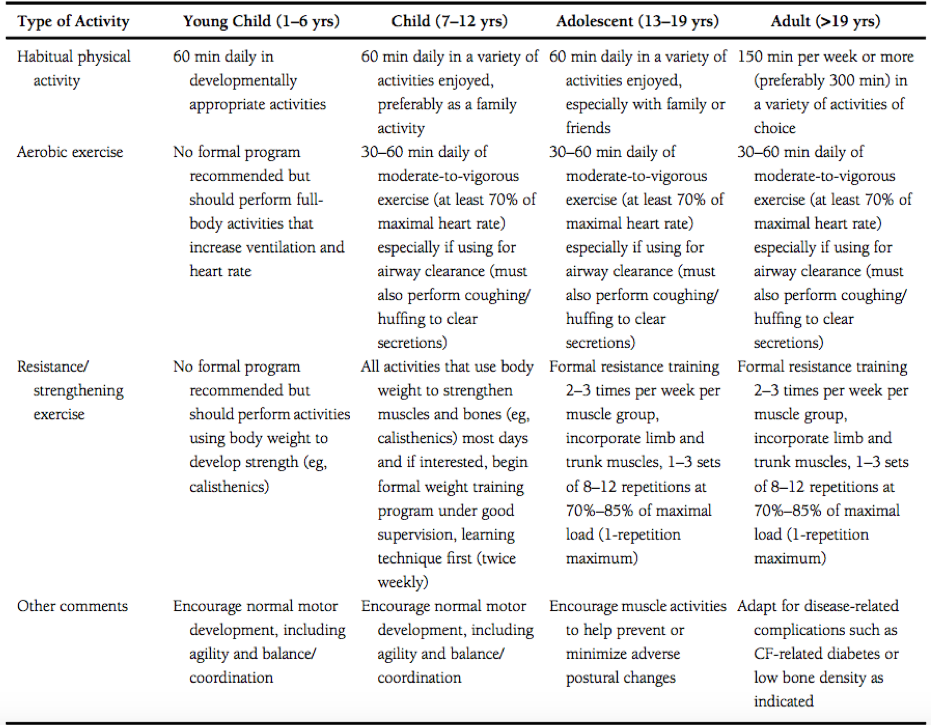

Swisher et al. developed specific exercise prescription for individuals of all ages living with cystic fibrosis, which can be viewed in the table below. It is however important to note that although these guidelines were developed by exercise and medical professionals, the onus is on the individual and their supportive team to adapt the prescription to fit the needs, capabilities and safety of the person performing the activity.

Exercise is often prescribed as a combined treatment for CF with traditional respiratory physiotherapy techniques because movements are able to affect the physiological function of the body. For example, the movement of the body during exercise may help to condition the muscles thereby maintaining proper posture prevent curvatures in the spine that can ultimately lead to compression of the torso, which affects the ability to expand the chest during inhalation. Schindel et al. examined this idea in detail with a gold standard study design, whereby the research suggests that maintaining posture through mobility, stretching and aerobic exercise can positively affect lung function, particularly for those with cystic fibrosis. Furthermore, Pedersen and Saltin explain that the movements produced by exercise can stimulate optimal function of the mucociliary transport system within the lungs to aid in easier clearance of excess mucus due to the disease. With less mucus in the lungs there may be less chance of chest infections as well as better quality of normal breathing experienced. Such improvements in ventilation will allow the body to naturally increase the amount of air available for gaseous exchange in the lungs thereby increasing oxygen into the blood and ultimately successful amending the individual’s oxygen saturation measures (Kriemler et al., 2016). Aside from exercises helping functions directly related to the pulmonary system, it may also be used to decrease the chance of acquiring co-morbidities such as osteoporosis and diabetes.

It seems that half of the battle to exercising is making it fun and enjoyable. The ability to choose the type of activity is one way to give individuals with CF autonomy in their life and leads to greater personal satisfaction, confidence and adherence (Orenstein & Higgins, 2005). This is especially important to implement early because it can help the individual to adopt this behaviour as a long term healthy habit and even encourage continuance throughout one’s life. Another way to bring about intrinsic motivation is to encourage the exerciser with appropriate music. A recent study showed that different types of music might be used to help distract the mind from thoughts about their high level of exertion and even reduce vital signs (Calik-Kutukcu et al., 2016). Both motivational and relaxation music appear to have equal effect regarding these outcomes, therefore it is personal preference as to which sound to listen to (Calik-Kutukcu et al., 2016). This provides the exerciser with another opportunity to participate in the decision-making aspect of exercising.

Check Point: Try these self-assessment questions below[edit | edit source]

- What is the difference between physical activity and exercise?

- How can exercise be used to help the physical function and overall lifestyle of those living with CF?

EMERGING RESEARCH[edit | edit source]

Therapies for Lung Disease[edit | edit source]

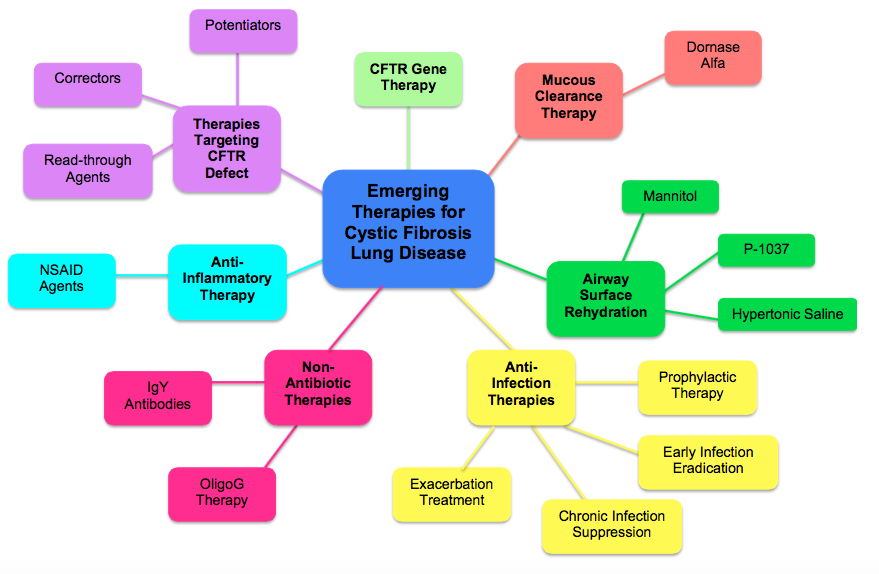

Lung disease associated with Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is the cyclical pattern of mucous retention, infection, inflammation, and tissue damage. There are multiple therapies that address each one of the stages in that pattern (Kreindler, 2010). Below are some of the emerging therapies available for CF patients.

Mucous Clearance Therapies[edit | edit source]

While there are a number of physical techniques for mucous clearance, the emerging drug therapy research provides the CF community with pharmacological advances that create thinner mucous, and hydrate the airway surfaces to encourage easier mucous removal (Kreindler, 2010).

For example, Dornase Alfa, (marketed as Pulmozyme® by Genentech), acts as a mucolytic, which degrades the extracellular DNA that causes thick mucous in the airways of CF patients (Kreindler, 2010). The breakdown of the extracellular DNA helps with airway clearance, and has shown to improve lung function

Airway Surface Rehydration Therapies[edit | edit source]

Hypertonic Saline[edit | edit source]

Contribution to CF airway disease can be associated with increased sodium absorption from the airway surface liquid and the ensuing decrease in airway surface liquid volume (Kreindler, 2010). Inhalation of hypertonic saline can be used to counteract the airway surface liquid decrease by drawing water into the airway lumen (Kreindler, 2010). This type of therapy has shown to improve clearance of mucous, overall lung function, and reduction in pulmonary exacerbation frequency in patient with CF (Kreindler, 2010).

Mannitol[edit | edit source]

Dry-powder Mannitol (Marketed as Bronchitol, Pharmaxis) is an alternative therapy to hypertonic saline (Kreindler, 2010). As a non-absorbable sugar alcohol, Mannitol aids in mucous clearance by rehydrating the airway surface and increasing the volume of airway surface liquid (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). In a Phase III clinical trial, a sustained increase in FEV1 and decrease in pulmonary exacerbations were found, however, adverse effects including cough and coughing with blood occurred (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). From current studies, Mannitol has proven safe for CF patients that are able to tolerate the therapy (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). While the therapy has not been clearly proven to be effective in children, a Phase II clinical trial is underway (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

P-1037[edit | edit source]

CFTR interacts with proteins, including the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) and due to normal inhibitory function loss; there is over-stimulation of ENaC and hyper-absorption of sodium, which leads to the dehydration of the airway surface and mucous (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Currently, there is a Phase II clinical trial progression for P-1037; an inhaled ENaC blocker (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Hyperkalaemia has been noted as a potential side effect of P-1037 due to renal exposure, and therefore, a low dose is required (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Anti-Infective Therapies[edit | edit source]

In Cystic Fibrosis, antibiotics are utilized under four conditions: prophylactically, infection eradication, chronic infection suppression, and exacerbation treatment (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). CF pathogens found in the lungs vary with age, where S. aureus is the most common in infancy, H. influenzae increasing in childhood, and P. aeruginosa being the most common pathogen by adolescence and young adulthood (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Prophylaxis[edit | edit source]

UK and European guidelines currently recommend anti-staphylococcal antibiotics starting at diagnosis until approximately 3 years old as it has proven to reduce methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) incidence, however, clinical outcome improvements have not been confirmed (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

In contrast to this, USA recommendations are currently against the use of prophylactic anti-staphylococcal antibiotics due to results in one trial that reported increased pseudomonas infection rates (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Further clinical trials of quality need to be completed to resolve the contrast between these recommendations for prophylactic therapy (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Early Infection Eradication[edit | edit source]

In terms of infection, P. aeruginosa is the organism of most concern, due to the high risk it will become a chronic infection if not treated aggressively (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Lung function decline can be associated with the inflammatory reaction of a chronic infection (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Early eradication programs are comprised of +/- systemic antibiotics, but can vary between countries (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Inhaled tobramycin is used initially in North America, however, a multicentre trial in Europe is analyzing whether IV or oral antibiotics administered with nebulized colistin are of higher quality (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Chronic Infection Suppression[edit | edit source]

The treatment emphasis changes from infection eradication to infection suppression once it becomes a chronic condition, and the intention is to decrease inflammation (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Current research has concentrated on antimicrobial delivery through inhalation, which allows for high concentrations of the drug to be transported to the infection site, all while decreasing adverse effects and optimizing bacterial elimination (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). However, some adverse effects have been recognized, such as possible bronchospasm, displeasing taste, and length of time required to administer the drug (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Currently, tobramycin, colistin, and aztreonam are nebulized antibiotics used to treat P. aeruginosa, and are often used in an alternating approach (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Patients with chronic P. aeruginosa were treated with aztreonam for inhalation solution (AZLI) in an 18-month safety and efficacy open-label trial, and results showed decreased bacterial burden (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Another open-label trial compared the use of nebulized tobramycin with AZLI, and found significant lung function improvement and decreased pulmonary exacerbations over three course treatments in the AZLI group compared to the tobramycin group (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). In this trial, AZLI when compared to tobramycin, showed an equal reduction in P. aeruginosa and was also well tolerated by the patients (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

In other research, many additional agents are being investigated. A trial for a once-a-day liposomal formula of amikacin is underway, and thought to be beneficial as the drug would be activated at the site of infection due to the liposome breakdown by bacterial rhamnolipids (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Recently, levofloxacin inhalation solution (MP-376) has proven to be equally as effective as tobramycin, and well-tolerated by patients (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Exacerbation Treatment[edit | edit source]

Pulmonary exacerbations are groupings of symptoms and decline in lung function and depending on the severity, are treated using oral or IV antibiotics (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Patients will often receive a 2-week course of IV antibiotic, but research from one study has shown that maximal lung function is achieved following 10 days, and there is no advantage to continuing treatment past the 10 day mark. The CF Foundation in the USA has focused largely on this subject in a multicentre research programme (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Non-antibiotic Treatment Options to Bacterial Infection[edit | edit source]

OligoG[edit | edit source]

In CF airways, chronic P. aeruginosa grows in a biofilm, which consists of airway mucins, exopolysaccharide, and a matrix of neutrophil DNA, and is largely resistant to antibiotic treatment (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). OligoG is a sea-weed-derived alginate oligosaccharide formulated into a dry-powder agent, which obtains both anti-mucolytic and anti-biofilm characteristics and is currently in phase II trials (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

IgY Antibodies[edit | edit source]

In a small clinical trial, it is suggested that protection against P. aeruginosa could be gained via IgY acquired from immunized hen eggs, and there is a multicentre trial underway which investigates the IgY antibody delivered as a gargle solution (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Anti-Inflammatory Therapies[edit | edit source]

Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents[edit | edit source]

Ibuprofen has shown some improvement in younger patients with milder CF, however, current research has shown difficulties with dosing, where low-dose ibuprofen can encourage inflammation, and high-dose ibuprofen causes adverse side effects (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). In a Cochrane review completed recently, ibuprofen in higher doses showed slower lung function decline and decreased hospital stay, but long-term adverse effects were not investigated (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Therapies Targeting the CFTR Defect[edit | edit source]

Research targeting the CFTR defect focuses on three different groups of drug therapy which include potentiators, correctors, and read-through agents (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). With potentiator drug therapy, the CFTR channel activity is enhanced so long as it is located correctly (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Corrector drug therapy is used to repair defects that may include misfolding of the F508del protein, which allows cell surface trafficking (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Lastly, read-through agents produce a full length protein by permitting a ribosome to dismiss a premature termination codon (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). In current research, these three types of drug therapies have either advanced to or through clinical trials (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Potentiators[edit | edit source]

Cystic Fibrosis treatment progress in more recent years has gained strength due to the development of ivacaftor, where the most common CF gene mutation (Asp551Gly (G551D)) has seen positive results in clinical trial with this agent (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Improvements were seen in exacerbation rate, quality of life, weight, and FEV1 (~10% absolute improvement) during the ivacaftor trial, which has led to a license for use in CF patients aged 6 years and older (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Further to this, a clinical trial in children ages 2-5 found similar results in sweat chloride; the CFTR biomarker (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Correctors[edit | edit source]

In a 2012 study, Lumacaftor (VX-809) was found to restore CFTR function to roughly 15% of CFTR level in vitro, however, this did not show significant improvements in F508del patients (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Further to this, single-agent ivacaftor did not show significant changes, which was hypothesized to be a consequence of limited CFTR available at the cell surface (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Due to this, there has been investigation into the advantage of combined lumicaftor/ivacaftor, and a phase III traffic and transport trial resulted in FEV1 improvements and decreased pulmonary exacerbations (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). There is a phase III trial underway in a range of mutations for a new corrector, VX-661, which will be in combination with ivacaftor, however, there is a concern of cost, which may cause problems for national healthcare systems, and there is more research needed in order to support and manage this issue (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

Read-through Agents[edit | edit source]

Production of a full length CFTR can be a result of Ataluren, which promotes ribosomal read-through of premature termination codons (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). In a phase III trial, there were no significant results seen between the ataluren and placebo groups, however, notable benefits were seen in patients who received aminoglycoside antibiotics through inhalation (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). There is a second phase III trial underway in patients 6 years and older not receiving aminoglycoside antibiotics (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

There has been conditional approval of read-through agents granted for other inherited diseases, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, as read-through agents consist of therapeutic potential in stop mutation diseases (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

CFTR Gene Therapy[edit | edit source]

There have been over 20 clinical trials in gene therapy since the CFTR gene was discovered, however many of these trials have focused on molecular or electrophysiological defects and single dose (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Recently, the UK CF Gene Therapy Consortium (GTC) has coordinated a phase IIb clinical trial of liposomal CFTR gene therapy where patients were administered nebulized doses, every month, for one year, or a placebo (Edmondson and Davies, 2016). Results showed that patients receiving the intervention had FEV1 stabilization, and there was a 3.7% statistical difference between intervention and placebo groups and further trials will investigate whether higher or more frequent doses can make additional improvements (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

There is another approach to gene therapy, where the aim is to correct opposed to replace the gene, and a phase Ib clinical trial of nebulized mRNA repair molecule QR010 is currently in progress (Edmondson and Davies, 2016).

ACADEMIC INSTITUTION INVOLVEMENT[edit | edit source]

Cystic fibrosis should not stop your child enjoying a full and rewarding school experience. Compromises may need to be found, and adjustments made, but working closely with the school and the CF tem will help to ensure that your child’s education is not limited by CF.

Questions to consider when looking for a school:

- Does the school have experience with children with CF?

- Are there any other children with cystic fibrosis at the school?

- My child has to take enzyme supplements with snacks and meals, what is your policy on this?

- My child needs a high fat snack between meals, how will this work with your healthy eating policy?

- If my child needs to do physiotherapy exercises, would you be able to accommodate this?

Think about creating an individual healthcare plan:

When starting school, it is a good common sense idea for your child to have a individual healthcare plan (Well at School 2016). These are developed to help school staff to understand what a particular medical condition means for a child at school and should include information about CF, how it affects you child, treatment details, dietary needs and contact details. Many schools have their own individual healthcare plan templates but if not, a healthcare plan template is available on the cystic fibrosis website

Communication

[edit | edit source]

Communication is key to ensuring children with CF are appropriately cared for and all relevant staff should know about your child's needs. Ensure the school keeps you informed about changes in your child's symptoms, missed creon doses etc. And you should decide how you want this communicated eg. Communication books (cystic fibrosis Trust, 2015).

Infection Risk

[edit | edit source]

Coughs and Colds

Avoiding infection is a very common and valid worry and risk can be minimised by encouraging effective infection control measures and asking staff to keep children with coughs and colds apart, where possible, from your child.

Environment

- Certain environments-mud, stagnant water, hate that have fungi which can be harmful to children with CF

- This can impact on playing outdoors etc.

- Some minor practical adjustments can be made- teachers can ensure water is always fresh, the table is cleaned and dried every day and there is fresh sand for sand play (Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2015).

Creon[edit | edit source]

- Schools have their own systems of storing and administering

- Ensure to communicate effectively with the school to decide what system will work for your child

- Getting creon dose right can be difficult, particularly when a child first starts school

- Ensure to keep in touch with the school about your child's eating habits and creon dose.

- Your child may be asked about their creon by other children. Speak to the school about whether you would like your child to take their creon in private. Many parents don’t want their child to feel that CF is something to be ashamed of so they don’t hide the treatment.

Diet[edit | edit source]

At school this is usually an Option of school meals or a packed lunch. The school can make the menu available to you and the CF dietitian will be able to help work out the creon doses with you. Your child is most likely to need other snacks during the day and this should be discussed with the school.

Attendance[edit | edit source]

Many parents worry that their child will be penalised for absence. A lot of schools have absence policies in place and rewards for 100% attendance and for children with CF it seems like they are setup to fail on this one. Speak to the head teacher as they are most likely to be flexible on this. Liaise with the school about the best arrangement for your child and their attendance. Parents have said that sometimes it is difficult to get to school on time, particularly if their child is struggling with mucus and physiotherapy is taking longer- Schools are usually sympathetic about this and feel better that the child comes to school late rather than not at all (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2016).

Top tips from parents[edit | edit source]

TRANSITION FROM PAEDIATRIC TO ADULT CARE[edit | edit source]

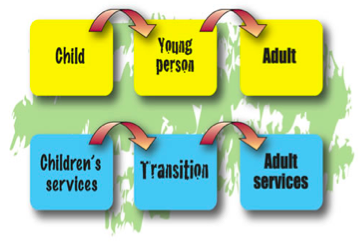

What is transition in Cystic Fibrosis?

Transition in CF has been described as “a purposeful, planned preparation of patients, families and caregivers for transfer of the patient to an adult program” (Flume, 2001).

Please click on this link to watch a Cystic Fibrosis transition film:

www.rbht.nhs.uk/patients/condition/cystic-fibrosis/cystic-fibrosis-transition/transition-film/

Need For Transfer[edit | edit source]

Why do children need to transfer to an adult service?

Cystic fibrosis is no longer a condition the only affects children. Individuals with cystic fibrosis have a greater lifespan, and there are currently more adults with cystic fibrosis than children.

There is a requirement to react to the developing maturity of adolescents with cystic fibrosis. They must be involved in decisions regarding their care and treatment. This should begin as soon as possible in the paedriatric service and continue within the adult service.

Adolescents may not realise the need for transfer to begin with but it will become relevant to them as they mature, gain independence, interests and develop new relationships.

They will have to deal with managing their health and treatment along with education, career and relationships in the future. Therefore, it is necesssary that they start to understand how their feelings and attitude about their health and treatment will infuence their future well-being (Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2013).

Differences Between Services[edit | edit source]

What differences are there between the paediatric and the adult CF services?

The paediatric service team work mainly with the parents rather than the child with CF. The parents are shown how to care for their child and manage their treatment. The childs decisions are made for them rather than with them. However, this gradually changes as the child develops and they will activily engage in making decisions with regard to their care (Fegran et al. 2013).

The adult service works directly with the individual with CF. The individuals should now be involved in the planning and delivery of health services under the guidance of the CF team (Oppong-Odiseng, 1997; Dodd, 1996; DH, 2006). The team aims to incorporate the treatment with the patient’s lifestyle and give emotional support to the individual as issues arise.

Parents and carers may still remain involved, however their role becomes supportive once the individual has transferred.

Timing[edit | edit source]

When should the discussion of transition begin?

The discussion of transition should begin at least a year before the transfer to adult services occurs. This provides the individual and their parent/caregiver with sufficient time to consider feelings and settle any worries either may have (Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2013).

When does the transfer to adult services happen?

The timing of transfer is different for individuals and is dependent on their requirements. However, to prevent premature or late transfer, it is advised that transfer should occur between the ages of 14 and 18 (Conway, 2004).

Barriers[edit | edit source]

Transition to adult care for young people with CF can be ineffective when there is:

- A lack of support of the transition process by any of the participants, which include the health care teams, adolescents and families, and the health care system;

- Limited preparation for transition;

- Lack of regular communication between participants (Towns and Bell, 2010).

Effective Transitioning[edit | edit source]

Preparation, planning and communication by every participant (healthcare team, family and the individual) are key for a successful transition. This could be through ensuring the individual has been educated about CF and has the skills training to manage their long-term condition. If not, it is important to contact the relevant CF team member to address any concerns.

Specific CF clinics were another componenet found to be important for successful transitions. Your CF team should provide you with the relevant information about these clinics.

It has been shown that young people with CF experience an effective transition when these is an are the opportunity for a joint meeting with the paediatric and adult services, a visit to the adult service before transition and having their first appointment made for them. If this is not the case, this should be highlighted with the CF team to ensure optimal transition (Craig et al. 2007, Steinbeck & Brodie 2006).

Expected Changes[edit | edit source]

What changes may I expect as a parent?

Adolescents gradually become more independent and they are capable of making important decisions for themselves such as education or career path. However, they may still require support in more difficult choices such as ones involving medical treatments and surgeries.

It can be difficult as a parent to step back and allow adolescents to take charge of their care. Adolescents may be asked for advice, however this may be ignored. It is important to remember that all parents experience this as their children mature.

It is important to be able to take a step back and discuss with the child to what is it they want. They might want to continue discussing health issues as they arise but might not want to be told what to do. The role of advisor will now change to that of a counselor.

You may not always agree with the adolescents’ opinions, however it must be respected. This can be challenging for a parent but most adult services are familiar with these problems and are there for support during difficult times (Cystic Fibrosis Trust, 2013).

Role of Physiotherapists[edit | edit source]

What are Physiotherapists’ roles in transition?

- To communicate with the adult service about each individual’s specific treatment program to ensure effective transition.

- To promote self-management (hyperlink to “what is self-management?’ below) and give information about the adult service to the individual.

- To remain in contact with the adult service for the first year after transfer to adult services to ensure optimum healthcare.

- To listen to what the patient has to say and support them and their family.

- To respect the individuals decision whatever it may be (Button et al. 2016).

Further Web Resources on Transition[edit | edit source]

cf.kch.nhs.uk/transition/what_we_do/

Check Point: Try these self-assessment questions below[edit | edit source]

Checklist to ensure you understand transition

- Do you understand what is meant by transition in CF?

- Why does transition happen?

- Do you know the differences between child and adult services?

- When does transition begin?

- When does transfer to adult services happen?

Checklist to support effective transition for the individual with CF

- Have they been offered the opportunity for a joint meeting between both services?

- Have they visited the adult service before transfer?

- Has the first appointment been arranged for them in the adult service?

- Do you and the individual with CF understand what is meant by self-management?

- Are they self-managing their Physiotherapy techniques appropriate to their age?

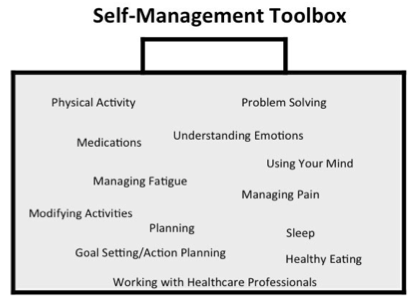

SELF-MANAGEMENT

[edit | edit source]

What is self-management?

Self-management can be described as helping individuals and their families to monitor and change treatment requirements for their condition, and manage the effect it has on their lives. The goal is to achieve optimal health and to fit their treatment plan into their everyday lives around a flexible management plan. It is the role of the entire healthcare team to support this (Newman, 2004).

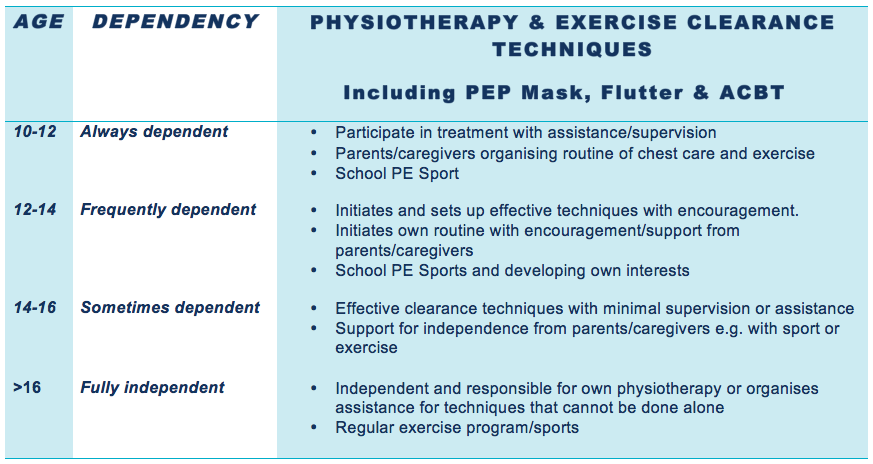

When should individuals with Cystic Fibrosis be able to self manage their physiotherapy and exercise clearance technique?

CONCLUSION[edit | edit source]

Planning for the Future[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

REFERENCES[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.