Otitis Media: Difference between revisions

Mohit Chand (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Mohit Chand (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

Acute otitis media is the second most common pediatric diagnosis in the emergency department, following upper respiratory infections. Although otitis media can occur at any age, it is most commonly seen between the ages of '''6 to 24 months'''.<ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6572929/] Meherali S, Campbell A, Hartling L, Scott S. Understanding Parents' Experiences and Information Needs on Pediatric Acute Otitis Media: A Qualitative Study. J Patient Exp. 2019 Mar;6(1):53-61.</ref> | Acute otitis media is the second most common pediatric diagnosis in the emergency department, following upper respiratory infections. Although otitis media can occur at any age, it is most commonly seen between the ages of '''6 to 24 months'''.<ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6572929/] Meherali S, Campbell A, Hartling L, Scott S. Understanding Parents' Experiences and Information Needs on Pediatric Acute Otitis Media: A Qualitative Study. J Patient Exp. 2019 Mar;6(1):53-61.</ref> | ||

== Etiology == | == Etiology == | ||

Revision as of 10:14, 25 November 2023

Original Editor - Mohit Chand[edit | edit source]

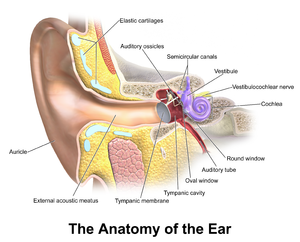

Acute otitis media is defined as an infection of the middle ear space.

It is a spectrum of diseases that includes:[1]

- Acute otitis media (AOM): The rapid onset of signs and symptoms of inflammation of the middle ear

- Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM): OME persisting for ≥3 month from the date of onset (if known) or from the date of diagnosis (if onset unknown)

- And Otitis media with effusion (OME): The presence of fluid in the middle ear without signs or symptoms of acute ear infection (AOM)

Acute otitis media is the second most common pediatric diagnosis in the emergency department, following upper respiratory infections. Although otitis media can occur at any age, it is most commonly seen between the ages of 6 to 24 months.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Otitis media is a multifactorial disease. Infectious, allergic, and environmental factors contribute to otitis media.

The causes and risk factors include:

- Decreased immunity due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), diabetes, and other immuno-deficiencies.

- Genetic predisposition[3]

- Mucins that include abnormalities of this gene expression, especially upregulation of MUC5B

- Anatomic abnormalities of the palate and tensor veli palatini

- Ciliary dysfunction

- Cochlear implants[4]

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Bacterial pathogens, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, and Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis are responsible for more than 95%

- Viral pathogens such as respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, rhinovirus, and adenovirus[5]

- Allergies

- Lack of breastfeeding[6]

- Passive smoke exposure[7]

- Daycare attendance

- Lower socioeconomic status

- Family history of recurrent AOM in parents or siblings

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Otitis media is a global problem and is found to be slightly more common in males than in females. The specific number of cases per year is difficult to determine due to the lack of reporting and different incidences across many different geographical regions. The peak incidence of otitis media occurs between six and twelve months of life and declines after age five.[8]

Approximately 80% of all children will experience a case of otitis media during their lifetime, and between 80% and 90% of all children will experience otitis media with an effusion before school age.

Otitis media is less common in adults than in children, though it is more common in specific sub-populations such as those with a childhood history of recurrent OM, cleft palate, immunodeficiency or immunocompromised status, and others.[9]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Otitis media begins as an inflammatory process following a viral upper respiratory tract infection involving the mucosa of the nose, nasopharynx, middle ear mucosa, and Eustachian tubes.

Due to the constricted anatomical space of the middle ear, the edema caused by the inflammatory process obstructs the narrowest part of the Eustachian tube leading to a decrease in ventilation. This leads to a cascade of events resulting in an increase in negative pressure in the middle ear, increasing exudate from the inflamed mucosa, and buildup of mucosal secretions, which allows for the colonization of bacterial and viral organisms in the middle ear. The growth of these microbes in the middle ear then leads to suppuration and, eventually, frank purulence in the middle ear space. This is demonstrated clinically by a bulging or erythematous tympanic membrane and purulent middle ear fluid.[10]

This must be differentiated from chronic serous otitis media (CSOM), which presents with thick, amber-colored fluid in the middle ear space and a retracted tympanic membrane on otoscopic examination. Both will yield decreased TM mobility on tympanometry or pneumatic otoscopy.

Several risk factors can predispose children to develop acute otitis media. The most common risk factor is a preceding upper respiratory tract infection. Other risk factors include male gender, adenoid hypertrophy (obstructing), allergy, daycare attendance, environmental smoke exposure, pacifier use, immunodeficiency, gastroesophageal reflux, parental history of recurrent childhood OM, and other genetic predispositions.[11]

Histopathology[edit | edit source]

Histopathology varies according to disease severity.

Acute purulent otitis media (APOM) is characterized by edema and hyperemia of the subepithelial space, which is followed by the infiltration of polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes. As the inflammatory process progresses, there is mucosal metaplasia and the formation of granulation tissue. After five days, the epithelium changes from flat cuboidal to pseudostratified columnar with the presence of goblet cells.

In serous acute otitis media (SAOM), inflammation of the middle ear and the eustachian tube has been identified as the major precipitating factor. Venous or lymphatic stasis in the nasopharynx or the eustachian tube plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of AOM. Inflammatory cytokines attract plasma cells, leukocytes, and macrophages to the site of inflammation. The epithelium changes to pseudostratified, columnar, or cuboidal. Hyperplasia of basal cells results in an increased number of goblet cells in the new epithelium.[12]

In practice, biopsy for histology is not performed for OM outside of research settings.

Clinical Features[edit | edit source]

In adults, an upper respiratory tract infection or exacerbation of seasonal allergic rhinitis often precedes the onset of AOM. In adults, AOM is typically unilateral and is associated with otalgia (ear pain) and decreased or muffled hearing. The pain may be mild, moderate, or severe. If the tympanic membrane has ruptured, the patient may report a sudden relief of pain, possibly accompanied by purulent otorrhea.

Dysequilibrium may be present but is described infrequently. Conductive hearing loss, which may occur due to the presence of middle ear fluid, is usually transient.

Other symptoms, such as high fever, severe pain behind the ear, or facial paralysis, suggest unusual complications.[31]

Many children with otitis media can present with non-specific signs and symptoms, which can make the diagnosis challenging. These symptoms include pulling or tugging at the ears, irritability, headache, disturbed or restless sleep, poor feeding, anorexia, vomiting, or diarrhea. Approximately two-thirds of the patients present with fever, which is typically low-grade.

The diagnosis of otitis media is primarily based on clinical findings combined with supporting signs and symptoms as described above. No lab test or imaging is needed. According to guidelines set forth by the American Academy of Pediatrics, evidence of moderate to severe bulging of the tympanic membrane or new onset of otorrhea not caused by otitis externa or mild tympanic membrane (TM) bulging with recent onset of ear pain or erythema is required for the diagnosis of acute otitis media. These criteria are intended only to aid primary care clinicians in the diagnosis and proper clinical decision-making but not to replace clinical judgment.[13]

Otoscopic examination should be the first and most convenient way of examining the ear and will yield the diagnosis to the experienced eye.

In AOM, the TM may be erythematous or normal, and there may be fluid in the middle ear space. In suppurative OM, there will be obvious purulent fluid visible and a bulging TM. The external ear canal (EAC) may be somewhat edematous, though significant edema should alert the clinician to suspect otitis externa (outer ear infection, AOE), which may be treated differently. In the presence of EAC edema, it is paramount to visualize the TM to ensure it is intact. If there is an intact TM and a painful, erythematous EAC, ototopical drops should be added to treat AOE. This can exist in conjunction with AOM or independent of it, so visualization of the middle ear is paramount. If there is a perforation of the TM, then the EAC edema can be assumed to be reactive, and ototopical medication should be used, but an agent approved for use in the middle ear, such as ofloxacin, must be used, as other agents can be ototoxic.[14]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of otitis media should always begin with a physical exam and the use of an otoscope, ideally a pneumatic otoscope.[15]

Laboratory Studies:

Laboratory evaluation is rarely necessary. A full sepsis workup in infants younger than 12 weeks with fever and no obvious source other than associated acute otitis media may be necessary. Laboratory studies may be needed to confirm or exclude possible related systemic or congenital diseases.

Imaging Studies:

Imaging studies are not indicated unless intra-temporal or intracranial complications are a concern.[16]

- When an otitis media complication is suspected, computed tomography of the temporal bones may identify mastoiditis, epidural abscess, sigmoid sinus thrombophlebitis, meningitis, brain abscess, subdural abscess, ossicular disease, and cholesteatoma.

- Magnetic resonance imaging may identify fluid collections, especially in the middle ear collections.

Tympanocentesis:

Tympanocentesis may be used to determine the presence of middle ear fluid, followed by culture to identify pathogens.

Tympanocentesis can improve diagnostic accuracy and guide treatment decisions but is reserved for extreme or refractory cases.[17]

Other Tests:

Tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry may also be used to evaluate for middle ear effusion.[18]

Treatment / Management[edit | edit source]

Once the diagnosis of acute otitis media is established, the goal of treatment is to control pain and treat the infectious process with antibiotics.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen can be used to achieve pain control. There are controversies about prescribing antibiotics in early otitis media, and the guidelines may vary by country, as discussed above. Watchful waiting is practiced in European countries with no reported increased incidence of complications. However, watchful waiting has not gained wide acceptance in the United States. If there is clinical evidence of suppurative AOM, however, oral antibiotics are indicated to treat this bacterial infection, and high-dose amoxicillin or a second-generation cephalosporin are first-line agents.

If there is a TM perforation, treatment should proceed with ototopical antibiotics safe for middle-ear use, such as ofloxacin, rather than systemic antibiotics, as this delivers much higher concentrations of antibiotics without any systemic side effects.[19]

When a bacterial etiology is suspected, the antibiotic of choice is high-dose amoxicillin for ten days in both children and adult patients who are not allergic to penicillin. Amoxicillin has good efficacy in the treatment of otitis media due to its high concentration in the middle ear.

Systemic steroids and antihistamines have not been shown to have any significant benefits.

Patients who have experienced four or more episodes of AOM in the past twelve months should be considered candidates for myringotomy with tube (grommet) placement, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Recurrent infections requiring antibiotics are clinical evidence of Eustachian tube dysfunction, and placement of the tympanostomy tube allows ventilation of the middle ear space and maintenance of normal hearing. Furthermore, should the patient acquire otitis media while a functioning tube is in place, they can be treated with ototopical antibiotic drops rather than systemic antibiotics.[20]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The following conditions come under the differential diagnosis of otitis media:[21]

- Cholesteatoma

- Fever in the infant and toddler

- Fever without a focus

- Hearing impairment

- Pediatric nasal polyps

- Nasopharyngeal cancer

- Otitis externa

- Human parainfluenza viruses (HPIV) and other parainfluenza viruses

- Passive smoking and lung disease

- Pediatric allergic rhinitis

- Pediatric bacterial meningitis

- Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux

- Pediatric Haemophilus influenzae infection

- Pediatric HIV infection

- Pediatric mastoiditis

- Pediatric pneumococcal infections

- Primary ciliary dyskinesia

- Respiratory syncytial virus infection

- Rhinovirus (RV) infection (common cold)

- Teething

Resources[edit | edit source]

Otitis Media in Infants and Children by Charles D. Bluestone, MD

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Rettig E, Tunkel DE. Contemporary concepts in management of acute otitis media in children. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014 Oct;47(5):651-72. [1]

- ↑ [2] Meherali S, Campbell A, Hartling L, Scott S. Understanding Parents' Experiences and Information Needs on Pediatric Acute Otitis Media: A Qualitative Study. J Patient Exp. 2019 Mar;6(1):53-61.

- ↑ Mittal R, Robalino G, Gerring R, Chan B, Yan D, Grati M, Liu XZ. Immunity genes and susceptibility to otitis media: a comprehensive review. J Genet Genomics. 2014 Nov 20;41(11):567-81.[3]

- ↑ Vila PM, Ghogomu NT, Odom-John AR, Hullar TE, Hirose K. Infectious complications of pediatric cochlear implants are highly influenced by otitis media. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jun;97:76-82.[4]

- ↑ Seppälä E, Sillanpää S, Nurminen N, Huhtala H, Toppari J, Ilonen J, Veijola R, Knip M, Sipilä M, Laranne J, Oikarinen S, Hyöty H. Human enterovirus and rhinovirus infections are associated with otitis media in a prospective birth cohort study. J Clin Virol. 2016 Dec;85:1-6. [5]

- ↑ Ardiç C, Yavuz E. Effect of breastfeeding on common pediatric infections: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2018 Apr 01;116(2):126-132.[6]

- ↑ Strachan DP, Cook DG. Health effects of passive smoking. 4. Parental smoking, middle ear disease and adenotonsillectomy in children. Thorax. 1998 Jan;53(1):50-6.[7] Jones LL, Hassanien A, Cook DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Parental smoking and the risk of middle ear disease in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012 Jan;166(1):18-27. [8]

- ↑ Usonis V, Jackowska T, Petraitiene S, Sapala A, Neculau A, Stryjewska I, Devadiga R, Tafalla M, Holl K. Incidence of acute otitis media in children below 6 years of age seen in medical practices in five East European countries. BMC Pediatr. 2016 Jul 26;16:108.[9]

- ↑ Schilder AG, Chonmaitree T, Cripps AW, Rosenfeld RM, Casselbrant ML, Haggard MP, Venekamp RP. Otitis media. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016 Sep 08;2(1):16063.[10]

- ↑ Fireman P. Otitis media and eustachian tube dysfunction: connection to allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997 Feb;99(2):S787-97.[11] Fireman P. Eustachian tube obstruction and allergy: a role in otitis media with effusion? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985 Aug;76(2 Pt 1):137-40.[12]

- ↑ Kraemer MJ, Richardson MA, Weiss NS, Furukawa CT, Shapiro GG, Pierson WE, Bierman CW. Risk factors for persistent middle-ear effusions. Otitis media, catarrh, cigarette smoke exposure, and atopy. JAMA. 1983 Feb 25;249(8):1022-5. [13]

- ↑ Meyerhoff WL, Giebink GS. Panel discussion: pathogenesis of otitis media. Pathology and microbiology of otitis media. Laryngoscope. 1982 Mar;92(3):273-7.[14]

- ↑ Siddiq S, Grainger J. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media: American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines 2013. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2015 Aug;100(4):193-7.[15]

- ↑ Marchisio P, Galli L, Bortone B, Ciarcià M, Motisi MA, Novelli A, Pinto L, Bottero S, Pignataro L, Piacentini G, Mattina R, Cutrera R, Varicchio A, Luigi Marseglia G, Villani A, Chiappini E., Italian Panel for the Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children. Updated Guidelines for the Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children by the Italian Society of Pediatrics: Treatment. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Dec;38(12S Suppl):S10-S21.[16] Moazzami B, Mohayeji Nasrabadi MA, Abolhassani H, Olbrich P, Azizi G, Shirzadi R, Modaresi M, Sohani M, Delavari S, Shahkarami S, Yazdani R, Aghamohammadi A. Comprehensive assessment of respiratory complications in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020 May;124(5):505-511.e3.[17] Kaur R, Czup K, Casey JR, Pichichero ME. Correlation of nasopharyngeal cultures prior to and at onset of acute otitis media with middle ear fluid cultures. BMC Infect Dis. 2014 Dec 05;14:640. [18]

- ↑ Chiappini E, Ciarcià M, Bortone B, Doria M, Becherucci P, Marseglia GL, Motisi MA, de Martino M, Galli L, Licari A, De Masi S, Lubrano R, Bettinelli M, Vicini C, Felisati G, Villani A, Marchisio P., Italian Panel for the Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children. Updated Guidelines for the Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children by the Italian Society of Pediatrics: Diagnosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Dec;38(12S Suppl):S3-S9.[19] Homme JH. Acute Otitis Media and Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: A Review for the General Pediatric Practitioner. Pediatr Ann. 2019 Sep 01;48(9):e343-e348.[20]

- ↑ Penido Nde O, Borin A, Iha LC, Suguri VM, Onishi E, Fukuda Y, Cruz OL. Intracranial complications of otitis media: 15 years of experience in 33 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005 Jan;132(1):37-42.[21] Mattos JL, Colman KL, Casselbrant ML, Chi DH. Intratemporal and intracranial complications of acute otitis media in a pediatric population. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014 Dec;78(12):2161-4. [22]

- ↑ Vayalumkal J, Kellner JD. Tympanocentesis for the management of acute otitis media in children: a survey of Canadian pediatricians and family physicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 Oct;158(10):962-5. [23] Schaad UB. Predictive value of double tympanocentesis in acute otitis media. Pharmacotherapy. 2005 Dec;25(12 Pt 2):105S-10S.[24]

- ↑ Lampe RM, Weir MR, Spier J, Rhodes MF. Acoustic reflectometry in the detection of middle ear effusion. Pediatrics. 1985 Jul;76(1):75-8.[25]

- ↑ Chiappini E, Ciarcià M, Bortone B, Doria M, Becherucci P, Marseglia GL, Motisi MA, de Martino M, Galli L, Licari A, De Masi S, Lubrano R, Bettinelli M, Vicini C, Felisati G, Villani A, Marchisio P., Italian Panel for the Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children. Updated Guidelines for the Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children by the Italian Society of Pediatrics: Diagnosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Dec;38(12S Suppl):S3-S9.[26]

- ↑ Marchica CL, Dahl JP, Raol N. What's New with Tubes, Tonsils, and Adenoids? Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2019 Oct;52(5):779-794. [27]

- ↑ Abdelaziz AA, Sadek AA, Talaat M. Differential Diagnosis of Post Auricular Swelling with Mastoid Bone Involvement. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 Nov;71(Suppl 2):1374-1376.[28] Suri NA, Meehan CW, Melwani A. A Healthy Toddler With Fever and Lethargy. Pediatrics. 2019 May;143(5)[29] Dorner RA, Ryan E, Carter JM, Fajardo M, Marsden L, Fricchione M, Higgins A. Gradenigo Syndrome and Cavitary Lung Lesions in a 5-Year-Old With Recurrent Otitis Media. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2017 Sep 01;6(3):305-308.[30]