Myasthenia Gravis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [http://www.physio-pedia.com/User:Wendy_Walker Wendy Walker] | '''Original Editor '''- [http://www.physio-pedia.com/User:Wendy_Walker Wendy Walker] | ||

'''Lead Editors''' | '''Lead Editors''' | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

= Historical Aspect = | |||

The first reported case of MG is likely to be that of the Native American Chief Opechancanough, who died in 1664. It was described by historical chroniclers from Virginia as “the excessive fatigue he encountered wrecked his constitution; his flesh became macerated; the sinews lost their tone and elasticity; and his eyelids were so heavy that he could not see unless they were lifted up by his attendants… he was unable to walk; but his spirit rising above the ruins of his body directed from the litter on which he was carried by his Indians”. In 1672, the English physician Willis first described a patient with “fatigable weakness” involving ocular and bulbar muscles described by his peers as “spurious palsy.” In 1877, Wilks (Guy’s Hospital, London) described the case of a young girl after pathological examination as “bulbar paralysis, fatal, no disease found". In 1879, Wilhelm Erb (Heidelberg, Germany) described three cases of myasthenia gravis in the first paper dealing entirely with this disease, whilst bringing attention to features of bilateral ptosis, diplopia, dysphagia, facial paresis, and weakness of neck muscles. In 1893, Samuel Goldflam (Warsaw, Poland) described three cases with complete description of myasthenia and also analyzed the varying presentations, severity, and prognosis of his cases. Due to significant contributions of Wilhelm Erb and later of Samuel Goldflam, the disease was briefly known as “Erb’s disease” and later for a brief time, it was called “Erb-Goldflam syndrome”. | |||

In 1895, Jolly, at the Berlin Society meeting, described two cases under the title of “myasthenia gravis pseudo-paralytica”. The first two words of this syndrome gradually got accepted as the formal name of this disorder. He also demonstrated a phenomenon, that later came to be known as “Mary Walker effect” after she herself observed and described the same finding in 1938. This was reported as “if you stimulate one group of muscles to exhaustion, weakness is apparent in muscles that are not stimulated; an evidence of a circulating factor causing neuromuscular weakness” | |||

In 1934, Mary Walker realized that MG symptoms were similar to those of curare poisoning, which was treated with physostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor. She demonstrated that physostigmine promptly improved myasthenic symptoms. In 1937, Blalock reported improvement in myasthenic patients after thymectomy. Following these discoveries, cholinesterase inhibitor therapy and thymectomy became standard and accepted forms of treatment for MG. | |||

In 1959-1960, Nastuk et al. and Simpson independently proposed that MG has autoimmune etiology. In 1973, Patrick and Lindstrom were able to induce experimental autoimmune MG (EAMG) in a rabbit model using muscle-like acetylcholine receptor (AChR) immunization. In the 1970s prednisone and azathioprine were introduced as treatment modalities for MG followed by plasma exchange that was introduced for acute treatment of severe MG, all supporting the autoimmune etiology. | |||

= Definition = | = Definition = | ||

| Line 52: | Line 62: | ||

One study showed clear benefit from a strength training exercise programme for a group of patients with mild to moderate MG<ref>Lohi EL1, Lindberg C, Andersen O. Physical training effects in myasthenia gravis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993 Nov;74(11):1178-80</ref>, concluding "physical training can be carried out safely in mild MG and provides some improvement of muscle force".<br> | One study showed clear benefit from a strength training exercise programme for a group of patients with mild to moderate MG<ref>Lohi EL1, Lindberg C, Andersen O. Physical training effects in myasthenia gravis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993 Nov;74(11):1178-80</ref>, concluding "physical training can be carried out safely in mild MG and provides some improvement of muscle force".<br> | ||

General advice for exercise programmes for people with MG: | General advice for exercise programmes for people with MG: | ||

*Aim to strengthen large muscle groups, particularly proximal muscles of shoulders and hips | *Aim to strengthen large muscle groups, particularly proximal muscles of shoulders and hips | ||

*Advise patient to do the exercises at their "best time of day" ie. when not feeling tired - for the majority of MG patients this will be morning | *Advise patient to do the exercises at their "best time of day" ie. when not feeling tired - for the majority of MG patients this will be morning | ||

*If patient is taking pyridostigmine, exercise at peak dose ie. 1.5 to 2 hours after taking a dose | *If patient is taking pyridostigmine, exercise at peak dose ie. 1.5 to 2 hours after taking a dose | ||

*Moderate intensity of exercise only: patient should not experience worsening of MG symptoms (eg. ptosis or diploplia) during exercise | *Moderate intensity of exercise only: patient should not experience worsening of MG symptoms (eg. ptosis or diploplia) during exercise | ||

*General aerobic exercise is also valuable, helping with respiratory function as well stamina | *General aerobic exercise is also valuable, helping with respiratory function as well stamina | ||

Revision as of 11:04, 14 January 2015

Original Editor - Wendy Walker

Lead Editors

Historical Aspect[edit | edit source]

The first reported case of MG is likely to be that of the Native American Chief Opechancanough, who died in 1664. It was described by historical chroniclers from Virginia as “the excessive fatigue he encountered wrecked his constitution; his flesh became macerated; the sinews lost their tone and elasticity; and his eyelids were so heavy that he could not see unless they were lifted up by his attendants… he was unable to walk; but his spirit rising above the ruins of his body directed from the litter on which he was carried by his Indians”. In 1672, the English physician Willis first described a patient with “fatigable weakness” involving ocular and bulbar muscles described by his peers as “spurious palsy.” In 1877, Wilks (Guy’s Hospital, London) described the case of a young girl after pathological examination as “bulbar paralysis, fatal, no disease found". In 1879, Wilhelm Erb (Heidelberg, Germany) described three cases of myasthenia gravis in the first paper dealing entirely with this disease, whilst bringing attention to features of bilateral ptosis, diplopia, dysphagia, facial paresis, and weakness of neck muscles. In 1893, Samuel Goldflam (Warsaw, Poland) described three cases with complete description of myasthenia and also analyzed the varying presentations, severity, and prognosis of his cases. Due to significant contributions of Wilhelm Erb and later of Samuel Goldflam, the disease was briefly known as “Erb’s disease” and later for a brief time, it was called “Erb-Goldflam syndrome”.

In 1895, Jolly, at the Berlin Society meeting, described two cases under the title of “myasthenia gravis pseudo-paralytica”. The first two words of this syndrome gradually got accepted as the formal name of this disorder. He also demonstrated a phenomenon, that later came to be known as “Mary Walker effect” after she herself observed and described the same finding in 1938. This was reported as “if you stimulate one group of muscles to exhaustion, weakness is apparent in muscles that are not stimulated; an evidence of a circulating factor causing neuromuscular weakness”

In 1934, Mary Walker realized that MG symptoms were similar to those of curare poisoning, which was treated with physostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor. She demonstrated that physostigmine promptly improved myasthenic symptoms. In 1937, Blalock reported improvement in myasthenic patients after thymectomy. Following these discoveries, cholinesterase inhibitor therapy and thymectomy became standard and accepted forms of treatment for MG.

In 1959-1960, Nastuk et al. and Simpson independently proposed that MG has autoimmune etiology. In 1973, Patrick and Lindstrom were able to induce experimental autoimmune MG (EAMG) in a rabbit model using muscle-like acetylcholine receptor (AChR) immunization. In the 1970s prednisone and azathioprine were introduced as treatment modalities for MG followed by plasma exchange that was introduced for acute treatment of severe MG, all supporting the autoimmune etiology.

Definition[edit | edit source]

Myasthenia Gravis is a relatively rare anautoimmune neuromuscular disease leading to fluctuating muscle weakness and fatigue. Muscle weakness is caused by circulating antibodies that block acetylcholine receptors at the postsynaptic neuromuscular junction,inhibiting the excitatory effects of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine on nicotinic receptors at neuromuscular junctions.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

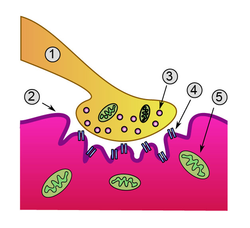

Detailed view of a neuromuscular junction

1. Presynaptic terminal

2. Sarcolemma

3. Synaptic vesicle

4. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

5. Mitochondrion

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

[edit | edit source]

In Myasthenia gravis (MG) antibodies form against nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) postsynaptic receptors at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) of the skeletal muscles[2].The basic pathology is a reduction in the number of ACh receptors (AChRs) at the postsynaptic muscle membrane brought about by an acquired autoimmune reaction producing anti-AChR antibodies[3].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The usual initial complaint is a specific muscle weakness rather than generalized weakness - frequently ocular (eye) symptoms.

Extraocular muscle weakness or ptosis is present initially in 50% of patients, and occurs during the course of illness in 90% of patients.Patients also frequently report diploplia (double vision).

The disease remains exclusively ocular in 10 - 40% of patients.

Rarely, patients have generalized weakness without ocular muscle weakness.

Bulbar muscle weakness is also common, along with weakness of head extension and flexion.

Limb weakness may be more severe proximally than distally.

Isolated limb muscle weakness is the presenting symptom in fewer than 10% of patients.

Weakness is typically least severe in the morning and worsens as the day progresses.

Weakness is increased by exertion and alleviated by rest.

Weakness progresses from mild to more severe over weeks or months, with exacerbations and remissions.

Weakness tends to spread from the ocular to facial to bulbar muscles and then to truncal and limb muscles.

About 87% of patients have generalized disease within 13 months after onset.

Less often, symptoms may remain limited to the extraocular and eyelid muscles for many years.

Classification[edit | edit source]

The most widely utilised classification of MG is the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Clinical Classification[4]

Class I: Any ocular muscle weakness, possible ptosis, no other evidence of muscle weakness elsewhere

Class II: Mild weakness affecting other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity

Class IIa: Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both; may also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles

Class IIb: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles; may also have lesser or equal involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both

Class III: Moderate weakness affecting other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity

Class IIIa: Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both; may also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles

Class IIIb: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles; may also have lesser or equal involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both

Class IV: Severe weakness affecting other than ocular muscles; may also have ocular muscle weakness of any severity

Class IVa: Predominantly affecting limb, axial muscles, or both; may also have lesser involvement of oropharyngeal muscles

Class IVb: Predominantly bulbar and/or respiratory muscles; may also have lesser or equal involvement of limb, axial muscles, or both (Can also include feeding tube without intubation)

Class V: Intubation needed to maintain airway, with or without mechanical ventilation

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to diagnostic tests for the condition

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

add links to outcome measures here (see Outcome Measures Database)

Management / Interventions

[edit | edit source]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation alone or in combination with other forms of treatment can relieve or reduce symptoms for some people with MG.

MG patients should find the optimal balance between physical activity and rest. It is not possible to cure the weakness by active physical training. However, most MG patients are more passive than they need to be. Physical activity and physical training of low to medium intensity is recommended[5].

One study showed clear benefit from a strength training exercise programme for a group of patients with mild to moderate MG[6], concluding "physical training can be carried out safely in mild MG and provides some improvement of muscle force".

General advice for exercise programmes for people with MG:

- Aim to strengthen large muscle groups, particularly proximal muscles of shoulders and hips

- Advise patient to do the exercises at their "best time of day" ie. when not feeling tired - for the majority of MG patients this will be morning

- If patient is taking pyridostigmine, exercise at peak dose ie. 1.5 to 2 hours after taking a dose

- Moderate intensity of exercise only: patient should not experience worsening of MG symptoms (eg. ptosis or diploplia) during exercise

- General aerobic exercise is also valuable, helping with respiratory function as well stamina

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- Basilar Artery Thrombosis

- Brainstem Gliomas

- Cavernous Sinus Syndromes

- Dermatomyositis/Polymyositis

- Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Myocardial Infarction

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Sarcoidosis and Neuropathy

- Thyroid Disease

- Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to key evidence with regards to any of the above headings

Resources

[edit | edit source]

The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) has a comprehensive website

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myasthenia_gravis

- ↑ Strauss AJL, Seigal BC, Hsu KC. Immunofluorescence demonstration of a muscle binding complement fixing serum globulin fraction in Myasthenia Gravis. Proc Soc Exp Biol. 1960;105:184

- ↑ Patric J, Lindstrom JM. Autoimmune response to acetylcholine receptor. Science. 1973;180:871

- ↑ Jaretzki A 3rd, Barohn RJ, Ernstoff RM, et al. Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Neurology. Jul 12 2000;55(1):16-23

- ↑ Skeie GO, Apostolski S, Evoli A et al. Guidelines for treatment of autoimmune neuromuscular transmission disorders. Eur. J. Neurol.17,893–902 (2010)

- ↑ Lohi EL1, Lindberg C, Andersen O. Physical training effects in myasthenia gravis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993 Nov;74(11):1178-80

</div>