Burn Wound Assessment: Difference between revisions

Carin Hunter (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Carin Hunter|Carin Hunter]] based on the course by [https://members.physio-pedia.com/instructor/diane-merwarth// Diane Merwarth]<br>'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | <div class="editorbox"> '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Carin Hunter|Carin Hunter]] based on the course by [https://members.physio-pedia.com/instructor/diane-merwarth// Diane Merwarth]<br>'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | ||

== | == Burn Wound Terminology == | ||

''' | '''Eschar:''' Eschar refers to the nonviable layers of skin or tissue indicating deep partial or full thickness injury. It is black, thick and leathery in appearance. This word is ''not'' synonymous with the word "scab". | ||

'''Scab:''' Dry, crusty residue accumulated on top of a wound, resulting from coagulation of blood, purulent drainage, serum or a combination of all. | '''Scab:''' Dry, crusty residue accumulated on top of a wound, resulting from coagulation of blood, purulent drainage, serum or a combination of all. | ||

'''Pseudo-Eschar:''' A thick gelatinous yellow or tan film that forms with | '''Pseudo-Eschar:''' A thick gelatinous yellow or tan film that forms with silver sulfadiazine cream combining with wound exudate. It can often be mistaken for eschar, but it can be removed with mechanical debridement. | ||

''' | '''Petechiae''': Pinpoint, round spots that appear on the skin as a result of bleeding. The spots can appear red, brown or purple in colour.<gallery> | ||

File:Eschar hand.jpeg|Eschar formation over burn wound on hand | |||

File:Eschar elbow.jpeg|Eschar formation over burn wound on elbow | |||

File:Scab.png|Scab | |||

File:Pseudo-eschar hand.jpeg|Pseudo-eschar formation over burn wound on hand | |||

File:Pseudo-eschar.png|Pseudo-eschar formation over burn wound bed | |||

File:Petechiae hand.png|Petechiae on back of hand | |||

</gallery>''All photos used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT'' | |||

==Classification by Depth== | ==Classification by Depth== | ||

For an overview on wound healing, and the anatomy and physiology of the skin, please read [[Skin Anatomy, Physiology, and Healing Process|this article]]. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|'''Type''' | |'''Type''' | ||

| Line 20: | Line 26: | ||

|'''Prognosis and Complications''' | |'''Prognosis and Complications''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |'''Superficial''' | ||

(formerly first-degree burn) | |||

|Epidermis | |Epidermis | ||

|Red | | | ||

Dry | * Red | ||

* Dry | |||

Pain | * Pain | ||

* No blisters | |||

No blisters | |Re-epithelialisation takes 2-5 days | ||

|Re- | | | ||

|Heals well | * Heals well | ||

Repeated sunburns increase the risk of skin cancer later in life | * Repeated sunburns increase the risk of skin cancer later in life | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |'''Superficial Partial Thickness''' | ||

|Epidermis and | (formerly second-degree burn) | ||

|Redness with a clear blister | |Epidermis and extends into the superficial dermis | ||

Blanches with pressure, but shows rapid capillary refill when released | | | ||

* Redness with a clear blister | |||

Generally moist | * Blanches with pressure, but shows rapid capillary refill when released | ||

* Generally moist | |||

Very painful | * Very painful | ||

* Hair attachments are intact | |||

Hair attachments are intact | * Wound bed pink to red | ||

|Re-epithelialisation takes 1-2 weeks | |||

Wound bed pink to red | | | ||

|Re- | * Low risk of infection unless patient is compromised | ||

|Low risk of infection unless patient is compromised | * No scarring typically | ||

No scarring typically | * Oedema is common | ||

Oedema is common | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |'''Deep Partial Thickness''' | ||

(formerly deep second-degree burn) | |||

|Extends into deep (reticular) dermis | |Extends into deep (reticular) dermis | ||

| | |||

* Appears yellow or white. | |||

Less blanching than superficial. Sluggish capillary refill indicates vascular damage | * Less blanching than superficial. Sluggish capillary refill indicates vascular damage | ||

* Hair attachments are intact | |||

Hair attachments are intact | * Pain is often absent at this depth but is variable | ||

* Blisters are uncommon | |||

* Often moist and waxy | |||

* Wound bed shades of red, yellow, white | |||

Blisters are uncommon | |Re-epithelialisation takes 2-5 weeks. | ||

Often moist and waxy | |||

Wound bed shades of red, yellow, white | |||

|Re- | |||

Some require surgical closure | Some require surgical closure | ||

|Scarring, contractures (may require excision and skin grafting) | | | ||

Oedema | * Scarring, contractures (may require excision and skin grafting) | ||

* Oedema | |||

Circumferential burns at risk for compartment syndrome | * Circumferential burns at risk for compartment syndrome | ||

* Increased risk of infection due to depth and impaired blood flow | |||

Increased risk of infection due to depth and impaired blood flow | |- | ||

|'''Full Thickness''' | |||

(formerly third-degree burn) | |||

|Extends through entire dermis and into the hypodermis | |||

| | |||

* Shades of brown, tan, waxy white, cherry red, sometimes with petechiae | |||

* Appearance can vary from waxy white, leathery grey or charred black. | |||

* Skin is dry, lacking in elasticity | |||

* No blanching | |||

* Not painful (nerve ending damage is common) | |||

* Stiff and white/brown | |||

* Initially painfree | |||

* Hair attachments absent | |||

* No blanch response indicates capillary destruction | |||

|Prolonged (months) and usually requires surgical interventions to ultimately close | |||

| | |||

* Increased risk of infection due to capillary destruction | |||

* Eschar, or the dead, denatured skin, is removed | |||

* Results in scarring and contractures | |||

|- | |- | ||

|''' | |'''Subcutaneous''' | ||

| | (formerly fourth-degree burn) | ||

| | |Destruction of dermis and hypodermis, and into underlying fat, muscle and bone | ||

| | |||

* Charred with eschar | |||

* Dry | |||

* No elasticity | |||

* Initially painfree | |||

* Hair attachments absent | |||

* No blanch response indicates capillary destruction | |||

|Does not heal on its own | |||

Requires surgery and reconstruction | |||

| | |||

* Amputation | |||

* Significant functional impairment | |||

* Death | |||

|} | |||

<gallery> | |||

File:Superficial burn.png|Superficial burn wound | |||

File:Superficial partial burn hand 2.jpeg|Superficial partial burn wound | |||

File:Superficial partial burn thigh.jpeg|Superficial partial burn wound | |||

File:Superficial partial burn hand.jpeg|Superficial partial burn wound | |||

File:Deep Partial Burn elbow.jpeg|Deep partial burn wound | |||

File:Deep partial burn scalp.jpeg|Deep partial burn wound | |||

File:Deep partial burn scars.jpeg|Resulting scars of a deep partial burn wound | |||

File:Full thickness burn hand and wrist.jpeg|Full thickness burn wound | |||

File:Full thickness burn forearm.png|Full thickness burn wound | |||

File:Full thickness burn chest.jpeg|Full thickness burn wound | |||

File:Full thickness burn scar.jpeg|Resulting scars of a full thickness burn wound | |||

File:Subcutaneous burn tendon.jpeg|Subcutaneous burn wound with exposed tendon | |||

File:Subcutaneous burn leg.jpeg|Subcutaneous burn wound | |||

File:Subcutaneous burn hand.jpeg|Subcutaneous burn wound | |||

</gallery>''All photos used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT'' | |||

=== Circumferential burn injury special considerations === | |||

A circumferential burn wound is typically found around an extremity or the torso and puts the patient at a significant risk for compartment syndrome. This pattern of burn injury involves deep partial thickness, full thickness, and or subcutaneous burns. | |||

'''Circumferential burn injury signs and symptoms for potential compartment syndrome:''' | |||

* Out of proportion pain with any movement distal to the circumferential injury. | |||

* Diminished or lack of a pulse distal to the area of circumferential injury. | |||

* Diminished or lack of capillary refill in the fingers and the toes. However, assessment for compartment syndrome can be limited if the injury prevents assessment of capillary refill due to extremity damage or amputation. | |||

* A red flag sign of developing compartment syndrome is a decrease in temperature of the tissue distal to the area of circumferential injury, especially on an extremity. | |||

* For patients with circumferential burn injuries around the torso: high concern for development of compartment syndrome if they experience difficulty breathing or an increase in difficulty breathing. | |||

<div class="row"> | |||

<div class="col-md-6">[[File:Circumferential burn 1.jpeg|thumb|''Used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT'']]</div> | |||

<div class="col-md-6"> [[File:Circumferential burn 2.jpeg|none|thumb|''Used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT'']]</div> | |||

</div> | |||

If a patient is experiencing the signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome, the medical team should be immediately alerted for further assessment and intervention. A bedside or surgical escharotomy will be needed to relieve the resulting pressures of compartment syndrome. | |||

== Blanch Test == | |||

The blanch test is similar to the [[Capillary Refill Test|capillary refill test]]. It is a bedside exam to assess blood flow to the capillaries of the skin. This can be performed over intact skin or in a wound bed itself. | |||

| | |||

'''To perform the test:''' | |||

# Gently but firmly compress the tissue to be tested until it turns white. | |||

# Record the time taken for the area to return to the previous colour. | |||

# Refill time should take 3 seconds or less. If the refill time is longer, suspect capillary damage. If there is no change in colour with applied pressure, suspect capillary destruction. | |||

The following optional video includes a demonstration of the blanch test.{{#ev:youtube|THjmjtDDDoc}} | |||

| | |||

== Jackson's Burn Wound Model == | |||

Jackson's Burn Wound Model<ref>Harish V, Li Z, Maitz PK. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305417918308726 First aid is associated with improved outcomes in large body surface area burns.] Burns. 2019 Dec 1;45(8):1743-8.</ref> is a model used to understand the pathophysiology of a burn would. This model divides the wound into three zones. | |||

*'''<u>Zone of Coagulation:</u>''' (outlined in purple below) This is the central area of the injury and has experienced the greatest amount of tissue damage. It is often characterised by complete destruction of the capillaries leading to cell death. This is irreversible as there is no capillary refill. | |||

*'''<u>Zone of Stasis or Zone of Ischaemia:</u>''' (outlined in green below) This area is adjacent to the zone of coagulation and as the name suggests, it is a zone in which the there is slowing of circulating blood due to the damage. These are areas of deep partial thickness burns, or burns of indeterminate depth. This zone can usually be saved with the correct wound care. Capillaries are often compromised by oedema due to hypovolemia and/or vasoconstrictive mediators responding to injury. It is reversible if capillary flow can be restored. | |||

*'''<u>Zone of Hyperaemia:</u>''' (outlined in blue below) This zone is located around the edge of the previous zone and is characterised by superficial and superficial partial thickness burns and has a robust capillary refill. This is an area of increased circulation due to vasodilators, such as histamine, that are released in response to the burn injury. This tissue has a good recovery rate, as long as there are no complications such as severe sepsis or prolonged hypo-perfusion. This area will completely recover without intervention unless complications occur. | |||

= | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-6">[[File:Jackson's 1.jpeg|thumb|Zone of coagulation outlined in purple; zone of stasis in green; zone of hyperaemia in blue|alt=|none]]</div> | |||

<div class="col-md-6">[[File:Jackson's 2.jpeg|thumb|Zone of coagulation outlined in purple; zone of stasis in green; zone of hyperaemia in blue|alt=|none]] </div> | |||

</div> | |||

==== Burn Wound Conversion ==== | ==== Burn Wound Conversion ==== | ||

'''Burn Wound Conversion:''' <ref>Palackic A, Jay JW, Duggan RP, Branski LK, Wolf SE, Ansari N, El Ayadi A. [https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/58/7/922 Therapeutic Strategies to Reduce Burn Wound Conversion.] Medicina. 2022 Jul;58(7):922.</ref> This refers to the worsening of tissue damage in a | '''Burn Wound Conversion:'''<ref>Palackic A, Jay JW, Duggan RP, Branski LK, Wolf SE, Ansari N, El Ayadi A. [https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/58/7/922 Therapeutic Strategies to Reduce Burn Wound Conversion.] Medicina. 2022 Jul;58(7):922.</ref> True burn wound conversion is a deterioration of the wound due to events unrelated to the initial burn injury. This refers to the worsening of tissue damage in a burn wound which previously was expected to spontaneously heal, but instead it increases in depth to a deeper wound which may require surgical intervention. | ||

'''Potential Causes:''' | '''Potential Causes:''' | ||

| Line 137: | Line 179: | ||

* Infection | * Infection | ||

* Oedema | * Oedema | ||

<gallery> | |||

File:Desiccation 1.jpeg|Example of wound prior to desiccation | |||

File:Desiccation 2.jpeg|Example of wound after desiccation | |||

File:Infection 1.jpeg|Example of wound prior to infection | |||

File:Infection 2.jpeg|Example of wound after infection has set in | |||

File:Edema hand.jpeg|Example of wound oedema in hand and fingers | |||

</gallery>''All photos used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT'' | |||

== Total Body Surface Area == | == Total Body Surface Area == | ||

Total body surface area is an important figure when applying the Parkland Burn Formula. This formula is the most widely used formula to estimate the fluid resuscitation required by a patient with a burn wound upon on hospital admission. It is usually determined within the first 24 hours of admission. | |||

The latest research | When applying this formula, the first step is to calculate the percentage of body surface area (BSA) damaged. This is most commonly calculated using the "Wallace Rule of Nines".<ref>Bereda G. [http://cmhrj.com/index.php/cmhrj/article/view/47 Burn Classifications with Its Treatment and Parkland Formula Fluid Resuscitation for Burn Management: Perspectives.] Clinical Medicine And Health Research Journal. 2022 May 12;2(3):136-41.</ref> When conducting a paediatric assessment, the Lund-Browder Method is commonly used, as children have a greater percentage surface area of their head and neck compared to an adult. The formula recommends 4 millilitres per kilogram of body weight in adults (3 millilitres per kilogram in children) per percentage burn of total body surface area (%TBSA) of crystalloid solution over the first 24 hours of care.<ref>Mehta M, Tudor GJ. [https://europepmc.org/article/NBK/nbk537190 Parkland formula]. 2019</ref><blockquote>4 mL/kg/%TBSA (3 mL/kg/%TBSA in children) = total amount of crystalloid fluid during first 24 hours</blockquote>The latest research indicates that while this method is still in use, the fluid levels should be constantly monitored, while assessing the urine output,<ref>Ahmed FE, Sayed AG, Gad AM, Saleh DM, Elbadawy AM. [https://journals.ekb.eg/article_237338_719deabff050284526195f63d0c8ffae.pdf A Model for Validation of Parkland Formula for Resuscitation of Major Burn in Pediatrics.] The Egyptian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2022 Apr 1;46(2):155-8.</ref> to prevent over-resuscitation or under-resuscitation.<ref>Ete G, Chaturvedi G, Barreto E, Paul M K. [https://medcentral.net/doi/full/10.1016/j.cjtee.2019.01.006 Effectiveness of Parkland formula in the estimation of resuscitation fluid volume in adult thermal burns.] Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2019 Apr 1;22(02):113-6.</ref> | ||

==== Calculation of Percentage Burn of Total Body Surface Area ==== | ==== Calculation of Percentage Burn of Total Body Surface Area ==== | ||

| Line 182: | Line 229: | ||

=====3. Palmar Surface Method===== | =====3. Palmar Surface Method===== | ||

The "Rule of Palm" or Palmar Surface Method can be used to estimate body surface area of a burn. This rule indicates that the palm | The "Rule of Palm" or Palmar Surface Method can be used to estimate body surface area of a burn. This rule indicates that the patient's palm (with the exclusion of the fingers and wrist) is approximately 1% of the patient's body surface area. When a quick estimate is required, the percentage body surface area will be the number of the patient's own palm it would take to cover their injury. It is important to use the patient's palm and not the provider's palm. | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | [[Category:Course Pages]] | ||

[[Category:Burns]] | [[Category:Burns]] | ||

[[Category:Assessment]] | [[Category:Assessment]] | ||

[[Category:ReLAB-HS Course Page]] | [[Category:ReLAB-HS Course Page]] | ||

Latest revision as of 00:26, 7 June 2023

Top Contributors - Carin Hunter, Stacy Schiurring and Jess Bell

Burn Wound Terminology[edit | edit source]

Eschar: Eschar refers to the nonviable layers of skin or tissue indicating deep partial or full thickness injury. It is black, thick and leathery in appearance. This word is not synonymous with the word "scab".

Scab: Dry, crusty residue accumulated on top of a wound, resulting from coagulation of blood, purulent drainage, serum or a combination of all.

Pseudo-Eschar: A thick gelatinous yellow or tan film that forms with silver sulfadiazine cream combining with wound exudate. It can often be mistaken for eschar, but it can be removed with mechanical debridement.

Petechiae: Pinpoint, round spots that appear on the skin as a result of bleeding. The spots can appear red, brown or purple in colour.

All photos used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT

Classification by Depth[edit | edit source]

For an overview on wound healing, and the anatomy and physiology of the skin, please read this article.

| Type | Layers Involved | Signs and Symptoms | Healing Time | Prognosis and Complications |

| Superficial

(formerly first-degree burn) |

Epidermis |

|

Re-epithelialisation takes 2-5 days |

|

| Superficial Partial Thickness

(formerly second-degree burn) |

Epidermis and extends into the superficial dermis |

|

Re-epithelialisation takes 1-2 weeks |

|

| Deep Partial Thickness

(formerly deep second-degree burn) |

Extends into deep (reticular) dermis |

|

Re-epithelialisation takes 2-5 weeks.

Some require surgical closure |

|

| Full Thickness

(formerly third-degree burn) |

Extends through entire dermis and into the hypodermis |

|

Prolonged (months) and usually requires surgical interventions to ultimately close |

|

| Subcutaneous

(formerly fourth-degree burn) |

Destruction of dermis and hypodermis, and into underlying fat, muscle and bone |

|

Does not heal on its own

Requires surgery and reconstruction |

|

All photos used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT

Circumferential burn injury special considerations[edit | edit source]

A circumferential burn wound is typically found around an extremity or the torso and puts the patient at a significant risk for compartment syndrome. This pattern of burn injury involves deep partial thickness, full thickness, and or subcutaneous burns.

Circumferential burn injury signs and symptoms for potential compartment syndrome:

- Out of proportion pain with any movement distal to the circumferential injury.

- Diminished or lack of a pulse distal to the area of circumferential injury.

- Diminished or lack of capillary refill in the fingers and the toes. However, assessment for compartment syndrome can be limited if the injury prevents assessment of capillary refill due to extremity damage or amputation.

- A red flag sign of developing compartment syndrome is a decrease in temperature of the tissue distal to the area of circumferential injury, especially on an extremity.

- For patients with circumferential burn injuries around the torso: high concern for development of compartment syndrome if they experience difficulty breathing or an increase in difficulty breathing.

If a patient is experiencing the signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome, the medical team should be immediately alerted for further assessment and intervention. A bedside or surgical escharotomy will be needed to relieve the resulting pressures of compartment syndrome.

Blanch Test[edit | edit source]

The blanch test is similar to the capillary refill test. It is a bedside exam to assess blood flow to the capillaries of the skin. This can be performed over intact skin or in a wound bed itself.

To perform the test:

- Gently but firmly compress the tissue to be tested until it turns white.

- Record the time taken for the area to return to the previous colour.

- Refill time should take 3 seconds or less. If the refill time is longer, suspect capillary damage. If there is no change in colour with applied pressure, suspect capillary destruction.

The following optional video includes a demonstration of the blanch test.

Jackson's Burn Wound Model[edit | edit source]

Jackson's Burn Wound Model[1] is a model used to understand the pathophysiology of a burn would. This model divides the wound into three zones.

- Zone of Coagulation: (outlined in purple below) This is the central area of the injury and has experienced the greatest amount of tissue damage. It is often characterised by complete destruction of the capillaries leading to cell death. This is irreversible as there is no capillary refill.

- Zone of Stasis or Zone of Ischaemia: (outlined in green below) This area is adjacent to the zone of coagulation and as the name suggests, it is a zone in which the there is slowing of circulating blood due to the damage. These are areas of deep partial thickness burns, or burns of indeterminate depth. This zone can usually be saved with the correct wound care. Capillaries are often compromised by oedema due to hypovolemia and/or vasoconstrictive mediators responding to injury. It is reversible if capillary flow can be restored.

- Zone of Hyperaemia: (outlined in blue below) This zone is located around the edge of the previous zone and is characterised by superficial and superficial partial thickness burns and has a robust capillary refill. This is an area of increased circulation due to vasodilators, such as histamine, that are released in response to the burn injury. This tissue has a good recovery rate, as long as there are no complications such as severe sepsis or prolonged hypo-perfusion. This area will completely recover without intervention unless complications occur.

Burn Wound Conversion[edit | edit source]

Burn Wound Conversion:[2] True burn wound conversion is a deterioration of the wound due to events unrelated to the initial burn injury. This refers to the worsening of tissue damage in a burn wound which previously was expected to spontaneously heal, but instead it increases in depth to a deeper wound which may require surgical intervention.

Potential Causes:

- Dessication

- Infection

- Oedema

All photos used with kind permission from Diane Merwarth, PT

Total Body Surface Area[edit | edit source]

Total body surface area is an important figure when applying the Parkland Burn Formula. This formula is the most widely used formula to estimate the fluid resuscitation required by a patient with a burn wound upon on hospital admission. It is usually determined within the first 24 hours of admission.

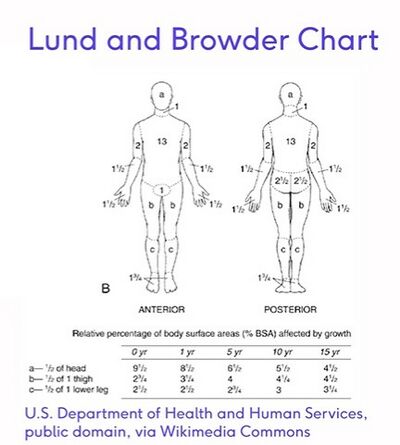

When applying this formula, the first step is to calculate the percentage of body surface area (BSA) damaged. This is most commonly calculated using the "Wallace Rule of Nines".[3] When conducting a paediatric assessment, the Lund-Browder Method is commonly used, as children have a greater percentage surface area of their head and neck compared to an adult. The formula recommends 4 millilitres per kilogram of body weight in adults (3 millilitres per kilogram in children) per percentage burn of total body surface area (%TBSA) of crystalloid solution over the first 24 hours of care.[4]

4 mL/kg/%TBSA (3 mL/kg/%TBSA in children) = total amount of crystalloid fluid during first 24 hours

The latest research indicates that while this method is still in use, the fluid levels should be constantly monitored, while assessing the urine output,[5] to prevent over-resuscitation or under-resuscitation.[6]

Calculation of Percentage Burn of Total Body Surface Area[edit | edit source]

- The Rule of Nine

- Lund-Browder Method

- Palmer Method

1. The Rule of Nine[edit | edit source]

| Body Part | Percentage for Rule of Nine |

| Head and Neck | 9% |

| Entire chest | 9% |

| Entire abdomen | 9% |

| Entire back | 18% |

| Lower Extremity | 18% each |

| Upper Extremity | 9% each |

| Groin | 1% |

2. Lund-Browder Method[edit | edit source]

3. Palmar Surface Method[edit | edit source]

The "Rule of Palm" or Palmar Surface Method can be used to estimate body surface area of a burn. This rule indicates that the patient's palm (with the exclusion of the fingers and wrist) is approximately 1% of the patient's body surface area. When a quick estimate is required, the percentage body surface area will be the number of the patient's own palm it would take to cover their injury. It is important to use the patient's palm and not the provider's palm.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Harish V, Li Z, Maitz PK. First aid is associated with improved outcomes in large body surface area burns. Burns. 2019 Dec 1;45(8):1743-8.

- ↑ Palackic A, Jay JW, Duggan RP, Branski LK, Wolf SE, Ansari N, El Ayadi A. Therapeutic Strategies to Reduce Burn Wound Conversion. Medicina. 2022 Jul;58(7):922.

- ↑ Bereda G. Burn Classifications with Its Treatment and Parkland Formula Fluid Resuscitation for Burn Management: Perspectives. Clinical Medicine And Health Research Journal. 2022 May 12;2(3):136-41.

- ↑ Mehta M, Tudor GJ. Parkland formula. 2019

- ↑ Ahmed FE, Sayed AG, Gad AM, Saleh DM, Elbadawy AM. A Model for Validation of Parkland Formula for Resuscitation of Major Burn in Pediatrics. The Egyptian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2022 Apr 1;46(2):155-8.

- ↑ Ete G, Chaturvedi G, Barreto E, Paul M K. Effectiveness of Parkland formula in the estimation of resuscitation fluid volume in adult thermal burns. Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2019 Apr 1;22(02):113-6.