Core stabilisation exercises vs decompression surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Lyle Brennan (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

The 3 studies included that focused on core stability exercises are as follows: | The 3 studies included that focused on core stability exercises are as follows: | ||

[[File: | [[File:Imagedf.png|center|results]] | ||

What can be concluded from the overall study is that core exercises offer a low-cost clinically and statistical effective intervention for patients with stenosis who present with pain and reduced disability. | What can be concluded from the overall study is that core exercises offer a low-cost clinically and statistical effective intervention for patients with stenosis who present with pain and reduced disability. | ||

Revision as of 11:21, 18 May 2023

1. Lumbar stenosis/Introduction- Link to Physiopedia page on Lumbar stenosis[edit | edit source]

Role: Malachi

- Definition

- Severities

- Affects on patients and health service

- Symptoms

- Epidemiology/Aetiology

- Diagnosis

- Relationship to LBP and reduced ADLS?

2. Current practice[edit | edit source]

Role:Toby

- Guidelines

- Gold standard

- Indications for surgery

Core stabilisation exercise[edit | edit source]

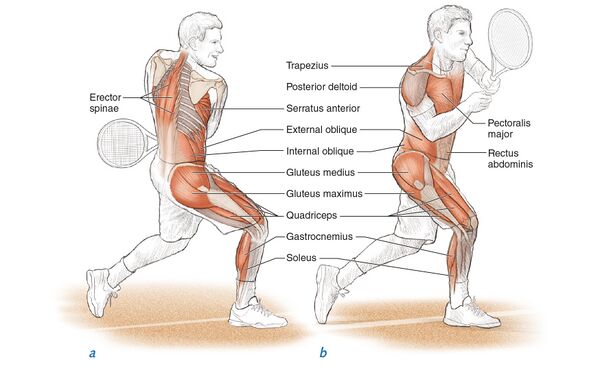

When talking about core stability, this is referencing multiple groups of muscles that surrounding the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex. These muscles play a vital role in everyday life by: (Kibler, Press and Sciascia, 2006)

- Allowing bodies to remain stable by controlling the position and motion of the trunk over the pelvis

- Offload excessive loads from the spine

- Allows for the control of force transfer and motion along the kinetic chain

- Prevent injury

Main inner core muscles:

- Pelvic floor

- Transversus abdominis

- Internal abdominals obliques

- Multifidus

Main outer core muscles:

- Rectus abdominus

- External obliques

- Quadratus lumborum

- Glutes

These above muscles produce high torque to counterbalance external forces impacting the spine; thus, this group of muscles is secondarily responsible for maintaining spinal stability, aiding in improving function and reducing pain (Chang, Lin and Lai, 2015)

What's the aim?[edit | edit source]

When treating patients with stenosis it’s important to keep in mind exercises does not directly alter the stenotic changes. The idea is that these exercises increase the support on the spinal column (Matsuwaka and Liem, 2018). Supporting the previous point, Goren et al., 2010 found positive effect on pain relief, muscle power, motor skill and improved daily activity from core stabilisation exercises.

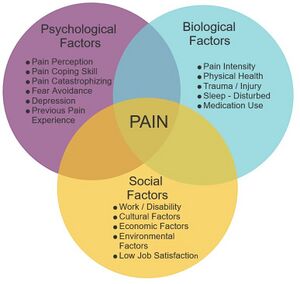

Exercise in general for patients with lumbar pathologies gain much more than physiological benefits. Sculco et al., 2001 found also has a clinically beneficial significant improvements on psychosocial barriers such as anger, fear or confusion which prevent activities of daily living for patients with spinal stenosis (Sculco et al., 2001)

Do core exercises improve outcomes in stenosis?[edit | edit source]

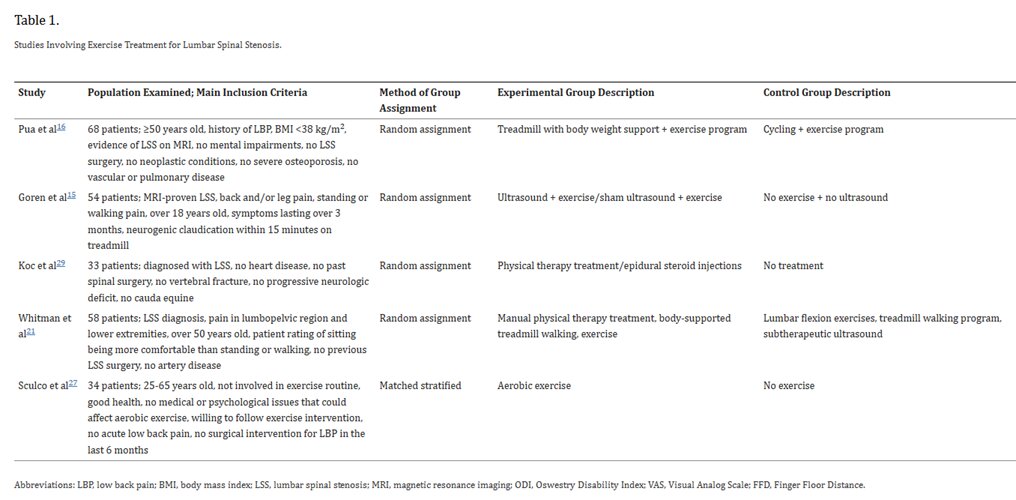

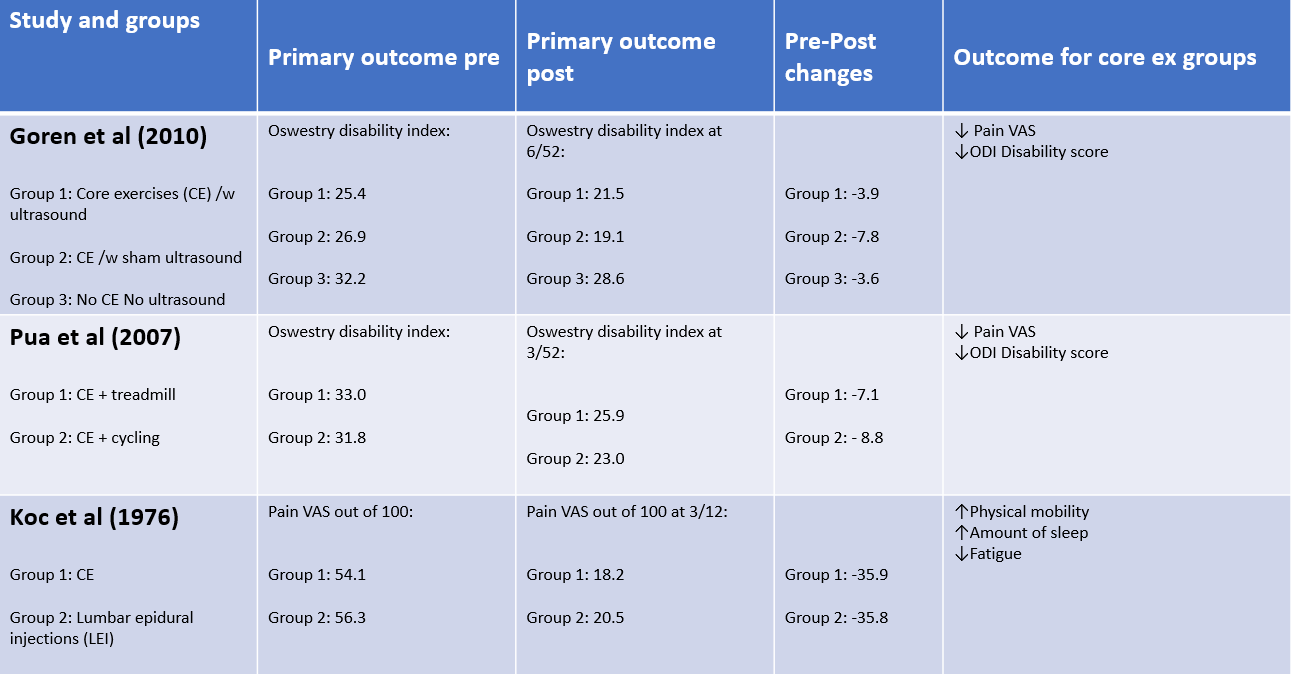

A SR review by (Slater et al., 2015) looks into perceived influence of exercise on pain and disability in patients with lumbar stenosis. This study includes 5 of 310 RCTS including 238 patients with lumbar stenosis and similar demographics. Methodological quality of all studies was assessed with PEDro averaging 6.2/10 with a range of 2-8 with only 1 study not having blinded subjects.

The 3 studies included that focused on core stability exercises are as follows:

What can be concluded from the overall study is that core exercises offer a low-cost clinically and statistical effective intervention for patients with stenosis who present with pain and reduced disability.

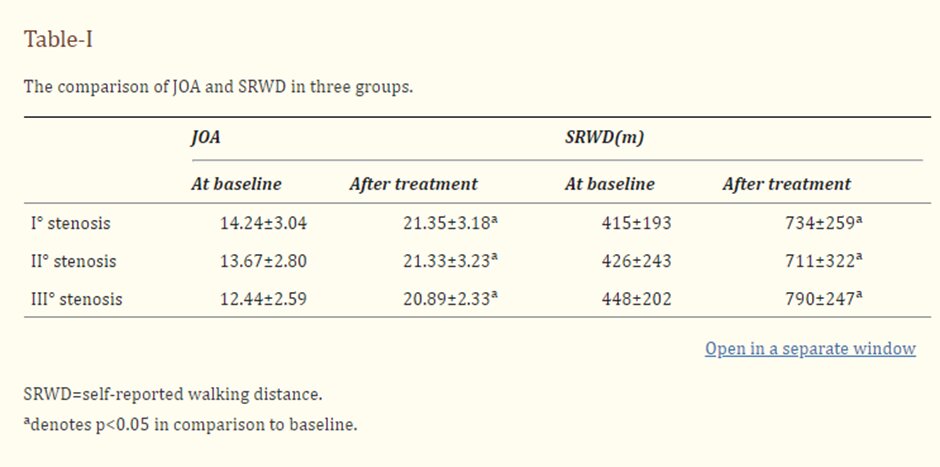

Does stenosis severity impact the effectiveness of core exercise?[edit | edit source]

This question is explored by Chen et al., 2017, looking if core exercise effectiveness correlates with the severity of spinal stenosis.

This study included:

- 42 participants

- 3 groups - varying degree of spinal stenosis

- daily core stability exercises over 6 weeks

Outcomes:

- Japanese Orthopaedic association score (JAO)

- Self-reported walking capacity.

The outcome of the results of this study were able to confirm that the severity of stenosis diameter does not have any correlation to the effectiveness of core exercises when looking at disability and walking distance improvements. Understanding this allows us to vastly increase the scope of appropriate patients. It is however important to note that the severity of stenosis was determined by physiological factors alone without inclusion of psychosocial elements. Further study would be required to include severity of this demographic to further increase ecological validity of the trial.

What core stability exercises are used?[edit | edit source]

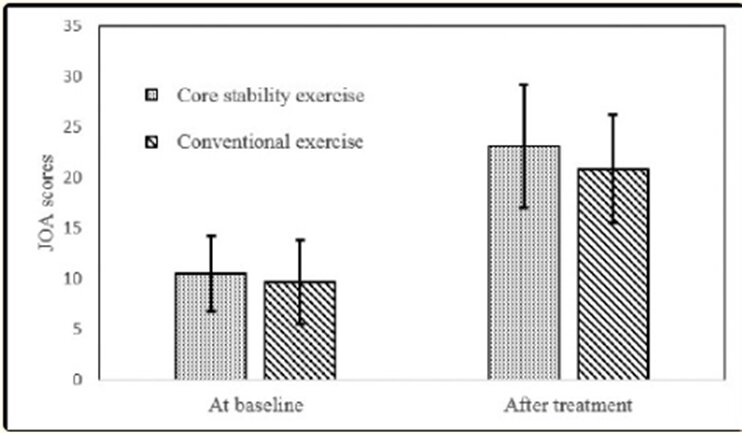

It is unfortunately common for studies to not publish in depth information of the exact exercise programmes they utilise in their studies. Due to this lack of information, there is no one consensus about which are the best set of exercises to use for patients with lumbar stenosis. Mu et al., 2018 published what exercises he used when comparing core exercises to conventional exercise in stenotic patients in an RCT containing 33 participants. Mu found that plank, side plank, bridge, and modified push-up all found to provide higher functional than the conventional group.

See https://www.physio-pedia.com/Core_Stability and https://www.physio-pedia.com/Core_Strengthening for a list of viable exercises and prescription methods.

4. Lumbar decompression surgery[edit | edit source]

Definition[edit | edit source]

Lumbar decompression surgery is a surgery to treat spinal stenosis by removing the tissues that compress the nerve to restore the space in the spinal canal and alleviate pain and improve function. It is an outpatients procedure performed by a neurosurgeon or an orthopaedic surgeon with experience in spinal surgery under general anaesthetic usually as an open surgery and takes over an hour to perform. The aim of the surgery is to create space around the compressed nerve which can be achieved by either laminectomy, discectomy, spinal fusion or a combination of these depending on the structure causing the compression.

Theory of lumbar decompression[edit | edit source]

The aim of the lumbar decompression surgery is to remove the structures causing pressure on the spinal cord and create space around the compressed nerve. Compression can be caused by a disc herniation, spondylosis, spondylolisthesis, arthritis, hypertrophied ligaments or tumour. By removing the compression the irritated nerve can recover.

Depending on the structure causing the compression, one or more procedures can be used:

- Laminectomy – a part of the lamina is removed

- Discectomy – a part of the disc is removed

- Spinal fusion – 2 or more vertebrae are fused together to prevent excessive movement

Criteria for surgery[edit | edit source]

Spinal stenosis is at first managed conservatively. Conservative management includes pain medication, physiotherapy and spinal injections. Surgery may be an options for those that struggle with ADLs or their quality of life is affected and it may be considered for those experiencing serious side effects of medication. It may be considered after around 4 months of failed conservative management. Patients would have to be healthy for surgery to be considered.

Risks of lumbar decompression surgery[edit | edit source]

Just like with any other surgery, there are potential complications including

- Infection

- Blood clot/DVT/pulmonary embolism

- Pain

- Bleeding

- Scarring

- Difficulty passing urine

- Chest infection

Complications of a lumbar decompression surgery includes

- Facial sores and loss of vision

- No relief of the symptoms – continued pain and numbness

- Symptoms return within a few years of the surgery

- Dural tear

- Leakage of cerebrospinal fluid

- Bleeding in the spinal column

- Damage to the spinal nerves or cord/nerve damage

- Loss of bladder or bowel control

- Paralysis

- Death

Risk factors include smoking and obesity. If a repeat surgery is needed, there is a higher risk of complications.

Evidence for efficacy of lumbar decompression surgery[edit | edit source]

The leg pain should improve immediately after surgery. Most patients are discharged after 1-4 days and it takes around 4-6 weeks to reach the expected level of mobility and function. Physiotherapy is completed after the operation to regain strength and movement. Most patients return to work in 4-8 weeks.

A Cochrane review (2016) including 24 RCTs amongst 2352 patients found that those who had decompression plus fusion didn’t have a better outcome than those who only had decompression surgery. There were no differences between different forms of decompression.

A study by Srinivas et al. (2019) looked at the improvement in lower back pain after lumbar decompression for spinal stenosis. 1221 patients were included in the analysis. Lower back pain significantly improved at 3 months and the improvements were sustained at 24 months. Those who didn’t use narcotics, had compensation claims or had an increased severity of lower back pain before surgery achieved better outcomes.

In a review by Sunderland et al. (2021) lumbar decompression surgery was found to be effective at improving quality of life. It was effective at improving leg pain and to a lesser extend back pain at 3 months which was sustained at the 2 year follow up.

A study by Anjarwalla, Brown and McGregor (2007) looked at the outcome of spinal decompression surgery for lumbar stenosis. 51 participants completed the 5 year follow up and significant improvement was noted in back and leg pain and physical function at 6 weeks, 1 year and 5 years, however some deterioration in pain levels were noted at 5 years but still a significant improvement on baseline levels and initially in social function, however those improvements diminished at the 5 year follow up.

5. Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Role: Jack

- SR's looking at short and long term outcomes of core ex vs stenotic decomp

- Develop conclusion on core stability ex vs surgical decomp

- Bring together what has been said overall

References[edit | edit source]

Chang, W.-D., Lin, H.-Y. and Lai, P.-T. (2015). Core strength training for patients with chronic low back pain. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, [online] 27(3), pp.619–622. doi:https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.27.619.

Goren, A., Yildiz, N., Topuz, O., Findikoglu, G. and Ardic, F. (2010). Efficacy of exercise and ultrasound in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, [online] 24(7), pp.623–631. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215510367539.

Kibler, W.B., Press, J. and Sciascia, A. (2006). The Role of Core Stability in Athletic Function. Sports Medicine, [online] 36(3), pp.189–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200636030-00001.

Matsuwaka, S. and Liem, B. (2018). The Role of Exercise in Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Symptoms. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-018-0171-3.

Mu, W., Shang, Y., Mo, Z. and Tang, S. (2018). Comparison of two types of exercises in the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, [online] 34(4). doi:https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.344.15296.

Sculco, A.D., Paup, D.C., Fernhall, B. and Sculco, M.J. (2001). Effects of aerobic exercise on low back pain patients in treatment. The Spine Journal, [online] 1(2), pp.95–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s1529-9430(01)00026-2.

Slater, J., Kolber, M.J., Schellhase, K.C., Patel, C.K., Rothschild, C.E., Liu, X. and Hanney, W.J. (2015). The Influence of Exercise on Perceived Pain and Disability in Patients With Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, [online] 10(2), pp.136–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827615571510.