Clostridium Difficile Infection CDI: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

[[File:Clostridium difficile CDC.jpeg|thumb|Clostridium difficile]] | |||

Clostridium difficile is a type of bacteria that can cause colitis, a serious inflammation of the colon. Infections from C. diff often start after taking antibiotics. It can sometimes be life-threatening<ref name=":0">Web md Clostridium difficile Available:https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/clostridium-difficile-colitis (accessed 12.5.2022)</ref>. | Clostridium difficile is a type of bacteria that can cause colitis, a serious inflammation of the colon. Infections from C. diff often start after taking antibiotics. It can sometimes be life-threatening<ref name=":0">Web md Clostridium difficile Available:https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/clostridium-difficile-colitis (accessed 12.5.2022)</ref>. | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

== Risk Factors == | == Risk Factors == | ||

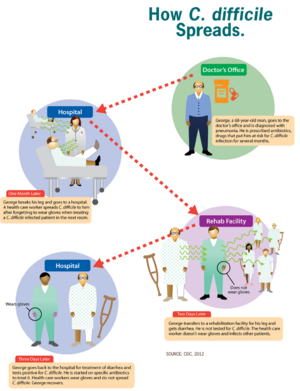

[[File:C. difficile spreads.png|right|frameless]] | |||

C. diff can affect anyone, however cases of C. diff occur when taking antibiotics or not long after finishing taking antibiotics. | C. diff can affect anyone, however cases of C. diff occur when taking antibiotics or not long after finishing taking antibiotics. | ||

| Line 33: | Line 34: | ||

* Loss of appetite | * Loss of appetite | ||

* Nausea<ref name=":1" /> <br> | * Nausea<ref name=":1" /> <br> | ||

== Medications == | == Medications == | ||

| Line 53: | Line 50: | ||

If a serious problems with the colon is suspected, an X-rays or a CT scan of the intestines may be ordered. In rare cases, the doctor may examine the colon with procedures such as a flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy<ref name=":0" />. | If a serious problems with the colon is suspected, an X-rays or a CT scan of the intestines may be ordered. In rare cases, the doctor may examine the colon with procedures such as a flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy<ref name=":0" />. | ||

== Etiology | == Etiology == | ||

C. Difficile bacteria colonize the large colon after exposure. Colonization in areas other than the large colon is quite rare in the human body. The natural anaerobic environment and absence of competing gut flora (due to antibiotic treatment) make the large colon an ideal environment for the bacteria to flourish.For the bacteria to flourish in the gut and damage the host several events must occur so that toxin production is possible. To start, the C. difficile spores must reach an area in the gut where an ample amount of bile salts are present so that they can catalyze the germination of these spores.<ref name="p8">Knetsch C, Lawley T, Hensgens M, Corver J, Wilcox M, Kuijper E. Current application and future perspectives of molecular typing methods to study Clostridium difficile infections. Euro Surveillance: Bulletin Européen Sur Les Maladies Transmissibles = European Communicable Disease Bulletin [serial online]. January 24, 2013;18(4):20381. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 12, 2014</ref><ref name="p4" /><ref name="p2" /> <br>After germination is complete, the bacteria begins produce toxins, initially focusing on a binary toxin that produces microtubule-cell extensions allowing adherence of the bacteria to the intestinal walls. During colonization and immediately following, C. difficile now in a vegetative form releases TcdA and TcdB. The mechanism of A and B toxin secretion is not fully understood, but the it is known that amion acid availability is critical to toxin expression. Primarily acting on the epithelial cells of the intestines, TcdA causes inflammation, fluid secretion, and necrosis of colon tissue. TcdB is a potent cytoxin that may be responsible for systemic damaged present in patients with fulminant CDI due to its cardiotoxic behavior.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p4" /><ref name="p2" /> | C. Difficile bacteria colonize the large colon after exposure. Colonization in areas other than the large colon is quite rare in the human body. The natural anaerobic environment and absence of competing gut flora (due to antibiotic treatment) make the large colon an ideal environment for the bacteria to flourish.For the bacteria to flourish in the gut and damage the host several events must occur so that toxin production is possible. To start, the C. difficile spores must reach an area in the gut where an ample amount of bile salts are present so that they can catalyze the germination of these spores.<ref name="p8">Knetsch C, Lawley T, Hensgens M, Corver J, Wilcox M, Kuijper E. Current application and future perspectives of molecular typing methods to study Clostridium difficile infections. Euro Surveillance: Bulletin Européen Sur Les Maladies Transmissibles = European Communicable Disease Bulletin [serial online]. January 24, 2013;18(4):20381. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 12, 2014</ref><ref name="p4" /><ref name="p2" /> <br>After germination is complete, the bacteria begins produce toxins, initially focusing on a binary toxin that produces microtubule-cell extensions allowing adherence of the bacteria to the intestinal walls. During colonization and immediately following, C. difficile now in a vegetative form releases TcdA and TcdB. The mechanism of A and B toxin secretion is not fully understood, but the it is known that amion acid availability is critical to toxin expression. Primarily acting on the epithelial cells of the intestines, TcdA causes inflammation, fluid secretion, and necrosis of colon tissue. TcdB is a potent cytoxin that may be responsible for systemic damaged present in patients with fulminant CDI due to its cardiotoxic behavior.<ref name="p8" /><ref name="p4" /><ref name="p2" /> | ||

Revision as of 02:09, 12 May 2022

Original Editors - John Hardy from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - John Hardy, Lucinda hampton, Reem Ramadan, Elaine Lonnemann, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Oyemi Sillo, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya and Nupur Smit Shah

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Clostridium difficile is a type of bacteria that can cause colitis, a serious inflammation of the colon. Infections from C. diff often start after taking antibiotics. It can sometimes be life-threatening[1].

- Clostridium difficile is an anerobic, gram-positive bacillus. This rode shaped bacterium exists in vegetative or spore form and can survive harsh environments and common sterilization techniques. Clostridium difficile is resistant to ultra-violent light, high temperatures, and antibiotics.[2]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) has become a serious medical and epidemiological problem, especially in well developed countries. There has been evident increase in incidence and severity of CDI. Prevention, proper diagnosis and effective treatment are necessary to reduce the risk for the patients, deplete the spreading of infection and diminish the probability of recurrent infection. Antibiotics are the fundamental treatment of CDI[3]

C. Difficile is commonly a nosocomial pathogen found in a hospital or similar healthcare facility. Colonization rate of healthy adults is estimated to be 2% while the prevalence of hospitalized adults can be high as 40%. Nearly a third of all C. Difficile infections are community acquired which suggests a recent increase in non-nosocmial infections. [4][5]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

C. diff can affect anyone, however cases of C. diff occur when taking antibiotics or not long after finishing taking antibiotics.

Other risk factorsinclude :

- Being 65 or older

- Recent stay at a hospital or nursing home

- A weakened immune system, such as people with HIV/AIDS, cancer, or organ transplant patients taking immunosuppressive drugs

- Previous infection with C. diff or known exposure to the germs[6]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Symptoms may develop within a few days after taking antibiotics, and include:

- Severe diarrhea

- Fever

- Stomach tenderness or pain

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea[6]

Medications[edit | edit source]

- Vancomycin (Glycopeptide Antibiotics)

-Metroidazole (Nirtoimidazole Antibiotic)

- Rifamimin (Antimicrobial)

-Probiotics

-Immunosuppressants[7][8]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

For definitive diagnosis a stool sample must be collected. Tests include:

- Enzyme immunoassay

- Polymerase chain reaction

- GDH/EIA

- Cell cytotoxicity assay

If a serious problems with the colon is suspected, an X-rays or a CT scan of the intestines may be ordered. In rare cases, the doctor may examine the colon with procedures such as a flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy[1].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

C. Difficile bacteria colonize the large colon after exposure. Colonization in areas other than the large colon is quite rare in the human body. The natural anaerobic environment and absence of competing gut flora (due to antibiotic treatment) make the large colon an ideal environment for the bacteria to flourish.For the bacteria to flourish in the gut and damage the host several events must occur so that toxin production is possible. To start, the C. difficile spores must reach an area in the gut where an ample amount of bile salts are present so that they can catalyze the germination of these spores.[5][4][2]

After germination is complete, the bacteria begins produce toxins, initially focusing on a binary toxin that produces microtubule-cell extensions allowing adherence of the bacteria to the intestinal walls. During colonization and immediately following, C. difficile now in a vegetative form releases TcdA and TcdB. The mechanism of A and B toxin secretion is not fully understood, but the it is known that amion acid availability is critical to toxin expression. Primarily acting on the epithelial cells of the intestines, TcdA causes inflammation, fluid secretion, and necrosis of colon tissue. TcdB is a potent cytoxin that may be responsible for systemic damaged present in patients with fulminant CDI due to its cardiotoxic behavior.[5][4][2]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

-Dehydration

-Ectrolyte disturbances

-Hypoalbuminemia

-Toxic megacolon

-Bowel perforation

-Rrenal failure

-Sepsis

-Clonic ileus

-Toxic dilatation

-Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

-Death[2]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Medical management of CDI depends on the acuity and severity of the infection as well as whether it is an initial or recurrent infection. It is widely recognized that the most important first step in treatment is to discontinue the inciting antibiotic. Discontinuation of antibiotic treatment historically resulted in resolution of the infection, but due to new hypervirulent strains further intervention is recommended. Fluid and electrolyte replacement is suggested for quicker recovery. The available drugs for treatment of a CDI are Vancomycin and Metronidazole. If Vancomycin is the drug selected for treatment it should be administered either rectally or orally. These are the recommended routes of administration because intravenous Vancomycin has shown to be an ineffective treatment of CDI.[8]

On the other hand, Metronidazole has been shown to deliver similar colonic and intraluminal levels regardless of administration. Some researchers advocate oral administration when possible to avoid potential complications with an intravenous route. Though Metronidazole has been shown to be equally as effective as Vancomycin it has a higher rate of unresponsiveness. If patients do not respond to Metronidazole, Vancomycin is then considered. Vancomycin is more commonly the first treatment especially in severe cases of CDI due its lower rate of unresponsiveness and superior efficacy.[2][8]

Mild to moderate cases of CDI are treated with 25o mg of metronidazole every six hours or 125 mg of vacomycin every 6 hours. Treatment course is typically 10-14 days with resolution of symptoms in more than 90% of cases in less than 10 days. Combined use of these drugs is often used in patients with moderate to severe infection especially if accompanied by ileus and or toxic megacolon. Patients with unresolving ileus can be given increased doses as well as frequency of administration (i.e. 500 mg every 6 hours). In severe cases surgical evaluation for colectomy may be indicated to avoid life-threatening complications. In patients with reoccurrent infection pulse or tapering therapy is combined with vancomycin treatment. A course of Rifamimin is also recommended after previous treatments have failed.[8][7]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

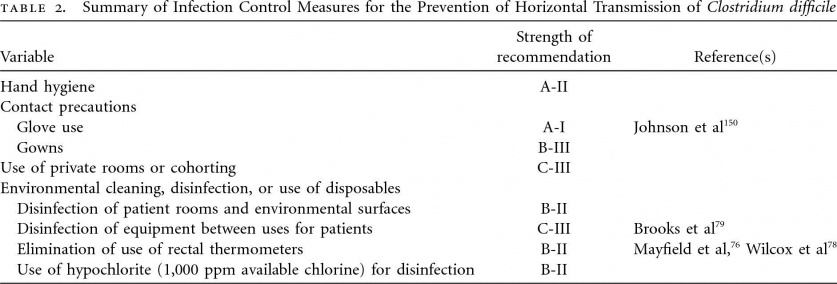

C. difficile infections are primarily managed through pharmaceutical therapy and associated medical treatments. Exercise recommendations for patients with CDI have not been clearly established and are currently based on clinical decision making of the therapeutic team and treating physician. The therapist should take an active role in infection control and prevention measures whenever working with these patients. Infection control measures include: donning gloves and gowns prior to entering patients room, washing hands with soap and water upon departure, treating patients in a private room, educating visitors on proper hygiene measures. Routine environmental screening and use of chlorine-containing cleaning agents is also recommended. Below is a table summarizing the evidence supporting various infection control measures.[4]

Infection Control[4]

Alternative/Holistic Manageme Though patients with CDI have a disturbance in native-gut flora, antimicrobial pharmaceuticals are being investigated as a potential treatment option. There are several antimicrobials under investigation including: tinidazole, rifaximin, rifalazil, nitazoxanide, glycopeptides derivatives, fidoxamicin, and topical bacitracin.[8] Probiotics have also been proposed as a potential treatment option though evidence is not strong enough for it be considered as a primary option. Theoretically probiotics may replenish the native-flora of the colon which was depleted by prolonged anti-biotic treatment. This native flora would then compete with the C. difficile strains for nutrients and habitable space in the colon. Probiotics are reportedly non-pathogenic microorganisms though are not used in immunocompromised patients because of cases of blood-borne infections. The most widely studied probiotics are Saccharomyces and Lactobacillus. Moderate improvements have been demonstrated when probiotics are used in conjunction with vancomycin or metronidazol when compared to the ladder drugs alone. A single case report, demonstrated the effectiveness of reducing the incidence of CDI through concurrent treatment administration of probiotics and antimcobials[9]Another developing treatment strategy is immunotherapy. Inconsistent results have been reported as to whether intravenous administration of human immunoglobulin can neutralize C. difficile toxins A and B in recurrent and sever CDIs. Recent research has reported when given in conjunction with vancomycin, human monoclonal antibodies can significantly reduce the reoccurance rate of CDI. Lastly, research goal of practically every infectious disease is to develop a safe and effective vaccine. Research on a C. difficile vaccine is currently taking place and shown promising results in both animal and human volunteers. Since thorough analysis has not been performed on a large sample of patients its safety and efficacy to date is not establisifferential Diagnosi[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Web md Clostridium difficile Available:https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/clostridium-difficile-colitis (accessed 12.5.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cecil J. Clostridium difficile: Changing Epidemiology, Treatment and Infection Prevention Measures. Current Infectious Disease Reports [serial online]. December 2012;14(6):612-619. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 17, 2014

- ↑ Kukla M, Adrych K, Dobrowolska A, Mach T, Reguła J, Rydzewska G. Guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults. Przeglad gastroenterologiczny. 2020;15(1):1. Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7089862/ (accessed 12.5.2022)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Cohen S, Gerding D, Wilcox M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology [serial online]. May 2010;31(5):431-455. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 12, 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Knetsch C, Lawley T, Hensgens M, Corver J, Wilcox M, Kuijper E. Current application and future perspectives of molecular typing methods to study Clostridium difficile infections. Euro Surveillance: Bulletin Européen Sur Les Maladies Transmissibles = European Communicable Disease Bulletin [serial online]. January 24, 2013;18(4):20381. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 12, 2014

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 CDC C. diff (Clostridioides difficile) Available:https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/what-is.html (accessed 12.5.2022)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 . A. Loshkajian. Pseudomembranous Colitis. Available at: http://www.eurorad.org/eurorad/case.php?id=1368. Accessed March, 17, 2014

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Drekonja D, Butler M, Wilt T, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Clostridium difficile Treatments: A Systematic Review. Annals Of Internal Medicine [serial online]. December 20, 2011;155(12):839-847. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 14, 2014

- ↑ McFarland L. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea and the treatment of Clostridium difficile disease. The American Journal Of Gastroenterology [serial online]. April 2006;101(4):812-822. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 12, 2014