Subjective Assessment of the Equine Patient: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 378: | Line 378: | ||

* This test can be done with the front and hind limbs, and while it is very non-specific, it provides information to how comfortable the horse is with loading a particular quadrant. | * This test can be done with the front and hind limbs, and while it is very non-specific, it provides information to how comfortable the horse is with loading a particular quadrant. | ||

* If a horse is reluctant to load a particular limb, he will hop sideways, or make postural adjustments with the remaining two weight-bearing limbs. There may also be a lag in response from the horse. This narrows down the region of dysfunction to then be assessed in greater detail | * If a horse is reluctant to load a particular limb, he will hop sideways, or make postural adjustments with the remaining two weight-bearing limbs. There may also be a lag in response from the horse. This narrows down the region of dysfunction to then be assessed in greater detail | ||

=== Special Tests === | |||

==== Stork Test ==== | |||

* When one hind limb is lifted, the SIJ on the contralateral hind limb assumes its close-packed position | |||

* To test for potential SIJ pain, the SIJ is loaded unilaterally by lifting the opposite hind leg into slight abduction, thereby increasing the load on the weight-bearing hind limb. After 60 seconds, the horse is immediately trotted away in a straight line | |||

* The test is positive if the horse exhibits an increased lameness of the WEIGHT-BEARING leg, not the flexed leg | |||

* The test should be repeated on the other side to compare | |||

=== Palpation === | |||

When palpating a horse, there are both general and specific features to consider.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

General soft tissue palpation will provide information about:<ref name=":6" /> | |||

* Temperature | |||

* Irritability | |||

* Muscle tone | |||

* Soft tissue thickening or swelling | |||

* The horse's overall reactivity to touch | |||

Specific muscle palpation occurs after the therapist has developed a hypothesis of which muscle/s may be the primary source of symptoms.<ref name=":6" /> You will also palpate bony landmarks. The following table summarises key areas that should be palpated in equine patients.<ref name=":7" /> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

!Cervical Spine | |||

!Fore limb | |||

!Spine | |||

!Hind limb | |||

|- | |||

| | |||

* TMJ | |||

* Occiput | |||

* Wing of Atlas | |||

* Transverse processes of cervical vertebrae | |||

* Insertion of nuchal ligament onto occipital process | |||

* Masseter and temporalis | |||

* Entire length of brachiocephalicas | |||

* Assess symmetry of cervical vertebra along the length of the cervical spine | |||

|Bony landmarks: | |||

* Cranial angle, caudal angle and spine of scapula | |||

* Greater tubercle of the humerus | |||

* Lateral epicondyle of humerus | |||

* Intervertebral spaces of carpus | |||

Important structures: | |||

* Supraspinatus | |||

* Deltoid and its insertion | |||

* Biceps tendon | |||

* Insertion of Pectorals | |||

* Inferior check ligament | |||

* Suspensory, SDFT and DDFT | |||

* Lateral Cartilages | |||

|Bony landmarks: | |||

* Spines of thoracolumbar vertebrae | |||

* Angles of ribs | |||

* Transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae palpable in leaner horses | |||

Important structures | |||

* Supraspinous ligament | |||

* Alignment of spinous processes | |||

* Thoracolumbar fascia | |||

|Bony landmarks: | |||

* Tuber sacrale | |||

* Tuber ischii | |||

* Tuber coxae | |||

* Greater trochanter | |||

* Patella | |||

Important structures: | |||

* Tendons as in front limb | |||

* Sacro-tuberous ligament | |||

|} | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 02:28, 21 April 2021

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Animal physiotherapy is an emerging profession.[1] Physiotherapists who treat human patients are able to use their skills to treat animals. Animal physiotherapists work alongside a multidisciplinary team and usually receive referrals from a veterinarian.[1][2] Physiotherapists complete a functional assessment to identify pain or loss of function caused by pain, injury, disorders or disability. Animal physiotherapists are now part of the team of professionals that equine athletes and their riders now regularly access.

Process of Assessment[edit | edit source]

Equine physiotherapists do not need a pathoanatomic diagnosis to develop management plans for their patients.[2][3] Rather, they approach the assessment from a functional perspective, observing and noting any movement dysfunctions / impairments that may be contributing to a problem, in addition to careful palpation of the horse.[3]

The following skills are considered useful for equine physiotherapists:[3]

- The ability to communicate well with a horse's owner, handler and trainer

- Excellent observation skills (of the horse in motion and at rest)

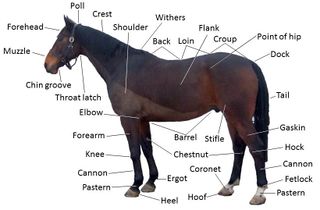

- Good understanding of the anatomy, functional anatomy, and biomechanics of the horse

- Being able to carry out functional movement tests, have effective palpation skills and be able to interpret the findings of their assessment

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

When working with horses, the ability to obtain subjective history is limited - it is very difficult to determine the severity, irritability, nature (SIN) of a condition, its 24- hour pattern and the exact area of pain/ discomfort. Unlike in human physiotherapy, you cannot interview an equine patient, so the animal therapist often has to interview the wider team to find out all the relevant information, including the:[4]

- Rider - what are they feeling during training?

- Coach - what they are seeing during training?

- Owner and Groom - how is the horse at home and has it developed any abnormal behaviours?

- Veterinarian and other medical professionals - what was found on examination and other investigations?

All of this information can help the therapist to develop his / her treatment plan.[4]

- Background information: It is important to have background information (age, gender etc) so that you can identify the horse and contact the MDT for information

- Discipline, training history, the reason for referral: Provides clues about the type of injury, mechanism of injury and cause of injury (i.e. over-training)

- Present medical history: Consider what the problem is and how it has been assessed. What treatment has been given thus far and how has the horse responded?

- Past medical history: This provides clues as to whether or not a previous injury may be causing the horse's current issue. It also indicates what treatments the horse responds to and if the horse has been provided with enough rehabilitation?

- Special questions /red flags: These are similar to those seen in human patients such as a sudden weight loss, general health issues, respiratory conditions ...etc.

These areas will be discussed in further detail below.

1. Age[edit | edit source]

Age gives us clues about potential pathologies and can be considered in a differential diagnosis.[4]

Young Horses (2-6 years)[edit | edit source]

- Developmental problems i.e. osteochondrosis dissecans[5]

- Injuries related to poor motor control to cope with work demands. Still developing soft tissue structures

- Competing racehorses are under huge stress - young thoroughbred horses have been shown to experience a significant number of physiological and anatomical adaptations in response to exercise training[6]

Mid-Aged Horses (7-15 years)[edit | edit source]

- Sport horses are often competing at their peak at this age, so soft tissue injuries due to overuse are more common[4] - ageing and exercise are considered important risk factors for tendon injury[7]

- Biomechanical problems will also cause soft tissue injuries

- Degenerative joint disease (DJD) may already be present in some horses at this age

Older Horses (15-20 years)[edit | edit source]

- Wear and tear is common especially in joints (i.e. DJD / arthritis)

2. Gender[edit | edit source]

Hormonal changes may mimic behavioural changes that are associated with musculoskeletal pain:

- A common behavioural problem can occur in performance mares when these mares exhibit heat or oestrus.[8] Mares begin periods of heat due to increasing day length. In general, these periods of heat last 5 to 7 days out of a 21-day cycle. Clinical signs that affect performance mares include attitude changes, tail swishing, difficulty in training, squealing, horsing, excessive urination, kicking, a decrease in performance, and colic like pain associated with ovulation[9]

- Asking the owner or rider about previous problems with oestrus, or whether there appears to be a regular monthly pattern to the pain or if the mare is experiencing performance-related symptoms can be helpful

3. Length Of Ownership[edit | edit source]

- During the change of ownership of a horse, it is very rare that all the previous medical history is passed on. We are guided by pre-purchase vetting and unfortunately, not all previous musculoskeletal injuries will be obvious during a vetting[4]

- One of the most effective methods we have to identify musculoskeletal pain or discomfort is a horse's behaviour. However, new owners may not know what is ‘normal’ behaviour for their horse yet[4]

4. Discipline and Training History[edit | edit source]

- It is important to understand a horse's training level and what discipline it competes in as these factors will help determine the type of injury / problem, the mechanism and severity of the injury

- Finding out about a horse's last competition will provide the therapist with an understanding of:

- when the horse was (possibly) last put under great strain

- how long the horse has been out of action

- It is important to gain an understanding of a horse's training programme. This will enable the therapist to determine how often the horse is working and what are it is doing. Questions to consider include whether or not the horse is cross-training and if it participates in a range of work / activities (e.g. pole work, jumping, flatwork, hill work or track work and hacking)[4]

5. Present Medical History[edit | edit source]

It is important to find out:[4]

- What the horse's main complaint is

- What behavioural issue has caused the owner to phone an animal therapist (e.g. the horse recently started biting while being tacked up or the horse has stopped wanting to work forward)

- How long the complaint or issue has been present

- If the veterinarian has seen the horse - were there any investigations, is there a diagnosis and has the horse been prescribed any medications and, if so, for how long?

- If there is a 24-hour pattern - does the horse worsen or improve with work? Is the horse worse on walking out the stable in the morning? How long does it take for the horse to improve?

- If there are any other professionals involved in the horses's care - what have they done and how have these interventions helped (other professionals might include: saddle fitter, dentist, chiropractor etc).

6. Past Medical History[edit | edit source]

Information about a horse's medical history may not always available / accurate, but where possible it is important to know:[4]

- What veterinary treatment the horse has had

- Was there a pre-purchase vetting?

- What was picked up on this pre-purchase vetting?

Vetting[11] is the process where a veterinarian is asked to conduct a comprehensive assessment of a horse, including a general health check, a gait assessment, examination of the horse performing strenuous exercise, and a re-assessment 30 minutes post-exercise and finally another trotting assessment.[11] During this process, certain problems may be discovered. X-rays may also be taken during more extensive vettings.[4]

The price of the horse often determines how extensive a vetting is or if there is even a vetting. Some expensive horses or horses who have great potential will be x-rayed every few years as a preventative measure. It is important to note that while these horses may be asymptomatic, the therapist should still attempt to find out if the horse’s veterinarian ever recommended any diagnostic tests that were not actually undertaken.[4]

7. Red Flags[edit | edit source]

Red flags are signs or symptoms that suggest serious pathology may be present.[13]

- The horse's general health should be considered, including if there could be:[4]

- Metabolic diseases such as Cushing’s

- Respiratory diseases such as COPD

- Also consider what medications / supplements the horse may be on. Remember that your subjective assessment should give you an indication of:[4]

- What / where to look for the source of the problem?

- Whether something is not adding up / making sense - this may require a referral

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

The functional assessment should include:[3]

- Active physiological movements

- Palpation and testing of soft tissues

- Passive physiological joint assessment

- Passive accessory joint assessment

Objective physiotherapy tests in the equine assessment are very much based on functional assessment and palpation skills. The assessment consists of four key elements:[4]

Functional Assessment[edit | edit source]

The functional assessment includes an analysis of conformation, gait and a horse's reflexes.

Conformation[edit | edit source]

Proper conformation is believed to be important for a horse's balance, power, manoeuvrability and soundness over the lifespan.[14] It cannot be changed and is usually related to skeletal development. It also includes structural joint alignment.[4] Conformation is considered one of the most reliable predictors of athletic ability and long-term soundness in most horses[14]

NB: Posture, unlike conformation, can be improved. It is dynamic and related to muscle tone and activation.

To assess conformation and posture:[4]

Observe the horse standing on a flat, firm surface.

- First observe the horse’s natural stance – how is the horse most comfortable standing?

- Now try to make the horse stand as square as possible

View the horse from the left, right, front and rear.

- How easy is it for the horse to stand square/ balanced?

- When the horse is made to stand square, can he/she maintain the posture? Is the muscle development symmetrical? Are the feet balanced? What is the limb alignment like?

Back Conformation[edit | edit source]

Typically, a horse's back should be 1/3 of its length (from the highest vertebra of the withers to the point of the hip).[15] Long backed horses are generally more flexible, but they are generally weaker[14] and can be prone to injury as they generally find it harder to work correctly and strengthen their core. Short backed horses are generally strong, but they are more ridged and can be difficult when fitting saddles as they ”run out” of the thoracic spine.

The following table summarises some common leg conformational faults:[4][14]

|

Conformational Faults |

Explanation | Predisposed issues |

|---|---|---|

| Base Wide | Standing with forelimbs outside the plumbline

Distance between the hooves is greater than the distance between centre of thighs; commonly associated with cow-hocks |

Tend to toe out - this results in more weight being distributed to the medial side of the horse's hoof, which can lead to medial stress on joints, medial splint bone stress |

| Base Narrow | Standing with forelimbs inside the plumbline

Distance between the hooves is less than the centre of the thighs, heavily muscled horses (often accompanied by ‘bowlegs’ with hocks too far apart) |

Tend to land on the outside of their hoof wall - can lead to ringbone, lateral sidebone, lateral heel bruises and lateral strain on joints |

| Toed Out | Toes pointing outward | Inward arc when advancing; results in interference with opposite forelimb especially if combined with base- narrow stance. |

| Pigeon Toed | Toes pointing inward | Outward deviation of foot during flight (paddling or winging-out) which interferes with the hind limb |

| Bowlegged | Varus deformity of carpus | Increased tension on the lateral collateral ligament and medial surface of carpal bones |

| Knock-Kneed | Valgus deformity of carpus | Increased stress on medial carpal collateral ligaments, outward rotation of cannon bone, fetlock and foot |

| Camped Out | Entire forelimb from body to ground is too far forward | Causes excessive pressure on the horses's hooves, knee and fetlock joints. This stance might be due to conformational defects, but could also indicate hoof pain (e.g. navicular syndrome, laminitis) |

| Calf Kneed | Backward deviation of carpus | Causes excessive strain on the back ligaments and leg tendons, and pressure on the front of the carpal joint. This means that the horse is more prone to carpal arthrosis, carpal chip fractures, and injuries to the check ligaments |

| Camped Under | Entire limb below elbow placed too far underbody; can occur with a disease as well as be a conformational fault | Overloading of forelimbs, shortened cranial phase of stride and low arc of foot flight can lead to stumbling |

| Buck Kneed | Forward deviation of carpus; knees knuckle forward, so this conformation is dangerous for the rider | Distributes pressure unevenly over the leg, so causes strain on sesamoid bones, suspensory ligament, and SDFT and extensor carpi radialis muscle |

| Sickle Hocked | Excessive angulation of the hock (<53) | High stress on the hock joint and ligaments / tendons. It can result in issues such as curbed hocks, bog spavin (i.e. tarsal hydrarthrosis or tarsocrural effusions[16]) and bone spavins (i.e. osteoartosis in the distal tarsal joints[17]) |

| Post Legged | Opposite to sickle hocked - extremely straight hock angle | High stress on back of the hock joint and the soft tissue support structures. It can also result in bog and bone spavins |

| Cow Hocked | Medial deviation of the hocks and

accompanied by base wide from hocks to feet. |

Excessive stress on hock can lead to bone and bog spavins |

Hoof Conformation[14][18][edit | edit source]

Hoof conformation and the hoof pastern axis may also interfere with more proximal joints and ligaments. The pastern helps to absorb shock when the hoof lands on the ground. It has an impact on the soundness of the entire leg.[14] The hoof pastern axis refers to an imaginary line which runs from the centre of the fetlock, through the pastern, continuing straight from the coronet to the ground.[19]

- Normal angle: 48 – 55 degrees

- Sloping angle: 45 degrees or less

- Upright angle: 60 degrees or more[19]

Broken back occurs when this imaginary line is broken at the coronet through to the ground surface. The hoof angle is less than the pastern angle.[19] This can cause strain on the tendons and may result in wear on the navicular.

Broken Forward also occurs when this imaginary line is broken at the coronet through to the ground surface. The hoof angle is greater than the pastern angle.[19] This can cause strain on proximal joints.

Gait Assessment[21][22][edit | edit source]

When performing a gait assessment in hand have the horse:[4]

- Walk away from you, past you and towards you

- Trot away from you, past you and towards you

- Walk in a circle with limbs crossing (turn on the forehand)

- Rein back

- Trot on a circle in both directions (usually on the lunge)

It is important to consider the surface you are examining the horse on as this can influence lameness. As a rule of thumb, soft tissue lameness (i.e. tendons and ligaments) will generally show greater lameness in soft or deep surfaces such as a sand arena. Joint lameness is usually more evident on hard ground. Trotting on bricks or concrete may sometimes assist when assessing lameness as you can better hear the foot-fall rhythm.[4]

Grading Lameness[edit | edit source]

There are many types of scales which grade lameness, but as Tabor and Williams note, there is significant variation when veterinarians score lameness.[21] The most widely accepted grading is the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) scale.[23]

| Grades | Degree of lameness |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | No lameness under any conditions |

| Grade 1 | Lameness difficult to observe, not consistently present under any conditions, including weight-bearing, circling on inclines or hard surfaces |

| Grade 2 | Lameness is diffcult to observe at walk or trotting in straight line, but it is consistently present under certain conditions such as weight-bearing or circling on inclines or hard surfaces |

| Grade 3 | Lameness is consistently seen when trotting under all conditions |

| Grade 4 | Lameness is obvious - the horse mobilises with clear head nodding or short stride |

| Grade 5 | Lameness is obvious - the horse has minimal weight-bearing in motion or and at rest. or is unable to move |

Veterinarians also commonly use the lameness locator to assess lameness. This is a machine which analyses movement through motion sensors. It objectively quantifies how a horse moves through space and bears weight.[24]

Range of Motion (ROM)[edit | edit source]

It is very difficult to do an active ROM assessment on most of equine joints in isolation. Thus, animal therapists tend to assess active ROM during functional movements and then test passive ROM. However, reflexes and baited stretches can be used to test cervical and thoracic movements.

Flexion Test[edit | edit source]

Flexion tests are often performed during a lameness examination to exacerbate any lameness that may be present. The animal's leg is held in a flexed position for around a minute. The horse is then trotted off and its gait is analysed for any abnormalities.[25] Applying this sort of pressure to the joint tends to exacerbate problems that may not otherwise be obvious.[26] A horse may take a few uneven steps after the test or be lame for several minutes. However, these tests are not specific, its interpretation is subjective and there is a significant amount of variation between observers.[26] Recalling the baseline level of lameness during both trotting on the lead rope and on the longe line (if appropriate) is crucial to objectively evaluate the results of both flexion tests and diagnostic local anaesthesia.

Active ROM[edit | edit source]

It is very difficult to do an active ROM assessment on most joints in isolation. Thus, equine therapists usually attempt to observe ROM during functional movements and assess passive range in detail. However, baited stretches (i.e. providing a food treat to encourage the horse to move) are used to assess cervical and thoracic movements, as are reflex tests.[21]

Reflexes[edit | edit source]

Ventrodorsal Lift Reflex (Withers Test)[edit | edit source]

This tests thoracic vertebra flexion. To perform this test:[4]

- Apply a firm pressure with fingernails, pen cap or blunt hoof pick to the midline of the level of the horse's girth. This will cause the horse to ‘lift’ the cranial thoracic region

Lateral Reflex[edit | edit source]

This tests lateral flexion. To perform this test:[4]

- Apply a firm pressure with fingernails, pen cap or blunt hoof pick to the bricep femoris line on the contralateral side and around the buttocks. This causes the horse to laterally flex the lumbar and caudal thoracic regions. Consider the horse's ROM

Rounding Reflex[edit | edit source]

This tests lumbar flexion. To perform this test:[4]

- Apply a firm pressure with fingernails, pen cap or blunt hoof pick to the caudal border of biceps femurs bilaterally. Ensure you are standing to the side of the horse and beware of being kicked. The horse will flex. Consider the horse's rotation and ROM

Extension Reflex[edit | edit source]

This tests lumbar or thoracic extension. To perform this test:[4]

- Stand on a box behind the horse, draw your fingers or two hoof picks caudally along the lumbar/ thoracic paravertebral musculature. Observe for quantity and symmetry of movement

Baited Stretches[edit | edit source]

Baited stretches are used to assess active movement of the spine[2] (cervical and cranial thoracic regions). During these movements, the therapist uses a treat to encourage a movement. Remember to compare both sides for lateral movements.

Cervical Spine[edit | edit source]

- Extension - guide the horse's muzzle upwards and forwards with a treat

- Flexion - guide the horse’s muzzle towards its upper chest to effect a nodding movement (at the poll)[22]

Caudal Cervical Spine[edit | edit source]

- Flexion - for lower cervical / upper thoracic flexion, guide the horse’s muzzle down between fetlocks (or observe horse grazing – check for even weight distribution between forelimbs); also guide the horse’s muzzle towards the sternum to check mid-cervical flexion[22]

- Lateral flexion.- guide the muzzle around along horse’s lateral trunk towards the flank and compare range side to side

- Lateral flexion / flexion - guide the muzzle around towards the carpal region and compare range side to side.

Thoracic Spine[edit | edit source]

It is important to note that when testing the caudal cervical spine, you will get some flexion and lateral flexion of the thoracic spine.[4][27]

Passive ROM[edit | edit source]

Cervical Spine[edit | edit source]

- Extension - guide the muzzle upwards and stabilise with one hand gently over C1. Apply a gentle overpressure from underneath the muzzle. Assess end-feel[2]

- Flexion - guide the muzzle towards the upper chest and stabilise with one hand gently over C1. Apply a gentle overpressure to the front of the muzzle. Assess end-feel[2]

- Rotation - stabilise with one hand over C2 and guide the horse’s muzzle toward you on a rotatory axis. Apply gentle overpressure via the muzzle. Compare range of motion and end-feel side to side[2]

- Lateral flexion - motion at each cervical level between C3–C6 can be assessed by palpating the ‘opening’ of the cervical vertebra when an assistant laterally flexes the horse’s neck away from the assessor. Alternatively, you can stabilise over the vertebral body with one had to effectively ‘block’ motion from the chosen level, and gently guide the horse’s muzzle toward you, in a lateral flexion direction. Apply gentle overpressure and assess range of motion and end-feel. You will need to compare sides[4]

Thoracic Spine[edit | edit source]

It is very difficult to assess the passive ROM of the thoracic spine due to deep joint levels, tight connective tissue structures and restrictive facet joint morphology. It is possible to mobilise the wither, but there is very little movement. Some rib springing may be possible depending on soft tissue tone

Lumbar Spine[edit | edit source]

- Unilateral dorsal-ventral mobilisations - standing on a tall box or step, apply a gradual downwards force over the transverse process of each consecutive lumbar vertebra. Repeat on the other side.

- Central dorsal-ventral L5 and L6 - standing on a tall box or step, apply a gradual downwards force over the spinous processes of L5 and L6. Horses with pain in this area (usually ligamentous in origin) will dip away from the pressure. Horses who have no pain will show no response (and no movement should be palpable)

- Lateral mobilisations - standing on a tall box, stabilise the lumbar segment above the testing vertebra and grip the dock of the tail with your other hand. Pull gently on the dock towards you and grade the mobs

Sacroiliac Joint (SIJ)[edit | edit source]

Active Testing[edit | edit source]

- Weight-bearing weight displacement: stand on a box behind the horse (or next to the horse if you suspect it may kick). Palpate the tuber sacrale bilaterally, and have an assistant lift one hindleg. Feel for any cranial shift of the contralateral tub sacrale as the SIJ of the weight-bearing leg assumes its close-packed position. Repeat with the other leg.

- Movement during limb protraction: stand on a box behind the horse (or next to the horse if you suspect it may kick). Palpate the tuber sacrale bilaterally, have an assistant lift one hind leg and stretch it forward. Feel for a slight caudal shift of the contralateral tub sacrale.

Passive Testing[edit | edit source]

On passive testing of the SIJ, a horse's response is an indication of joint irritability, rather than joint restriction or mobility.[4]

- Stand on a box or step next to the horse. Apply a slow, repetitive downwards force on the tuber coxae. Feel for reflex muscle guarding in response to the movement. A horse who does not have pain should allow a soft oscillation of the ilium. Compare to the other side. NB movement of the pelvis also causes movement in the lumbar spine and hip, so it is important to carefully observe where the movement originates.

Peripheral Joints[edit | edit source]

The following table summarises the active and passive ROM tests included in an assessment of the peripheral joints.[4]

| Joint | Active Testing | Passive Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Glenohumeral | Observed through gait | Full flexion can be assessed in this joint, as can adduction and abduction. Internal and external rotation can also be assessed when the elbow is stabilised |

| Elbow | Observed through gait | Full flexion can be assessed, along with external and internal rotation |

| Carpal | Observed through gait | Full extension and flexion may be assessed. With flexion there is slight accessory rotation and lateral glide available |

| Proximal Interphalangeal | Observed through gait | Full flexion and extension may be tested. During flexion, accessory movements of abduction, adduction and rotation can be assessed |

| Distal Interphalageal | Observed through gait | A relative cranial glide of PIII on PII may be achieved. Medial and lateral rotation accessory glides can be assessed |

| Hip | Assessed during gait. To assess abduction and adduction, look at lateral gait work | |

| Stifle | Assessed during gait - look for any locking | Tibiofemoral joint can be assessed in conjunction with the hock for both flexion and extension. Medial and lateral rotation through the tibia may be used to assess ligament integrity |

| Tarsal | Assessed during gait | Full flexion may be assessed. Extension is coupled with the stifle - if you can reach full extension of the hock independently, it can raise suspicions of a rupture of peroneus tertius |

Muscle Strength Testing[edit | edit source]

It is difficult to test individual muscles for strength in equine patients. It is not possible to use the Oxford Scale, so muscle strength is tested globally through functional testing (e.g. a horse who struggles with pushing behind will generally have weak gluteal muscles).

Strength can also be tested by testing the horse's stability. To test stability, lift a leg and shift additional weight to the contralateral limb by gradually pushing against the horse. A normal horse will immediately match the applied force in order to maintain its balance. It is important to note that this does test a number of elements at once, including neural function, balance and the horse's ability to load.

- This test can be done with the front and hind limbs, and while it is very non-specific, it provides information to how comfortable the horse is with loading a particular quadrant.

- If a horse is reluctant to load a particular limb, he will hop sideways, or make postural adjustments with the remaining two weight-bearing limbs. There may also be a lag in response from the horse. This narrows down the region of dysfunction to then be assessed in greater detail

Special Tests[edit | edit source]

Stork Test[edit | edit source]

- When one hind limb is lifted, the SIJ on the contralateral hind limb assumes its close-packed position

- To test for potential SIJ pain, the SIJ is loaded unilaterally by lifting the opposite hind leg into slight abduction, thereby increasing the load on the weight-bearing hind limb. After 60 seconds, the horse is immediately trotted away in a straight line

- The test is positive if the horse exhibits an increased lameness of the WEIGHT-BEARING leg, not the flexed leg

- The test should be repeated on the other side to compare

Palpation[edit | edit source]

When palpating a horse, there are both general and specific features to consider.[3]

General soft tissue palpation will provide information about:[3]

- Temperature

- Irritability

- Muscle tone

- Soft tissue thickening or swelling

- The horse's overall reactivity to touch

Specific muscle palpation occurs after the therapist has developed a hypothesis of which muscle/s may be the primary source of symptoms.[3] You will also palpate bony landmarks. The following table summarises key areas that should be palpated in equine patients.[4]

| Cervical Spine | Fore limb | Spine | Hind limb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Bony landmarks:

Important structures:

|

Bony landmarks:

Important structures

|

Bony landmarks:

Important structures:

|

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 McGowan CM, Stubbs NC, Jull GA. Equine physiotherapy: a comparative view of the science underlying the profession. Equine veterinary journal. 2007 Jan;39(1):90-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Paulekas R, Haussler KK. Principles and practice of therapeutic exercise for horses. Journal of equine veterinary science. 2009 Dec 1;29(12):870-93.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Goff L. Physiotherapy Assessment for the Equine Athlete. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2016 Apr;32(1):31-47.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 Chelin S. Assessment of the Equine Patient Course. Physioplus, 2021.

- ↑ Naccache F, Metzger J, Distl O. Genetic risk factors for osteochondrosis in various horse breeds. Equine Vet J. 2018;50(5):556-63.

- ↑ Miglio A, Cappelli K, Capomaccio S, Mecocci S, Silvestrelli M, Antognoni MT. Metabolic and Biomolecular Changes Induced by Incremental Long-Term Training in Young Thoroughbred Racehorses during First Workout Season. Animals (Basel). 2020;10(2):317.

- ↑ Dakin SG. A review of the healing processes in equine superficial digital flexor tendinopathy. Equine vet. Educ. 2017;29(9):516-20.

- ↑ Crabtree JR. A review of oestrus suppression techniques in mares. Equine Vet Educ. 2021.

- ↑ Wessex Equine. Behavioural problems in performance mares. Available from: http://wessexequine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Hormonal-problems-in-mares-.pdf (accessed 19/4/2021).

- ↑ Kim Hallin. Why are Mares so "Mareish"? Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2BeIZzfnBc [last accessed 21/4/2021]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Equine World UK. Vetting a horse. Available from: https://equine-world.co.uk/info/buying-loaning-selling-horses/buying-a-horse/vetting-a-horse (accessed 19/4/2021).

- ↑ SmartPak. Equine Pre-Purchase Exams. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JDfrYhXw9Y [last accessed 21/4/2021]

- ↑ Finucane LM, Downie A, Mercer C, Greenhalgh SM, Boissonnault WG, Pool-Goudzwaard AL et al. International Framework for Red Flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(7):350-72.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Duberstein KJ. Evaluating horse conformation. Available from: https://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=B1400&title=Evaluating%20Horse%20Conformation#Summary (cited 20/4/2021).

- ↑ Melbye D. Conformation of the horse. Available from: https://extension.umn.edu/horse-care-and-management/conformation-horse#back-1158661 (cited 20/4/2021).

- ↑ Dar KH, Dar SH, Qureshi B. Bog Spavin and Its Management in a Local Horse of Kashmir-a Case Report. SOJ Vet Sci. 2016;2(1):1-2.

- ↑ Björnsdóttir S, Arnason T, Lord P. Culling rate of Icelandic horses due to bone spavin. Acta Vet Scand. 2003;44(3-4):161-9.

- ↑ McIlwraith CW, Anderson TA, Douay P, Goodman NL, Overly LR. Role of conformation in musculoskeletal problems in the racing Thoroughbred and racing quarter horse. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Convention of the American Association of Equine Practitioners, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 21-25 November 2003 (pp. 59-61). American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Genius Equestrian. The Importance Of Hoof Pastern Axis And Working Together To Achieve Good HPA. Available from: https://www.geniusequestrian.com/the-importance-of-hoof-pastern-axis-and-working-together-to-achieve-good-hpa/ (cited 20/4/2021).

- ↑ Olivia Child. How does a horse's conformation affect its quality of movement and long-term structural health? Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5DRpwU98mNI&t=79s [last accessed 21/4/2021]

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Tabor G, Williams J. Objective measurement in equine physiotherapy. Comparative Exercise Physiology. 2020 Feb 5;16(1):21-8.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 McGowan C, Goff L, editors. Animal physiotherapy: assessment, treatment and rehabilitation of animals. John Wiley & Sons; 2016 May 2.

- ↑ American Association of Equine Practitioners. Lameness exams: evaluating the lame horse. Available from: https://aaep.org/horsehealth/lameness-exams-evaluating-lame-horse (cited 20/4/2021).

- ↑ Equinosis Lameness Locator. How it works. Available from: https://equinosis.com/veterinarians/#q-analysis (cited 20/4/2021).

- ↑ Kaneps AJ. Diagnosis of lameness. In: Hinchcliff KW, Kaneps AJ, Geor RJ, editors. Equine sports medicine and surgery. Second Edition. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2014. p239-51.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Marshall JF, Lund DG, Voute LC. Use of a wireless, inertial sensor-based system to objectively evaluate flexion tests in the horse. Equine Vet J Suppl. 2012;(43):8-11.

- ↑ Clayton HM, Kaiser LJ, Lavagnino M, Stubbs NC. Dynamic mobilisations in cervical flexion: Effects on intervertebral angulations. Equine Vet J Suppl. 2010;(38):688-94.