Clinical Frailty Scale: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

'''Level 5 – Living with Mild Frailty''' (previously “Mildly Frail”): These people usually have more evident slowing, and need help in higher-order instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) such as finance, transportation, heavy housework, medications. Typically, mild frailty progressively impairs shopping and walking outside alone, meal preparation, and housekeeping. | '''Level 5 – Living with Mild Frailty''' (previously “Mildly Frail”): These people usually have more evident slowing, and need help in higher-order instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) such as finance, transportation, heavy housework, medications. Typically, mild frailty progressively impairs shopping and walking outside alone, meal preparation, and housekeeping. | ||

'''Level 6 – Living with Moderate Frailty''' (previously “Moderately Frail”) | '''Level 6 – Living with Moderate Frailty''' (previously “Moderately Frail”)They need help with all outside activities and with keeping house. Inside, they often have problems with stairs and need help with bathing and might need minimal assistance (stand-by) with dressing.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":1" /> | ||

'''Level 7 – Living with Severe Frailty''' (previously “Severely Frail”): is characterized by progressive dependence in personal ADLs. Completely dependent on personal care from whatever cause (physical or cognitive). Even so, they seem stable and not at high risk of dying (within six months). People living with severe frailty can be mobile. Progressively taking to bed—but not being largely bedfast—is the hallmark of the progression of severe frailty. | |||

==== Using the Clinical Frailty Scale in People Towards the End of Life ==== | |||

The understanding of what happens at the end of life has evolved in relation to its association with ageing. Older people who are terminally ill are much more likely to receive formal palliative care if they have a diagnosis of cancer than if they have a disease with a recognized terminal phase, such as dementia or heart failure. | |||

'''Level 8 – Living with Very Severe Frailty''' (previously “Very Severely Frail”): These patients are completely dependent, approaching the end of life. Typically, they could not recover even from minor illnesses. is the not uncommon state in which a frail person takes to bed, often for weeks, prior to dying. This is either heralded by an identifiable episode, such as an infection, or the person just slips away, commonly after some days of reduced oral intake. Very severely frail people who die without a single apparent cause typically follow such a trajectory, commonly without much pain or even distress, often, with the exception of impaired bowel function. | |||

'''Level 9 – Terminally Ill:''' Approaching the end of life. This category applies to people with a life expectancy of under 6 months, which are not otherwise evidently frail<ref name=":1" />. This level is notable for being the only level in which the current state trumps the baseline state, in that the terminally ill person might have been operating at any frailty level at baseline. On the Clinical Frailty Scale card, this person is pictured seated in a chair. This reflects the fact that many older adults who are dying with a single system illness—notably cancer—have a reasonable level of function until about the very end. That is why we portray the situation in that way. Even so, if a terminally ill person was completely dependent for personal care at baseline, they would be scored as Level 8.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

== Evidence == | == Evidence == | ||

| Line 57: | Line 63: | ||

=== Miscellaneous<span style="font-size: 20px; font-weight: normal;" class="Apple-style-span"></span> === | === Miscellaneous<span style="font-size: 20px; font-weight: normal;" class="Apple-style-span"></span> === | ||

Since the CFS | Since the CFS is seen as one of the most promising and practical ways of screening frailty in routine assessment and especially in acute care as it combines clinical judgment with objective measurement. It provides valuable information to guide patient care and health policy development. Studies shows that the CFS has been suggested as a tool that can guide the rationing of critical care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies have shown that the CFS is mostly used within geriatric medicine, cardiology, intensive care, general medicine, emergency medicine, surgery, and dialysis. The CFS is also not commonly used to predict patient-oriented measures such as quality of life. Using the CFS to assess the degree of frailty in clinical settings extends beyond evaluating risk to mitigating frailty by understanding disease presentation, acute management, recovery time, and rehabilitation potential. Further research into the potential of this tool is warranted and will likely reveal novel applications to improve medical care of older adults. For example, investigation is warranted into whether implementing CFS in routine practice will improve care. In certain NHS centers in the United Kingdom, the CFS is routinely used to screen all patients over the age of 75 who are admitted to hospital via the Emergency Department [10]. Data from these institutions will be highly valuable in the advancement of frailty research. | ||

Research has been suggested that CFS can be used as a tool that can guide the rationing of critical care resources if they become overwhelmed in the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, we published a guide for using the Clinical Frailty Scale for people new to the scale | Research has been suggested that CFS can be used as a tool that can guide the rationing of critical care resources if they become overwhelmed in the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, we published a guide for using the Clinical Frailty Scale for people new to the scale | ||

Revision as of 16:11, 27 February 2021

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton and Aminat Abolade

Objective[edit | edit source]

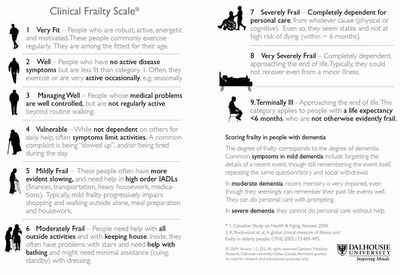

Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is used commonly to assess frailty. The CFS is utilized to predict the outcomes of older people hospitalized with acute illnesses.[1] The CFS is commonly used to predict health outcomes that are significantly associated are mortality, comorbidity, functional decline, mobility, and cognitive decline.

The scale was developed from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging, and it provides a summary tool for clinicians to assess frailty and fitness. Initially, it was scored on a scale from 1 (very fit) to 7 (severely frail). It was modified to a 9-point scale to include very severely frail and terminally ill.[1] It evaluates specific domains, including comorbidity, function, and cognition, to generate a frailty score ranging from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill).[2]

Intended Population[edit | edit source]

The frail elderly population, all individuals over the age of 70 years should be screened for frailty.[2]

Method of Use[edit | edit source]

It can be readily be administered in a clinical setting. Applying the CFS to patients is quick and requires data collection by watching the patient (mobilize), inquiring about their habitual physical activity and ability. The clinicians assess whether the patient can independently perform tasks such as bathing, dressing, housework, going upstairs, going out alone, going shopping, taking care of finances, taking medications, and preparing meals[2].

Technique[edit | edit source]

The scale can be introduced by saying something like: “I’d like to know how you are [your parent is] doing overall.” The clinician can inquire about:

- How the patient moved, functioned, thought, and felt about their health over the last two weeks?

- How active the person is?

- Which medications the patient is taking; experienced clinicians can quickly assay which illnesses are likely present from what medications are being prescribed and/or used?[3]

Using the Clinical Frailty Scale to Grade Degrees of Fitness Prior to the Level of Risk Associated with Frailty[edit | edit source]

Level 1– Very Fit: People who are robust, active, energetic, and motivated. These people commonly exercise regularly. They are among the fittest for their age

Level 2 – Fit: Previously known as well: People who have no intense disease symptoms but are less fit than category 1. Often, they exercise or are very active occasionally, e.g., seasonally.

Level 3 – Managing Well: People whose medical problems are well controlled, but are not regularly active beyond routine walking.

Using the Clinical Frailty Scale to Grade Clinically Meaningfully Increased Risk[edit | edit source]

Key factors for Levels 4 to 7: mobility, function, and cognition. Each level reflects high-order aspects of health: they integrate a lot of information. Mobility problems may be present, for example a sprained ankle, diabetic nerve damage, dehydration, heart failure, kidney damage or pneumonia. In consequence, these key domains are sensitive signs of health but are not very specific. It is the combination of impaired function and impaired mobility, which are commonly accompanied by several illnesses, that makes it likely someone is frail.[3]

Level 4 – previously “Vulnerable” is now Living with Very Mild Frailty-While not dependent on others for daily help, often symptoms limit activities. A common complaint is being “slowed-up” and being tired during the day.

Level 5 – Living with Mild Frailty (previously “Mildly Frail”): These people usually have more evident slowing, and need help in higher-order instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) such as finance, transportation, heavy housework, medications. Typically, mild frailty progressively impairs shopping and walking outside alone, meal preparation, and housekeeping.

Level 6 – Living with Moderate Frailty (previously “Moderately Frail”)They need help with all outside activities and with keeping house. Inside, they often have problems with stairs and need help with bathing and might need minimal assistance (stand-by) with dressing.[3][1]

Level 7 – Living with Severe Frailty (previously “Severely Frail”): is characterized by progressive dependence in personal ADLs. Completely dependent on personal care from whatever cause (physical or cognitive). Even so, they seem stable and not at high risk of dying (within six months). People living with severe frailty can be mobile. Progressively taking to bed—but not being largely bedfast—is the hallmark of the progression of severe frailty.

Using the Clinical Frailty Scale in People Towards the End of Life[edit | edit source]

The understanding of what happens at the end of life has evolved in relation to its association with ageing. Older people who are terminally ill are much more likely to receive formal palliative care if they have a diagnosis of cancer than if they have a disease with a recognized terminal phase, such as dementia or heart failure.

Level 8 – Living with Very Severe Frailty (previously “Very Severely Frail”): These patients are completely dependent, approaching the end of life. Typically, they could not recover even from minor illnesses. is the not uncommon state in which a frail person takes to bed, often for weeks, prior to dying. This is either heralded by an identifiable episode, such as an infection, or the person just slips away, commonly after some days of reduced oral intake. Very severely frail people who die without a single apparent cause typically follow such a trajectory, commonly without much pain or even distress, often, with the exception of impaired bowel function.

Level 9 – Terminally Ill: Approaching the end of life. This category applies to people with a life expectancy of under 6 months, which are not otherwise evidently frail[1]. This level is notable for being the only level in which the current state trumps the baseline state, in that the terminally ill person might have been operating at any frailty level at baseline. On the Clinical Frailty Scale card, this person is pictured seated in a chair. This reflects the fact that many older adults who are dying with a single system illness—notably cancer—have a reasonable level of function until about the very end. That is why we portray the situation in that way. Even so, if a terminally ill person was completely dependent for personal care at baseline, they would be scored as Level 8.[3]

Evidence[edit | edit source]

Reliability[edit | edit source]

Clinical Frailty Scale is a reliable instrument to identify frailty in the emergency department. It might provide ED clinicians with useful information for decision-making with triage, disposition, and treatment.[4] Applying the CFS to patients requires a clinical judgment of the examining clinician and thus may lead to inter-observer variation[1]. The inter-rater reliability of the CFS is generally very good, however, several biases may play a role in scoring, especially with clinicians who are inexperienced using the scale[5]. In light of this, a new classification tree to improve CFS scoring by inexperienced raters has been created.

Validity[edit | edit source]

CFS score is a valid diagnostic instrument to measure frailty in older hospitalized patients and patients in the emergency department.[6] CFS-Korean version is a valid scale for measuring frailty in older Korean patients

This scale has largely not been validated in younger people as disability in younger people (including both acquired, as in spinal cord injury, and life-long, as in intellectual disability) does not have the same meaning for prognosis that it does with age-related disability[3].

Responsiveness[edit | edit source]

Miscellaneous[edit | edit source]

Since the CFS is seen as one of the most promising and practical ways of screening frailty in routine assessment and especially in acute care as it combines clinical judgment with objective measurement. It provides valuable information to guide patient care and health policy development. Studies shows that the CFS has been suggested as a tool that can guide the rationing of critical care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies have shown that the CFS is mostly used within geriatric medicine, cardiology, intensive care, general medicine, emergency medicine, surgery, and dialysis. The CFS is also not commonly used to predict patient-oriented measures such as quality of life. Using the CFS to assess the degree of frailty in clinical settings extends beyond evaluating risk to mitigating frailty by understanding disease presentation, acute management, recovery time, and rehabilitation potential. Further research into the potential of this tool is warranted and will likely reveal novel applications to improve medical care of older adults. For example, investigation is warranted into whether implementing CFS in routine practice will improve care. In certain NHS centers in the United Kingdom, the CFS is routinely used to screen all patients over the age of 75 who are admitted to hospital via the Emergency Department [10]. Data from these institutions will be highly valuable in the advancement of frailty research.

Research has been suggested that CFS can be used as a tool that can guide the rationing of critical care resources if they become overwhelmed in the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, we published a guide for using the Clinical Frailty Scale for people new to the scale

Links[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Mendiratta P, Latif R. Clinical Frailty Scale. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jun 22.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC geriatrics. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-8.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Rockwood K, Theou O. Using the clinical frailty scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Canadian Geriatrics Journal. 2020 Sep;23(3):210.

- ↑ Kaeppeli T, Rueegg M, Dreher-Hummel T, Brabrand M, Kabell-Nissen S, Carpenter CR, Bingisser R, Nickel CH. Validation of the clinical frailty scale for prediction of thirty-day mortality in the emergency department. Annals of emergency medicine. 2020 Sep 1;76(3):291-300.

- ↑ https://www.physiospot.com/research/frailty-scale-classification-tree/ Accessed on 27/2/21

- ↑ Stille K, Temmel N, Hepp J, Herget-Rosenthal S. Validation of the Clinical Frailty Scale for retrospective use in acute care. European Geriatric Medicine. 2020 Dec;11(6):1009-15.