Telerehabilitation and Smartphone Apps in Physiotherapy: Difference between revisions

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) m (Updated editor's code) |

|||

| (361 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editor '''- Oriana Catenazzi, Alicia Rebellato, Hannah Meredith, Aaron Kirk, Martin Fitheridge, Marco Zavagni | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Oriana Catenazzi|Oriana Catenazzi]], [[User:Alicia Rebellato|Alicia Rebellato]], [[User:Hannah Meredith|Hannah Meredith]], [[User:Aaron Kirk|Aaron Kirk]], [[User:Martin Fitherridge|Martin Fitheridge]], [[User:Marco Zavagni|Marco Zavagni ]] as part of [[Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice|Queen Margaret University's Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project]]<br> | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | |||

</div> | |||

== Introduction == | |||

</ | [[Image:MHealth smartphone.jpg|border|right|500x400px]]The rapid evolution of technology has allowed health professionals to begin to adapt to these changes and deliver healthcare in a new, remote fashion. More recently, mHealth has come into play, which refers to the concept of using mobile devices, such as phones, tablets and smartphones in both medicine and public health <ref name="Dicianno et al.">Dicianno, B., Parmanto, B., Fairman, A., Crytzer, T., Yu, D., Pramana, G., Coughenour, D., Petrazzi, A. Perspectives on the evolution of mobile (mHealth) technologies and application to rehabilitation. Physical Therapy:2015:95:397-405</ref>. mHealth is seen as an enabler of change worldwide because of its high reach and low-cost solutions <ref name="Dicianno et al." />. The change towards technology-based practice and more specifically smartphone-based applications is an extremely relevant area for health professionals to effectively communicate and treat a variety of patient groups. Therapeutic compliance has been a topic of clinical concern since the 1970's due to the widespread nature of non-compliance with therapy and rehabilitation programs <ref name="Jin et al.">Jin, J., Sklar, G., Oh, V., Li, S. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient's perspective. Therapeutic and Clinical Risk Management 2008:4:269-286</ref>. It can be proposed that these recent advances in technology can help improve therapeutic outcomes. | ||

= | |||

Specific to physiotherapy home exercise programs, smartphone applications provide a new and emerging way to deliver physiotherapy that promotes active participation from both the physiotherapist and patient throughout the course of treatment. | |||

== Overview of Telerehabilitation == | == Overview of Telerehabilitation == | ||

In recent years, technology has revolutionised all aspects of medical rehabilitation, from developments in the provision of cutting edge treatments to the actual delivery of the specific interventions <ref name="(Brennan et al. 2009)">Brennan DM, Mawson S, Brownsel S. Telerehabilitation: enabling the remote delivery of healthcare, rehabilitation and self management. Studies in Health tech and inform. 2009;123:231.</ref>. Telerehabilitation refers to the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to provide rehabilitation services to people remotely in their home or other environments <ref name="(Brennan et al. 2009)" />. Such services include therapeutic interventions, remote monitoring of progress, education, consultation, training and a means of networking for people with disabilities<ref name="(Theodoros 2008)">Theodoros D, Russell T. Telerehabilitation: current perspectives. Stud Health Technol Inform 2008;131:191.</ref>. | |||

== | Using technology to deliver rehabilitation services has many benefits for not only the clinician but also the patients themselves. It provides the patient with a sense of personal autonomy and empowerment, enabling them to take control in the management of their condition <ref name="(Brennan et al. 2009)" />. In essence they are becoming an active partner rather than a passive participant in their care. It enables access to care for individuals in remote areas or for those who have mobility issues associated with physical impairment, access to transport and socioeconomic factors <ref name="(Theodoros 2008)" />. In addition, it cuts down the associated travel costs and time spent travelling for both the healthcare provider and the patient <ref name="(Kairy et al. 2009)">Kairy D, Lehoux P, Vincent C, Visintin M. A systematic review of clinical outcomes, clinical process, healthcare utilization and costs associated with telerehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(6):427.</ref>. Research has found that the rehabilitation needs for individuals with long-term conditions such as stroke, TBI and other neurological disorders are often unmet in the patient’s local community <ref name="(Theodoros 2008)" />. | ||

== | As telerehabilitation expands, patient continuity of care improves. It enables clinicians to remotely engage and deliver patient care outside of the medical setting, thus eliminating the issue of distance between clinician and patient <ref name="(Brennan et al. 2009)" />. This opportunity to continue rehabilitation within the patient’s own social and vocational environment should lead to greater functional outcomes <ref name="Temkin et al. 1996">Temkin AJ, Ulieny GR, Vesmarovich SH. Telerehabilitation: a perspective of the way technology is going to change the future patient treatment. Rehab management. 1996;9:28.</ref>. | ||

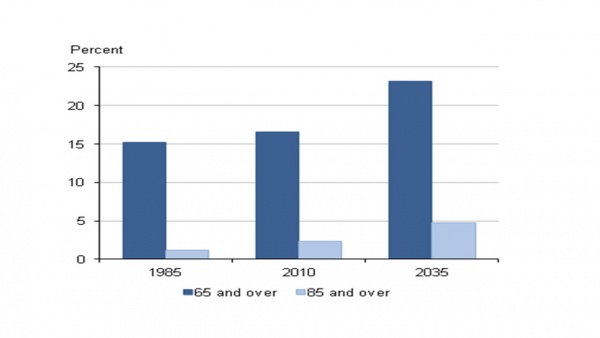

The shift in the global demographics towards an increasing elderly population brings with it an associated increase in chronic health conditions <ref name="(Dexter et ak, 2010)">Dexter PR, Miller DK, Clark DO, Weiner M, Harris LE, Livin L, Mysers I, Shaw D, Blue L, Kunzer J, Overhage JM. Preparing for an aging population and improving chronic disease management. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:162.</ref>. This highlights the need for changes to be made in the delivery of rehabilitation services with the incorporation of self-management strategies and technology. The predicted growth in the elderly population, individuals aged 65 and over, by 2035, will account for 23% of the total population in the UK <ref name="(Office for National Statistics 2012)">Office for National Statistics. Population Ageing in the United Kingdom, its Constituent Countries and the European Union. Office for National Statistics, 2012.</ref>.<br> | |||

<div class="row"> | |||

<div class="col-md-4">'''Predicted growth in the elderly population in the UK'''</div> | |||

<div class="col-md-8">[[Image:Growing elderly population.jpg|600px|(National Statistics 2012)]]</div> | |||

</div> | |||

Growing numbers of elderly people have an impact on the NHS, incurring considerable health costs due to the growing demand for treatments <ref name="(Cracknell 2010)">Cracknell R. The ageing population. House of Commons Library Research. 2010.</ref>. It is hoped that by integrating telehealth measures, these costs will be reduced. Kortke et al (2006) found a significant improvement in patient outcomes when using telerehabilitation with a 58% reduction in cost in comparison to in-patient rehabilitation <ref name="(Kortke et al. 2006)">Kortke H, Stromeyer H, Zittermann A, Buhr N, Zimmermann E, Wienecke E. New east-westfalian postoperative therapy concept: A telemedicine guide for the study of ambulatory rehabilitation of patients after cardiac surgery. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12(4):475.</ref>. | |||

== | Generally, most systematic reviews that have been carried out investigating the efficacy of telerehabilitation report the patient’s perspective on its use as a positive experience with significant clinical outcomes <ref name="(Rogante et al. 2010)">Rogante M, Grigioni M, Cordella D, Giacomozzi C. Ten years of telerehabilitation: A literature overview of technologies and clinical applications. NeuroRehabilitation. 2010;27:287.</ref>. The hope for the future is to continue to develop and use new, innovative technologies that will transform current practice and make telerehabilitation an integral part of healthcare <ref name="(Theodoros 2008)" />. | ||

=== | === Progression of Technology === | ||

= | Telerehabilitation for physical disorders has been short-lived. The problems that arose for this type of rehabilitation stemmed from the difficulties it imposed on the so-called “hands-on” therapies, particularly physiotherapy and occupational therapy <ref name="(Theodoros 2008)" />. However, as technology has progressed in healthcare, the possibilities for effective telerehabilitation in therapies such as these have improved. | ||

<div class="row"> | |||

<div class="col-md-4">'''Progression of technology in telerehabilitation'''</div> | |||

<div class="col-md-8">[[Image:Progression of technology.jpg|center|600x350px]]</div> | |||

</div> | |||

Early research into telerehabilitation was introduced with small pilot studies. In some of the first projects, clinicians used the telephone to provide follow up and to administer self-assessment measures <ref>Korner-Bitensky N, Wood-Dauphinee S. Barthel Index information elicited over the telephone. Is it reliable?, American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1995;74(1):9.</ref>. From this, telerehabilitation continued to progress into the 1980s with pre-recorded video material for client use and interaction <ref>Wertz RT, Dronkers NF, Bernstein-Ellis E, Sterling LK, Shubitowski Y, Elman R, Shenaut GK, Knight RT, Deal JL. Potential of telephonic and television technology for appraising and diagnosing neurogenic communication disorders in remote settings. Aphasiology. 1992;6:195.</ref>. | |||

Eventually, live interactive video conferencing was introduced <ref>Brennan D, Georgeadis A, Baron C, Barker L. The effect of videoconference-based telerehab on story retelling performance by brain injured subjects and its implications for remote speech-language therapy. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health. 2004;10(2):147.</ref>. The potential uses for video conferencing in healthcare and telerehabilitation became apparent in the 1990s with many projects being carried out in physiotherapy. In a randomised control trial (RCT) by Russell and colleagues (2011), the efficacy of this internet-based telerehabilitation system was assessed versus conventional physiotherapy in the provision of outpatient rehabilitation to patients who had received total knee replacement (TKR). Comparable results were reported with the two rehabilitation methods and patients were satisfied with the telerehabilitation treatment provided <ref>Russell TG, Buttrum P, Wootton R, Jull GA. Internet-based outpatient telerehabilitation for patients following total knee arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2011;93(2):113.</ref>. | |||

The use of videoconferencing allows for the provision of consultations, diagnostic assessments and delivery of treatment interventions as well as providing verbal and visual interaction between participants. However, problems lay initially in the inability to measure participant’s physical performance; for example in physiotherapy, these would include measures such as range of motion and gait. This was soon overcome by measurement tools that were able to objectively quantify participant’s physical performance <ref name="(Theodoros 2008)" />. Developments continued to be made using sensor and remote monitoring technologies for within the home which further enhanced the benefits of these new innovative technologies of telerehabilitation <ref name="(Brennan et al. 2009)" />. These developments provided a means of home-based exercise monitoring by the patient and the rehab professional while also enabling the professional to track patient compliance to specific exercise programmes <ref>Zheng K, Padman R, Johnson MP, Diamond HS. Understanding technology adoption in clinical care: clinician adoption behaviour of a point-of-care reminder system. Int J Med Inf. 2005:74(7-8):535.</ref>. | |||

Virtual environments are another technological method introduced to healthcare. These allow users to interact with computer generated environments in real time <ref name="(Theodoros 2008)" />. Virtual reality begins with real world scenes which are then virtualized, thus mimicking real world environments <ref>Cooper DB, Wilis A, Andrews S, Baker J, Cao Y, Han D, Kang K, Kong W, Leymarie F, Orriols X, Vote E, Joukowsky M, Kimia B, Laidlaw D, Mumford D, Velipasalar S. Assembling virtual pots from 3D measurements of their fragments. Proceedings of VAST. 2001:241.</ref>. It enables healthcare professionals to design environments which can be used in areas such as surgery, physical rehabilitation and education and training. | |||

In recent years, smartphones have revolutionised communication within the medical setting. This modernisation is allowing the opportunity to provide medical support when and where people need it. Recently, it has been reported that half of smartphone owners use their devices to get health information <ref>Kamel-Boulos M, Brewer A, Karimkhani C, Buller D, Dellavalle R. Mobile medical and health apps: state of the art, concerns, regulatory control and certification. J of Public Health Inform. 2014;5(3):229.</ref>, with one fifth of smartphone users actually using health related applications (apps) <ref>Fox S, Duggan M. Mobile Health 2012. Washington, DC, Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project 2012. Available at http://pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_MobileHealth2012_FINAL.pdf</ref>. There are a wide range of mobile apps available for healthcare professionals, medical students, patients and the general public <ref name="(Kamel-Boulos 2014)">Kamel-Boulos M, Brewer A, Karimkhani C, Buller D, Dellavalle R. Mobile medical and health apps: state of the art, concerns, regulatory control and certification. J of Public Health Inform. 2014;5(3):229.</ref>. | |||

== Applications for Specific Conditions == | |||

In the innovation of mobile technology, mHealth (mobile health) in particular is helping with chronic disease management, empowering the elderly, reminding people to take medication at the right time, undergo scheduled exercise, extending service to underserved areas and improving health outcomes <ref>West, D. How Mobile devices are Transforming Healthcare.Issues in Technology Innovation 2012; (18): . https://vacloud.us/sandbox/groups/5069/wiki/a69cb/attachments/1ddb8/Brookings%20-%20How%20Mobile%20Devices%20are%20Transforming%20Healthcare.pdf (accessed 25 November 2015).</ref>. There is currently a vast range of mobile apps, interactive tools and podcasts that cater to an array of healthcare conditions and disabilities both formal and informal, recognized and promoted by the NHS <ref name="NHS Choices">NHS Choices. Tools - Interactive tools, smartphone apps and podcasts. http://www.nhs.uk/tools/pages/toolslibrary.aspx?Tag=&Page=1 (accessed 3 December 2015).</ref>. In 2012, there were an estimated 40,000 health-related apps available <ref>NHS Choices. Health Tools: Interactive tools, smartphone apps and podcasts. http://www.nhs.uk/tools/pages/toolslibrary.aspx?Tag=&Page=1 (accessed 25 November 2015).</ref>. Those formal in nature allow patients to record and send health measures and send them electronically to physicians and/or specialists. | |||

As such the National Delivery Plan 2012 documents that by deploying technology in healthcare “provides an opportunity to treat patients in new ways and helps manage rising costs and demand” <ref name="Scottish Government0">Scottish Government. A National Telehealth and Telecare Delivery Plan for Scotland to 2015 – Driving Improvement, Integration and Innovation. http://www.gov.scot/resource/0041/00411586.pdf (accessed 25 November 2015).</ref>. Theoretically, this allows for greater access to healthcare provisions, availability of care and supports self management and prevention in routine care, thereby reducing unnecessary admissions (therefore speeding up the treatment of patients requiring medical intervention) and helps to reduce healthcare costs in an aging population <ref>Scottish Centre for Telehealth & Telecare. Supporting Improvement, Integration and Innovation - Business Plan 2012-2015. http://sctt.org.uk/programmes/ (accessed 25 November 2015).</ref>.<br> | |||

Currently, there are a number of generic healthcare apps available for download which cater for many different acute and chronic conditions. Which have either been approved by the NHS or the private sector. Not only that, but there are also many that function as self assessment, screening and testing tools and symptom checkers, goal setters and treatment/exercise logs and prescribers. Others are collections of support videos or advice. | |||

== | == Using Smartphone Applications in Physiotherapy == | ||

Following an understanding of what motivates patient behaviour and adherence to healthcare treatments discussed above, this section will look more specifically at factors that have an impact on the patient’s ability to respond and agree to treatment in the form of home exercise programmes (HEPs) as well as the potential for healthcare and physiotherapy smartphone applications to deepen the patient-physiotherapist relationship and improve overall rehabilitation of the patient in a musculoskeletal setting. <br> | |||

In an outpatient setting, a HEP is tailored to an individual patient and targets their specific problems, as identified by the Physiotherapist. This exercise schedule, modified with repetitions, sets and/or additional strengthening/ endurance components, is to be performed by the patient in their home environment between treatment sessions with the Physiotherapist. Continuation of training at home ensures that a patient will begin to improve and that their progress can be monitored throughout time. The continued tailoring of the HEP from each session by the physiotherapist must be complemented by the patient’s continued determination and trust in their shifting programme. The understanding and commitment between both the patient and their physiotherapist to achieve both short-term and long-term goals indicates a better outcome for the patient once they are back to (or potentially better than) their baseline. However, various reports monitoring patient compliance with and to a HEP show non-adherence rates to be as low as approximately 20% (<ref name="DiMatteo 2004">DiMatteo RM. Variation in Patients’ Adherence to Medical Recommendations: A Quantitative Review of 50 Years of Research. Medical Care 2004; 42: 200-9.</ref>; <ref name="Dean and Smith 2005">Dean SG, Smith, JA, Payne S, Weinman J. Managing time: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of patients’ and physiotherapists’ perceptions of adherence to therapeutic exercise for low back pain. Disability and Rehabilitation 2005; 27: 625-36.</ref>). | |||

In addition to factors and models described above such as goal setting, self-efficacy, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (self-determination theory) and the transtheoretical model there are other circumstances which can affect the ability of patients to respond positively to a home exercise programme. While demographics such as age and gender have been shown to have little effect on these rates (<ref name="DiMatteo 2004" />), there are a few factors that have been discovered and discussed in the research that may affect compliance such as: | |||

* Low levels of physical activity at baseline | |||

* Anxiety, depression and pain | |||

* Poor social support | |||

* Greater perceived barriers to exercise | |||

* Poor understanding about their condition | |||

* Difficult to commit to the time needed to exercise | |||

* High cost of treatment | |||

<br>Through a greater understanding of the patient perspective, Physiotherapists alongside the multi-disciplinary team can work to target and ensure that patients are kept on the right track and allow greater improvement of quality of life. However, with an adherence rate of 20% keeping most patients isolated from full recovery, what can we do to strengthen the patient-physiotherapist relationship? | |||

This is where the potential of telerehabilitation comes in. Discussed in the beginning sections, telerehabilitation is the modernization of healthcare-related treatments and services. Mobile technologies are still fairly recent and just starting to emerge; therefore there is not a wealth information or research on their use or advantages.<br> | |||

In | == Data Protection == | ||

With the increasing number of smartphone applications and rapid progression of telerehabilitation services available worldwide, it is important the the physiotherapist is aware of the quality and protection that the software offers. In the UK, compliance with the [http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/29/contents Data Protection Act] is a minimum standard to protect your information and rights. The following table describes key rules so that information is:[[Image:Data protection .png|center|400x300px|(Scottish Government 2015)]]<br>Many applications provide a global sample of physiotherapy home exercise programs available through smartphone applications. Under the ‘terms and conditions’ and ‘privacy policy’ section of each application, they specifically describe data protection as well as liability concerns for using their software. Importantly, they all describe in some form that the company is not to be held liable for any health concerns that have occured while using the application. The physiotherapist must ensure that they are adequately insured.This is extremely important for the all applications, but specifically PhysioAdvisor as the patient can utilize resources to assist with self-diagnosis and have independent control over creating their own exercise program. It is important for both patients and physiotherapists to make themselves aware of the terms and conditions when using external applications. | |||

=== | === Cost Effectiveness === | ||

== | The common occurrence of patients’ failing to attend scheduled appointments results in loss of revenue, underutilization of the healthcare system as well as prolonged waiting lists<ref>Geraghty, M., Glynn, F., Amin, M., Kinsella, J. Patient mobile telephone 'text' reminder: a novel way to reduce non-attendance at the ENT out-patient clinic. Journal of Laryngology & Oncology 2007:122:296-298</ref>. A smartphone application is a potential method to prevent cancellations through effective reminder systems. Each application costs a small renewable fee which is based on the number of physiotherapists and or clinics that require a subscription . Important to note is that therapeutic non-compliance has been associated with excess urgent care visits, hospitalizations and higher treatment costs <ref name="Jin et al." />. These applications can be seen as an investment for the clinic or hospital to help increase efficiency, reduce cancellations and prevent future health care demand.<ref name="Scottish Government0" />. While these applications provide an exciting new outlet for physiotherapy to proceed towards in the future, there are some barriers and limitations to the successful implementation of these new technologies. Through a discussion and understanding of these obstacles, further research can be directed at ways to improve and adapt technologies to suit the current needs of healthcare.<br> | ||

== | == Concluding Remarks == | ||

= | With the ever enhancing realm of technology and mHeath applications, the future generation of physiotherapists must be aware of the evolving changes in technology to make physiotherapy an interactive environment with the patient. This will support an increase in motivation and facilitate participation in a home exercise program. As one review discovered, non-compliance remains a major issue in improving healthcare outcomes despite many studies highlighting this ongoing issue over the years <ref name="Jin et al." />. The new face of physiotherapy applications can facilitate patient adherence by creating an interactive exercise environment that promotes self-efficacy and behavior change through enhanced communication, goal setting and progress reporting means. As this wiki has highlighted, there are many links that can be made between the models of behavior change and some of the smartphone applications discussed here, however due to wide variation in terms of study designs and applications, it is difficult to pinpoint potential influences of mobile-phone based strategies on physical activity behavior <ref name="Monroe et al.">Monroe, C., Thompson, D., Bassett, D., Fitzhugh, E., Raynor, H. Usability of mobile phones in physical-activity related research: a systematic review. American Journal of Health Education 2015:46:196-206</ref>. Additionally, the effectiveness of smartphone applications to improve health behaviours is an emerging field of research <ref name="Kirwan et al. 2012">Kirwan M, Duncan, MJ, Vandelanotte C, Mummery, WK. Using Smartphone Technology to monitor physical activity in the 10,000 Steps program: a matched case-control trial. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14: e55.</ref>. [[Image:Smartphone .jpg|right]]Government highlights for our way forward, we need to improve sustainability and value by establishing a baseline, and developing consistent outcome measures and indicators to track the impact of telehealth and telecare on working practices, productivity and resource use <ref name="Scottish Government0" />. Future research is necessary to focus on these novel physiotherapy applications and the effect on patient behavior change and patient experience. Research should also target physiotherapy programs administered via these applications to identify any advances in rehabilitation and home exercise programs. | ||

== References == | |||

<references /><br> | |||

== <span style="font-size: 19.92px; line-height: 1.5em; background-color: initial;">References</span> == | == <span style="font-size: 19.92px; line-height: 1.5em; background-color: initial;">References</span> == | ||

<references />. | |||

[[Category:Health_Promotion]] | |||

[[Category:Exercise_Therapy]] | |||

[[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | |||

[[Category:Physical_Activity]] | |||

[[Category:Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Exercise Therapy]] | |||

[[Category:Rehabilitation Foundations]] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:53, 16 June 2020

Original Editor - Oriana Catenazzi, Alicia Rebellato, Hannah Meredith, Aaron Kirk, Martin Fitheridge, Marco Zavagni as part of Queen Margaret University's Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Oriana Catenazzi, Alicia Rebellato, Aaron Kirk, Hannah Meredith, Marco Zavagni, Martin Fitheridge, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Tony Lowe and Michelle Lee

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The rapid evolution of technology has allowed health professionals to begin to adapt to these changes and deliver healthcare in a new, remote fashion. More recently, mHealth has come into play, which refers to the concept of using mobile devices, such as phones, tablets and smartphones in both medicine and public health [1]. mHealth is seen as an enabler of change worldwide because of its high reach and low-cost solutions [1]. The change towards technology-based practice and more specifically smartphone-based applications is an extremely relevant area for health professionals to effectively communicate and treat a variety of patient groups. Therapeutic compliance has been a topic of clinical concern since the 1970's due to the widespread nature of non-compliance with therapy and rehabilitation programs [2]. It can be proposed that these recent advances in technology can help improve therapeutic outcomes.

Specific to physiotherapy home exercise programs, smartphone applications provide a new and emerging way to deliver physiotherapy that promotes active participation from both the physiotherapist and patient throughout the course of treatment.

Overview of Telerehabilitation[edit | edit source]

In recent years, technology has revolutionised all aspects of medical rehabilitation, from developments in the provision of cutting edge treatments to the actual delivery of the specific interventions [3]. Telerehabilitation refers to the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to provide rehabilitation services to people remotely in their home or other environments [3]. Such services include therapeutic interventions, remote monitoring of progress, education, consultation, training and a means of networking for people with disabilities[4].

Using technology to deliver rehabilitation services has many benefits for not only the clinician but also the patients themselves. It provides the patient with a sense of personal autonomy and empowerment, enabling them to take control in the management of their condition [3]. In essence they are becoming an active partner rather than a passive participant in their care. It enables access to care for individuals in remote areas or for those who have mobility issues associated with physical impairment, access to transport and socioeconomic factors [4]. In addition, it cuts down the associated travel costs and time spent travelling for both the healthcare provider and the patient [5]. Research has found that the rehabilitation needs for individuals with long-term conditions such as stroke, TBI and other neurological disorders are often unmet in the patient’s local community [4].

As telerehabilitation expands, patient continuity of care improves. It enables clinicians to remotely engage and deliver patient care outside of the medical setting, thus eliminating the issue of distance between clinician and patient [3]. This opportunity to continue rehabilitation within the patient’s own social and vocational environment should lead to greater functional outcomes [6].

The shift in the global demographics towards an increasing elderly population brings with it an associated increase in chronic health conditions [7]. This highlights the need for changes to be made in the delivery of rehabilitation services with the incorporation of self-management strategies and technology. The predicted growth in the elderly population, individuals aged 65 and over, by 2035, will account for 23% of the total population in the UK [8].

Growing numbers of elderly people have an impact on the NHS, incurring considerable health costs due to the growing demand for treatments [9]. It is hoped that by integrating telehealth measures, these costs will be reduced. Kortke et al (2006) found a significant improvement in patient outcomes when using telerehabilitation with a 58% reduction in cost in comparison to in-patient rehabilitation [10].

Generally, most systematic reviews that have been carried out investigating the efficacy of telerehabilitation report the patient’s perspective on its use as a positive experience with significant clinical outcomes [11]. The hope for the future is to continue to develop and use new, innovative technologies that will transform current practice and make telerehabilitation an integral part of healthcare [4].

Progression of Technology[edit | edit source]

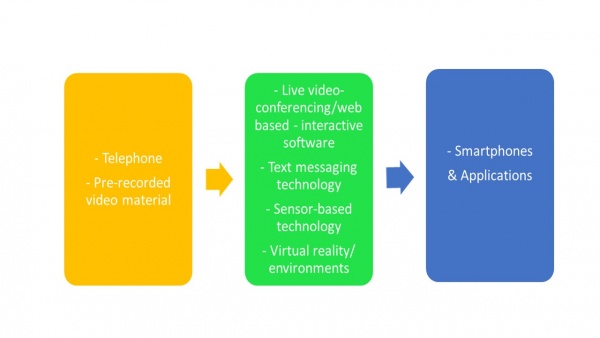

Telerehabilitation for physical disorders has been short-lived. The problems that arose for this type of rehabilitation stemmed from the difficulties it imposed on the so-called “hands-on” therapies, particularly physiotherapy and occupational therapy [4]. However, as technology has progressed in healthcare, the possibilities for effective telerehabilitation in therapies such as these have improved.

Early research into telerehabilitation was introduced with small pilot studies. In some of the first projects, clinicians used the telephone to provide follow up and to administer self-assessment measures [12]. From this, telerehabilitation continued to progress into the 1980s with pre-recorded video material for client use and interaction [13].

Eventually, live interactive video conferencing was introduced [14]. The potential uses for video conferencing in healthcare and telerehabilitation became apparent in the 1990s with many projects being carried out in physiotherapy. In a randomised control trial (RCT) by Russell and colleagues (2011), the efficacy of this internet-based telerehabilitation system was assessed versus conventional physiotherapy in the provision of outpatient rehabilitation to patients who had received total knee replacement (TKR). Comparable results were reported with the two rehabilitation methods and patients were satisfied with the telerehabilitation treatment provided [15].

The use of videoconferencing allows for the provision of consultations, diagnostic assessments and delivery of treatment interventions as well as providing verbal and visual interaction between participants. However, problems lay initially in the inability to measure participant’s physical performance; for example in physiotherapy, these would include measures such as range of motion and gait. This was soon overcome by measurement tools that were able to objectively quantify participant’s physical performance [4]. Developments continued to be made using sensor and remote monitoring technologies for within the home which further enhanced the benefits of these new innovative technologies of telerehabilitation [3]. These developments provided a means of home-based exercise monitoring by the patient and the rehab professional while also enabling the professional to track patient compliance to specific exercise programmes [16].

Virtual environments are another technological method introduced to healthcare. These allow users to interact with computer generated environments in real time [4]. Virtual reality begins with real world scenes which are then virtualized, thus mimicking real world environments [17]. It enables healthcare professionals to design environments which can be used in areas such as surgery, physical rehabilitation and education and training.

In recent years, smartphones have revolutionised communication within the medical setting. This modernisation is allowing the opportunity to provide medical support when and where people need it. Recently, it has been reported that half of smartphone owners use their devices to get health information [18], with one fifth of smartphone users actually using health related applications (apps) [19]. There are a wide range of mobile apps available for healthcare professionals, medical students, patients and the general public [20].

Applications for Specific Conditions[edit | edit source]

In the innovation of mobile technology, mHealth (mobile health) in particular is helping with chronic disease management, empowering the elderly, reminding people to take medication at the right time, undergo scheduled exercise, extending service to underserved areas and improving health outcomes [21]. There is currently a vast range of mobile apps, interactive tools and podcasts that cater to an array of healthcare conditions and disabilities both formal and informal, recognized and promoted by the NHS [22]. In 2012, there were an estimated 40,000 health-related apps available [23]. Those formal in nature allow patients to record and send health measures and send them electronically to physicians and/or specialists.

As such the National Delivery Plan 2012 documents that by deploying technology in healthcare “provides an opportunity to treat patients in new ways and helps manage rising costs and demand” [24]. Theoretically, this allows for greater access to healthcare provisions, availability of care and supports self management and prevention in routine care, thereby reducing unnecessary admissions (therefore speeding up the treatment of patients requiring medical intervention) and helps to reduce healthcare costs in an aging population [25].

Currently, there are a number of generic healthcare apps available for download which cater for many different acute and chronic conditions. Which have either been approved by the NHS or the private sector. Not only that, but there are also many that function as self assessment, screening and testing tools and symptom checkers, goal setters and treatment/exercise logs and prescribers. Others are collections of support videos or advice.

Using Smartphone Applications in Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Following an understanding of what motivates patient behaviour and adherence to healthcare treatments discussed above, this section will look more specifically at factors that have an impact on the patient’s ability to respond and agree to treatment in the form of home exercise programmes (HEPs) as well as the potential for healthcare and physiotherapy smartphone applications to deepen the patient-physiotherapist relationship and improve overall rehabilitation of the patient in a musculoskeletal setting.

In an outpatient setting, a HEP is tailored to an individual patient and targets their specific problems, as identified by the Physiotherapist. This exercise schedule, modified with repetitions, sets and/or additional strengthening/ endurance components, is to be performed by the patient in their home environment between treatment sessions with the Physiotherapist. Continuation of training at home ensures that a patient will begin to improve and that their progress can be monitored throughout time. The continued tailoring of the HEP from each session by the physiotherapist must be complemented by the patient’s continued determination and trust in their shifting programme. The understanding and commitment between both the patient and their physiotherapist to achieve both short-term and long-term goals indicates a better outcome for the patient once they are back to (or potentially better than) their baseline. However, various reports monitoring patient compliance with and to a HEP show non-adherence rates to be as low as approximately 20% ([26]; [27]).

In addition to factors and models described above such as goal setting, self-efficacy, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (self-determination theory) and the transtheoretical model there are other circumstances which can affect the ability of patients to respond positively to a home exercise programme. While demographics such as age and gender have been shown to have little effect on these rates ([26]), there are a few factors that have been discovered and discussed in the research that may affect compliance such as:

- Low levels of physical activity at baseline

- Anxiety, depression and pain

- Poor social support

- Greater perceived barriers to exercise

- Poor understanding about their condition

- Difficult to commit to the time needed to exercise

- High cost of treatment

Through a greater understanding of the patient perspective, Physiotherapists alongside the multi-disciplinary team can work to target and ensure that patients are kept on the right track and allow greater improvement of quality of life. However, with an adherence rate of 20% keeping most patients isolated from full recovery, what can we do to strengthen the patient-physiotherapist relationship?

This is where the potential of telerehabilitation comes in. Discussed in the beginning sections, telerehabilitation is the modernization of healthcare-related treatments and services. Mobile technologies are still fairly recent and just starting to emerge; therefore there is not a wealth information or research on their use or advantages.

Data Protection[edit | edit source]

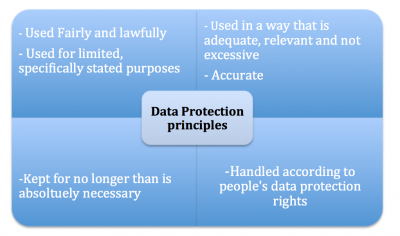

With the increasing number of smartphone applications and rapid progression of telerehabilitation services available worldwide, it is important the the physiotherapist is aware of the quality and protection that the software offers. In the UK, compliance with the Data Protection Act is a minimum standard to protect your information and rights. The following table describes key rules so that information is:

Many applications provide a global sample of physiotherapy home exercise programs available through smartphone applications. Under the ‘terms and conditions’ and ‘privacy policy’ section of each application, they specifically describe data protection as well as liability concerns for using their software. Importantly, they all describe in some form that the company is not to be held liable for any health concerns that have occured while using the application. The physiotherapist must ensure that they are adequately insured.This is extremely important for the all applications, but specifically PhysioAdvisor as the patient can utilize resources to assist with self-diagnosis and have independent control over creating their own exercise program. It is important for both patients and physiotherapists to make themselves aware of the terms and conditions when using external applications.

Cost Effectiveness[edit | edit source]

The common occurrence of patients’ failing to attend scheduled appointments results in loss of revenue, underutilization of the healthcare system as well as prolonged waiting lists[28]. A smartphone application is a potential method to prevent cancellations through effective reminder systems. Each application costs a small renewable fee which is based on the number of physiotherapists and or clinics that require a subscription . Important to note is that therapeutic non-compliance has been associated with excess urgent care visits, hospitalizations and higher treatment costs [2]. These applications can be seen as an investment for the clinic or hospital to help increase efficiency, reduce cancellations and prevent future health care demand.[24]. While these applications provide an exciting new outlet for physiotherapy to proceed towards in the future, there are some barriers and limitations to the successful implementation of these new technologies. Through a discussion and understanding of these obstacles, further research can be directed at ways to improve and adapt technologies to suit the current needs of healthcare.

Concluding Remarks [edit | edit source]

With the ever enhancing realm of technology and mHeath applications, the future generation of physiotherapists must be aware of the evolving changes in technology to make physiotherapy an interactive environment with the patient. This will support an increase in motivation and facilitate participation in a home exercise program. As one review discovered, non-compliance remains a major issue in improving healthcare outcomes despite many studies highlighting this ongoing issue over the years [2]. The new face of physiotherapy applications can facilitate patient adherence by creating an interactive exercise environment that promotes self-efficacy and behavior change through enhanced communication, goal setting and progress reporting means. As this wiki has highlighted, there are many links that can be made between the models of behavior change and some of the smartphone applications discussed here, however due to wide variation in terms of study designs and applications, it is difficult to pinpoint potential influences of mobile-phone based strategies on physical activity behavior [29]. Additionally, the effectiveness of smartphone applications to improve health behaviours is an emerging field of research [30].

Government highlights for our way forward, we need to improve sustainability and value by establishing a baseline, and developing consistent outcome measures and indicators to track the impact of telehealth and telecare on working practices, productivity and resource use [24]. Future research is necessary to focus on these novel physiotherapy applications and the effect on patient behavior change and patient experience. Research should also target physiotherapy programs administered via these applications to identify any advances in rehabilitation and home exercise programs.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dicianno, B., Parmanto, B., Fairman, A., Crytzer, T., Yu, D., Pramana, G., Coughenour, D., Petrazzi, A. Perspectives on the evolution of mobile (mHealth) technologies and application to rehabilitation. Physical Therapy:2015:95:397-405

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jin, J., Sklar, G., Oh, V., Li, S. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient's perspective. Therapeutic and Clinical Risk Management 2008:4:269-286

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Brennan DM, Mawson S, Brownsel S. Telerehabilitation: enabling the remote delivery of healthcare, rehabilitation and self management. Studies in Health tech and inform. 2009;123:231.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Theodoros D, Russell T. Telerehabilitation: current perspectives. Stud Health Technol Inform 2008;131:191.

- ↑ Kairy D, Lehoux P, Vincent C, Visintin M. A systematic review of clinical outcomes, clinical process, healthcare utilization and costs associated with telerehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(6):427.

- ↑ Temkin AJ, Ulieny GR, Vesmarovich SH. Telerehabilitation: a perspective of the way technology is going to change the future patient treatment. Rehab management. 1996;9:28.

- ↑ Dexter PR, Miller DK, Clark DO, Weiner M, Harris LE, Livin L, Mysers I, Shaw D, Blue L, Kunzer J, Overhage JM. Preparing for an aging population and improving chronic disease management. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:162.

- ↑ Office for National Statistics. Population Ageing in the United Kingdom, its Constituent Countries and the European Union. Office for National Statistics, 2012.

- ↑ Cracknell R. The ageing population. House of Commons Library Research. 2010.

- ↑ Kortke H, Stromeyer H, Zittermann A, Buhr N, Zimmermann E, Wienecke E. New east-westfalian postoperative therapy concept: A telemedicine guide for the study of ambulatory rehabilitation of patients after cardiac surgery. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12(4):475.

- ↑ Rogante M, Grigioni M, Cordella D, Giacomozzi C. Ten years of telerehabilitation: A literature overview of technologies and clinical applications. NeuroRehabilitation. 2010;27:287.

- ↑ Korner-Bitensky N, Wood-Dauphinee S. Barthel Index information elicited over the telephone. Is it reliable?, American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1995;74(1):9.

- ↑ Wertz RT, Dronkers NF, Bernstein-Ellis E, Sterling LK, Shubitowski Y, Elman R, Shenaut GK, Knight RT, Deal JL. Potential of telephonic and television technology for appraising and diagnosing neurogenic communication disorders in remote settings. Aphasiology. 1992;6:195.

- ↑ Brennan D, Georgeadis A, Baron C, Barker L. The effect of videoconference-based telerehab on story retelling performance by brain injured subjects and its implications for remote speech-language therapy. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health. 2004;10(2):147.

- ↑ Russell TG, Buttrum P, Wootton R, Jull GA. Internet-based outpatient telerehabilitation for patients following total knee arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2011;93(2):113.

- ↑ Zheng K, Padman R, Johnson MP, Diamond HS. Understanding technology adoption in clinical care: clinician adoption behaviour of a point-of-care reminder system. Int J Med Inf. 2005:74(7-8):535.

- ↑ Cooper DB, Wilis A, Andrews S, Baker J, Cao Y, Han D, Kang K, Kong W, Leymarie F, Orriols X, Vote E, Joukowsky M, Kimia B, Laidlaw D, Mumford D, Velipasalar S. Assembling virtual pots from 3D measurements of their fragments. Proceedings of VAST. 2001:241.

- ↑ Kamel-Boulos M, Brewer A, Karimkhani C, Buller D, Dellavalle R. Mobile medical and health apps: state of the art, concerns, regulatory control and certification. J of Public Health Inform. 2014;5(3):229.

- ↑ Fox S, Duggan M. Mobile Health 2012. Washington, DC, Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project 2012. Available at http://pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_MobileHealth2012_FINAL.pdf

- ↑ Kamel-Boulos M, Brewer A, Karimkhani C, Buller D, Dellavalle R. Mobile medical and health apps: state of the art, concerns, regulatory control and certification. J of Public Health Inform. 2014;5(3):229.

- ↑ West, D. How Mobile devices are Transforming Healthcare.Issues in Technology Innovation 2012; (18): . https://vacloud.us/sandbox/groups/5069/wiki/a69cb/attachments/1ddb8/Brookings%20-%20How%20Mobile%20Devices%20are%20Transforming%20Healthcare.pdf (accessed 25 November 2015).

- ↑ NHS Choices. Tools - Interactive tools, smartphone apps and podcasts. http://www.nhs.uk/tools/pages/toolslibrary.aspx?Tag=&Page=1 (accessed 3 December 2015).

- ↑ NHS Choices. Health Tools: Interactive tools, smartphone apps and podcasts. http://www.nhs.uk/tools/pages/toolslibrary.aspx?Tag=&Page=1 (accessed 25 November 2015).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Scottish Government. A National Telehealth and Telecare Delivery Plan for Scotland to 2015 – Driving Improvement, Integration and Innovation. http://www.gov.scot/resource/0041/00411586.pdf (accessed 25 November 2015).

- ↑ Scottish Centre for Telehealth & Telecare. Supporting Improvement, Integration and Innovation - Business Plan 2012-2015. http://sctt.org.uk/programmes/ (accessed 25 November 2015).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 DiMatteo RM. Variation in Patients’ Adherence to Medical Recommendations: A Quantitative Review of 50 Years of Research. Medical Care 2004; 42: 200-9.

- ↑ Dean SG, Smith, JA, Payne S, Weinman J. Managing time: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of patients’ and physiotherapists’ perceptions of adherence to therapeutic exercise for low back pain. Disability and Rehabilitation 2005; 27: 625-36.

- ↑ Geraghty, M., Glynn, F., Amin, M., Kinsella, J. Patient mobile telephone 'text' reminder: a novel way to reduce non-attendance at the ENT out-patient clinic. Journal of Laryngology & Oncology 2007:122:296-298

- ↑ Monroe, C., Thompson, D., Bassett, D., Fitzhugh, E., Raynor, H. Usability of mobile phones in physical-activity related research: a systematic review. American Journal of Health Education 2015:46:196-206

- ↑ Kirwan M, Duncan, MJ, Vandelanotte C, Mummery, WK. Using Smartphone Technology to monitor physical activity in the 10,000 Steps program: a matched case-control trial. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14: e55.

References[edit | edit source]

.