Wilson's Disease: A Case Study

Original Editor -Yuka Abe,

Top Contributors - Courtney Lim, Jocelyn Chung, Naiya Patel, Sydney Trinh

Abstract[edit | edit source]

This is a fictional case study developed by Queen's University Physical Therapy students for the Queen's Neuromotor Function Project. The purpose of this study is to describe the presentation of Wilson’s Disease in young and recently diagnosed patient, and the significance of physiotherapy on the symptoms and quality of life of the individual.

In this case study, Chris Brown is a 28 year old male presenting with Wilson's Disease. The subjective and objective findings were recorded during his initial assessment. Upon assessment, it was found that he had symptoms including hypertonia and decreased range of motion, leading to problems with walking and participating in his hobbies, thus improving patient features according to the ICF model: body structure and function, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. Outcome measures used to assess the patient were goniometry, the Unified WD Rating Scale (UWDRS), and the TRG Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS). The patient's functional status prior to the diagnosis, the acuity of the condition, and his willingness to participate in meaningful activities are favourable factors for the patient's prognosis, however he is at risk for future falls as he lives on his own. Based on this, patient-centered goals were created, and a physiotherapy intervention plan was developed. The intervention plan included balance training, strengthening and range of motion exercises, and functional capacity training. Compliments to the intervention plan included virtual reality (VR) an innovative technology-mediated tool. Implementing interdisciplinary aspects to treatment, referrals to speech language pathology, occupational therapy, and psychiatry, were made to target issues outside of the physiotherapy scope of practice.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Wilson’s Disease (WD) is a genetic disorder involving an excess of copper in the body, due to the genetic mutation of the ATP7B gene[1][2]. This rare neurological condition commonly affects those between the age of 10-20 years, however those younger than 5 years and older than 70 years are able to be diagnosed as well [3][4]. It predominantly affects the liver and brain, where neurological and hepatic symptoms are said to be equivalent in prevalence among patients, however symptoms differ in severity and characteristics depending on which organ is involved[5]. The range of symptoms makes diagnoses hard for patients with WD, as symptoms can be solely hepatic, neurological or psychological, or a combination of them[6]. Common neurologic symptoms of patients with WD are dysarthria, ataxia, dyskinesia (orofacial), dystonia, Parkinsonism, chorea, and tremors (wing-beating) [6].

The purpose of this case study is to inform readers about the presentation of WD in a previously active and young individual recently diagnosed with this condition. This study also dissects the role of physiotherapy and its effect on moderating symptoms and improving function along with quality of life in the individual with WD. Furthermore, this case study provides the understanding of the significant role of non-physiotherapist members and interdisciplinary teams in the care of individuals with neurological conditions such as WD. Lastly, this case study grants the online translation of knowledge within the scope of physiotherapy, and aids in the understanding of technology in neurological rehabilitation.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Chris Brown is a 28-year-old male, who is an accountant who lives independently in Toronto, Ontario. He works as an accountant in an office downtown. Prior to his diagnosis, his hobbies included golfing on the weekend with friends. The patient was diagnosed with WD 1 month ago and was referred to outpatient rehabilitation physiotherapy by a neurologist. His main complaints involve hypertonic or dyskinetic symptoms when using his face and mouth; and his lack of tolerance for walking or playing golf due to his symptomatic tremors. He has noticed changes in his muscle strength and coordination in his feet when walking.

Subjective Information[edit | edit source]

History of Present Illness

28-year old male was diagnosed with WD 1 month ago by a neurologist based on family history and symptoms relating to the condition. The patient had complained to his family doctor of involuntary movements of his face and tremors in his legs when walking, causing him to frequently lose his balance. The patient has no signs of any contraindicative conditions or past medical procedures, however he presents with a precaution of depression-like symptoms, due to the novelty of WD and its rarity within the population. He had no past experiences with physiotherapy and had been referred to the neurologist by his family doctor. He has recently been prescribed Cuprimine® to manage copper concentrations in his body.

Functional Status

The patient lives independently in a bungalow and requires no gait aid but minimal assistance with ambulation. His circumstance causes him to have an increased time in walking, especially for long periods of time or with elevation, and has difficulty controlling his movements as he experiences many wing-beating tremors, as well as muscle weakness. Relative to his previously active schedule, his physical activity levels have decreased significantly over the past month. He has been allowed accommodations to work from home, as he is unable to commute to work. Additionally he is having tribulations involving participation in recreational sporting activities like golf as it requires muscle strength and control. Eventually, he would like to regain his initial or similar to his initial skill level regarding his golfing.

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

Objective Information[edit | edit source]

There are 3 categorical problems involving this patient and his symptoms.

- Body Structure and Function

- Unable to achieve optimal flexion in the lower extremity, especially dorsiflexion of the ankle

- Dyskinesia, affecting his ability to use his face and mouth muscles voluntarily

- Hypertonia, specifically rigidity, chorea and tremors

- Activity Limitations

- Unable to walk without minimal amount of assistance due to muscle fatigue and lack of balance and coordination

- Participation Restrictions

- Unable to golf with his friends on the weekends due to essential tremors

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Range of Motion as Measured by Goniometry:

| Range of Motion | |

|---|---|

| Ankle Dorsiflexion | 10° |

| Ankle Plantarflexion | 37° |

| Ankle Inversion | 24° |

| Ankle Eversion | 12° |

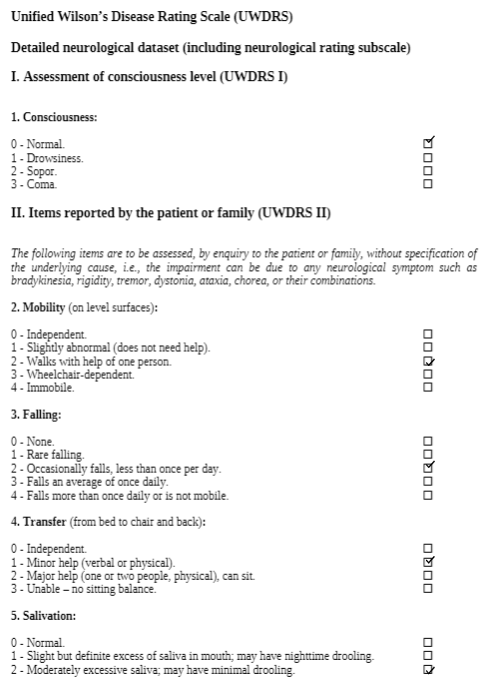

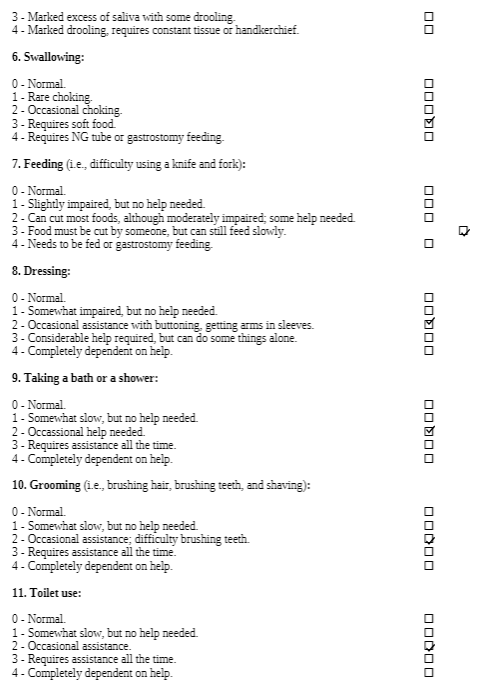

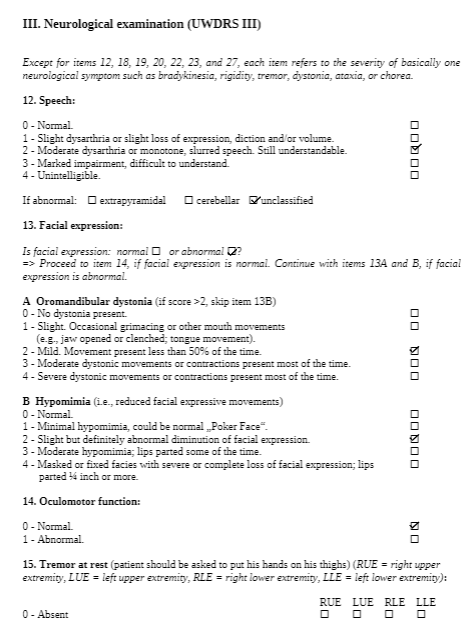

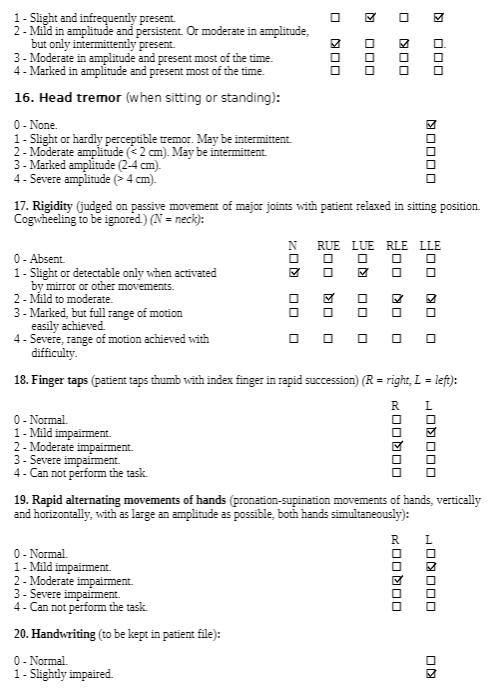

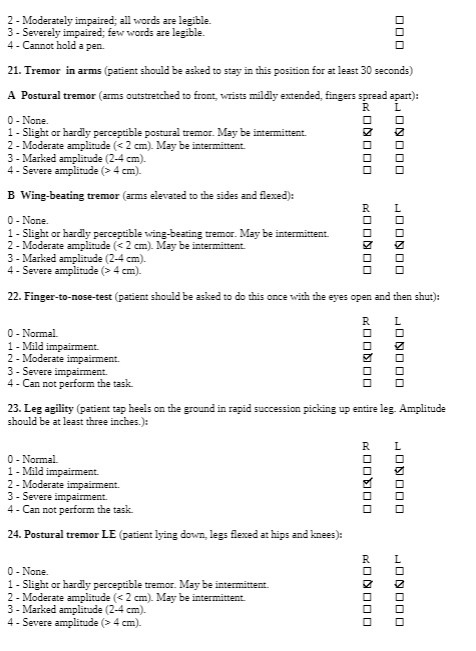

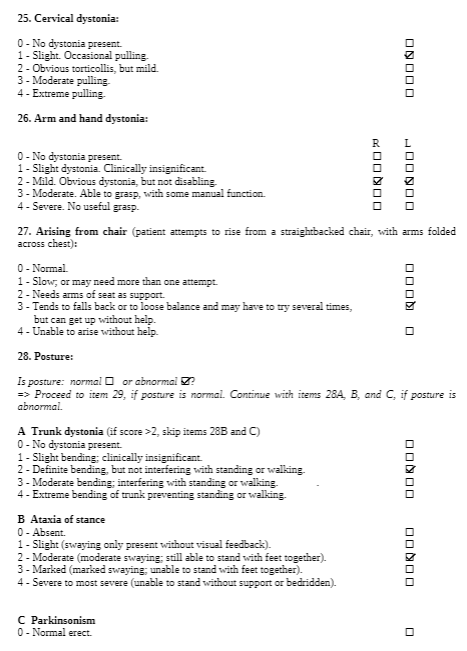

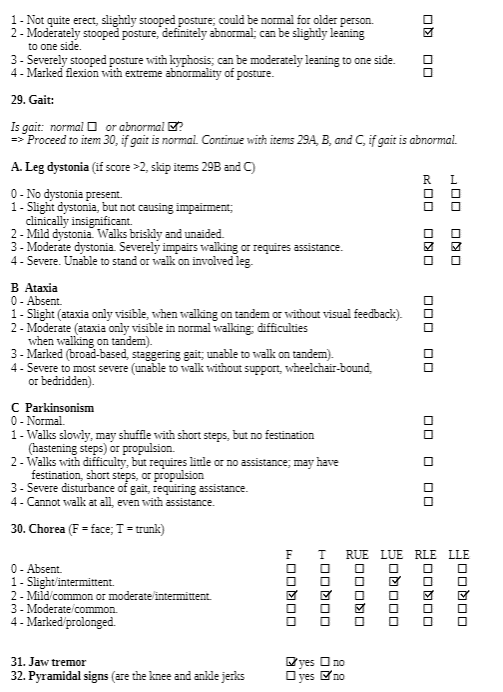

UWDRS Outcome:

UWDRS Score Part I: 0

UWDRS Score Part II: 21

UWDRS Score Part III: 76

2MWT: Unable to complete at this time as patient requires assistance when walking

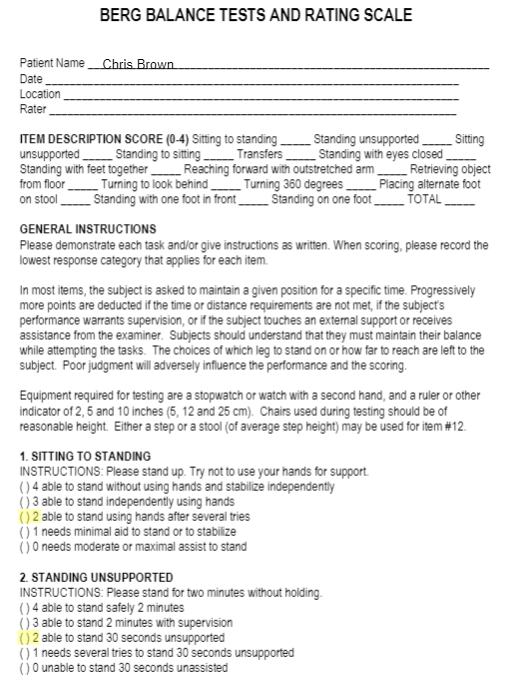

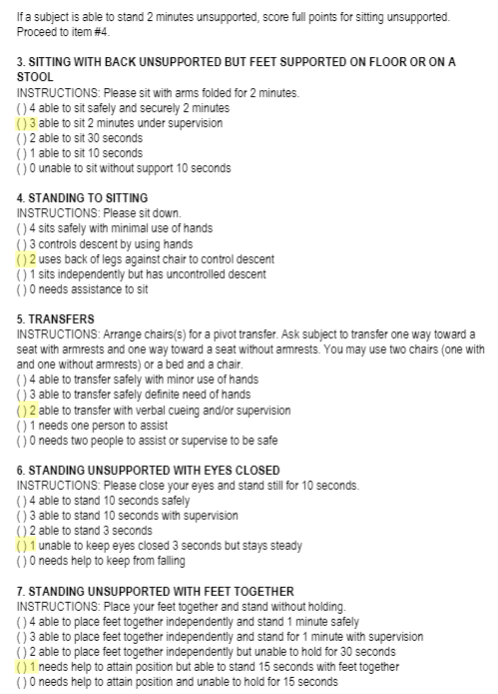

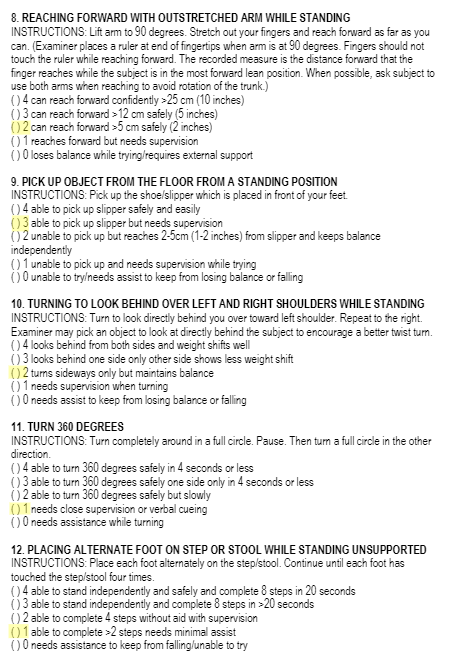

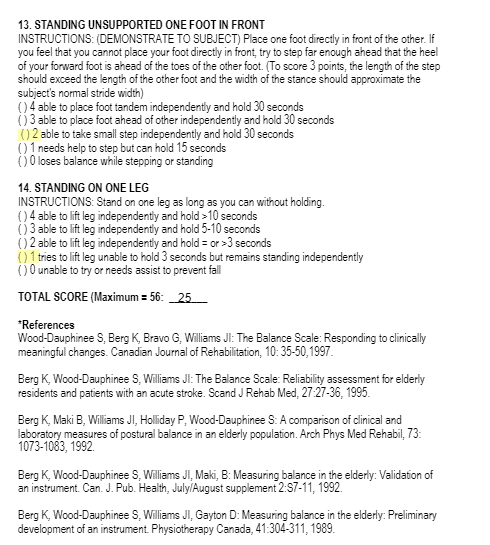

BERG Balance Scale Outcome:

BERG score: 25 → Indicates patient is at high risk of falls

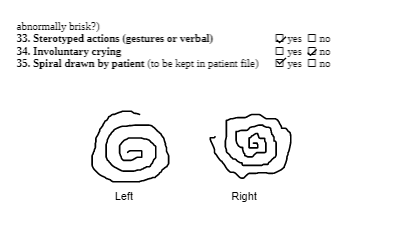

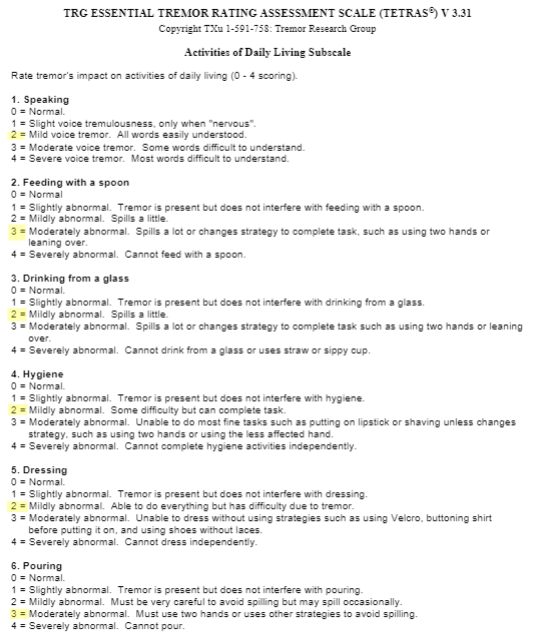

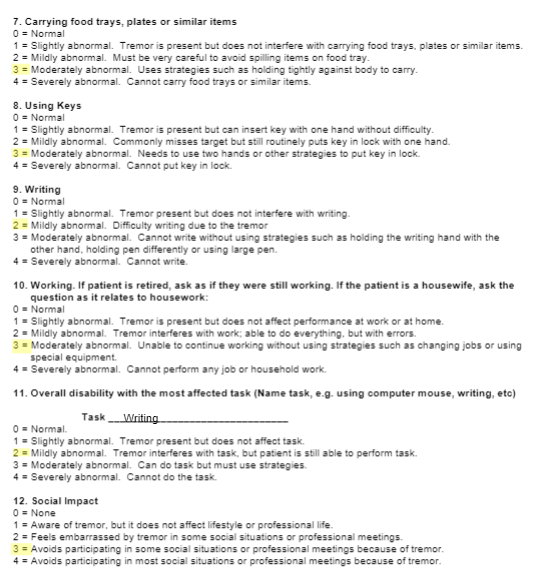

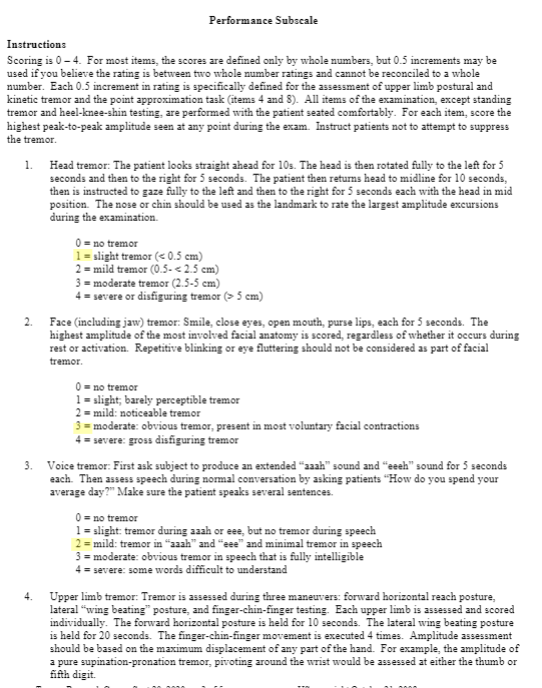

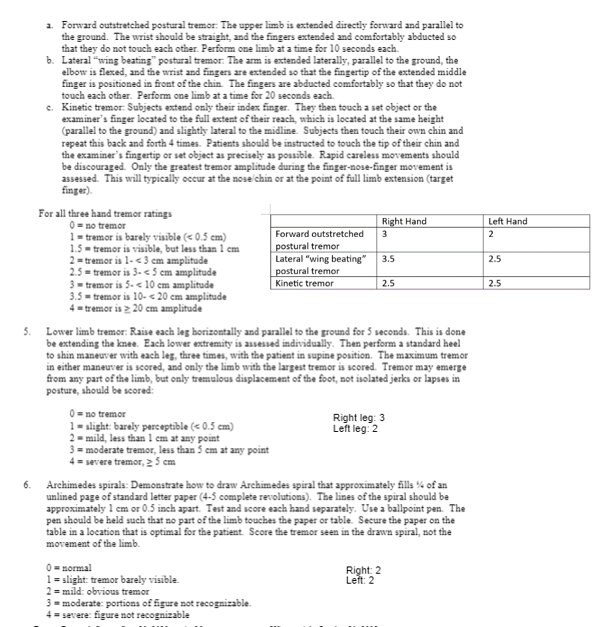

TETRAS Outcome:

TETRAS Score ADLs: 30

TETRAS Score Performance: 39.5

Common Comorbidity to Screen For[edit | edit source]

Psychiatric disorders, specifically depression, is a common comorbidity that should be screened in patients with WD. Evidence shows that there is a higher prevalence of depression in those with WD as compared to those with other chronic diseases that live with a similar level of disability[7]. Psychiatric disorders as a comorbidity have a poorer prognosis as these complicate the course of WD with significant impact on quality of life[8]. Therefore, it is necessary to screen depression in patients with WD. Physiotherapists can use many assessments, such as Beck’s Depression Inventory, a self-reported scale, to which the they can refer to if necessary.

Clinical Hypothesis[edit | edit source]

28 year old male diagnosed 1 month ago with WD presenting with hypertonicity and erratic involuntary movements. Previous function as a golfer and the acuity of the condition (subacute) indicates a promising projection of the patient’s condition and his participation in meaningful activities, but is at risk for future falls as he lives on his own.

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Goals[edit | edit source]

Problem 1: Unable to achieve optimal flexion in the lower extremity, especially dorsiflexion of the ankle

- Short term goal: In 2 weeks, Chris will be able to increase dorsiflexion at the ankle to 15 degrees as measured by goniometry

- Long term goal: Chris will be able to heel strike in his gait cycle without an AFO for discharge

Problem 2: Dyskinesia, affecting his ability to use his face and mouth muscles voluntarily

- Short term goal: In 2 weeks, Chris will have voluntary control of his face muscles as shown by a smile on his face

- Long term goal: Chris will have voluntary control of his mouth muscles as he will be able to chew solid foods for two meals a day for discharge

Problem 3: Hypertonia, specifically rigidity, chorea and tremors

- Short term goal: In 2 weeks, Chris will be able to pick up a glass of water with minimal tremors as measured by minimal spillage of water

- Long term goal: Chris will be able to feed himself independently for discharge

Problem 4: Unable to walk without minimum amount of assistance due to muscle fatigue and lack of balance and coordination

- Short term goal: In 2 weeks, Chris will improve standing balance as measured with improvement on the BERG balance scale

- Long term goal: Chris will be able to walk 30 meters independent with a single point cane for discharge

Problem 5: Unable to golf with his friends on the weekends due to essential tremors

- Short term goal: In 2 weeks, Chris will be able to put a golf ball 1 meter away from the putter

- Long term goal: Chris will be able to perform a golf swing with a golf club for discharge

Discharge date: projected 3 months from admission to outpatient rehabilitation – will be dependent on trajectory of patient progression.

Physiotherapy Intervention Plan[edit | edit source]

Although we cannot cure WD, we can treat the underlying neurological and motor impairments that affect a person’s activities of daily living and their overall quality of life. Through physical therapy interventions, we can treat symptoms such as decreased range of motion, rigidity, tremors, dystonia, dyskinesia, poor balance, and abnormal gait patterns as well as educate the patient on adaptive and energy conservation techniques to improve endurance and activity tolerance. Currently, WD is quite rare and requires further research in rehabilitation therapies. However, because WD has similar symptoms to other neuromotor conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and Stroke, we have implemented transferrable research findings to support our therapeutic interventions.

Frequency: Outpatient rehab 2-3 times per week, and home exercise plan to be completed 3 times per week.[9]

A case report by Maiarú et al. (2016) focused on physical therapy interventions for a 32-year-old male who was diagnosed with WD[9]. The authors describe the use of exercises to improve static and dynamic balance as well as functional capacity, which could be transferrable to our patient case with certain modifications[9]. To address our patient’s goal of improving balance and gait, we can implement both static and dynamic balance exercises. We can begin with static balance by standing on a hard surface with feet together, and progressing to semi-tandem, tandem, and single-leg stance [9]. To further progress and challenge our patient, we can manipulate somatosensory aspects such as eyes open vs closed, making the surface unsteady (foam), or use or perturbations (internal/external). Standing exercises can each be performed for 1-minute durations, in 4 series, with breaks in between or as needed[9].

In terms of motor presentation, WD has some overlapping presentations as Parkinson’s disease, a condition in which there is substantial research on physical therapy. For dynamic balance and gait training, there is research on Parkinson’s disease that indicates treadmill walking as well as dance therapy shows improvements in gait as well as improved scores on Berg Balance scale[10]. Therefore, to improve our patient’s dynamic balance and gait, we can implement combined sessions of treadmill walking on low speeds for 25–30-minutes and dance sessions for 25–30-minutes (or as tolerated), such as tango or large movement dances. These activities can be performed in bouts of 3 minutes with 5-minute breaks or as the patient tolerates, totalling up to 1 hour per session[9]. Ambulation in open environments can also be initiated once our patient has improved dynamic balance, in order to further improve function at home and in the community as our patient enjoys golfing.

A common finding with WD is tremors of the hands which can be very disruptive to daily living and participation in activities. For our patient’s goal of being able to golf we can implement strengthening and range of motion exercises for the upper extremities, with a focus on eccentric exercises for controlling tremors of the hand[11]. Studies suggests that progressive eccentric exercises of the upper extremity can improve resting hand tremors as seen in Parkinson’s disease[11]. Based on this research, we are inferring that this intervention could possibly have similar effects on tremors seen in WD. To add on, the use of Tremor glove stimulation has been supported by research, suggesting it can reduce the angular velocity and peak magnitude of tremors in individuals with Parkinson’s disease[12]. As we know our patient enjoys golfing, which requires dual tasks such as socializing while walking and carrying a golf club or picking up a golf ball. As a result, we can incorporate a combination of motor and cognitive dual task training which studies have found is effective in improving balance and gait in chronic stroke patients when performed together[13]. In this case, we can create a track with various sized balls laid out, allowing the patient to ambulate a few steps then pick up a ball, and adding the cognitive task of counting backwards by 3's from 199 (as an accountant he will enjoy this task as well). We can progress this task by swinging a light golf club while counting backwards by 4's from 399. Since these tasks focus on our patient's hobbies and career, they are more functional and patient specific which can promote participation and motivation.

To improve flexion of the lower extremities, specifically at the ankle, we can implement seated range of motion exercises, focusing on dorsiflexion of the ankles and progressing the exercises by using different TheraBands (increasing resistance). Seated lower extremity exercises can be performed daily for 1-2 sets of 8-10 reps or as tolerated, and can include, ankle plantar flexion/ dorsiflexion, knee extension/ flexion, hip flexion/abduction. To add on, reduced ankle dorsiflexion can be treated using Mulligan’s mobilization with movement technique (MWM). A systemic review of RCTs was conducted by Alamer et al., (2021), that found MWM showed improvements in range of motion, balance, and gait functions among individuals with chronic stroke[14]. Parameters based on this systemic review could generally be grade III mobilization with 3 sets of 10 repetitions of ankle dorsiflexion, 3 times per week[14].

To treat more functional aspects of the patient’s life such as lifting a glass of water or independent feeding, we can implement functional capacity training[9]. Functional capacity training for our patient can include standing at counter and stacking different sized cups, placing cups on a shelf, and picking up cups with water or with weights to imitate the presence of liquids in a cup. This task can be progressed by changing cup sizes and the heaviness of the cup, as well as the height of the counter or shelves to which the patient would reach for. In addition, this task can be performed with minimal hand on hand assistance (active assisted) depending on the extent of the hand tremors during that session, to help initiate and control the desired movement and then progress to independent (active) movement. To add on, the task of feeding can be practiced by sitting at a table and picking up a utensil then repeating the movement pattern of bringing a utensil to the mouth and back to the table. This type of intervention can be dosed based on patient tolerance and be performed in bouts of 3-5 minutes with rests in between, totaling 30 minutes and ending with 15 minutes of stretching the hand/ upper extremity[9].

There is insufficient research on physiotherapy treatment of orofacial dyskinesia in WD, however there is research on facial rehabilitation strategies in patients with facial palsy. Although the conditions are not equivalent, the goal of re-education and control of facial muscles is similar, therefore we could attempt to use similar interventions. As the patient has a goal to voluntarily smile and chew food, our focus is on targeting movement and strength of the orofacial muscles. Research suggests interventions which include the use of soft tissue mobilization to target muscle tightness, neuromuscular retraining/ re-education to help facilitate the return of normal facial movement patterns while decreasing unwanted movements, and self-management strategies so patients can identify, develop, and refine proper facial movement patterns and expressions[15]. Additional studies indicate that orofacial physiotherapy should also include joint mobilization and muscle conditioning[16]. Focusing on strengthening, our patient can perform the following facial exercises daily: puckering the lips, smiling with teeth and gums showing, puffing the cheeks with air, pursed lips, lifting lower lip by pouting, holding a straw or stick between the lips[16]. For the tongue, exercises include sticking the tongue out straight, to the left, to the right, up and down, sweeping the tongue along the teeth and gums, and pushing the tongue against the cheeks[16].

Innovative Technology[edit | edit source]

Virtual reality (VR) is new and upcoming innovative technology that has been shown to help facilitate and improve the rehabilitation process. Virtual reality uses principles of neuroplasticity and motor learning whilst utilizing computer algorithms to make decisions towards progressing the difficulty of a task[17]. It has the ability to track neuroplastic changes and can be used to track recovery[17]. Studies have shown VR to have great ecological validity and researchers have been steadily improving its technology (e.g higher resolution 3D systems are more prevalent)[17]. For instance, new research has worked to improve head mounted displays, allowing these displays to produce realistic, high resolution augmented visual feedback[17]. This visual feedback can help with sensorimotor integration and thus help the patient improve their gait[17]. Our patient, Chris Brown, presents with gait impairments. VR technology can be used to help in the treatment process of our patient’s gait patterning and can help Chris attain his goal of achieving proper heel strike. Another applicable example is that VR can be used to improve upper extremity functioning and fine motor control by providing hepatic feedback to the patient[17]. This can also help to facilitate Chris Brown's rehabilitation process by giving him an alternative method to practice different fine motor movements, such as drinking a glass of water or independent feeding. VR is a fresh new rehabilitation approach that can be engaging for patients and could help with motivation.

Despite the benefits that VR can bring, it does come with a few challenges. Two of the most pressing accessibility issues include expensive equipment costs and safety issues and considerations[18].

To mitigate costs barriers associated with VR systems, facilities/clinicians can work with researchers in pilot programs[18]. This is a great way for the clinician and facilities to see if VR is suitable for their patient population while assessing if VR would be a reasonable investment that ultimately will save money in the long-term[18]. Cost barriers can also be addressed by using alternative materials such as a cardboard headset[18]. Some VR training content could also be used in a more accessible form such as on a desktop or mobile device[18].

To mitigate issues with safety, proper clinician training and education would be appropriate. To use VR, there could be requirements such as completion of a training course or passing a specific exam[18]. The patient also needs to be given proper comprehensive education and informed consent. Side effects of VR can include cybersickness, perceptuomotor after-effects, headaches and eye-strain[18]. The patient is also at risk for addiction to VR-based technologies[18]. The patient should be informed of both benefits and drawbacks of the treatment, as well as alternative solutions. This can help to ensure safety and proper usage of VR systems by both patient and practitioner.

Outcome[edit | edit source]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The Unified Wilson’s Disease Rating Scale (UWDRS) would be appropriate for this patient in measuring the body structure and function limitations. The UWDRS consists of 3 subscales – neurological, hepatic, and psychiatric. The neurological subscale consists of items including rigidity, chorea, tremors, as well as facial expression and oromandibular dystonia. The UWDRS has been shown to be a reliable and valid tool to monitor disease progression in patients with WD [19]. Items on the UWDRS were adapted from scales that have already been established in measuring neurological impairments, including the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), Barthel index, and the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale, which suggests a high degree of content validity[19].

To evaluate the activity limitation, the 2 Minute Walk Test (2MWT) can be used. The 2MWT measures the distance walked in 2 minutes, and can be used to quantify walking limitations and fatigue. This measure has been proven to be reliable and valid in patients with various neuromuscular diseases[20]. In addition, the 2MWT is well correlated with the 6 Minute Walk Test, which is a widely used and validated tool in measuring walking capability. For this case, the patient is currently unable to walk without assistance, so the 2MWT would be administered when the patient is able to walk independently. Standing balance can be assessed using the BERG balance scale, as the patient is able to stand independently. This scale has been validated in various populations, including those with neuromuscular disease, and has been shown to be an effective tool for screening for risk of falls [21]. Furthermore, as mentioned previously, WD has a similar presentation to that of Parkinson's Disease. The BERG balance scale has been shown to be a reliable and valid tool for assessing balance ability in patients with Parkinson's Disease[22], which suggests that this may be a valuable tool for patients with WD as well.

For participation limitations, the Tremor Research Group Essential Tremor Rating Scale (TETRAS) can be used to measure essential tremors. The TETRAS consists of ADL (12 items) and performance (9 items) sections[23]. Each item is scored on a scale of 0 to 4, where a higher score indicates more severe tremors. It is a well-validated and reliable tool to assess the severity of essential tremors, which is commonly present in those with WD[24][25] . Furthermore, the TETRAS assesses wing-beating tremors which is characteristic of WD.

Modifications to Intervention[edit | edit source]

Although intervention plans target current problems and limitations of the patient, we must also consider the possibility of adverse events and ways in which we can modify our plans to best support our patient. A 2022 report on adverse events seen in Parkinsonian patients, indicates that falls are often the number one adverse event reported either during, or after physiotherapy interventions among Parkinson’s patients[26]. As our patient presents with Parkinsonism, they could also be at a higher risk of falls. If our patient were to experience a fall as an adverse event, the time and intensity of the physiotherapy intervention plan could be reduced. For example, we would still want the frequency to be maintained to prevent functional decline, however we can adjust how long we are performing exercises or mobility and how much resistance is applied. The intervention plan can be modified to be performed in sitting until the patient feels comfortable performing exercises in standing. Another modification may have the patient standing so the intervention can be performed in shorter bouts with increased rest periods. To add on, we can incorporate additional rest breaks and build up the patient’s tolerance if they present with a reduced activity tolerance after their fall. In addition, if the patient has weakness or soreness, we can offer modalities such as heat, ice, or rest that can help with any swelling or bruising which may comfort them and keep them motivated to continue therapy. An important factor to consider is also how the patient fell or what the source or trigger was and then to incorporate a plan to prevent the fall from reoccurring in the future. Increasing safety is an effective step as it is our responsibility as physiotherapists to ensure the patient’s safety as well and comfort and tolerance with the interventions.

Referrals[edit | edit source]

3 other healthcare professionals/services that can be involved in the client’s care include:

-speech language pathology

-occupational therapy

-psychiatric care and counselling

Speech language therapy would be the priority recommendation for Chris Brown as they address problems regarding communication, swallowing, and eating[27]. The most pressing issue would be swallowing and eating as these skills are crucial for survival and it is important to know the patient’s functional level to provide adequate support and mitigate risks such as aspiration or choking. The speech language therapist can assess oral muscle functioning and strength for speaking and swallowing[27]. Based off this information, they can make recommendations for an appropriate diet and can create a treatment plan to help improve independence with eating and swallowing[27]. The speech language therapist can also help with verbal and non-verbal communication, recovery of speech, language, and memory skills[27]. These skills are essential for daily living and improving these skills will contribute to an overall improved quality of life and well-being. Working on these skills will be instrumental in success with other therapies (physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychiatric care and counseling).

Discussion[edit | edit source]

WD is a rare condition, with diagnosis typically occurring in younger active individuals. By creating a case study, we hope to put focus on this disease so that our fellow physiotherapist colleagues can identify how impactful this can be to the functions, activities and participation of those who live with this condition. Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model to guide interventions allows interaction to be between us and the person rather than us and the disease. By presenting this information, we would like to incite discussion on how we can provide supportive strategies to lessen the effects of disability on the everyday lives of those with WD.

Multiple Choice Questions[edit | edit source]

What are the most common signs/symptoms of Wilson’s Disease?

A) Dystonia, Orofacial dyskinesia, and Wing-beating tremor

B) Sensory impairment, Aphasia, paraplegia

C) Motor ataxia, facial drooping, stooped posture

D) None of the above

Answer: A

What is the most appropriate and specific outcome measure that assesses neurological, hepatic, and psychiatric function in patients with Wilson’s Disease?

A) Wilson’s Disease Symptom Severity Survey

B) Barthel Index

C) Unified Wilson’s Disease Rating Scale

D) Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale

Answer: C

What is the number one reported adverse event that should be considered when implementing interventions?

A) Postural hypotension

B) Falls

C) Rash

D) Increased Wing-beating tremor

Answer: B

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Bull PC, Thomas GR, Rommens JM, Forbes JR, Cox DW. The Wilson disease gene is a putative copper transporting P–type ATPase similar to the Menkes gene. Nature genetics. 1993 Dec;5(4):327-37.

- ↑ Mulligan, C., & Bronstein, J. M. (2020). Wilson Disease: An Overview and Approach to Management. Neurologic clinics, 38(2), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2020.01.005.

- ↑ Taly AB, Meenakshi-Sundaram S, Sinha S, et al. Wilson disease: Description of 282 patients evaluated over 3 decades. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86(2):112–21.

- ↑ Ala A, Borjigin J, Rochwarger A, et al. Wilson disease in septuagenarian siblings: Raising the bar for diagnosis. Hepatology 2005;41(3):668–70.

- ↑ Hedera P. Update on the clinical management of Wilson’s disease. The application of clinical genetics. 2017;10:9.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Soltanzadeh A, Soltanzadeh P, Nafissi S, et al. Wilson’s disease: A great masquerader. Eur Neurol 2007;57(2):80–5.

- ↑ Ehmann, T.S., Beninger, R.J., Gawel, M.J., & Riopelle, R.J. (1990). Depressive symptoms in Parkinson's disease: A comparison with disabled control subjects. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 3, 3–9. doi:10.1177/ 089198879000300102

- ↑ Carta, M.G., Mura, G., Sorbello, O., Farina, G., & Demelia, L. (2012). Quality of life and psychiatric symptoms in Wilson's Disease: The Relevance of Bipolar Disorders. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8, 102–109

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Maiarú, Ma., Garcete, A., Drault, M., Mendelevich, A., Modica, M., Peralta, F. Physical Therapy in Wilson’s Disease: Case Report. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation - International. 2016; 3:1

- ↑ Boonstra T., Kooij H van der, Munneke M, Bloem B. Gait disorders and balance disturbances in Parkinson’s disease: clinical update and pathophysiology. Current opinion in neurology. 2008;21(4):461–71.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kadkhodaie M, Sharifnezhad A, Ebadi S, Marzban S, Habibi SA, Ghaffari A, et al. Effect of eccentric-based rehabilitation on hand tremor intensity in Parkinson disease. Neurological sciences. 2020;41(3):637–43.

- ↑ Shahien M, Elaraby A, Gamal M, Abdelazim E, Abdelazeem B, Ghaith HS, et al. Physical therapy interventions for the management of hand tremors in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Neurological sciences. 2023;44(2):461–70.

- ↑ An HJ, Kim JI, Kim YR, Lee KB, Kim DJ, Yoo KT, et al. The Effect of Various Dual Task Training Methods with Gait on the Balance and Gait of Patients with Chronic Stroke. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2014;26(8):1287–91.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Alamer A, Melese H, Getie K, Deme S, Tsega M, Ayhualem S, et al. Effect of Ankle Joint Mobilization with Movement on Range of Motion, Balance and Gait Function in Chronic Stroke Survivors: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Degenerative neurological and neuromuscular disease. 2021;11:51–60.

- ↑ Robinson MW, Baiungo J. Facial Rehabilitation: Evaluation and Treatment Strategies for the Patient with Facial Palsy. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2018;51(6):1151–67.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Sodhi A, Nair P, Hegde S. Physiotherapy: Key to the kinetics of orofacial musculature. Journal of Indian Academy of Oral Medicine and Radiology. 2014;26(4):419–24.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Weiss, P. (Tamar) L., Keshner, E. A., & Levin, M. F. (2014). Virtual Reality for Physical and Motor Rehabilitation. Springer New York, 222-225.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Baniasadi, T., Ayyoubzadeh, S. M., & Mohammadzadeh, N. (2020). Challenges and Practical Considerations in Applying Virtual Reality in Medical Education and Treatment. Oman medical journal, 35(3), e125. https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2020.43

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Leinweber, B., Möller, J. C., Scherag, A., Reuner, U., Günther, P., Lang, C. J. G., Schmidt, H. H. J., Schrader, C., Bandmann, O., Czlonkowska, A., Oertel, W. H., & Hefter, H. (2008). Evaluation of the Unified Wilson’s Disease Rating Scale (UWDRS) in German patients with treated Wilson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 23(1), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21761

- ↑ Andersen, L. K., Knak, K. L., Witting, N., & Vissing, J. (2016). Two- and 6-minute walk tests assess walking capability equally in neuromuscular diseases. Neurology, 86(5), 442–445. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002332

- ↑ Park, S.-H., & Lee, Y.-S. (2017). The Diagnostic Accuracy of the Berg Balance Scale in Predicting Falls. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 39(11), 1502–1525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916670894

- ↑ Berardi, A., Galeoto, G., Valente, D., Conte, A., Fabbrini, G., & Tofani, M. (2020). Validity and reliability of the 12-item Berg Balance Scale in an Italian population with Parkinson’s disease: A cross sectional study. Arquivos De Neuro-Psiquiatria, 78(7), 419–423. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282X20200030

- ↑ Elble, R. J. (2016). The Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale. Journal of Neurology & Neuromedicine, 1(4). https://www.jneurology.com/articles/the-essential-tremor-rating-assessment-scale.html

- ↑ Ondo, W., Hashem, V., LeWitt, P. A., Pahwa, R., Shih, L., Tarsy, D., Zesiewicz, T., & Elble, R. (2018). Comparison of the Fahn-Tolosa-Marin Clinical Rating Scale and the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice, 5(1), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.12560

- ↑ Ortiz, J. F., Morillo Cox, Á., Tambo, W., Eskander, N., Wirth, M., Valdez, M., & Niño, M. (n.d.). Neurological Manifestations of Wilson’s Disease: Pathophysiology and Localization of Each Component. Cureus, 12(11), e11509. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.11509

- ↑ Caniça V, Bouça‐Machado R, Rosa MM, Ferreira JJ, Guerreiro D, Nunes R, et al. Adverse Events of Physiotherapy Interventions in Parkinsonian Patients. Movement disorders clinical practice (Hoboken, NJ). 2022;9(6):744–50.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Other therapies. Wilson Disease Association. (2022, February 21). https://wilsondisease.org/medical-professionals/other-therapies/