The Stress Response Following Serious Injury or Illness: A Biopsychosocial Approach

Top Contributors - Pete Woollhead, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson and Aminat Abolade

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Acute stress can occur in up to 45% of injury survivors following a traumatic injury or illness. It involves an anxiety response that includes re-experience of the traumatic event, intrusive memories, dreams, and strong emotional distress on exposure to triggering events.[1]

Physiotherapists can have a significant role in identifying and early management of patients who present with a stress response following serious injury/illness. Physiotherapists are not typically associated with mental health interventions, but they can have a large impact on the mental well-being of patients.

Traumatic injury is responsible for 11% of global mortality and contributes to a significant amount of physical and psychological morbidity for all age groups[2]. Patients with traumatic injury report a substantial reduction in health-related quality of life compared to other patients, including long-term psychological and physical disability. There is a known associations between injury, depression, anxiety, ASD and PTSD[3].

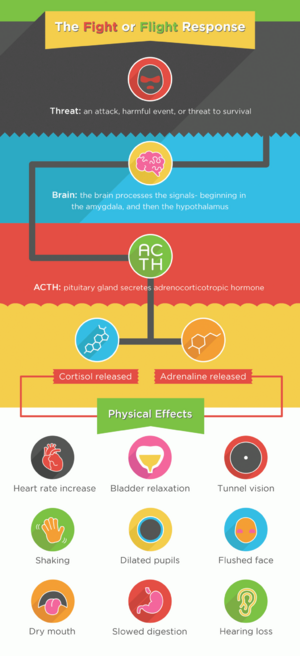

A traumatic experience triggers the stress response ie the hormonal and metabolic changes in the body following physical or emotional trauma or critical illness that cause disequilibrium and threaten homeostasis.[4][5] See Stress and Health

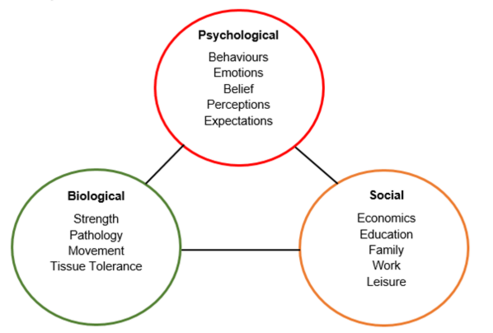

Biopsychosocial Model[edit | edit source]

The biopsychosocial model underpins physiotherapy assessments and interventions. It interconnects physiology, psychology and socio-environmental factors associated to an injury or illness and has been well established within physiotherapy for the past 25 years. It ensures physiotherapists assess and treat a patient holistically and apply intervention to help manage both physical and mental concerns.

Factors Influencing Stress Response[edit | edit source]

Internal Factors[edit | edit source]

Memories of traumatic injury or critical illness can remain prominent for patients and induce frightening recollections, nightmares and delusions.[6] Altered mental status is common in the ICU (see ICU Delirium)), and often worsened by sedation.[7] Other traumatic stressors related to the in-hospital care received include longer ICU length of stay, longer hospital stay, intubation and length of mechanical ventilation[7].

Inability to perform everyday tasks, particularly relating to washing and toileting, may lead to frustration and embarrassment.

People with physical disabilities are at a higher risk of developing psychiatric and substance disorders.[8]

Patients of serious injury or illness often experience pain as a result of the injury or illness and its management[9]. Chronic pain is often comorbid with psychiatric disorders, eg depression[10]. Epidemiological and functional imaging studies suggest that a bidirectional relationship exists between chronic pain and mental health concerns, suggesting that not only does pain induce stress and problems with mental health, but poor mental status may influence pain[9].

External Factors[edit | edit source]

Acute bouts of stress and anxiety affect one’s mental health following severe illness/injury. These conditions were commonly identified at 1 month post injury/illness, and although their prevalence decreased over time, their incidence still remains high at 12 months.[11]

Following severe illness/trauma the combination of several external factors such as a lack of family and social support, financial and/or insurance issues, or contextual conditions (such as deployment and subsequent return home in military personnel) can lead to anxiety and depression, and impact on physical function, pain, and often affecting one’s return to work.

Family and social support play a key role in the recovery of mental health following severe injury. Family support In particular is of great importance since they provide a large portion of the care: they may offer transportation, finances, leisure, and emotional support.[12] Moreover, they are often involved in the rehabilitation goal planning, which may be adapted based on the resources available at their own home. Family stress and unhealthy family communication were found to impair the rehabilitation process.[13]

Insurance and compensation-seeking behaviour have also been shown to impact on psychological well-being. Previous studies showed longer lasting symptoms for compensation seekers or litigants, and can cause delayed work return as well as increased levels of psychological stress secondary to the unresolved financial issues, the injury, or a combination of both factors.[13]

Contextual factors can affect one’s psychological well-being following a road traffic accidents (RTA). Being involved in an RTA can be both stressful and psychologically traumatic, and it has been reported that many individuals involved in RTA’s do not have their psychological reactions attended. This has been suggested to trigger a psychological stress response when these individuals are exposure to environments associated with the traumatic memory.[14]

Flags During Assessment[edit | edit source]

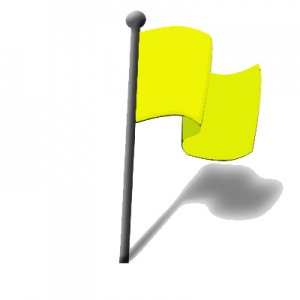

During a physiotherapy assessment, the flag system can be useful to identify any signs or symptoms that may require further attention and investigation. psycho-social flags allow physiotherapists to assess a patient holistically using a bio-psycho-social model, and direct treatment towards the needs of the patient.

- Orange Flags: represent the equivalent of red flags for mental health and psychological problems[15]

- Yellow Flags: identify concerning thoughts, feelings and behaviours linked to the stress of their recovery, change in lifestyle, and social context which may influence a patient’s state of mental health. These include any unusual emotional responses such as increased worry, fear and anxiety, or unusual pain behaviours such as poor coping strategies, avoidance behaviours and over-reliance of passive treatments such as medications. These will be particularly important to monitor if a patient has had an injury/illness that is life changing.

The Role of the Physiotherapist[edit | edit source]

The link between physical health and mental health is widely accepted. Physiotherapy is considered to be integral to the treatment of the physical aspects of musculoskeletal, cardio-respiratory, and neurological conditions, and it plays a significant role in managing chronic pain and preventable diseases.[16] When patients have no co-morbid mental health issues physiotherapists should provide reassurance, psychological support, and education to reduce distress and promote behavioural change.[17]

Any treatment regime needs to take a holistic approach to both the physical injury itself and the adversity induced by it. Recovery from injury, illness, surgery or any life stress requires two key factors:

1.Diagnosis and Targeted Effective Treatment for the Cause of the Problem: Targeted treatment comprises of either a specific exercise program for functional purpose or surgery followed by rehabilitation. Simple, classical medical intervention is based on reductionism (knowing which structure is faulty and fixing it). This is a proven method and is ideal, however, there is often no clear diagnosis, or treatment is not as effective as intended. These and other factors can create barriers to recovery.

2. Identify and Minimise Barriers to Treatment and Addressing Psycho-Social Factors and What to Do with Them: Physiotherapists should look at the whole person, their circumstances and how they react to the stimulus or threat associated with their injury. These factors have the biggest influence on recovery from injury but are almost completely neglected in modern medicine. All good clinicians are aware of how these barriers can negatively affect recovery outcomes, and how much of a challenge it can be to change them. Managing your internal and external environment requires a lot more time and effort because some barriers to recovery are related to long held beliefs and behaviours that are engrained into our daily lives. Changing these can require a big effort for some patients, but can result in positive and long-term change.

To gain the best possible outcome from any adversity or stress, both systems need to be engaged. Rehabilitation is not a procedure or medication, it is a process with many layers and stages, and there are a number of things that can positively or negatively influence a patient’s outcome.[18] During an assessment it is possible for the physiotherapist to identify any yellow or orange flags that may suggest that the patient has any psycho-social or mental health concerns caused by their illness or injury. If not properly addressed during treatment, these stressors and concerns can develop into a more serious mental health condition for the patient. Physiotherapists regularly come into contact with people with common stressors regardless of the setting and it is likely that this will influence engagement and response to treatment. These patients access mainstream physiotherapy and some may need reasonable adjustments. In almost all cases these stressors will not affect the ability to treat in a department.[19]

See Effects of Exercise on Stress management

Psychological goals of physiotherapy

- Raising self-esteem and confidence

- Improving mood and promoting well-being through a structured exercise program

- Motivation for self-management

- Promotion of a more positive body image

- Reducing social isolation

- Improving quality of life

Physical goals

Remain similar to those in every treatment:

- To provide non-pharmacological treatment for pain

- To improve muscle strength and flexibility

- To improve cardiovascular endurance

- Prevention of falls and other mobility issues

- Advice on weight management. [20]

Things to consider during appointments with patients who present with psycho-social concerns as a result of serious injury/illness:

- If the person has any specific likes or dislikes which may affect the appointment, in particular fears

- The impact of their mental health on day to day life and function

- How you will communicate, use words they may be familiar with be respectful, do not stigmatise and remember people with a diagnosis of mental illness are people just like everyone else, communication is key

- Try and understand the wider implication of the injury and use a holistic approach

- You may need to develop your therapeutic relationship before proceeding with a manual assessment or intervention[19]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Bryant, B., & Knights, K. (2011). Pharmacology for Health Professionals. (Vol. 3): Elsevier.

- ↑ Organisation, W. H. (2010). World Health Organisation (WHO)

- ↑ Wiseman, T., Foster, K., & Curtis, K. (2013). Mental health following traumatic physical injury: an integrative literature review. Injury, 44(11), 1383–1390

- ↑ Desborough, J. P. (2000). The stress response to trauma and surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 85(1), 109-117.

- ↑ Correia, M. I. T. D., & De Almeida, C. T. (2005). Nutritional Support for the Critically Ill Patient: A Guide to Practice (2 ed.): CRC Press.

- ↑ Ringdal, M., Plos, K., & Bergbom, I. (2008). Memories of being injured and patients' care trajectory after physical trauma. BMC nursing, 7(8), 1-12.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Jackson, J. C., Hart, R. P., Gordon, S. M., Hopkins, R. O., Girard, T. D., & Ely, E. (2007). Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress symptoms following critical illness in medical intensive care unit patients: assessing the magnitude of the problem. Critical Care, 11(1), R27.

- ↑ Turner, R. J., Lloyd, D. A., & Taylor, J. (2006). Physical disability and mental health: An epidemiology of psychiatric and substance disorders. Rehabilitation Psychology, 51(3), 214-223.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Hooten, W. M. (2016). Chronic pain and mental health disorders: shared neural mechanisms, epidemiology, and treatment. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 91(7), 955-970.

- ↑ Gureje, O., Von Korff, M., Kola, L., Demyttenaere, K., He, Y., Posada-Villa, J., . . . Iwata, N. (2008). The relation between multiple pains and mental disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Pain, 135(1-2), 82-91.

- ↑ Kellezi B, Coupland C, Morriss R, Beckett K, Joseph S, Barnes J, Christie N, Sleney J, Kendrick D. The impact of psychological factors on recovery from injury: a multicentre cohort study. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2017 Jul 1;52(7):855-66.

- ↑ Kellezi B, Coupland C, Morriss R, Beckett K, Joseph S, Barnes J, Christie N, Sleney J, Kendrick D. The impact of psychological factors on recovery from injury: a multicentre cohort study. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2017 Jul 1;52(7):855-66.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Shoulson I, Wilhelm EE, Koehler R, editors. Cognitive rehabilitation therapy for traumatic brain injury: evaluating the evidence. National Academies Press; 2012 Jan 28.

- ↑ Smith B, Mackenzie-Ross S, Scragg P. Prevalence of poor psychological morbidity following a minor road traffic accident (RTA): The clinical implications of a prospective longitudinal study. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2007 Jun 1;20(2):149-55.

- ↑ Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care, 41(11), 1284-1292.

- ↑ Connaughton, J., & Gibson, W. (2016). Do Physiotherapists Have the Skill to Engage in the "Psychological" in the Bio-Psychosocial Approach? Physiotherapy Canada, 68(4), 377–382

- ↑ MacNeela, P., Scott, P. A., Treacy, M., Hyde, A., & O'Mahony, R. (2012). A risk to himself: Attitudes toward psychiatric patients and choice of psychosocial strategies among nurses in medical–surgical units. Research in nursing & health, 35(2), 200-213.

- ↑ Physiosouth. (2019). Successful Rehabilitation: A Patients Guide. Retrieved from https://www.physiosouth.co.nz/articles-and-education/successful-rehabilitation/ [Accessed 14 November 2019]

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 So your next patient has a mental health condition - a guide for physiotherapists not specialising in mental health. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy,(2018) Retrieved from https://www.csp.org.uk/publications/so-your-next-patient-has-mental-health-condition-guide-physiotherapists-not [Accessed 14 November 2019]

- ↑ Kaur, J., Masaun, M., & Bhatia, M. S. (2013). Role of Physiotherapy in Mental Health Disorders. Dehli Psychiatry Journal, 16(2), 404-408.