The Role of Rehabilitation Professionals in Mental Health Disorders Following Stroke

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson and Matt Huey

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation professionals are well educated on stroke impairments such as sensory and motor deficits, impaired balance, gait dysfunction, decreased independence with activities of daily living (ADLs), and changes in language ability and cognition. Mental health disorders are also common following stroke. Recent evidence has shown that mental health disorders following stroke are associated with decreased functional outcomes and lowered quality of life. However, they continue to be under-diagnosed and under-treated. With the exception of poststroke depression, other mental health disorders lack reliable and high-quality evidence for clinical practice. Further research is needed to develop protocols or guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of mental health disorders following stroke.[1]

This article outlines the risk factors of mental health disorders following stroke, discusses assessment steps and tools for mental health disorders, and gives a basic overview of interventions from a multidisciplinary team perspective.

To learn more about specific mental health diagnoses commonly associated with stroke, please read Mental Health Disorders Following Stroke.

Risk Factors of Mental Health Disorders Following Stroke[edit | edit source]

Mental health conditions following stroke are increasingly recognised by the medical community. Currently, most of the research has focused on specific concerns such as (1) depression, (2) dementia, (3) anxiety, and (4) suicide. Other mental health conditions, such as substance abuse disorders, have less evidence-based support.[2]

Due to the time-intensive nature of rehabilitation assessments, treatments, and interventions, rehabilitation professionals are well-placed to aid in screening and preventive education of stroke survivors.

Common risk factors for mental health disorders following stroke include:

- Female biological sex[3]

- Age: <70 years for poststroke depression (PSD),[3] younger populations for poststroke anxiety (PSA) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)[4]

- Previous history of mental health issues[3]

- Family history of mental illness[3]

- Neuroticism[3] ("broad personality trait dimension representing the degree to which a person experiences the world as distressing, threatening, and unsafe"[5])

- Severity of stroke[3]

- Location of the stroke

- The resulting level of disability following stroke[3]

- Level of independence following stroke[3]

- Previous history of smoking[6]

- Lower socioeconomic status[6]

- Decreased social support[3]

- Decreased level of education[3][6]

A 2017 meta-analysis by Shi et al.[3] found that having a predisposing illness, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, and myocardial infarction, was not associated with a diagnosis of PSD.

Screening[edit | edit source]

The American Stroke Association's 2019 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke recommend screening for PSD in the acute phase of stroke recovery, starting two weeks post-stroke.[7] Further research is needed to determine the optimal timing, setting, and follow-up for screening.[8] While PSD is a major focus of recent research, this statement can be generalised to include other, less studied mental health disorders which are known to occur after stroke.

Please see below for more information on recommended screening tools.

Prevention[edit | edit source]

An important component of prevention is to identify those patients at greatest risk and any potential modifiable risk factors. Rehabilitation professionals should use their clinical assessment skills and referral network to identify, diagnose, and appropriately manage mental health symptoms.[9]

Interventions to improve mental health following stroke include:[9]

- Psychosocial interventions: art therapy, music therapy, mindfulness, motivational interviewing, problem solving therapy

- Physical exercise

- Lifestyle medication interventions: yoga, tai chi, pilates, Feldenkrais method, qigong, acupuncture, nutritional care

- Pharmacological interventions

Stroke can also lead some to suicide ideation, attempts, and completion. A 2021 meta-analysis found the risk of suicide in stroke survivors to be nearly twice that of the general population.[10] It is important for rehabilitation professionals to be aware of the risk factors for suicide, refer patients for the treatment of mood disorders, and provide education on limiting access to the means of self-harm as able.[9]

Risk factors for suicide ideation following stroke include:[10]

- Severe acute disability post-stroke

- Longer hospital stay post-stroke

- Ischaemic stroke survivors

- History of depression

- History of hypertension

Special Topic: Stroke Rehabilitation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries[edit | edit source]

Approximately 70 percent of strokes occur in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs). These countries also have a greater disease burden than high-income countries, with most of the stroke speciality resources centralised in urban areas. A 2019 scoping review found that most LMIC are "acute care oriented, urban located, and ill prepared to provide even essential stroke care with access to rehabilitation."[11]

Researchers are attempting to find solutions to known barriers to stroke care services (e.g. lack of human resources, infrastructure, financial support, clinical guidelines, and national policy to support provisions). Many proposals point to the use of digital health strategies, such as telemedicine, tablet-based risk assessment tools, mobile-phone apps for physicians, and text messaging interventions, to fill in the gaps of services stemming from geographic access and provider availability.[11][12]

Consider this information as you continue reading. How could telemedicine be used to address the mental health care needs of patients following stroke in LMICs?

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Below is a list of assessment components which can easily be added to a rehabilitation evaluation or assessment to capture information regarding a patient's risk of mental health disorders.[4]

History of present illness:

- Screen for possible psychological symptoms in the acute phase post-stroke

- History of onset of symptoms

- psychological symptoms

- somatic symptoms (anxiety)

- Detailed history of stroke

Past medical history:

- Age

- Sex

- Previous episodes of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

- Previous history of any psychological disorder (e.g. depression, anxiety, etc)

- Medication and treatment outcomes of past medical conditions

- Family history of mental health disorders

Social and vocational history:

- Personal and social support

- Family income/insurance

Formal Assessment Tools/Scales[edit | edit source]

Clinical Assessment Tools by Topic[edit | edit source]

Behavioural Assessments

- Worker Role Interview (WRI)

- Work Environment Impact Scale (WEIS)

- Bay Area Functional Performance Evaluation (BaFPE)

- Assessment of Occupational Functioning (AOF)

- Kawa Model

The following optional 4-minute video provides a general overview of the Kawa Model from an occupational therapy perspective.

Motor Function Assessment

- National Institute of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale (app version) (PDF version)

- Barthel Index (BI) (app version, modified Barthel Index) (PDF version)

- Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) (app version) (PDF version)

Orientation and Alertness Assessment

Pre-morbid Intellectual Functioning Assessment

Rehabilitation Experience

Vocational Assessments

Assessment Tools for Specific Mental Health Diagnoses[edit | edit source]

Assessment Scales for Depression

- Montogometry-Asberg's Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

- Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

- Becks Depression Inventory (BDI-II)

Assessment Scales for Anxiety

Assessment Scales for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5)

- Impact of Event Scale - revised (IES-R)

- Post-Traumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS-5)

- Acute Stress Disorder Scale (ASDS)

Management and Interventions[edit | edit source]

Managing mental health issues following stroke involves a diverse team of rehabilitation professionals. All team members need to have strong and reliable referral networks to quickly assess and properly treat a patient with mental health care needs.

MDT Role in Management

| MDT Member | Scope of practice | Role in mental health care |

|---|---|---|

| Case Management |

|

|

| Clinical Psychologist and/or

Neuropsychology |

|

|

| Nursing | Within the scope of practice as a nurse, mental health nursing:

|

According to the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, nurses:

|

| Occupational Therapy |

|

|

| Physiotherapy |

|

|

| Speech Language Pathology/Therapy |

|

|

| Spiritual Care |

|

|

Stepped Care Model[edit | edit source]

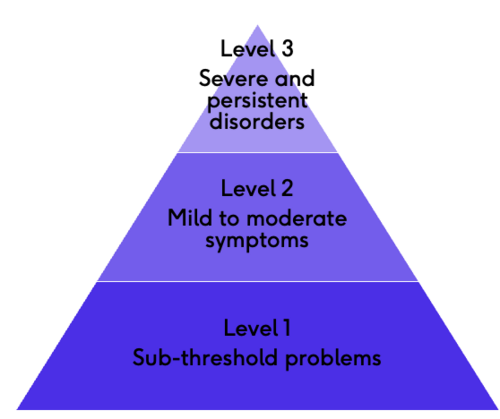

"Stepped care aims to offer patients psychological care in a hierarchical approach, offering simpler interventions first and progressing on to more complex interventions if required. However, not all patients will progress through the system in a sequential manner. Over the course of their recovery, patients may move in and out of this system several times and at different levels. This approach makes best use of skills of the multi disciplinary team and utilises more specialist staff for the patients with complex problems that require this level of help."[21] -NHS Improvement | Stroke

- Initiates care with less intensive treatments (e.g. telemedicine, bibliotherapy, group therapy), then progresses to more intensive treatments involving specialised individual therapy and pharmacological treatment

- As a healthcare delivery method, Stepped Care has two defining core features, least restrictive and self-correcting

- “Least restrictive refers to a low-intensity, cost effective, and least time consuming feature of this method and is used as the first-line treatment."

- “Self-correcting refers to the 'stepping-up' criteria that are utilized in possible preparation of more intensive and expensive treatment, and this is necessary based on treatment outcome."

- Patients are continuously monitored and reassessed. If they are not responding to treatments at their current step, they are referred to the next step of more intensive therapy options

- Case management or nursing can be assigned to coordinate the treatment programme, monitor for progress, and assist with care planning

- An advantage of the stepped care model is that it maximises treatment effectiveness and efficiency while optimising resource utilisation

- The stepped care model has been evaluated and implemented in the treatment of (1) eating disorders, (2) depression, (3) anxiety, (4) obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), (5) PTSD, (6) chronic fatigue syndrome, (7) nicotine dependence, and (8) alcohol use disorders[22]

Interventions[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

CBT is a form of psychological treatment which places an emphasis on helping patients learn to "be their own therapist" by developing coping strategies and changing their frame of thinking. According to the American Psychological Association, CBT involves the following core principles:

- "Psychological problems are based, in part, on faulty or unhelpful ways of thinking.

- Psychological problems are based, in part, on learned patterns of unhelpful behavior.

- People suffering from psychological problems can learn better ways of coping with them, thereby relieving their symptoms and becoming more effective in their lives."[23]

Trained psychologists and the patient work together to gain an understanding of the patient's current frame of thinking and collaboratively develop treatment strategies.[23]

If you want to learn more about how CBT can be adapted for patients following stroke, please read this article.

Exposure and Response Prevention Therapy (ERP)

ERP is a type of CBT specially designed for the treatment of OCD. According to the International OCD Foundation, "The exposure component of ERP refers to practicing confronting the thoughts, images, objects, and situations that make you anxious and/or provoke your obsessions. The response prevention part of ERP refers to making a choice not to do a compulsive behavior once the anxiety or obsessions have been 'triggered'."[24]

Like traditional CBT, a specially trained psychologist works with the patient to gain insight into their triggers and collaboratively create a treatment plan.[24]

Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

According to the International Society of Interpersonal Psychotherapy, IPT is a "time-limited, diagnosis-targeted, well studied, manualized treatment for major depression and other psychiatric disorders".[25]

This treatment approach involves specially trained therapists working with patients to understand that their emotions are "social signals" and how to use this knowledge to improve interpersonal situations and empower social supports.[25]

Behavioural Activation Therapy

Behavioural Activation Therapy encourages the patient to engage in meaningful activities. The goal is to change the way the patient interacts with their environment to improve their outlook and develop a positive mental state. The therapist assists the patient by scheduling activities and monitoring the patient's behaviours. Behavioral Activation Therapy is a flexible form of therapy that can be undertaken in-person, over the phone, or online, and usually over multiple sessions.[26]

Psychomotor or Psychodynamic Therapy

The main goal of Psychomotor Therapy is to demonstrate how goal-directed movement situations can bring about a "positive psychological effect, not only physical skills but also cognitive, perceptual, affective and behaviour." The physical moving of the patient's body is the cornerstone of the psychomotor approach.[27]

For optional additional reading, please see Psychomotor Physical Therapy.

Other forms of psychological interventions include: couples therapy, counselling services, group therapy, and medications or pharmacological interventions such as antidepressants. Treatment interventions can also be a collaboration or combination of any of the above interventions.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clinical Resources[edit | edit source]

- Psychological Care After Stroke (National Health Services)

Optional Additional Reading[edit | edit source]

- Frank D, Gruenbaum BF, Zlotnik A, Semyonov M, Frenkel A, Boyko M. Pathophysiology and current drug treatments for post-stroke depression: A review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022 Dec 1;23(23):15114.

- Mughal S, Salmon A, Churchill A, Tee K, Jaouich A, Shah J. Guiding Principles for Implementing Stepped Care in Mental Health: Alignment on the Bigger Picture. Community Mental Health Journal. 2023 Apr 1:1-8.

- Tjokrowijoto P, Stolwyk RJ, Ung D, Kneebone I, Kilkenny MF, Kim J, Olaiya MT, Dalli LL, Cadilhac DA, Nelson MR, Lannin NA. Receipt of Mental Health Treatment in People Living With Stroke: Associated Factors and Long-Term Outcomes. Stroke. 2023 Jun;54(6):1519-27.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Zhang S, Xu M, Liu ZJ, Feng J, Ma Y. Neuropsychiatric issues after stroke: Clinical significance and therapeutic implications. World journal of psychiatry. 2020 Jun 6;10(6):125.

- ↑ Skajaa N, Adelborg K, Horváth-Puhó E, Rothman KJ, Henderson VW, Thygesen LC, Sørensen HT. Stroke and risk of mental disorders compared with matched general population and myocardial infarction comparators. Stroke. 2022 Jul;53(7):2287-98.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Shi Y, Yang D, Zeng Y, Wu W. Risk factors for post-stroke depression: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2017 Jul 11;9:218.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Banerjee, S. Stroke. The Role of Rehabilitation Professionals in Mental Health Disorders Following Stroke. Physioplus. 2023.

- ↑ Britannica. neuroticism. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/science/neuroticism (accessed 17/July/2023).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Khedr EM, Abdelrahman AA, Desoky T, Zaki AF, Gamea A. Post-stroke depression: frequency, risk factors, and impact on quality of life among 103 stroke patients—hospital-based study. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery. 2020 Dec;56:1-8.

- ↑ American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. 4.10. Depression Screening. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/STR.0000000000000211 (accessed 17/July/2023).

- ↑ Towfighi A, Ovbiagele B, El Husseini N, Hackett ML, Jorge RE, Kissela BM, Mitchell PH, Skolarus LE, Whooley MA, Williams LS. Poststroke depression: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2017 Feb;48(2):e30-43.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Chun HY, Ford A, Kutlubaev MA, Almeida OP, Mead GE. Depression, anxiety, and suicide after stroke: a narrative review of the best available evidence. Stroke. 2022 Apr;53(4):1402-10.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Selvaraj S, Aggarwal S, de Dios C, De Figueiredo JM, Sharrief AZ, Beauchamp J, Savitz SI. Predictors of suicidal ideation among acute stroke survivors. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2022 Dec 1;10:100410.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Prvu Bettger J, Liu C, Gandhi DB, Sylaja PN, Jayaram N, Pandian JD. Emerging areas of stroke rehabilitation research in low-and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Stroke. 2019 Nov;50(11):3307-13.

- ↑ Yan LL, Li C, Chen J, Miranda JJ, Luo R, Bettger J, Zhu Y, Feigin V, O'Donnell M, Zhao D, Wu Y. Prevention, management, and rehabilitation of stroke in low-and middle-income countries. Eneurologicalsci. 2016 Mar 1;2:21-30.

- ↑ YouTube. The Kawa Model | InfOT. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kl9U2-zvUCg [last accessed 18/July/2023]

- ↑ American Case Management Association. Scope of Services. Available from: https://www.acmaweb.org/section.aspx?sID=136 (accessed 18/July/2023).

- ↑ American Psychological Association. Clinical Psychology. Available from: https://www.apa.org/ed/graduate/specialize/clinical (accessed 18/July/2023).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 American Psychiatric Nurses Association. About PMH-APRNs. Available from: https://www.apna.org/about-psychiatric-nursing/about-pmh-aprns/?_gl=1*1tmyof4*_up*MQ..*_ga*MTY1OTIxMzcxOC4xNjg5Njk3Mzg2*_ga_79D3LBQT2E*MTY4OTY5NzM4NS4xLjEuMTY4OTY5NzYzOS4wLjAuMA..*_ga_4HD7QYR6T9*MTY4OTY5NzM4NS4xLjEuMTY4OTY5NzYzOS4wLjAuMA.. (accessed 18/July/2023).

- ↑ American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational Therapy Scope of Practice . Available from: https://research.aota.org/ajot/article/75/Supplement_3/7513410020/23136/Occupational-Therapy-Scope-of-Practice (accessed 18/July/2023).

- ↑ APTA Guide to Physical Therapist Practice 4.0. American Physical Therapy Association. Published 2023. Accessed 18/July/2023. https://guide.apta.org

- ↑ American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology. Available from: https://www.asha.org/policy/sp2016-00343/ (accessed 18/July/2023).

- ↑ Spiritual Care Association. Scope of Practice. Available from: https://www.spiritualcareassociation.org/docs/research/scope_of_practice_final_2016_03_16.pdf (accessed 18/July/2023).

- ↑ Gillham S, Clark L. NHS Improvement-Stroke Psychological care after stroke: Improving stroke services for people with cognitive and mood disorders.

- ↑ Ho FY, Yeung WF, Ng TH, Chan CS. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of stepped care prevention and treatment for depressive and/or anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2016 Jul 5;6(1):29281.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 American Psychological Association. What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?. Available from: https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/cognitive-behavioral (accessed 18 July 2023).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 International OCD Foundation. Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP). Available from: https://iocdf.org/about-ocd/ocd-treatment/erp/ (accessed 18/July/2023).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 International Society of Interpersonal Psychotherapy. Overview of IPT. Available from: https://interpersonalpsychotherapy.org/ipt-basics/overview-of-ipt/ (accessed 18/July/2023).

- ↑ Uphoff E, Ekers D, Robertson L, Dawson S, Sanger E, South E, Samaan Z, Richards D, Meader N, Churchill R. Behavioural activation therapy for depression in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020(7).

- ↑ Probst M. Psychomotor therapy for patients with severe mental health disorders. Occupational therapy-Occupation focused holistic practice in rehabilitation. 2017 Jul 5:26-47.