TMJ Anatomy

Original Editor - Heather Mariner

Top Contributors - Laurel, Janine Rose, Admin, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, Wendy Walker and Jess Bell

Description[edit | edit source]

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ), or jaw joint, is a synovial joint that allows the complex movements necessary for life. It is the joint between condylar head of the mandible and the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone. This system is made up of the TMJ, teeth and soft tissue and it plays a role in breathing, eating and speech.[1]

The TJM is defined as a ginglymoarthrodial joint[2] because it has a rotational movement in the sagittal plane and a translation movement on its own axis - this translation movement generates more movement.[3] These movements are constrained by various passive factors, as well as passive tension of the ligaments and muscles.[4]

Dysfunction of the TMJ can cause severe pain and lifestyle limitation.

Temporomandibular disorders are common and sufferers will often seek physiotherapy advice and treatment.

Good knowledge of the anatomy of the TMJ and related structures is essential to correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Joint[edit | edit source]

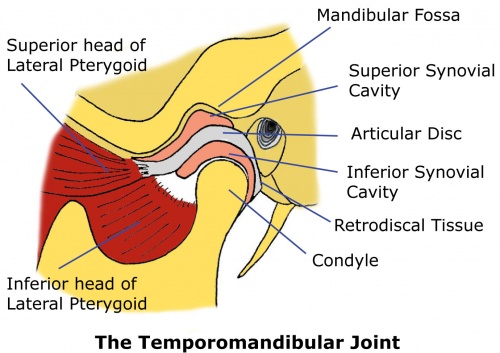

TMJ is a synovial, condylar and hinge-type joint. The joint involves fibrocartilaginous surfaces and an articular disc which divides the joint into two cavities.[5] These superior and inferior articular cavities are lined by separate superior and inferior synovial membranes[6].

Capsule - The capsule is a fibrous membrane that surrounds the joint and attaches to the articular eminence, the articular disc and the neck of the mandibular condyle.

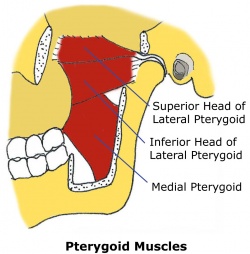

Articular disc - The articular disc is a fibrous extension of the capsule that runs between the two articular surfaces of the temporomandibular joint. The disc articulates with the mandibular fossa of the temporal bone above and the condyle of the mandible below. The disc divides the joint into two sections, each with its own synovial membrane. The disc is also attached to the condyle medially and laterally by the collateral ligaments. The anterior disc attaches to the joint capsule and the superior head of the lateral pterygoid. The posterior portion attaches to the mandibular fossa and is referred to as the retrodiscal tissue[7].

Retrodiscal tissue - Unlike the disc itself, the retrodiscal tissue is vascular and highly innervated. As a result, the retrodiscal tissue is often a major contributor to the pain of Temporomandibular Disorder (TMD), particularly when there is inflammation or compression within the joint[8]

Ligaments[edit | edit source]

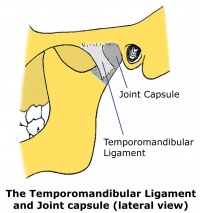

The ligaments give passive stability to the TMJ.

The temporomandibular ligament is the thickened lateral portion of the capsule, and it has two parts, an outer oblique portion and an inner horizontal portion.

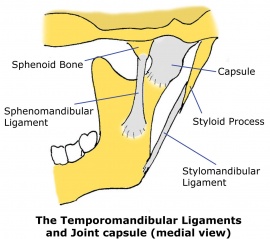

The stylomandibular ligament runs from the styloid process to the angle of the mandible. The sphenomandibular ligament runs from the spine of the sphenoid bone to the lingula of mandible.

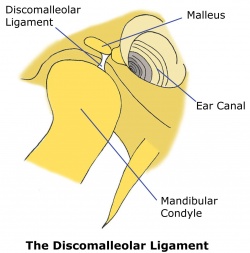

The oto-mandibular ligaments are the discomalleolar ligament (DML), which arises from the malleus (one of the ossicles of the middle ear) and runs to the medial retrodiscal tissue of the TMJ, and the anterior malleolar ligament (AML), which arises from the malleus and connects with the lingula of the mandible via the sphenomandibular ligament[9][10]. The oto-mandibular ligaments may be implicated in tinnitus associated with TMD. A positive correlation has been found between tinnitus and ipsilateral TMJ disorder[11][12]. It has been proposed that a TMJ disorder may stretch the DML and AML, thereby affecting middle ear structure equilibrium[13][14][15][16]. “It thus seems that otic symptoms (tinnitus, otalgia (ear pain), dizziness and hypoacusis) corresponding to altered ossicular spatial relationships (such as conductive middle ear pathologies) can also be produced from masticatory system pathologies.” [17]

Movements[edit | edit source]

A variety of movements occur at the TMJ. These movements are mandibular depression, elevation, lateral deviation (which occurs to both the right and left sides), retrusion and protrusion.

Each of these movements are performed by a number of muscles working together to perform the movement while controlling the position of the condyle within the mandibular fossa.

Chewing and talking require a combination of jaw movements in a number of directions[18][19].

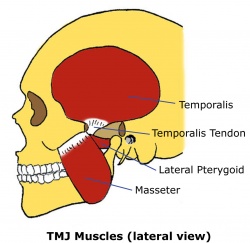

Muscles[edit | edit source]

For more detailed description, see the Muscles of Mastication page.

| Muscles | Actions |

|---|---|

| Temporalis | Elevates mandible |

| Masseter | Elevates mandible |

| Lateral pterygoid | Protracts mandible, depresses chin, lateral deviation of mandible |

| Medial pterygoid | Works with masseter to elevate mandible, aids in protrusion, |

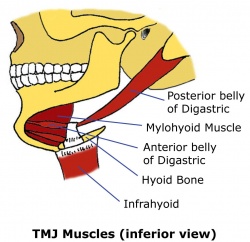

| Digastric

Stylohyoid Mylohyoid Geniohyoid |

Depresses the mandible against resistance when infrahyoid muscles stabilize or depress hyoid bone |

| Platysma | Depresses mandible against resistance |

Adapted from Moore[6]

|

|

|

Resting Position and Close-Packed Position[edit | edit source]

The resting position of the TMJ is with the mouth slightly open, the lips together and the teeth not in contact. This is in contrast to the closed-pack position in which the teeth are tightly clenched.[5]

Nerve Supply[edit | edit source]

The muscles that act on the TMJ are innervated by the mandibular nerve (CN V), the facial nerve (CN VII), C 1, C 2 and C 3.[6]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Di Fabio RP. Physical therapy for patients with TMD: a descriptive study of treatment, disability, and health status. Journal of orofacial pain. 1998 Apr 1;12(2).

- ↑ Maini K, Dua A. Temporomandibular Joint Syndrome. 2020 Nov 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 31869076.

- ↑ Reboredo V. Introduction to the Temporomandibular Joint Course. Plus. 2021.

- ↑ Abdi AH, Sagl B, Srungarapu VP, Stavness I, Prisman E, Abolmaesumi P et al. Characterizing motor control of mastication with soft actor-critic. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:188.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Magee DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2014

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AM. Clinically oriented anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017 Sept 13.

- ↑ Miloro, M; Ghali, GE; Larsen, P; Waite, P; Peterson's principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Volume 2, Chapter 47, 2004.

- ↑ Langendoen, J; Müller, J; Jull, GA, Retrodiscal Tissue of the Temporomandibular Joint: Clinical Anatomy and its Role in Diagnosis and Treatment of Arthropathies, Manual Therapy, 2(4), 191-198, 1997.

- ↑ Loughner BA, Larkin LH, Mahan PE. Discomalleolar and anterior malleolar ligaments: possible causes of middle ear damage during temporomandibular joint surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. Jul; 68(1):14-22, 1989.

- ↑ Rowicki, T; Zakrzewska, J. "A study of the discomalleolar ligament in the adult human." Folia Morphol. (Warsz). 65 (2): 121–125, 2006.

- ↑ Kuttila, S; Kuttila, M; Le Bell, BY; Alanen, P; Suonpaa, J. Recurrent tinnitus and associated ear symptoms in adults. Int. J. Audiol., 44:164-70, 2005.

- ↑ Ren, YF; Isberg, A. Tinnitus in patients with temporomandibular joint internal derangement. Cranio, 13:75-80, 1995.

- ↑ Cheynet, F; Guyot, L; Richard, O; Layoun, W; Gola, R. Discomallear and malleomandibular ligaments: anatomical study and clinical applications. Surg. Radiol. Anat., 25:152-7, 2003.

- ↑ Eckerdal, O. The petrotympanic fissure: a link connecting the tympanic cavity and the temporomandibular joint. Cranio, 9:15-22, 1991.

- ↑ Kim, HJ; Jung, HS; Kwak, HH; Shim, KS; Hu, KS; Park, HD; Park, HW; Chung, IH. The discomallear ligament and the anterior ligament of malleus: an anatomic study in human adults and fetuses. Surg. Radiol. Anat., 26:39-45, 2004.

- ↑ Wright, EF; Bifano, SL. Tinnitus improvement through TMD therapy. J. Am. Dent. Assoc., 128:1424-32, 1997.

- ↑ Ramírez, LM; Ballesteros, ALE; Sandoval, OGP. A direct anatomical study of the morphology and functionality of disco-malleolar and anterior malleolar ligaments. Int. J. Morphol., 27(2):367-379, 2009.

- ↑ Saladin, KS; Human Anatomy. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

- ↑ Standring, S, Editor, Gray’s Anatomy, 40th edition, Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

- ↑ Functional Anatomy of the TMJ. Movements of the TMJ. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SCS4MiHJ5Xw [last accessed 07/01/2018]