Low Back Pain in Distance Runners

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (31/08/2023)

Original Editor - Uploaded by Kim Jackson for Jerome Smith

Top Contributors - Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Low back pain (LBP) is the most common musculoskeletal condition in both the general population and in sport,[1] experienced by roughly 80% of adults[2][3] and between 66% and 88.5% of various athletic populations during their lifetime.[4][5][6]

Prior research has found that LBP in most athletes is a self-limiting overuse injury that has the potential to develop into persistent chronic LBP, degenerative disc disease and/or load-related spondylolytic injuries.[7]

Athletes participating in skiing, rowing, golf, volleyball, track and field, swimming and gymnastics appear to be most at risk, with incidence rates reported as high as 30% depending on the particular sport.[1][8] LBP has been widely studied in both the general population and in athletes, but there is a scarcity of evidence examining LBP in distance runners specifically.[1][7]

Distance running is an increasingly popular form of exercise in the general population[7][9] due in part to its relatively low cost and multiple health benefits, including weight control and chronic disease prevention.[1][8]

As the level of interest in both competitive and recreational distance running appears to increase, recent studies suggest distance running carries a significant risk of injury.[1] [7]Numerous studies to date have examined running-related injuries (RRIs) in general, but few have focussed on the relationship between distance running and LBP.[1][7]

Prevalence and Incidence[edit | edit source]

A systematic review by Maselli et al.[1] represents the highest level of evidence on this topic published in that past five years.[10] The study reviewed case-control and cohort studies across a range of distance running populations, excluding case reports and other descriptive observational designs.

Research findings:

- Overall prevalence and incidence of low back pain in distance runners aged 20-50 is low (0.7-20.2% and 0.3-22% respectively).[1]

- This is lower compared to other running injuries,[1][8] to non-runners of the same age[1] and compared to many other sport-specific populations.[11][12][13]

This suggests that distance running may in fact have a protective effect against the onset of low back pain.[1][8]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

The prevalence of LBP appears to vary across certain groups within distance running.

For example:

- The average prevalence of LBP in both elite marathon runners and recreational half marathon runners has been reported at 14%.[1]

- Similarly, the prevalence in ultra-distance athletes is estimated to be 12-14%, with LBP more commonly encountered during training.[14]

- The highest prevalence has been found in ultra-trail runners at >20%.[15]

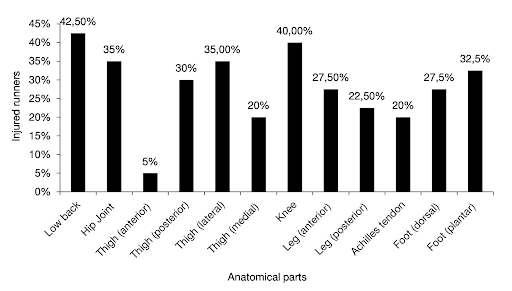

- Low back injuries have been found to account for >40% of all injuries reported by ultra-trail runners.[15]

From Malliaropoulos et al.[15] showing injury distribution by anatomical region in ultra-trail runners.

It is worth noting that ultra-distances are beyond the distance of a regular marathon and can exceed distances of 100km.[1]

Ultra-trail runners specifically train and race on different terrain to regular distance runners, for example in mountains, deserts and forests with greater uphill and downhill sections.1 These factors may explain the higher prevalence seen in ultra-trail athletes.

Mileage and Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Aside from ultra-distances, the prevalence of LBP appears to be otherwise unrelated to mileage in distance runners. In a larger sample of 4380 runners competing in races of 10km, 21km and 42km, it was found that the rate of prevalence in the marathon group (7.5%) was identical to the rate in the half marathon group (7.5%).[16]. This suggests that despite there being variations in the prevalence of LBP at different distances, prevalence does not correlate reliably with mileage.[16]

This concept is consistent with prior research that compared the training mileage of injured runners to non-injured runners and found no statistically significant difference.[17]. Further research might investigate an association between training load spikes and LBP in runners, as the ratio between chronic and acute workloads in other sports such as rugby[18] has been shown to provide a better prediction of injury than absolute workload in isolation.

Incidence[edit | edit source]

The large majority of authors cited in Maselli et al.’s[1] systematic review report the incidence of LBP to be less than 5% across various populations of distance runners, including men, women and novice runners.

Only one prospective study provided evidence to the contrary, where an incidence rate of 22% was reported in a small sample of 45 runners.[19] Two thirds of these runners were found to be sitting 50-75% of the day, which has been associated with shortening of the iliopsoas and rectus femoris muscles.[19]

Previous research has linked hip flexor tightness with both running injuries and LBP,[20] which may explain the higher rate of incidence in this particular sample.[19].Due to the scarcity of available studies, the conclusion that the prevalence and incidence of LBP in distance runners is universally low should be drawn with caution.

Both the prevalence and incidence of LBP in the general population have been shown to increase with age,[21] therefore further studies are needed to confirm that the same results apply to distance runners in the older adult population.[1] These would ideally be large cohort studies that utilise a standardised definition of LBP.[1]

The heterogeneity of participants in these studies is also problematic, as individual characteristics such as age, sex, training level and previous injuries are not accounted for.[1]. Sampling specific running populations such as young elite athletes or middle-aged recreational runners is likely to produce different prevalence and incidence rates, such is the case with ultra-trail runners.[1][15]

A systematic review of homogenous studies would be the ideal design to address this issue and would enable meta-analysis of prevalence and incidence within specific running populations to be conducted.

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Maselli et al.’s systematic review[1] has identified the most common risk factors for LBP in distance runners.

Intrinsic Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Evidence from Maselli et al.[1] suggests that certain physical characteristics are related to the risk of developing LBP in a distance runner. Intrinsic risk factors commonly reported include:

- A body mass index (BMI) of 24 or higher

- Greater physical height

- Greater hip flexion angle

- Leg length discrepancy

- Poor hamstring flexibility

- Poor lumbar flexibility

Hip Flexion Angle[edit | edit source]

One retrospective study reviewed by Ellapen et al.[17] found that hip flexor tightness - as defined by a positive Thomas test and hip flexion angle measurements taken with a goniometer - was a potential intrinsic factor predisposing runners to LBP.

Thomas test video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oqirNScoqpE

Measuring hip flexion angle - https://www.physio-pedia.com/Goniometry:_Hip_Flexion

It was found that female half-marathon runners with LBP and hip injuries had significantly higher hip flexion angles compared to non-injured female runners in the same sample.[17]

It is suggested that tightness in the hip flexor muscle group contributes to an increased anterior pelvic tilt, whereby the normal length-tension relationship between the posterior hip rotators/extensors and the anterior hip rotators/flexors is altered.[17]

This abnormal force couple is thought to cause muscle spasms in the hip flexors and contribute to the development of LBP.[17]

Uneven Shoe Wear[edit | edit source]

A cross-sectional study by Woolf et al.[22] identified that runners with a previous history of LBP were more likely to report increased shoe wear on either the inside or outside of the sole.

Similarly, those runners who demonstrated even shoe wear were less likely to report a history of LBP (p=0.034).[22] These findings suggest that a relationship exists between LBP and variations in lower limb biomechanics among distance runners.

Other Intrinsic Factors[edit | edit source]

Other intrinsic risk factors such as leg length discrepancy, hamstring tightness and lumbar flexibility have only been identified using qualitative methods and have not been evaluated in large samples using statistical analysis.[1]

It has been recommended that these physical impairments are investigated further, preferably in large homogenous samples using a prospective design.[1]

A recent study has found that biomechanical loading asymmetries did not correlate with the laterality of sacral stress fractures in a small sample of 10 endurance athletes, concluding that observable biomechanical abnormalities were unreliable risk factors for injury.[23]

This highlights that physical impairments may not always increase the risk of developing LBP in all individuals and therefore should not be considered in isolation.

Extrinsic Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Common extrinsic risk factors reported by Maselli et al.[1] include:

- A highly competitive level

- A history of running for longer than six years

- A lack of weekly aerobic exercise

More recently, cross-sectional data[7] has identified additional risk factors such as:

- A sedentary occupation

- Insufficient warm-up activity

- Fatigue

- Poor running gait posture

- An uncomfortable environmental temperature

Sedentary Occupation[edit | edit source]

A sedentary occupation has recently been identified as the most important risk factor for LBP in distance runners.[7]

Occupational factors are known to play a significant role in the development of LBP.[24] In this case, the prolonged static loads acting on the sedentary spine are thought to be responsible for the heightened risk.[7]

Warm-up Activity[edit | edit source]

Warm-up activities are said to improve physiological and psychological preparedness for running by activating muscles which control and stabilise the lumbar spine and pelvis.[7]

Insufficient warm-up therefore presents a risk of injury in runners.7 It is recommended that warm-up activities should be appropriately dosed before training and competition as to avoid fatigue and other negative effects on performance.[7]

Fatigue[edit | edit source]

Fatigue has been described as an important risk factor that increases mechanical loads in the lumbar spine in runners and has the potential to cause LBP.[7][25]

In addition, fatigue can lead to altered immune function, reproductive function and physical self-perception, leading to a state of stress-related neuro-endocrine dysregulation in the athlete.[7]

This has been described elsewhere as the ‘overtraining syndrome’.[26]

Poor Running Gait Posture[edit | edit source]

Poor running gait posture has been linked to LBP in a large sample of marathon runners,[7] supporting existing theories that posture and biomechanics are inter-related and inefficient biomechanics naturally carries an energy cost that results in fatigue.[27]

Further studies in this field are essential in developing a better definition of optimal gait which can account for the diversity in stride patterns and lower limb kinematics seen across different running populations .[28][29]

Environmental Temperature[edit | edit source]

Changes in ambient temperature are known to stimulate the central nervous system via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic-adrenomedullary system (SAS),[30] causing a wide range of systemic physiological effects, including cardiovascular and respiratory effects.[31]

There is currently little evidence to show how these physiological effects play a role in LBP.

Nonetheless, it is recommended that athletes should always acclimate to training and competition environments, particularly in regards to ambient temperature.[7]

Orthotic Use[edit | edit source]

Low back pain is more likely to be reported by runners not using orthotics (including inserts, insoles, heel cups, custom foot-beds, etc).[22]

This suggests that foot morphology may play a role in LBP in runners and helps validate the use of orthotics in the clinical management of LBP in a distance runner.

Sports Participation[edit | edit source]

Runners who regularly played contact sports such as football, basketball, wrestling, boxing and rugby, were less likely to have a previous history of LBP than those who did not.[22]

This supports prior research by Maselli et al.8 that suggests other sports such as cycling and soccer may offer a protective benefit against LBP for runners.

Management of Risk Factors in Clinical Practice[edit | edit source]

Most risk factors relate to physical factors and training methods, which can be managed and modified clinically with specific interventions and training adaptations.[1]

This might include:

- Changes to training volume, frequency and other variables.[32]

- Ensuring sufficient strength training is completed.[7]

- Using appropriate sports equipment (notably shoes).[32]

- Acclimating to the training and competition environment.[32][33]

- Ensuring adequate warm-up before running.[7]

It would be useful to investigate how specific risk factors affect the lumbar spine individually, or whether these factors are structure-specific.

In particular, further research that trials the dose-response relationship between running and LBP would allow researchers to better quantify risk and aid the development of evidence-based preventative guidelines.[34]

In the meantime, clinicians should avoid relying on a single risk factor to predict running-related injuries, as exposure to a single risk factor rarely results in an overuse injury.[1]

More commonly, RRIs result from exposure to multiple risk factors simultaneously such as training errors, physical impairments and unsuitable footwear.[16]

[edit | edit source]

The multifactorial nature of RRIs has also led some to believe that running-related 'injury' should be re-categorised as running-related 'disorder', to reflect the broad range of factors common in other non-specific conditions such as LBP.[1]

These have been identified previously by Lederman[35] and may include:

- Psychosocial factors

- Sleep quality

- Nutrition

- Occupational factors

- Comorbidities

These factors form part of the broader biopsychosocial model of pain prevention and management.

Interventions for Low Back Pain in Distance Runners[edit | edit source]

Cai et al.[36] have presented level 1b evidence for lower limb strength exercises in the clinical management of non-specific chronic low back pain (cLBP) in recreational runners.

A single-blind randomised trial compared lower limb exercises with conventional back exercises for runners with chronic low back pain and found that lower limb exercise therapy was more effective in improving self-rated running capability, knee extension strength and running step length.[36]

Specifically, these exercises were machine hip abduction and extension, leg press, single leg squat and wall-sit.[36]

The 8-week lower limb exercise protocol was as follows:

- Resistance training (hip abduction, hip extension and leg press)

- 2 sessions per weeks

- 3 sets of 10 repetitions per exercise

- Intensity of 10 repetition maximum (10RM)*

- 2 minutes rest between sets

*10RM is re-estimated at week 5 and used for the remaining 4 weeks

- Home exercises (single-leg squat and wall-sit)

- Performed every day except on resistance machine training days

- 3 sets of 10 repetitions or 10 seconds on wall-sit

- From week 5 onward, 2.5kg weight held during single-leg squat and 5kg weight held during wall-sit

Note: participants performed general stretching exercises and 15 minutes of stationary cycling before resistance training.36

The authors suggest that improvements in the knee strength of runners in this study is likely responsible for the higher self-rated running capability,[36] supporting a pre-existing hypothesis that weak knee extensors transmit higher loads to the lumbar spine in runners with cLBP.[37]

Although this study represents the highest level of evidence currently available for the management of cLBP in runners, the findings may not apply to long-distance runners as inclusion criteria specified a minimum running distance of only 2km.

Further trials involving distance runners specifically would offer clinicians superior evidence for managing LBP in this group.

Distance Running as Preventative Exercise for Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

The key finding of low prevalence and incidence of LBP in distance runners compared to the general population suggests distance running could be considered by clinicians as preventative exercise for LBP.[1][8]

This is consistent with the notion that running in general is an effective strategy to maintain a healthy lifestyle, as recommended by the World Health Organisation.[38]

At present, this recommendation should be considered in the 20-50 age group only, which is consistent with samples found in the recent literature.[1]

Intervertebral Disc (IVD) Studies[edit | edit source]

Multiple studies have suggested that running, among other sports,[39] stimulates an anabolic response in the IVD, with one study in particular demonstrating superior hydration (glycosaminoglycan content) in the IVDs of distance runners.[40]

It remains unclear however whether disc hydration correlates negatively with LBP in distance runners.

Recent MRI studies have challenged concerns raised previously about the impact of marathon running on spine health,[9][39]particularly in regard to the IVD.[41]

One study conducted by Horga et al.[9] concluded that marathon training had no observable effects on the extent of lumbar disc degeneration, disc height or intervertebral distance in 28 asymptomatic adults. This was true despite early degenerative changes being found in some individuals.[9]

Another MRI study by Owen et al. found greater IVD hypertrophy in runners compared to non-sporting controls, concluding that the intradiscal pressures seen in running are likely to be within a beneficial range of 0.3 to 1.2MPa.[39]

Longitudinal data will be critical in testing the reliability of these observations in the long term.

The potential use of exercise training to stimulate IVD hypertrophy has been compared to the use of progressive resistance training for muscle atrophy,[39] and may have the potential to reduce the burden of disease for IVD-related LBP.[39]

Further studies are needed to examine this effect in distance running and add evidence to the potential use of distance running as safe and effective preventative exercise for LBP.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Main findings:

- Research evidence has found that the prevalence of LBP in distance runners is generally low[1] and does not correlate reliably with mileage.[16]

- The risk of LBP in distance running is strongly multifactorial but can be managed clinically with a range of specific interventions and training adaptations.[1]

- Lower limb strength training has been shown to improve self-rated running capability, knee extension strength and running step length in runners with LBP.[36]

Running may promote therapeutic responses in the disc 39,40 and shows potential as a preventative strategy for LBP in the 20-50 age group.[1]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 Maselli F, Storari L, Barbari V, Colombi A, Turolla A, Gianola S, et al. Prevalence and incidence of low back pain among runners: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Jun 3;21(1)

- ↑ Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Traeger AC, Lin CWC, Chenot JF, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. European Spine Journal [Internet]. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Jun 23];27(11):2791–803. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2

- ↑ Rubin DI. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Spine Pain. Neurol Clin. 2007 May 1;25(2):353–71

- ↑ Schmidt CP, Zwingenberger S, Walther A, Reuter U, Kasten P, Seifert J, et al. Prevalence of low back pain in adolescent athletes - An epidemiological investigation. Int J Sports Med [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2023 Jun 23];35(8):684–9. Available from: http://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/s-0033-1358731

- ↑ Purcell L, Micheli L. Low Back Pain in Young Athletes. Sports Health [Internet]. 2009 May [cited 2023 Jun 23];1(3):212. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3445254/

- ↑ Fett D, Trompeter K, Platen P. Back pain in elite sports: A cross-sectional study on 1114 athletes. PLoS One [Internet]. 2017 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Jun 23];12(6). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5491135/

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 Wu B, Chen CC, Wang J, Wang XQ. Incidence and Risk Factors of Low Back Pain in Marathon Runners. Pain Res Manag. 2021;2021

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Maselli F, Esculier JF, Storari L, Mourad F, Rossettini G, Barbari V, et al. Low back pain among Italian runners: A cross-sectional survey. Physical Therapy in Sport. 2021 Mar 1;48:136–45

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Horga LM, Henckel J, Fotiadou A, Di Laura A, Hirschmann AC, Lee R, et al. What happens to the lower lumbar spine after marathon running: a 3.0 T MRI study of 21 first-time marathoners. Skeletal Radiol. 2022 May 1;51(5):971–80.

- ↑ Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (March 2009) — Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), University of Oxford [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009

- ↑ Farahbakhsh F, Rostami M, Noormohammadpour P, Mehraki Zade A, Hassanmirazaei B, Faghih Jouibari M, et al. Prevalence of low back pain among athletes: A systematic review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2018 Jan 1;31(5):901–16

- ↑ Trompeter K, Fett D, Platen P. Prevalence of Back Pain in Sports: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sports Med [Internet]. 2017 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Jun 23];47(6):1183. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5432558/

- ↑ D’Hemecourt PA, Gerbino PG, Micheli LJ. Back injuries in the young athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2000 Oct 1;19(4):663–79

- ↑ Scheer V, Krabak BJ. Musculoskeletal Injuries in Ultra-Endurance Running: A Scoping Review. Vol. 12, Frontiers in Physiology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2021

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Malliaropoulos N, Mertyri D, Tsaklis P. Prevalence of Injury in Ultra Trail Running. Human Movement. 2015 Jun 1;16(2):52–9

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Besomi M, Leppe J, Mauri-Stecca M V, Hooper TL, Sizer PS. Training volume and previous injury as associated factors for running-related injuries by race distance: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Jun 20];14(3):549–59. Available from: https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2019.143.06

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Ellapen T, Satyendra S, Morris J, Van Heerden H. Common running musculoskeletal injuries among recreational half-marathon runners in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013 Jun 15;25(2):39

- ↑ Hulin BT, Gabbett TJ, Lawson DW, Caputi P, Sampson JA. The acute:chronic workload ratio predicts injury: high chronic workload may decrease injury risk in elite rugby league players. Br J Sports Med [Internet]. 2016 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Jun 28];50(4):231–6. Available from: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/4/231

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Bach DK, Green DS, Jensen GM, Savinar E. A Comparison of Muscular Tightness in Runners and Nonrunners and the Relation of Muscular Tightness to Low Back Pain in Runners. https://doi.org/102519/jospt198566315 [Internet]. 1985 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Jun 23];6(6):315–23. Available from: https://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.1985.6.6.315

- ↑ Slocum DB, James SL. Biomechanics of Running. JAMA [Internet]. 1968 Sep 9 [cited 2023 Jun 27];205(11):721–8. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/340602

- ↑ Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Xavier Faria NM. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Rev Saude Publica [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Jun 20];49:1. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4603263/

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Woolf SK, Barfield WR, Nietert PJ, Mainous AG, Glaser JA. The Cooper River Bridge Run Study of low back pain in runners and walkers. J South Orthop Assoc [Internet]. 2002 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Jun 23];11(3):136–43. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/12539937

- ↑ Riedl M, Roediger J, Pohlmann J, Hesse J, Warschun F, Wolfarth B, et al. Laterality of sacral stress fractures in trained endurance athletes: Are there biomechanical or orthopaedic risk factors? Sports Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 2022 Mar 1;38(1):36–46

- ↑ Snook SH. Work-related low back pain: secondary intervention. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2004 Feb 1;14(1):153–60

- ↑ Solomonow M. Neuromuscular manifestations of viscoelastic tissue degradation following high and low risk repetitive lumbar flexion. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2012 Apr 1;22(2):155–75

- ↑ Angeli A, Minetto M, Dovio A, Paccotti P. The overtraining syndrome in athletes: A stress-related disorder. J Endocrinol Invest [Internet]. 2004 Apr 2 [cited 2023 Jun 24];27(6):603–12. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF03347487

- ↑ Folland JP, Allen SJ, Black MI, Handsaker JC, Forrester SE. Running Technique is an Important Component of Running Economy and Performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Jun 24];49(7):1412. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5473370/

- ↑ Nummela A, Keränen T, Mikkelsson LO. Factors related to top running speed and economy. Int J Sports Med [Internet]. 2007 Aug [cited 2023 Jun 24];28(8):655–61. Available from: http://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/s-2007-964896

- ↑ Casado A, Hanley B, Jiménez-Reyes P, Renfree A. Pacing profiles and tactical behaviors of elite runners. J Sport Health Sci. 2021 Sep 1;10(5):537–49

- ↑ Maughan RJ. Distance running in hot environments: a thermal challenge to the elite runner. Scand J Med Sci Sports [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2023 Jun 24];20(SUPPL. 3):95–102. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01214.x

- ↑ Maughan RJ, Watson P, Shirreffs SM. Heat and cold: What does the environment do to the marathon runner? Sports Medicine [Internet]. 2007 Nov 29 [cited 2023 Jun 24];37(4–5):396–9. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00007256-200737040-00032

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Bahr R, Krosshaug T. Understanding injury mechanisms: a key component of preventing injuries in sport. Br J Sports Med [Internet]. 2005 Jun [cited 2023 Jun 23];39(6):324. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1725226/

- ↑ Malisoux L, Nielsen RO, Urhausen A, Theisen D. A step towards understanding the mechanisms of running-related injuries. J Sci Med Sport [Internet]. 2015 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Jun 20];18(5):523–8. Available from: http://www.jsams.org/article/S1440244014001406/fulltext

- ↑ Bertelsen ML, Hulme A, Petersen J, Brund RK, Sørensen H, Finch CF, et al. A framework for the etiology of running-related injuries. Scand J Med Sci Sports [Internet]. 2017 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Jun 21];27(11):1170–80. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/sms.12883

- ↑ Lederman E. A process approach in manual and physical therapies: beyond the structural model. CPDO Online Journal. 2015;1:18.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Cai C, Yang Y, Kong PW. Comparison of Lower Limb and Back Exercises for Runners with Chronic Low Back Pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017 Dec 1;49(12):2374–84

- ↑ Cai C, Kong PW. Low back and lower-limb muscle performance in male and female recreational runners with chronic low back pain. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2015 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Jun 24];45(6):436–43. Available from: https://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.2015.5460

- ↑ Global recommendations on physical activity for health [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 Owen PJ, Hangai M, Kaneoka K, Rantalainen T, Belavy DL. Mechanical loading influences the lumbar intervertebral disc. A cross-sectional study in 308 athletes and 71 controls. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2021 May 1;39(5):989–97.

- ↑ Belavý DL, Quittner MJ, Ridgers N, Ling Y, Connell D, Rantalainen T. Running exercise strengthens the intervertebral disc. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2017 Apr 19 [cited 2023 Jun 21];7. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5396190/

- ↑ Mitchell UH, Bowden JA, Larson RE, Belavy DL, Owen PJ. Long-term running in middle-aged men and intervertebral disc health, a cross-sectional pilot study. PLoS One [Internet]. 2020 Feb 1 [cited 2023 Jun 26];15(2). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7034897/