Overview of Global Health

Top Contributors - Jess Bell, Robin Tacchetti and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

There have been many discussions about global health in recent years, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic. Discussions centred on global health equity and other social movements such as diversity, equity and inclusion, and racial equity have garnered public attention. Rehabilitation professionals can play an important role within the health system in achieving health equity, especially given the current epidemiological transition towards an increasing burden of non-communicable diseases globally.

This page critically examines what global health means and how the history of global health has influenced current practice and discussion. It also aims to illustrate the importance of recognising power, culture and social constructs as structural determinants that impact health equity.

What Is Health?[edit | edit source]

There are numerous definitions of health, including the following:[1]

“The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition”[2] - WHO Constitution (1946)

“Health is a social, economic and political issue and above all a fundamental human right. Inequality, poverty, exploitation, violence and injustice are at the root of ill‐health and the deaths of poor and marginalised people. Health for all means that powerful interests have to be challenged, that globalisation has to be opposed, and that political and economic priorities have to be drastically changed. […] Health is a reflection of a society’s commitment to equity and justice. Health and human rights should prevail over economic and political concerns.”[3] - People’s Health Movement

Key points:[1]

- The World Health Organization states that health is a fundamental human right inherent to all human beings and that these rights are indivisible, interdependent, and non-discriminatory.[2]

- This acknowledgement recognises that health is "a legal obligation on states to ensure access to timely, acceptable, and affordable health care."[2]

- Adopting a Human Rights-based Approach (HRBA) to health provides a framework to analyse health policies and programmes and other social and government policies that directly influence the many determinants that impact different population groups.

It is also important to emphasise that political power and socioeconomic and cultural environments are structural and central to health outcomes. Injustices within these domains, such as gender inequalities or class discrimination, contribute directly towards the observable and measurable health inequalities that exist locally, nationally and globally.[1]

For more information, please see World Health Organization: Human Rights.

History of Global Health[edit | edit source]

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)'s Framework for Action on Global Health Research outlines how our concept of global health has changed over time.

- Initially, we had what could be termed Global Health 1.0 or "tropical medicine". This area of health was very much connected with the legacy of colonialism and imperialism. It was conceived as "Protection of colonial representatives from tropical diseases".

- This concept morphed and changed into what has been termed Global Health 2.0. In this model, the focus was on wealthier countries helping those with less.

- Finally, we currently have what is termed Global Health 3.0 where there is "Collective action to address shared risks and responsibilities".

To read more about the framework outlined by the CIHR, please see: Global Health 3.0. CIHR's Framework for Action on Global Health Research 2021-2026.

Defining Global Health[edit | edit source]

There is no universally accepted definition of global health.[4][5] In 2009, Koplan et al.[6] attempted to create a common definition for global health, distinct from the related areas of public health and international health.[4]

- According to Koplan et al.,[6] the modern concept of public health developed in the mid-19th century in England, Europe and the United States "as part of both social reform movements and the growth of biological and medical knowledge (especially causation and management of infectious disease)"[6]

- International health can be traced back to "colonial roots in hygiene and tropical medicine (TM) through to the mid-20th century with its geographic focus on developing countries."[4]

It is important to acknowledge the historical emergence of global health as a discipline from tropical medicine to international health in order to understand the current governance, epistemology (i.e. knowledge) and hegemony (i.e. leadership or dominance).[1]

A recent systematic review by Salm et al.[4] explored the current definitions for global health. In this review, the authors attempted to determine if a "common conceptualisation" of global health has been established and identified the following themes:[4]

- Global health is a "multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement" and a form of expertise taught and pursued through research institutions[4]

- It is a domain of research, healthcare and education

- It is multifaceted ("disciplinary, sectoral, cultural, national")

- Global health is an "ethical initiative that is guided by justice principles"[4]

- It has its roots in values like equity and social justice

- Global health is a mode of governance that yields influence through political decision-making, problem identification, and the allocation and exchange of resources across borders[4]

- It is a political field that includes power relations at multiple scales

- It is determined by globalisation and international interdependence

- Issues related to global health cross national borders

- It is problem-oriented

- Global health has many meanings with "historical antecendents and an emergent future"[4]

- It is "dis/similar" to public health, international health and tropical medicine

- The definition for global health remains vague

For more information, please read: Defining global health: findings from a systematic review and thematic analysis of the literature.[4]

To learn more about power, representation and visibility, please see: Envisioning the futures of global health: three positive disruptions.[7]

Terminology[edit | edit source]

Often, global health is discussed, viewed and prioritised from a Global North perspective in response to health conditions in the Global South. The terms Global North/Global South are commonly used in the public discourse. However, it is important to recognise the limitations of this framing as a terminology. Countries and minority groups in the Northern Hemisphere have undergone a colonial history, systems of oppression and inequalities.

Other terms used include Global Majority (Global South) to represent the collective group of racialised “minority groups” vs. Global Minority (Global North). It is also common to see countries categorised as high-income and low- and middle-income countries in the literature.[1]

Holst[8] provides an overview of the origin of global health while presenting different approaches and perspectives on how “Global Health” work is carried out amongst different actors and spheres. This paper encourages us to be critical and reflect on whether global collaboration and development address structural determinants and root causes that lead to health inequalities. Examples of structural determinants include the oppression of marginalised communities, knowledge production and epistemology, power within decision-making circles and the continuation of extractive ideologies that worsen climate-related health burdens.

For more information on these topics, please read:

- Global Health - emergence, hegemonic trends and biomedical reductionism[8]

- Dismantling and reimagining global health education[9]

- What Is Global Health

As discussed in these linked papers, the majority of global health research, education and knowledge are produced in the Global North / Global Minority. Health professionals must be critical of whether this unilateral position of power, ideology and health model addresses systemic causes of health inequalities in the Global South / Global Majority. Do current models, leadership, and global health partnerships promote the advancement, agency and voice of the often marginalised communities? Or do they continue to upkeep systems of power through the promise of innovation and development?[1]

Interconnected Systems[edit | edit source]

When considering health and global health, we must also explore other interconnected systems.

- Economics: Neoliberalism has affected healthcare and for-profit healthcare around the world, creating a significant wealth gap in many countries. In terms of rehabilitation and healthcare services, this gap affects who can access appropriate services.[1]

- Food: It is important to understand the global food system and how it affects our food supply, food sovereignty and nutrition value. Regarding rehabilitation and healthcare, we must consider that food is our body's source of fuel and that where/how we get food influences our mental health and impacts non-communicable diseases.[1]

- Climate and the environment: With climate change, we must consider how heat exposure and increasing temperatures influence physical activity, manual work, etc.[1] It is also important to note that various factors, including climate change, urbanisation, the migration and trade of animals, travel and tourism, etc. have all had an impact on the development, re-emergence and spread of zoonoses (i.e. a disease / infection that is transmitted from vertebrate animals to humans or humans to animals).[10] A number of factors have been identified as triggers for the development of zoonotic diseases, including changes in:

- human and animal behaviour.

- habitat

- ecology

- vector biology

- pathogen adaptability

- change in farm practices

- livestock production systems

- food safety

- urbanisation

- deforestation

- climate change

- One Health:[11] This framework considers the connected system between animal, environment, and human health.[1]

- The concept of One Health has been around for at least 200 years - initially, it was known as One Medicine, then One World, One Health and now One Health.[11]

- Again, there is no single definition for One Health. Most commonly, it is defined as: "a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach—working at the local, regional, national, and global levels—with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes recognizing the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment".[11]

- One Health considers "consequences, responses, and actions at the animal–human–ecosystems interfaces",[11] including:

- the increased burden of disease (particularly in resource-poor settings) due to emerging and endemic zoonoses

- antimicrobial resistance in humans, animals, or the environment

- food safety

- However, it is important to note that One Health also considers various disciplines and domains, environmental and ecosystem health, social sciences, ecology, wildlife, use of land and biodiversity.[11]

- Factors at a community level: We must understand how certain social constructs (e.g. gender, class, race) impact an individual's agency, empowerment and advocacy when obtaining healthcare.

Determinants of Health[edit | edit source]

The many interconnected factors that impact health and health outcomes are referred to as determinants of health. Examples of determinants of health can include genetics, behaviour, environment and physical influences, medical care, social and structural determinants.

Social determinants of health (SDH) are the circumstances in which we are born, develop, live, earn, and age. SDH include economic conditions, housing, nutrition, the environment, transportation, and education.[12]

WHO defines social determinants of health as “complex, integrated, and overlapping social structures and economic systems that include the social environment, physical environment, and health services; structural and societal factors that are responsible for most health inequities. Social determinants of health are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national, and local levels, which are themselves influenced by policy choices."

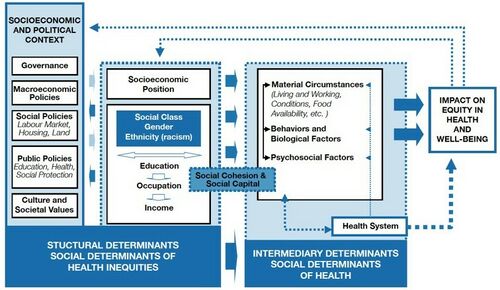

Structural determinants are upstream root causal factors that influence downstream determinants and health conditions. Examples include, but are not limited to, power, education, economic system, land policies and social positions.[1] The WHO Conceptual Framework illustrates the relationship between structural and intermediary determinants of health and their impact on health equity (see Figure 1).

Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, recent social movement and the increasing discussion on diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives across all sectors, it is vital to understand how racism, xenophobia and discrimination are structural determinants of health.[1] The Lancet recently published a series of papers illustrating how these determinants intersect with systems of power, such as politics, education, and scientific knowledge production, that continue to impact health equity across minority groups. It is important as rehabilitation professionals to recognise and examine how these social constructs influence many levels of our healthcare system, spanning leadership research, biases and patient contact.

See these articles here:

- Racism, xenophobia, discrimination, and the determination of health

- Racism, xenophobia, and discrimination: mapping pathways to health outcomes

- Intersectional insights into racism and health: not just a question of identity

- Confronting the consequences of racism, xenophobia, and discrimination on health and health-care systems

Key Points[edit | edit source]

- Global health must consider more than just medical care - it must also address "other underlying drivers of health, social and political determinants, and non-health sectoral issues."[5]

- If we are to improve outcomes and achieve equity in health, global health must also consider culture, human behaviour, governance, law, politics, various regulations, and institutional frameworks.[13]

- Power dynamics in global health have tended to undervalue research from low- and middle-income countries.[13]

For more information on power asymmetries in global health, please see:

- Who is a global health expert?[13]

- Addressing power asymmetries in global health: Imperatives in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic[14]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

It is important to recognise the enormous gains achieved over the last several decades in global health. However, we are also able to think and live beyond a dichotomous lens, and examine the health and social inequities that continue to be perpetuated by structural injustices to marginalised communities around the world.

This page has attempted to illustrate the complexity and interconnectedness across numerous systems that intersect with pain, disability and rehabilitation outcomes. It is long overdue to recognise that marginalised communities are experts of their experiences, as opposed to the historic unidirectional flow of expertise, aid and solutions. An equitable inclusion and implementation of their knowledge, needs and voice within global health strategies are imperative to achieve transformative gains within health equity around the world.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Lai D. Global Health for Rehabilitation Professionals Course. Plus, 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 World Health Organization. Human Rights. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health (last accessed 22 September 2023).

- ↑ People's Health Movement. People's Charter for Health. Available from https://phmovement.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/phm-pch-english.pdf (last accessed 22 September 2023).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Salm M, Ali M, Minihane M, Conrad P. Defining global health: findings from a systematic review and thematic analysis of the literature. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Jun;6(6):e005292.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ojiako CP, Weekes-Richemond L, Dubula-Majola V, Wangari MC. Who is a global health expert? PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023 Aug 17;3(8):e0002269.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009 Jun 6;373(9679):1993-5.

- ↑ Sewankambo NK, Wallengren E, De Angeles KJC, Tomson G, Weerasuriya K. Envisioning the futures of global health: three positive disruptions. Lancet. 2023 Apr 15;401(10384):1247-9.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Holst J. Global Health - emergence, hegemonic trends and biomedical reductionism. Global Health. 2020 May 6;16(1):42.

- ↑ Gichane MW, Wallace DD. Dismantling and reimagining global health education. Glob Health Action. 2022 Dec 31;15(1):2131967.

- ↑ Rahman MT, Sobur MA, Islam MS, Ievy S, Hossain MJ, El Zowalaty ME, et al. Zoonotic diseases: etiology, impact, and control. Microorganisms. 2020 Sep 12;8(9):1405.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Mackenzie JS, Jeggo M. The One Health approach-why is it so important? Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019 May 31;4(2):88.

- ↑ World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health (last accessed 1 September 2023).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Ojiako CP, Weekes-Richemond L, Dubula-Majola V, Wangari MC. Who is a global health expert? PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023 Aug 17;3(8):e0002269.

- ↑ Abimbola S, Asthana S, Montenegro C, Guinto RR, Jumbam DT, Louskieter L, et al. Addressing power asymmetries in global health: Imperatives in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS Med. 2021 Apr 22;18(4):e1003604.