Feasibility of Applying a Simple Method to Quantify Clinical Experience: A Case Report

Original Editor - Selena Horner

Click here to view or contrinute to the Open Peer Review

Abstract

[edit | edit source]

Concrete awareness of clinical experience more readily allows for the integration of clinical expertise and patient preferences with published literature. A process for quantifying clinical experience has not been established. This case report describes the development and implementation of a process physical therapists may incorporate to quantify clinical experience in an outpatient physical therapy setting to assist with clinical decision-making. The process involves three distinct phases: Phase I (preparation), Phase II (altering the process involved in the delivery of care) and Phase III (procedural changes after the episode of care). Implementation occurs on a sample of 296 consecutive episodes of care for patients with a predominant orthopaedic complaint. Summary reports comprise the final outcome of the process. The value of the process resides at the level of the individual clinician. The ability of the clinician to thoughtfully self-reflect and merge the presented data with published literature strengthens the value of the process. Although this process encompassed only one clinician, only a small set of data, only descriptive statistics and a broad classification system, the quantification process provided concrete awareness of clinical experience.

Introduction/Background

[edit | edit source]

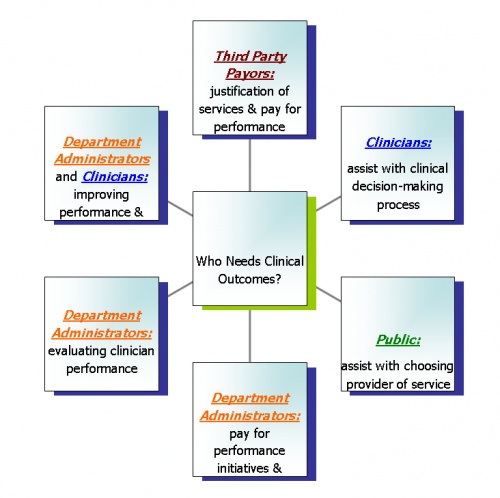

The relevance of clinical outcomes is becoming more prominent within the world of medicine. Third party payors are beginning to have higher expectations with the provision of physical therapy services.[1] A growing focus on outcomes and quality is becoming more prominent.[2] Evidence-based practice within the physical therapy profession requires the integration of individual clinical expertise and patient preferences with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.[3] Modification of processes to encompass the quantification of clinical experience, outcomes of care, and quality will meet the needs of involved stakeholders (Figure 1).

The Institute of Medicine defines quality as, “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and is consistent with current professional knowledge.”[4] A disconnect exists between this definition and the quality initiatives implemented within outpatient physical therapy settings. The current process in place generally consists of auditing records to ensure standardization of documentation, analyzing response time in meeting patient scheduling needs and analyzing satisfaction survey results.[5] The demands of the industry are continually evolving while the quality initiatives within the physical therapy industry have not necessarily evolved at the same pace as the needs of all the stakeholders, especially for the individual clinician.

Concrete awareness of clinical experience enhances the knowledge of a clinician’s effectiveness and initially provides a baseline for individual performance. Continual monitoring and analysis of clinical performance can lead to performance improvement. Because of the deficiency of outcome inclusion in quality initiatives, a physical therapist utilizes patient satisfaction survey and chart audit results combined with vague recollections to self-assess performance.

Self-assessment does not quantify clinical experience. From both quality and evidence-based perspectives, the common initiatives in outpatient physical therapy departments do not provide enough information for clinicians to quantify their clinical experience to assist in improving quality of care provided to the most important stakeholder – the patient.

Monitoring clinical performance is not a novel strategy for those in the academic setting. Students at the US Army-Baylor University Graduate Program in Physical Therapy experience the process involved in monitoring their clinical performance. Students are responsible for collecting a minimum data set which includes examination findings and outcome data for every patient with low back pain. After the clinical experience, students analyze and compare results to external literature. This particular academic setting has incorporated a quality performance improvement program within the clinical experience.

Because measuring and analyzing quality of care has often been neglected, clinicians are unaware of their actual clinical expertise. Without a quantification of clinical experience, clinicians cannot incorporate evidence based practice as defined because their clinical expertise is based on assumptions. Clinicians are not aware of their actual outcomes, provided with relevant information to support or alter clinical decision-making, held accountable for services provided or motivated to improve clinical performance. The purpose of this case report is to describe the development and implementation of a process that physical therapists may incorporate to quantify clinical performance in an outpatient physical therapy setting to assist with clinical decision-making.

Target Setting

[edit | edit source]

Clinicians in an outpatient orthopaedic setting need a process to monitor and quantify their clinical performance. The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice (the Guide)[6] has advocated clinicians measure and evaluate their clinical outcomes. The description of this process is limited to individual episodes of care. The process of quantifying clinical experience is not described. Although methods and results of outcome evaluation studies have been reported[7][8] these resources may be insufficient to guide the clinician to fully exploit outcome measurement in practice[9][10] and reflect on the effectiveness of interventions.[11]

Clinicians have options for quantifying clinical experience. One departmental option is to subscribe to a private database service for collection of outcome data, evaluation, and reporting of results.[12] The database service allows comparison of facilities and comparison of homogenous risk-adjusted populations. The database service has not been marketed to quantify individual clinical experience to enhance clinical decision-making. The analytical methods used by outcome database service providers are not available to non-participating clinicians or other stakeholders, except when studies are published evaluating subsets of their data.[7][8] Other options for clinicians include developing their own systematic approach to quantify clinical experience or relying on recollection of past experiences with patients. A comprehensive and inexpensive process utilizing common resources available to enable clinicians to integrate quantified clinical experience into evidence based practice has not been devised.

Development of the Process

[edit | edit source]

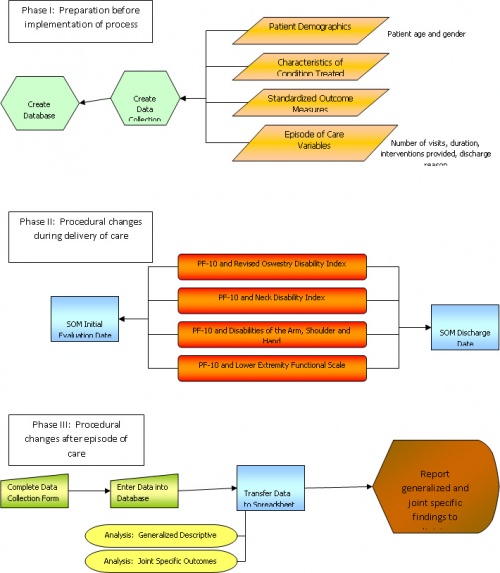

Three distinct phases occurred in the development of the process of quantifying clinical experience. Prior to implementation, a preparation phase occurred. The second phase of the process implemented procedural changes within the delivery of care. The last phase of the process incorporated procedural changes after the episode of care. Figure 2 highlights the details within each phase.

Phase I: Preparation

[edit | edit source]

Phase I was the most time intensive phase in the development of the process. Approximately 8-10 months was devoted to reviewing literature on standardized outcome measures (SOM); approximately 4 months was focused on reviewing literature on classification systems; approximately 2 months was allotted to determining the minimum data set; less than 1 month was required to create a data collection form; approximately 6 months was devoted to creating the database. Since some aspects of this phase occurred concurrently, approximately 16 months of preparation occurred prior to the implementation of the process.

Based on the patient population typically referred for services, a minimum data set was established for each patient with an orthopaedic condition. A data collection form standardized the data collection process (Appendix A). At the initiation of services, each patient was categorized into a preferred practice pattern referenced in The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice[13] and by body part to be treated. Data was collected to describe the duration of complaints for each patient. For this case study, acute was defined as 0-6 weeks from onset of symptoms; subacute was defined as > 6 week to 6 months; and chronic was defined as >6 months. Based on the typically referred patient population, the following SOM captured functional change: Revised Oswestry Disability Index (ODI),[14][15][16][17][18]Neck Disability Index (NDI)[19][20] Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)[21][22] and the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)[23][24] The Physical Functioning 10-item (PF-10)[25][26][18]aspect of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36)[27]captured health-related function. Table 1 highlights the psychometric properties of the SOM. The rationale for discharge/discontinuance of physical therapy services was also recorded. Four categories for discharge reason were related to clinical decisions. Four categories for discharge reason were related to patient issues. Table 2 identifies and describes the discharge reasons. Microsoft Access® 2000 served as the database.

|

Standardized Outcome Measure |

Scale |

Coefficient Alpha Values |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients |

Score Range |

Best Score |

MDC90 |

| ODI |

Likert |

0.82 to 0.90 |

0.88 to 0.94 |

0-100 |

0 |

10.5 |

| NDI |

Likert |

0.80 to .087 | 0.89 to 0.94 | 0-100 |

0 |

9.0 |

| DASH |

Likert |

0.96 to 0.97 | 0.92 to 0.96 | 0-100 |

0 |

10.7 |

| LEFS |

Likert |

0.93 to 0.96 | 0.85 to 0.94 | 0-80 |

80 |

9.0 |

| PF-10 |

Likert |

.93 |

.89 | 0-100 |

100 |

16.0 |

| Clinical Decisions |

|

| Discharge Reason |

Description |

| Goals Met | Successful outcome of episode of care |

| Discontinued – Minimal Progress/Plateau | Rate of progress was below anticipated rate such that expectancy for substantial positive change was within an unreasonable amount of time to justify skilled intervention |

| Referred Back to Physician | Further assessment or diagnostic testing recommended and recommendations communicated to referring physician with an end result of patient never returning for services |

| Services Inappropriate | Clinical findings did not indicate neuromusculoskeletal pathology or a change in condition occurred such that physical therapy services were not appropriate |

|

Patient issues |

|

| Discharge Reason |

Description |

| Never Returned | Patient never returned for physical therapy services |

| Insurance Issues | Patient chose to discontinue physical therapy services secondary to insurance issues |

| Poor Attendance | Patient had 3 no shows |

| Moved | Patient no longer able to attend for physical therapy services secondary to change in living location |

Phase II: Altering the Process Involved in the Delivery of Care

[edit | edit source]

Phase II was the least time intensive phase in the process. Although this phase was the least time intensive, an alteration in the normal process in the delivery of care required commitment from the clinician. During each episode of care, at minimum, the patient completed the PF-10 and an appropriate SOM at the initiation of services and at the termination of services. The physical therapist was responsible for determining the appropriate tool and for scoring both tools. Documentation was altered to consistently identify the preferred practice pattern, the affected joint of the body, stage of healing and functional scores at the initiation of physical therapy services.

Phase III: Procedural Changes after the Episode of Care

[edit | edit source]

Data entry and data analysis dominated Phase III. After each episode of care, the clinician completed the data collection form. The original patient chart was utilized to record all of the data manually on the data collection form. The data was then manually inputted into a record in Microsoft Access® 2000. After all the data for the defined time period was inputted, queries were performed in Microsoft Access® 2000. Table 3 outlines the information to query for the various reports generated. The columns of pertinent information from each query were then imported into Microsoft Excel® 2000 for both statistical analysis and chart generation. Microsoft Excel® 2000 did not calculate effect size. Since resources were limited, an online calculator[28] calculated effect size. Only two types of reports were created: a generalized descriptive summary report and a clinical outcome summary for each joint with 20 or more episodes of care with complete information.

| Query |

What to Query |

What Information is Learned |

| Completed Outcome Data |

All records with complete information |

Captures how consistently complete data collection occurred and the consistency in which the process was performed |

| Discharge Reason Data | Query each discharge reason for all records | Frequency of clinical decisions and patient issues |

| Distribution by Joint Data | Query each joint for all records | Frequency of clinical time spent treating individual joints |

| Distribution by Duration of Complaints | Query each onset of complaint category for all records | Frequency of when patients tend to begin physical therapy services after onset of complaint |

| Distribution by Gender | Query each gender for all records | Comparison of gender usage of physical therapy services |

| Distribution by Age | Query each defined age group for all records | Frequency of age group seeking physical therapy services |

| Query |

What to Query |

What Information is Learned |

| Functional Outcomes Data – All Completed Records |

Query for all records with complete information for specific joint | Compare initial level of function or amount of disability to discharge level of function or amount of disability for specific joint |

| Functional Outcomes Data for Goals Met and Minimal Progress/Plateau | Query both discharge reasons for all records with complete information for specific joint |

Compare initial level of function or amount of disability to discharge level of function or amount of disability with a level of clinical decision-making factored in the process for specific joint |

| Utilization Review Data – All Completed Records | Query for all records with complete information for specific joint | Analyze number of visits and duration of episode of care for specific joint |

| Utilization Review Data for Goals Met and Minimal Progress/Plateau |

Query both discharge reasons for all records with complete information for specific joint |

Analyze number of visits and duration of episode of care for specific joint with a level of clinical decision-making factored in the process for specific joint |

| Discharge Reason Data | Query each discharge reason for all records with complete information for specific joint |

Frequency of clinical decisions and patient issues for specific joint |

| Preferred Practice Pattern Data | Query each preferred practice pattern for all records with complete information for specific joint |

Frequency of preferred practice pattern for specific joint |

| Distribution by Duration of Complaints | Query each onset of complaint category for all records with complete information for specific joint | Frequency of when patients tend to begin physical therapy services after onset of complaint for specific joint |

| Distribution by Gender | Query each gender for all records with complete information for specific joint |

Comparison of gender usage of physical therapy services for specific joint |

| Distribution by Age | Query each defined age group for all records with complete information for specific joint |

Frequency of age group seeking physical therapy services for specific joint |

| Frequency of Treatment Units | Query for all records with complete information for specific joint |

Analyze number of units provided in each treatment category for specific joint |

Application of the Process

[edit | edit source]

Application of the process occurred with a sample of consecutive orthopaedic patients seen by the investigator. This study met the Health Insurance and Portability and Accountability Act requirements of the institution for disclosure of protected health information. To protect the privacy of patients, no personal health information was included in the analysis as required by the institution’s policy. Sparrow Health System Institutional Research Review Committee provided ethics approval for this case report. Signed consent to treatment was required from patients prior to the initiation of physical therapy services.

The process was implemented and data collected on all episodes of care with orthopaedic conditions from July 1, 2002 to April 20, 2004. All patients were referred by physicians. These clinical data were captured independent of submitted claims (claims would have excluded interventions lasting less than 8 minutes). Patients who were not capable of completing questionnaires did not complete SOM (e.g., those with dementia, those who were illiterate, or those who did not speak English). These patients were included as records without completed information.

With this particular case study, the physical therapist was responsible for all phases of the process. Administratively there was little to no support. The administrative barriers included: 1) a predominant belief that it would take too much time to incorporate SOM into each episode of care; 2) a belief that productivity would be reduced; 3) an assertation that it was not common practice to measure outcomes and 3) an assumption that all patients had successful outcomes with physical therapy. The process that was developed was only at the individual level for personal growth and was never incorporated into departmental policy and procedure.

Outcome

[edit | edit source]

The goal of this study was to develop and implement a process to quantify clinical experience to assist with clinical decision-making. The final reports created as result of the process provided the opportunity to enhance clinical outcome awareness by quantifying clinical experience. Appendix B concisely describes the population of the total 296 records. At a glance, the physical therapist can have a greater understanding of clinical decisions, the distribution of treatment to the various joints of the body and a quick synopsis of some patient characteristics. Appendices C, D, E, F and G summarize the clinical outcomes for the cervical spine, shoulder joint, lumbar spine, knee joint and foot/ankle joints respectively (for each with episodes of care of n>20). The results within the appendices represent records with completed data, unless stated otherwise.

Discussion

[edit | edit source]

Prior to implementing the administrative process, considerable thought, research and time occurred at the front end of the project. With this particular case report, the lack of administrative support was a large barrier. Because of the lack of administrative support, the development of the process to quantify clinical experience occurred in isolation of other therapists. The process developed may have been different if a team of individuals were brought together and if financial resources were available to improve the efficiency of the process. Besides the inclusion of additional physical therapists, a team consisting of individuals with a variety of skills outside of the physical therapy profession such as searching literature, creating databases, developing spreadsheets and designing reports would have strengthened the processes involved with quantifying clinical experience. The lack of support and financial resources reduced the potential opportunities and alternative avenues such that the process described was dependent on the current resources available to the physical therapist.

The described process once implemented begs to question whether it is a realistic expectation for therapists to utilize the specifics of this process. Phase III of the process entails tedious, monotonous and time intensive activities. Manually completing data collection forms, entering data, performing multiple queries, transferring query results to the appropriate worksheet in the spreadsheet, running calculations on the worksheet, creating charts on the worksheet, editing charts to create consistency of all charts within the various worksheets, working with multiple worksheets and then creating a final report consumes a large amount of time. Phase III of the process as described is too time intensive and costly for departmental administration to justify for a staff of physical therapists. A committed individual physical therapist with the same resources does have the opportunity to quantify clinical experience through the process described. A better resource for storing the data fields necessary to monitor individual clinical performance might be within an electronic medical record or through a subscription to a database service such as Focus on Therapeutic Outcomes, Inc. The capability to have automatic queries and reports generated would substantially improve efficiency, reduce the potential for manual errors and reduce costs associated with the time taken to manually input and analyze data.

Clinically, the implementation of the process at Phase II involved behavioral changes. In order to capture the necessary data, the physical therapist was required to remember to utilize the SOM. Based on the percentage of completed records (78.12%), it appears that the behavioral changes occurred at a reasonable rate considering utilizing SOM was a new component added to the day to day clinical operations. Compliance might have been greater if administration was supportive by having an outside party monitor the behavior through chart auditing.

Multiple limitations exist within this case report with the bulk of limitations within Phase III of the process. The therapist classified patients by the specific joint of the body to be treated during the initial visit. This classification system is problematic in hindsight. Upon reflection, a patient may initially complain of low back pain, but there were subgroups of patients that required, for example, hip mobilization. Sometimes a patient may have complaints of shoulder pain, but there were subgroups of patients that required, for example, cervical mobilizations. Patients that were classified into the lumbar spine or cervical spine categories were not further subgrouped into a treatment classification system. The risk of a broad classification system was the likelihood that no effect would be found upon analysis of data.

Another limitation to this case report is the lack of incorporating a method of risk adjustment. The process outlined does not allow for comparison to any risk-adjusted standards. Also, without risk adjustment, the clinician would be inequitably compared to peers in instances that patients were more challenging or more unhealthy than normal.

The greatest clinical value of the process was two fold. First, the implementation of SOM elevated awareness of each patient’s functional level. Treatment sessions potentially had a greater frequency of communication revolving around changes in function and included specific activities targeted to improve specific function. The tools were also very beneficial for concisely writing goals and seemed to enhance clinical decision-making by improving or substantiating clinical decisions. Second, the finalized summary reports gave a visual snapshot of clinical experience. Reviewing the summaries was a humbling experience, yet at the same time allowed for greater self-reflection to honestly question and critique clinical performance. The summaries indicated clinical strengths but could also target areas in which continuing education would be beneficial.

Clinically relevant questions can be derived through analyzing the reports. Appendix H outlines the potential self-reflection dialogue that could impact clinical performance. The discharge category for minimal progress/plateau requires self-reflection and potentially further research. It is unknown how or when a clinician determines that physical therapy services will not provide further benefit in a reasonable amount of time. This discharge category tends to have a greater amount of visits and could be an area that increases costs to stakeholders. Ethically, to whom are physical therapists aligned – the patient or the third party payor? What is a reasonable amount of progress or a guideline to follow that advocates for the patient yet also considers the cost of services? Further research to assist in determining which patients will respond and which patients do not respond to physical therapy services would be helpful in guiding clinical decision-making.

If the goal of quantifying clinical experience was to enhance clinical performance, then the next required step in the whole process would be defining a performance goal. Appendix E proved to be interesting. It was exciting to see good effect sizes and definite change in function, but it was disheartening to learn that the mean discharge disability was basically 24-30% with approximately 10-12 visits. The one component that could change in clinical performance was in the area of treatment units. Based on current literature, the best reported outcomes are achieved by a combination of manual therapy and exercise. The percentage of time spent providing manual therapy interventions was potentially low. An initial goal, hypothetically, would be to achieve an outcome of 12-15% disability within 8-10 visits for patients with complaints of lumbar pain with a discharge reason of goals met and minimal progress/plateau. To reach that goal would entail incorporating a higher frequency of manual therapy on the appropriate patients with lumbar pain.

The process described for monitoring clinical outcomes provided the desired result but was too laborious to be realistically implemented into a physical therapy department. Clinicians with very little resources may consider this process. Other options may be available that would provide the same useful clinical results by incorporating a different process. One aspect that would probably be consistent no matter the process would be the inclusion of SOM in Phase II. Realistically, implementation and incorporation of SOM into daily practice requires behavioral changes which may serve as a barrier to the process at the clinician level. The SOM could be a Phase I item to encourage and create the behavioral change before the whole process is even developed and implemented. Future plans include focusing clinical education on manual interventions for low back pain (what patients, when to provide manual intervention, what manual intervention to provide and how to provide the intervention). Data collection will begin again in the manner described to determine if the clinical performance goal could be met through a targeted plan to improve outcomes. Future research could focus on capturing variables of patients that respond to physical therapy intervention in comparison to patients that do not respond as favorably.

Even though this case report was substantially limited in available resources and funding, there is value within the summary reports. The clinical experience was quantified. The lack of awareness of quantified experience inhibits the ability to meet the needs of stakeholders. The first step to change and in improving quality should begin at the individual clinician level.

Presentations[edit | edit source]

<iframe src="https://www.slideshare.net/SelenaHorner/slideshelf" width="760px" height="570px" frameborder="0" marginwidth="0" marginheight="0" scrolling="no" style="border:none;" allowfullscreen webkitallowfullscreen mozallowfullscreen></iframe>

| 340|284}} | 340|284}} |

Appendices

[edit | edit source]

Appendix A: Functional Outcomes Data Collection Form

Appendix B: Generalized Descriptive Report Summary at a Glance

Appendix C: Summary Report of Clinical Outcomes for Cervical Spine

Appendix D: Summary Report of Clinical Outcomes for the Shoulder Joint

Appendix E: Summary Report of Clinical Outcomes for the Lumbar Spine

Appendix F: Summary Report of Clinical Outcomes for the Knee Joint

Appendix G: Summary Report of Clinical Outcomes for the Foot and Ankle Joints

Appendix H: Reflection on the Phases of the Process

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Correspondence from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan to all Independent Physical Therapists in Michigan. June 26, 2007Blue

- ↑ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Manual System. Pub 100-02 Medicare Benefit Policy Transmittal 63. December 29, 2006.

- ↑ Sackett DL. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- ↑ Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; 2001.

- ↑ Delitto A. Patient outcomes and clinical performance: parallel paths or inextricable links? Editorial. JOSPT. 2006;36(8):548-549.

- ↑ American Physical Therapy Association. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 2003.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Resnik L, Hart D. Using clinical outcomes to identify expert physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2003;83(11):990-1002.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jette D, Jette A. Physical therapy and health outcomes in patients with spinal impairments. Phys Ther. 1996;76(9):930-941, 942-945.

- ↑ Kirkness C, Korner-Bitensky N. Prevalence of outcome measure use by physiotherapists in the management of low back pain. Physiother Can. 2002;53(4):249-257.

- ↑ Kay T, Myers A, Huijbregts M. How far have we come since 1992? A comparative survey of physiotherapists' use of outcome measures. Physiother Can. 2001;53(4):268-275.

- ↑ Higgs J, Jones M. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. 2nd ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 2000.

- ↑ Focus on Therapeutic Outcomes Inc. website. Available at: http://www.fotoinc.com/research.htm Accessed 8/20/2007.

- ↑ American Physical Therapy Association. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association; 2003.

- ↑ Fairbank J, Couper J, Davies J, O'Brien J. The Oswestry Low Back Pain Questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271-272.

- ↑ Fairbank J, Pynsent P. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine. 2000;25:2940-2953.

- ↑ Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine. 2000;24:3115-3124.

- ↑ Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys Ther. 2001;80(2):776-788.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Davidson M, Keating JL. A comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsiveness. Phys Ther. 2002;82(1):8-24.

- ↑ Vernon H, Mior S. The Neck Disability Index: a study of reliability and validity. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics. Sep 1991;14(7):409-415.

- ↑ Stratford PW, Riddle DL, Binkley JM, et al. Using the Neck Disability Index to make decisions concerning individual patients. Physiother Can. 1999;51:107-112, 119.

- ↑ Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, et al. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. Journal of Hand Therapy. Apr-Jun 2001;14(2):128-146.

- ↑ McConnell S, Beaton D, Bombardier C. The DASH outcome measure user's manual: Institute for Work and Health; 1999.

- ↑ Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Watson J, Heath-Jones T. Validation of the LEFS on patients with total joint arthroplasty. Physiother Can. 2000;52:97-105.

- ↑ Binkley J, Stratford P, Lott S, et al. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development measurement properties and clinical application. Phys Ther. 1999;79:371-383.

- ↑ Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ et al. Assesing health related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine. 1995;20:1899-1908.

- ↑ McHorney C, Ware JE, Lu JFR, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item, Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;4(32):40-66.

- ↑ Ware JJ, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-83.

- ↑ Thalheimer W, Cook S. How to calculate effect sizes from published research articles: a simplified methodology. Retrieved August 25, 2007 from http://work-learning.com/effect_sizes.htm