A Case Study about Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Abstract[edit | edit source]

This fictional case study will investigate a 62 year old male diagnosed with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, otherwise known as PSP. This patient was referred to physiotherapy to help manage his symptoms. His main issues involved loss of balance, difficult swallowing, neck stiffness and difficulty controlling eye movements. This case study will investigate our fictional patient by providing an overview of PSP as a disorder, what is known about it, and then document the patient's experience with a Physiotherapist. This physiotherapist’s interaction with the patient will describe the initial assessment, including the subjective and objective findings, and problem list. Based off of this assessment, goals were developed as well as an evidence based treatment plan to help the patient achieve these goals. This treatment plan involved rhythm-based music gait training and traditional physiotherapy treatment to help manage and/or improve symptoms. On re-assessment after 12-weeks, it was found that the TUG score, BERG balance scale score, and PSP-QoL scores all slightly improved since the initial assessment.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy is a neurological disorder categorized as a Parkinson-plus disorder. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy can have a significant impact on your movement, such as eye movement, walking, balance, and extremity function. Additionally, it can also affect your cognition and behaviour.[1] People diagnosed with PSP typically are middle aged, however the actual cause of this disorder is not known. Upon diagnosis, the disease worsens quickly, and can turn severe within 5 years. Although PSP shares similar symptoms to those with Parkinson’s disease, there are some key differences such as axial rigidity, early onset eye movement dysfunction, and severe complications with speech and swallowing. An interesting difference between PSP and Parkinson's disease is that in individuals with PSP, they tend to fall backwards rather than forwards, which is typical in individuals with Parkinson's disease. The cause of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy is still unknown, however it is hypothesized that it could be caused by a combination of environmental factors and genetic causes. Treatment options are scarce for individuals with PSP, and little research supports the use of medications as an effective treatment technique.[2]

The purpose of this case study is to identify ways that physiotherapists can help diagnose individuals with PSP, and treat this condition using an evidence-based approach. Additionally, this case study will look at PSP 1-2 years after diagnosis and aim to treat patient specific goals for common PSP symptoms in this 1-2 year post-diagnosis time frame such as balance and gait, as well as go through a typical physiotherapist’s plan with a patient with PSP.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

William Quillesburg is a 62 year old male patient who was referred to our private clinic from a family physician to help manage William’s symptoms of PSP. William first began experiencing signs of PSP on June 20th 2021 while walking his dog one morning. That morning, William noticed his head shift backwards inadvertently and lost his balance which caused him to fall on his back. He did not think much of this, however over the next year he experienced similar falls while walking his dog. Furthermore, the frequency at which the falls started to occur increased. It was not until the morning of April 1st 2023 that he finally decided to seek help from the physician because over the course of a few months William developed inability to control his eyelids, neck stiffness and difficulty swallowing. William was diagnosed with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, one and a half years following the initial onset of symptoms. Due to the lack of evidence supporting the use of pharmaceuticals for treatment, William has been referred to physiotherapy by the physician to help manage his current symptoms and prevent further onset of this disease.

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

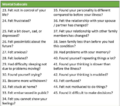

Subjective Findings[edit | edit source]

Past Medical History (PMHx)

One common comorbidity in patients with PSP that can be screened for is hypertension. William has had hypertension and high cholesterol levels for the past 7 years. No other significant medical history before PSP diagnosis. Poor response to L-Dopa. MRI identified hummingbird sign which highly suggests PSP[3].

Medications (Meds)

Lisinopril for hypertension (20 mg daily). Atorvastatin for high cholesterol (40 mg daily).

Health Habits (HH)

No history of smoking or drinking.

Family History (FHx)

His father had Alzheimer’s and his mother suffered a right MCA stroke in her 60s.

Social History (SHx)

Currently retired and lives alone. Used to play Bingo every second day at the local Bingo center (15-minute walk away) and walk his dog everyday, but not as able to anymore.

Functional History (FnHx)

Prior to the injury, was independent and had no difficulties with ADLs. No gait aids.

Current Functional Status (FnSt)

PSP affects his ability to walk and maintain balance, leading to falls. Uses a single He has developed some fear of falling and loss of confidence navigating more uneven terrain. Unable to get into and stand in shower without proprioceptive feedback; relies on handrail. Inhibited eyelid control leaves his eyes dry and often tired. Difficulty swallowing is starting to affect his ability to eat and socialize with others. Sleep is affected.

Objective Findings[edit | edit source]

Observation: presents with stooped posture and tilts head. Looks fatigued/anxious. Bradykinesia with movement as early as coming into the assessment room (i.e., taking off coat); also observed when completing PSP-RS.

Gait: reduced stride length and decreased swinging of arms bilaterally. Requires some assistance to maintain balance when walking. Recruits a wide base of support.

AROM/PROM:

Cervical ROM

- Flexion: 24°

- Extension: 30°

- Left side flexion: 16°

- Right side flexion: 15°

- Left rotation: 18°

- Right rotation: 21°

Shoulder ROM was limited bilaterally in external rotation (41°) and flexion (62°). ROM at other UE and LE joints WNL. AROM and PROM were equally limited.

Neurological testing:

- Dermatomes and myotomes intact bilaterally. Slump was positive bilaterally.

| Reflex Test | Left | Right |

| Babinski | + | + |

| Oppenheimer | + | + |

| Clonus | - | - |

| Biceps (C6) | 3 | 3 |

| Triceps (C7) | 2 | 2 |

| Patellar (L3-L4) | 2 | 2 |

| Achilles | 2 | 2 |

MMT: bilateral weakness (3-) in knee extension. Bilateral weakness (4-) in hip flexion and ankle dorsiflexion.

TUG: required 23 seconds to complete.

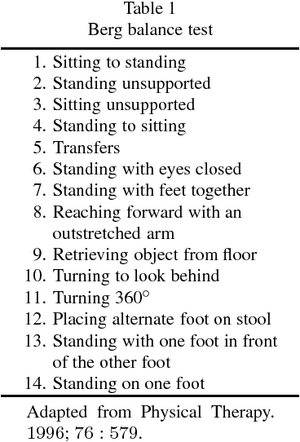

Berg Balance Scale: 35/56. Difficulty maintaining balance with feet together and eyes closed. Requires support in tandem stance.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale (PSP-RS): scored 44/100 on the PSP-RS.

| History | 10/24 |

| Mentation | 5/16 |

| Bulbar | 3/8 |

| Ocular motor | 3/16 |

| Limb motor | 9/16 |

| Gait and midline | 14/20 |

PSP-QoL[4]: 71/100

Clinical Hypothesis[edit | edit source]

William McQuabbie is a 62 year-old male experiencing impaired balance leading to frequent falls which disrupt his ability to walk his dog and get to the local bingo center. He demonstrates symmetrical axial rigidity, muscle stiffness associated with dysphagia, issues with gait, signs of upper motor neuron lesion, and starts to face some mental challenges.

Prognostically, the disease is progressive with most surviving up to 5-8 years after diagnosis[6]. However, he is starting from a good baseline as an active individual who walked his dog everyday previously.

Problem List

- Impaired balance leading to falls. Berg Balance Score of 35/56, indicating moderate falls risk.

- Decreased ambulation tolerance. TUG requires 23 s to complete.

- Social isolation and increased withdrawal from hobbies like playing Bingo and walking his dog. 71/100 on PSP-QoL score which could be improved.

Intervention[edit | edit source]

While understanding that William presented with PSP symptoms such as impaired balance leading to falls, axial rigidity, and muscle stiffness, it is important to note that William was not considered “severe” and can follow similar treatment guidelines to Idiopathic Parkinson’s disorder as certain treatment techniques have shown to positively benefit both disorders.

Our intervention approach aimed to be client-centered by creating specific short-term and long-term goals based on William’s current phenotype and problem list, while maintaining an evidence-based intervention style. It was important to attempt to get William back to doing his regular routine within limits, such as walking his dog, and participating in his bingo sessions. With these factors in mind, an intervention program was developed.

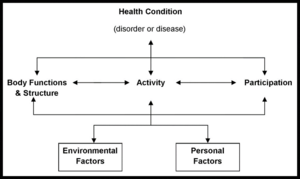

The intervention program involved short-term and long-term goals for the following ICF domains:

- Body Function and Structure

- Participation

- Activities

The goals for each domain are listed below:

Short-term Goal #1 for Body Function and Structure:[edit | edit source]

William will score at least 38 on the Berg Balance Scale after 4 weeks of Physiotherapy.

Long-term Goal #1 for Body Function and Structure:[edit | edit source]

William will be able to walk his dog again with no falls, and the assistance of a mobility aid, after 5 months of physiotherapy.

Short-term Goal #2 for Participation:[edit | edit source]

William will be able to maintain at least 71/100 on the PSP-QoL scale after 3 weeks of Physiotherapy.

Long-term Goal #2 for Participation:[edit | edit source]

William will be able to navigate to weekly bingo sessions, play independently, and return home safely using his mobility aid after 5 months of Physiotherapy.

Short-term Goal #3 for Activities:[edit | edit source]

William will be able to complete the TUG test in 19 seconds within 4 weeks of Physiotherapy treatment.

Long-term Goal #3 for Activities:[edit | edit source]

William will be able to safely travel 400m with his mobility aid, with no complications, after 12 months of Physiotherapy treatment.

Treatment:[edit | edit source]

First, we fitted William with a quad cane so that we can reduce the falls risk present, while maximizing mobility for daily activity. Second, we recommended that William ideally attended physiotherapy sessions 3 times a week, in order to have the best chance to maintain or improve his current presentation. The core of our treatment involves music-cueing to help facilitate effective gait technique. This form of treatment was conducted in conjunction with regular physiotherapy treatment techniques in order to provide William with the best outcome possible.[8] Music-cued exercise training has been shown to be an effective and engaging way for individuals with PSP to improve aerobic endurance and retrain gait patterns[9]. Furthermore, it can prove to be an optimal technique for individuals with PSP because the part of the brain responsible for rhythm, are not associated with the basal ganglia which is heavily affected in individuals with PSP.[10]

Physical Therapy sessions consisted of:

- Warm-up (10 minutes)

- Lower limb strengthening (20 minutes)

- Gait training with music (20 minutes)

Warm-up (10 minutes - Choose exercise based on patient’s current presentation)[edit | edit source]

- Single leg balance each leg 2x20 sec

- Right + Left torso rotation 2x10

- Quad & hamstring stretch 1x20 until feeling of discomfort

- Neck left + right rotation 1x10

- Neck flexion and extensions 1x10

- Heel tapping, hand clapping 1x10

Strengthening plan (20 minutes)[edit | edit source]

- Scapular squeezes 2x8

- Supported calf raises 2x8

- Knee flexion & extension 3x10 each leg

- Supported sit to stands 3x (to simulate the TUG)

Gait training with music (30 minutes)[edit | edit source]

- Patients are given a choice of music genre selection ranging from country to pop to classical music, in hopes to increase satisfaction and adherence to the program. Each song choice presented contains a cadence that can be adjusted to the patient's ability level.

- When the music begins, patients listen to the music beats/rhythms and are instructed to perform specific movements on cue with the beat/rhythm heard in the song playing, that relate to walking, or build up to walking techniques, such as knee raises or arm swings.

- Each session, the music can be adjusted to fit the ability of William, and the specific movements performed can be progressed or regress in difficulty.

The Use of Innovative Technology for Individuals with PSP[edit | edit source]

Innovative technology is being used more frequently as we begin to better understand Progressive Supranuclear Palsy as a disease, and continue to determine the best options for treatment. One example of an innovative technology used for patients with PSP in recent history is the use of gaming systems to facilitate increase in motor control, awareness and improvement in gait patterns. In the specific case of William, the use of this gaming system, specifically the XBox Kinect, several activity-based games could be chosen, therefore tailoring the treatment to the patient.[12] Furthermore, each activity based game can be adjusted in difficulty, and potentially mimic functional tasks based on the goals of the patient. In William’s case, we could use XBox Kinect to improve gait, improve cardiovascular health, and potentially aim to get him walking his dog again, through virtual dog walking games. However, it is important to note that there are some challenges to incorporating these types of technological tools into intervention plans. First, it is important to understand that innovative technology is still a relatively new approach to treatment in individuals with PSP, therefore for patients who are considered elderly, it may present a challenge for them to understand treatment and adhere to the program in general. Furthermore, the platform of XBox Kinect has recently stopped receiving support from its original developer for the development of its product. Although XBox Kinect can facilitate physical activity in a variety of different populations, there is question on how tailored an intervention program can be, especially in clinical practice, if a decreased number of games and updates are being made. Regardless, these challenges can be mitigated by providing an educational seminar to patients interested in XBox Kinect therapy so that they can better understand their treatment options and the technology itself. Additionally, there are other gaming systems that support exercise-based treatment that are consistently being updated. It is possible that if a clinical environment does not deem XBox Kinect to be suitable for use in clinical practice, another platform such as Playstation VR can be used.

Outcome[edit | edit source]

Outcomes assessed at follow-up 12 weeks:[edit | edit source]

BERG Balance Scale: 40/56 (significantly improved from initial assessment but still displays a medium falls risk)[13]

Upon assessment, the patient has the ability to complete independent sit to stands using hands and transfer safely with definite need of hands. Although, the patient obtains a score of 2 while standing unsupported with perturbations like eyes closed, arm reaching, turning left and right while standing, and standing unsupported with one foot. These perturbations make gait more challenging for the patient especially when they are presented with these perturbations during the swing phase. Bradykinesia was also noted during the performed tasks.

TUG score: 18 seconds. During the test, the patient displayed bradykinesia while walking. Additionally, the patient relied on their upper extremities while standing up to initiate performing this test. The score indicates that the individual may need some assistance, potentially a gait aid. In order to provide the patient with some stability, it is recommended to provide the patient with a quad cane.[15]

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating scale:

Total Score: 47/100

- History 10/24

- Mentation 5/16

- Bulbar 3/8

- Ocular motor 4/16

- Limb motor 10/16

- Gait and midline 15/20

This score increased by 3 points compared to the initial assessment. Due to the progressive nature of the disease, it is typical to obtain a higher score compared to the patients initial assessment. Compensatory strategies in functional activities such as gait, balance, transfers, and ADLs can be used when addressing future interventions for this patient[17].

PSP-QoL: 64/100

Psychometric Properties of Outcome Measures:[edit | edit source]

PSP-RS: Inter-rater reliability is high and there is a moderate level of validity.[18]

Studies have shown that the BERG displays moderate to high validity when compared to other functional tasks and measurements[19]. Both TUG and BERG are highly reliable measures for secondary parkinsonism disorders[20]. Specifically TUG has high test-retest reliability[21]. Although, it is important to note that the BERG has a ceiling effect [22], but would still be sufficient for determining what sub categories of balance the patient experiences the most difficulty in. TUG shows high validity in geriatric populations which is applicable to our patient[23].

PSP-QoL: high reliability and acceptable level of validity from supporting factor analysis and interscale correlation.[24]

Outcome Summary and Discharge notes[edit | edit source]

William demonstrated clinically significant outcomes in his TUG and BERG score 12 weeks post physiotherapy intervention. Throughout the physiotherapy intervention, William displayed significant improvements in his balance throughout a variety of functional tasks which was displayed through the Berg score. He also showed significant improvement in his TUG score from initial assessment to post, reducing his risk of falls. It is important to note that even though he has improved his score on both of these measures, he is still at a moderate fall risk. Additionally, his PSP- RS score slightly increased due to the progressive nature of the disease. The patient also obtained a lower PSP-QoL score post 12 weeks, indicating better quality of life when performing everyday tasks. Overall, the patient felt more in control when experiencing perturbations, which may have led to a fall in the past. The gait training with music allowed William to adjust his speed, gait rhythm, cadence, and power output from lower extremities and upper extremities, in order to meet the different external cues and perturbations provided. Additionally, William felt like he had greater strength to maintain his balance over the course of the program. Whereas, before he felt a sense of fear to participate in exercise programs due to his falls risk. Additionally, due to the nature of PSP being a progressive disease, it may be a challenge to further improve his PSP-RS score. According to research, on average patients have an increased PSP-RS score of about 10 points[25]. This is due to the deteriorating progressive course of the disease. Thus, we hypothesize that even with physiotherapy intervention his PSP-RS score may continue to worsen, but may occur at a slower rate. Although physiotherapy may help slow the rate of negative effects, it is not an end all solution for individuals with PSP. Overall, William states that he has increased confidence when ambulating and when performing transfers. He also reported less fall frequency, and increased awareness of when a potential fall may occur and increased understanding of what may cause a potential fall. William has become more aware of potential perturbations that may lead to a loss of balance. Also, William has displayed appropriate strategies to bring his base of support back to midline when experiencing a perturbation. William displays adequate ankle and hip recovery strategies when presented with anterior-posterior perturbations, while occasionally using his upper extremities and the side step recovery strategy when presented with lateral perturbations. Therefore, this displays the importance of the strengthening program, which target these major muscle groups. The referrals mentioned below have been sent in order to further improve Williams quality of life and safety. We feel confident to discharge William from our program due to significant improvements in balance, gait, safety, motivation, and compensatory strategies. Although, we still recommend William to visit a physiotherapist at least once a month to monitor his functional capacity and to provide recommendations and compensatory strategies as needed[26]. Additionally, a quad cane is recommended upon discharge since the patient is still a falls risk. This provides the patient with a greater sense of support, potentially encouraging him to continue his active interventions as it limits the fear of falling.

Intervention Plan Modification if Adverse Events are Reported:[edit | edit source]

If the client reports an adverse event, the intervention plan can be modified by adjusting the FITT principles. Frequency can be adjusted throughout the day, allowing for increased amount of bouts but deceased length of bouts throughout the day. For example, this can be done by having William perform one 10 minute strengthening session in the morning and one 10 minute strengthening session in the afternoon. This can help to overcome the effects of fatigue, which may improve performance regarding gait, balance and endurance. Additionally, if the patient is experiencing symptoms of fatigue, profuse sweating, increased heart rate, RPE, dizziness, or lightheadedness then it should be considered to regress the gait training with music intervention. The patient can regress the intensity by selecting a slower paced song. Breaks can be implemented throughout the session as well. The fatigue factor can be accounted for by having the patient still perform the dynamic tasks while seated, such as marching while seated according to the rhythmical patterns produced from the music. If adverse events still continue, it is important to note your patient's limits and dismiss the session for the day. For future reference, note the FITT parameters and patient symptoms in your charting that resulted in the discontinued session.

Referrals[edit | edit source]

Occupational therapist: This referral is sent on behalf of the physiotherapy circle of care for the patient William Quillesburg. William would benefit from an in-home assessment. The patient is a falls risk, thus he would benefit from equipment such as stability bars, that can make daily functional tasks safer and easier to accomplish.

Speech language pathologist: This referral is sent on behalf of the physiotherapy circle of care for the patient William Quillesburg to address concerns regarding swallowing difficulties.

Social worker: This referral is sent on behalf of the physiotherapy circle of care for the patient William Quillesburg. Due to progressively emerging health complications, the patient would benefit from assistance to explore potential future living accommodation options, along with any funding that he may be eligible for.

Discussion[edit | edit source]

This case demonstrates the reality of living with PSP for many individuals. Even though William has received intensive physiotherapy treatment interventions, it is difficult to reverse the effects of a progressive neurological disorder. Unlike many musculoskeletal issues where physiotherapy interventions can help bring one's function back to baseline, the same could not be said for progressive neurological conditions such as PSP. On average, individuals with PSP live about 5-7 years after they have been diagnosed due to the progressive nature of the disease[28]. Therefore, it is crucial that as physiotherapists, we consider the course of the disease and form a rehabilitation plan that aims to provide safe, effective, and functional compensatory strategies so that individuals with PSP can still be as independent as possible, rather than trying to provide recovery strategies that are non-realistic. It is still important to provide recovery approaches for these patients when they are safe and functional. Also, it is imperative to form realistic goals that are meaningful to the patient while taking into account all aspects of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model. It is important to consider an interdisciplinary approach when working with patients with PSP, as they may benefit from many other services that address their swallowing, social and environmental issues. Overall, this case discussed a scenario of a male older adult who was early on in his diagnosis of PSP, which was about 2 years post onset. Thus, he is more likely to display more significant improvements in his BERG and TUG compared to cases where individuals are at the more severe stages of PSP. Hence, the intervention plan used in this case study was directed towards addressing earlier stages of PSP. It is important to note that different stages display different needs and strategies in rehabilitation, and recovery or improvement varies in each stage. Regarding William, we hypothesize that the disease will increase in severity over the course of the years. As the disease progresses, the intervention plan may need to be modified as well.

Self-Study Questions[edit | edit source]

Q1: Which of the following statements regarding the case study about Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) is false?

- PSP is a neurological disorder that affects movement and balance

- Medication is proven to be an effective treatment

- One distinguishing symptom for PSP from Parkinson’s Disorder is the presence of axial rigidity

- PSP can turn severe as quick as 5 years from initial symptom onset

Q2: Which of the following was NOT used as an outcome measure in the case study?

- PSP-RS

- TUG

- Hoehn and Yahr Scale

- Berg Balance Scale

Q3: Which of the following is not a subscale of the Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale?

- Ocular motor

- Limb motor

- Gait and midline

- ADL capability

Answers: Q1 = 2, Q2 = 3, Q3 = 4.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Agarwal S, Gilbert R. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. [Updated 2022 Apr 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526098/

- ↑ Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Internet]. www.ninds.nih.gov. Available from: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/progressive-supranuclear-palsy-psp

- ↑ Verma R, Gupta M. Hummingbird sign in progressive supranuclear palsy. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2012 Nov;32(6):663–4.

- ↑ Hall DA, Forjaz MJ, Golbe LI, Litvan I, Payan CAM, Goetz CG, et al. Scales to Assess Clinical Features of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: MDS Task Force Report. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice. 2015 May 22;2(2):127–34.

- ↑ Pantelyat A, Higginbotham L, Rosenthal L, Lanham D, Nesspor V, AlSalihi M, et al. Association of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Quality of Life Scale. Neurodegenerative Diseases. 2020;20(4):139–46.

- ↑ Barer Y, Chodick G, Cohen R, Grabarnik-John M, Ye X, Zamudio J, et al. Epidemiology of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Real World Data from the Second Largest Health Plan in Israel. Brain Sciences. 2022 Aug 24;12(9):1126.

- ↑ Days Bariatric Quad Cane [Internet]. www.performancehealth.ca. [cited 2023 May 13]. Available from: https://www.performancehealth.ca/days-bariatric-quad-canes

- ↑ Salgado S, Williams N, Kotian R, Salgado M. An Evidence-Based Exercise Regimen for Patients with Mild to Moderate Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sciences [Internet]. 2013 Jan 16;3(1):87–100. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4061827/

- ↑ 1. Slade SC, Finkelstein DI, McGinley JL, Morris ME. Exercise and physical activity for people with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: a systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2019 Sep 27;34(1):026921551987723.

- ↑ Wittwer JE, Winbolt M, Morris ME. A Home-Based, Music-Cued Movement Program Is Feasible and May Improve Gait in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Frontiers in Neurology [Internet]. 2019 Feb 19;10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2019.00116/full

- ↑ Hakansson NA, Kesar T, Reisman D, Binder-Macleod S, Higginson JS. Effects of Fast Functional Electrical Stimulation Gait Training on Mechanical Recovery in Poststroke Gait. Artificial Organs. 2011 Mar;35(3):217–20.

- ↑ Seamon B, DeFranco M, Thigpen M. Use of the Xbox Kinect virtual gaming system to improve gait, postural control and cognitive awareness in an individual with Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2016 Mar 23;39(7):721–6.

- ↑ Donoghue D, Stokes E. How much change is true change? The minimum detectable change of the Berg Balance Scale in elderly people. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine [Internet]. 2009;41(5):343–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19363567/

- ↑ Quan, Zwick D, Rochelle A, Choksi A, Domowicz J. Evaluation and treatment of balance in the elderly : A review of the efficacy of the Berg Balance Test and Tai Chi [Internet]. www.semanticscholar.org. 2000 [cited 2023 May 14]. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Evaluation-and-treatment-of-balance-in-the-elderly-Quan-Zwick/94073b87a6916093a3b300fe4982d9e257016f37

- ↑ Barry E, Galvin R, Keogh C, Horgan F, Fahey T. Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta- analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2014 Feb 1;14(1).

- ↑ Timed Up and Go (TUG) [Internet]. Strokengine. Available from: https://strokengine.ca/en/assessments/timed-up-and-go-tug/

- ↑ Nonnekes J, Ružicka E, Nieuwboer A, Hallett M, Fasano A, Bloem BR. Compensation Strategies for Gait Impairments in Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurology. 2019 Jun 1;76(6):718.

- ↑ Golbe LI, Ohman-Strickland PA. A clinical rating scale for progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. 2007 Apr 23;130(6):1552–65.

- ↑ Mollinedo I, Cancela JM. Evaluation of the psychometric properties and clinical applications of the Timed Up and Go test in Parkinson disease: a systematic review. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2020 Aug 25;16(4):302–12.

- ↑ Mollinedo I, Cancela JM. Evaluation of the psychometric properties and clinical applications of the Timed Up and Go test in Parkinson disease: a systematic review. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2020 Aug 25;16(4):302–12.

- ↑ Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L. Age- and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: Six-Minute Walk Test, Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up & Go Test, and gait speeds. Physical therapy [Internet]. 2002;82(2):128–37. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11856064

- ↑ Dale ML, Prewitt AL, Harker GR, McBarron GE, Mancini M. Perspective: Balance Assessments in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Lessons Learned. Frontiers in Neurology [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Mar 23];13:801291. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35153996/

- ↑ Mollinedo I, Cancela JM. Evaluation of the psychometric properties and clinical applications of the Timed Up and Go test in Parkinson disease: a systematic review. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2020 Aug 25;16(4):302–12.

- ↑ Schrag A, Selai C, Quinn N, Lees A, Litvan I, Lang A, et al. Measuring quality of life in PSP: The PSP-QoL. Neurology. 2006 Jul 10;67(1):39–44.

- ↑ Hewer S, Varley S, Boxer AL, Paul E, Williams DR. Minimal clinically important worsening on the progressive supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale. Movement Disorders. 2016 Oct;31(10):1574–7.

- ↑ Nonnekes J, Ružicka E, Nieuwboer A, Hallett M, Fasano A, Bloem BR. Compensation Strategies for Gait Impairments in Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurology. 2019 Jun 1;76(6):718.

- ↑ What is ICF? [Internet]. icfeducation.org. Available from: https://icfeducation.org/what-is-icf

- ↑ Armstrong MJ, Castellani RJ, Reich SG. “Rapidly” Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice [Internet]. 2014 Apr [cited 2023 Jan 31];1(1):70–2. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6182982/