Valgus stress to ulnar collateral ligament

Top Contributors - Wendy Snyders, Rachael Lowe, Admin, Kim Jackson and George Prudden

Top Contributors - Wendy Snyders, Rachael Lowe, Admin, Kim Jackson and George Prudden

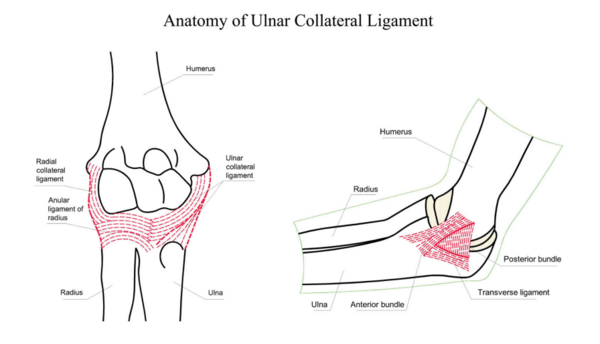

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The ulna collateral ligament (UCL) consists of three bundles - the anterior oblique ligament/bundle (AOL), the posterior oblique ligament/bundle (POL) and the transverse ligament (which unites AOL and POL)[1][2]. Of the three bundles, the AOL is the strongest and provides significant restraint to valgus force when the elbow is between 30 and 120 degrees flexion. The UCL originates at the anterior-inferior aspect of the medial epicondyle of the humerus and it inserts at the sublime tubercle (the proximal aspect of the ulna)[1][2] . Its main functions are to stabilise the elbow joint and to resist valgus loads[1].

The UCL stabilises the elbow joint by slowing down elbow extension during throwing's deceleration phase and by generating a varus torque, counterbalancing the valgus force[1].

The proximal UCL is well vascularised and gets its blood supply from the recurrent flexor or pronator artery[3]. The distal aspect of the UCL is relatively hypovascularised[3].

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

UCL injuries are usually due to chronic repetitive load rather than an acute injury[2][3] with tears typically occuring proximally[3]. Poor stabilisation together with repetitive near-failure tensile loads can lead to microtrauma, weaking the AOL and potentially leading to rupture or instability[1]. Acute ruptures typically occur during traumatic dislocations of the elbow, often associated with articular fractures[4]. These injuries typically occur in javelin throwers, football quarterbacks and softball players[5].

Complete rupture of the AOL prevents countering of valgus stress during the acceleration phase of throwing, making forceful overhead throwing nearly impossible[1].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Acute or sub-acute phase:

- Medial elbow pain[3][5]

- Medial swelling [2]

- Point tenderness along the ligament[2][5]

- No range-of-motion limitation (ROM)[2]

- Throwers may often recall feeling or hearing a "pop"[3][5].

- Ulna-nerve compression signs and symptoms - usually sensory[3].

Chronic:

Athletes may also present for ulnar nerve compression symptoms, which are usually sensory[3].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Imaging

- Stress x-rays can be taken and compared to the opposite side to see if there is increased medial joint gapping. This may helpful in aiding the diagnosis of complete UCL tears[3]. X-rays are also helpful to show any associated avulsion fractures, osteophytes, loose bodies or osteochondral lesion

- Ultrasound can also be used to aid the diagnosis of UCL tears[2][3]. It can be used as a dynamic test to assess integrity, thickness and joint gapping with valgus stress[3]. It has been shown to be cost-effective and efficient[5] but is user-dependant[3].

- MRI is helpful in distinguishing between partial and complete tears[2][3]. A 6-part classification system by Ramkumar et al can be used to guide treatment decisions. It defines the tear location and distinguishes between complete and tears[3].

Stress test

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Cubital tunnel syndrome or ulnar neuropathy[3]

- Flexor-pronator muscle strain[3]

- Snapping medial triceps[3]

- Osteochondral lesions[3]

- Cervical radiculopathy[3]

- Medial epicondyle apophysitis[3]

- Olecranon stress fracture[3]

- Valgus extension overload syndrome[3]

- Medial epicondyle avulsion[3]

- Elbow arthritis[3]

Management[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to the differential diagnosis of this condition

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Zaremski JL, Vincent KR, Vincent HK. Elbow ulnar collateral ligament: injury, treatment options, and recovery in overhead throwing athletes. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2019 Sep 1;18(9):338-45.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Biz C, Crimi A, Belluzzi E, Maschio N, Baracco R, Volpin A, Ruggieri P. Conservative versus surgical management of elbow medial ulnar collateral ligament injury: a systematic review. Orthopaedic Surgery. 2019 Dec;11(6):974-84.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 Gehrman MD, Grandizio LC. Elbow ulnar collateral ligament injuries in throwing athletes: diagnosis and management. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 2022 Mar 1;47(3):266-73.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Biz C, Crimi A, Belluzzi E, Maschio N, Baracco R, Volpin A, Ruggieri P. Conservative versus surgical management of elbow medial ulnar collateral ligament injury: a systematic review. Orthopaedic Surgery. 2019 Dec;11(6):974-84.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Sutterer BJ, Boettcher BJ, Payne JM, Camp CL, Sellon JL. The Role of Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Elbow Medial Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries in Throwing Athletes. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2022 Nov 12:1-2.

References