Stork Test: Difference between revisions

m (editing) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

<br></div> | <br></div> | ||

[[Category:Special_Tests]] | |||

Revision as of 11:03, 17 March 2018

Original Editors - Lauren Trehout

Top Contributors - Jetse De Proft, Lauren Trehout, Yvonne Yap, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Adam Vallely Farrell, Kim Jackson, Maram Salem, Rachael Lowe, George Prudden, Tarina van der Stockt, Wanda van Niekerk and Ahmed M Diab

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

University’s Library (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) and databases: Pubmed, Pedro, Sciencedirect and google.

Keywords: stork test, Gillet test, sacroiliac joint technique, rucklauf test

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Sacroiliac joint (SIJ) mobility tests are a large number of clinical test to asses movement or asymmetry of the SIJ.10 (LOE 2B) Sacroiliac joint region dysfunction is a term frequently used to describe the cause of pain in or around the region of the joint that is presumed to be due to misalignment or abnormal movement of the SI-joints.4 (LOE 2B)

The assessment of the Stork test involves palpation of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS).

The therapist places one thumb directly on the PSIS and the other thumb is placed medial to the PSIS, on the sacral base. Ask the patient to raise one knee up, that the hip and knee are flexed to 90°. Assess the posterior rotation of the innominate on the side of the lifted knee. Then ask the patient to raise the other knee up while assessing the anterior rotation of the innominate on single leg support side. The direction of the bone motion is palpated as the contralateral foot is lifted off the ground.6 (LOE 5)

Various studies show that men are less mobile than women and elderly people starting from the age of 65 are less mobile than younger people.23

Women who gave birth are more mobile with an increase in contra nutation of the pelvic joint than women who have not.17. (LOE 2A)

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The sacroiliac joints are essential for effective load transfer between the spine and the lower extremities. The sacrum, pelvis and spine-, are functionally interrelated through muscles, fascia and ligamentous interconnections.

This joint is the largest axial joint in our body and has an average surface of 17, 5 cm2, 14. (LOE 2B, 3A)

The SIJ is uniquely composed of a synovial joint, which permits very little, to no movement and a diarthrodial joint or free moveable joint. The capsular portion of the sacrum is made up of hyaline cartilage (diarthrosis). The capsular portion of the ilium consists of fibrocartilage, which provides considerable internal stability. 13 (LOE 3A) Other characteristics include strong weight bearing, paired C-shaped joints. 14 (LOE 3A)

Essentially, the SIJ is encased in a capsule that has a smooth anterior wall but there is an absence of a rudimentary posterior capsule. Hence the SI ligaments are more developed dorsally, functioning as a connecting band between the sacrum and ilia. These ligaments are represented in figure 1. The sacroiliac ligament complex prevents a great mobility of the sacrum between the two ilia. The ligaments of the SI ligament complex are weaker in women than in men, allowing the ability to give birth.16 (LOE 2A)

Low back pain at the level of the SIJ is not always linked to force closure, but can also be linked to form closure with the passive structures. There is some evidence18 (LOE 3A) that the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament should not be overlooked in causes of low back pain.

The sacrotuberous ligaments are directly connected to the long head of the biceps femoris, the piriformis and the gluteus maximus, thus they can have an influence on the SIJ mobility.16 (LOE 2A) There are 32 other muscles, which attach on the sacrum and can be found in: SACRO-ILIAC JOINT MUSCLES

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Purpose[edit | edit source]

The relationship between the SIJ and low back pain has been a subject of debate. Some researchers regard SIJ pain as a major contributor to the problem of low back pain while others regard it as unimportant or irrelevant. It is nowadays generally accepted that about 13 % of patients with chronic low back pain have the origin of pain confirmed as the SIJ.2 (LOE 2B)

There are two clinical perspectives to consider. The first is the SIJ as a load-transferring mechanical junction between the pelvis and the spine that may cause either the SIJ or other structures to produce painful stimuli. The second perspective considers the SIJ as a source of pain.

The first perspective proposes that the joint is malfunctioning. Therefore the word dysfunction is commenly used to encapsulate the complexity of abberations believed to occur. The evidence favoring that mechanical SIJ dysfunctions are related to the experience of back and referred pain is less than convincing. The range of motion in the SIJ is small, less than 4° of rotation and up to 1,6 mm of translation. Hence in patients presumed to have an SIJ source of pain it is difficult and doubtful to found differences in range of motion between the symptomatic and asymptomatic sides.2(LOE 2B)

Due to the poor reliability and validity of many SIJ mobility assesment tests. And with an increased understanding of the role of the pelvis in load transfer has shifted the focus of clinical assessment procedures for SIJ function from SIJ mobility testing to functional assessment procedures that test the ability of the pelvis to maintain stability during load transfer between the spine and the lower limbs.2

An investigation of motion between the innominate bone and the sacrum on the side of single-leg support during a standing hip flexion movement revealed that the innominate bone on the side of single-leg support rotated posteriorly relative to the sacrum in subjects who were healthy. This pattern was altered reliably in the presence of PGP. Here the innominate bone rotated anteriorly relative to the sacrum, which was an indication of a failure of the self-bracing mechanism to maintain the SIJ in its closed pack position. Therefore the Stork test may be a useful test for clinical evaluation of a subject's ability to stabilize intrapelvic motion.2 (LOE 2B)

Technique[edit | edit source]

The assessment of the Stork test involves palpation of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). The therapist places one thumb directly on the PSIS and the other thumb is placed medial to the PSIS, on the sacral base. Ask the patient to raise one knee up, that the hip and knee are flexed to 90°. Assess the posterior rotation of the innominate on the side of the lifted knee. Then ask the patient to raise the other knee up while assessing the anterior rotation of the innominate on single leg support side. The direction of the bone motion is palpated as the contralateral foot is lifted off the ground.6 (LOE 5)

In a normally functioning pelvis, the pelvis of the side being palpated should rotate posteriorly, causing the PSIS to drop or move inferiorly. The test is positive when the PSIS on the ipsilateral side (same side of the body) of the knee flexion moves minimally in the inferior direction or doesn’t move. A positive test is an indication of sacroiliac joint hypomobility.19 (LOE 1A)

The test is negative when the SI-joint is not blocked on the side of the lifted leg, the ilium of the leg will rotate in dorso-caudal direction. The PSIS will move a fraction below the PSIS of the supporting leg in dorso-caudal direction.

Hungerford et al. concluded that the ability of the physiotherapist to reliably palpate and recognize an altered pattern of intrapelvic motion during Stork Test on the support side was substantiated. The ability to distinguish between no relative movement and anterior rotation of the innominate bone during a load-bearing task was good. Although further research is needed to determine the validity of this test for detecting pelvic girdle dysfunction2(LOE 2B).

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Several studies concluded that not a single test but a cluster of tests should be used to confirm diagnosis. Other sacroiliac pain provocation tests to evaluate the mobility of the sacroiliac joint are the Distraction test, Compression test, Thigh thrust test, Gaenslen’s test and Sacral thrust test. 21 ( LOE 1A)

A positive Stork test (Gillet test), combined with other positive sacroiliac mobility tests, indicates an valid impairment of mobility of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ). Springing tests, by means of which a passive mobility ("joint play") is being tested, are most valuable in dysfunction diagnostics22. ;The clinical use of these clusters however has yet to been validated .Multiple studies confirm that these tests have no significance to determine SIK dysfunction nor pain.17,11,9 .1 study determined that the stork test, together with the examniation of irritation points and irritation points during functinal testing could asses SIJ dysfunction.Therefore, the physical therapy management for this dysfunction was Mobilizing techniques without impulse as well as manipulative techniques with high-velocity impulses were applied to resolve the dysfunction 5. (LOE 2B).

The thigh thrust test, compression test, and three or more positive stressing tests showed discriminative power for diagnosing SI joint pain. 3 of 5 must be positive (Thigh Thrust, Compression, Gaenslen, FABER, Distraction). 1 of 3 positive results must be Thigh Thrust or Compression.23.

Manual High-Velocity-Low-Amplitude (HVLA) manipulation is an efficient method of treatment for patients with sacroiliac dysfunction. In a study7 (LOE 1B), improvements in pain (VAS-scale) and function were detected 2 days and 1 month after a single session. No consensus is found about the underlying mechanisms of treating SIJ dysfunctions. A few plausible explanations for improvements are increased ROM, normalization of muscle tone and disrupting articular adhesions.

The following is a description of the HVLA manipulation technique used in the LOE 1B study. The patient is supine and the therapist stands contralateral to the side which is to be manipulated (e.g. right) (Fig. 2). The patient is passively moved into side bending toward the side to be manipulated. The patient should inter-lock their fingers behind their head. The therapist passively rotates the patient, and then delivers a quick thrust to the Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS) in a posterior and inferior direction.3(LOE 1B)

Examination

[edit | edit source]

Reliability

[edit | edit source]

1) The outcomes of individual mobility tests, including the Gillet’s test, are not reliable in diagnosing SIJ dysfunction11(LOE 1A)

2) The outcomes of individual mobility tests, including the Gillet’s test, are not valid in diagnosing SIJ dysfunction12(LOE 1A)

3) A cluster of mobility tests and provocation tests have an average to high reliability in the assessment of the SIJ 1(LOE2B)

4) A single manual HVLA manipulation session is proven to reduce pain and mobility impairment for people suffering from SIJ dysfunction1(LOE 2B)

5) Physical therapists can recognize an altered pattern of intrapelvic motion during the Stork Test. Physical therapists can distinguish between no relative movement and anterior rotation of the innominate bone during a Stork test17(LOE 2A).

6) According to a study, The Gillet test, as performed in this study, does not appear to be reliable.20 (LOE 1B)

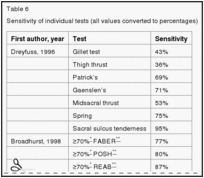

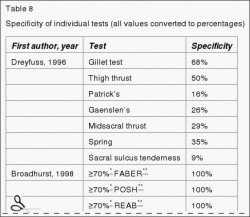

The Diagnostic Accuracy of the Gillet test (stork test) is described below:

Sensitivity is the proportion of people with a positive test result who have the target disorder, essentially true positives.21 (LOE 1A)

Specificity is the proportion of people with a negative test result who do not have the target disorder, essentially true negatives.21 (LOE 1A)

Visual example of test[edit | edit source]

Kinetic Test of SI Joint: Stork Test

How to assess motion of the Sacroiliac Joint - Stork / Gillett test

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Pubmed, Pedro, Web of Knowledge

Recent Related Research (from pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Feed goes here!!|

References[edit | edit source]

1. Arab AM, Abdollahi I, Joghataei MT, Golafshani Z, Kazemnejad A.,”Inter- and intra-examiner reliability of single and composites of selected motion palpation and pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint.”, Man Ther. 2009 Apr;14(2):213-21. (1B)

2. Barbara A Hungerford et al., “Evaluation of the ability of physical therapists to palpate intrapelvic motion with the stork test on the support side.”, Journal of American Physical therapy Association, 2007; 87:879-887. (2B)

3. Cleland, J., Fritz, J., et al., “Comparison of the effectiveness of three manual physical therapy techniques in a subgroup of patients with low back pain who satisfy a clinical prediction rule: a randomized clinical trial.” Spine (2009)34 (25), 2720. (1B)

4. Daniel L Riddle, Janet K Freburger and North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network, “Evaluation of the presence of sacroiliac joint region dysfunction using a combination of test: a multicenter intertester reliability study.” , 2002. Journal of the amercian Physical Therapy association, 2002; 87:879-887. (2B)

5. Galm R, Fröhling M, Rittmeister M, Schmitt E., “Sacroiliac joint dysfunction in patients with imaging-proven lumbar disc herniation.”, Eur Spine J. 1998;7(6):450-3. (1B)

6. Jeffrey Gross, Wiley-Blackwell, Musculoskeletal Examination 3rd edition, 2009, p. 114.

7. Kamali F, Shokri E., “The effect of two manipulative therapy techniques and their outcome in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome.”, Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 2012 16, 29e35. (1B)

8. Kamali F, Shokri E., “The effect of two manipulative therapy techniques and their outcome in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome.”, 2007; 87:879-887.PHYS THER. (3B)

9. Riddle DL, Freburger JK., “Evaluation of the presence of sacroiliac joint region dysfunction using a combination of tests: a multicenter intertester reliability study.”, PHYS THER., 2002 Aug; 82(8):772-782. (2B)

10. Sturesson, Bengt Md, Uden Alf MD, PhD, Vleeming, Andry PhD., “A radiostereometric analysisof movements of the sacroiliac joints during the standing hip flexion test.”, Spine, 2000; 25(2):214. (2B)

11. van der Wurff P, Hagmeijer RH, Meyne W., “Clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint. A systematic methodological review. Part 1: Reliability.”, Man Ther. 2000 Feb;5(1):30-6. (1A)

12. van der Wurff P, Hagmeijer RH, Meyne W., “Clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint. A systematic methodological review. Part 1: Reliability.”, Manual Therapy, 2000; 5(2):89±96. (1A)

13. A. Vleeming;M. D. Schuenke;A. T. Masi;J. E. Carreiro;L. Danneels and F. H. Willard. The sacroiliac joint: an overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications; Journal of Anatomy Volume 221, Issue 6, pages 537–567, December 2012. (LOE 3A)

14. Cohen S., Steven P., Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis and treatment, IARS, November 2005, volume 101, issue 5, pp 1440-1453 (LOE 3A)

15. Bernard TN, Cassidy JD. The sacroiliac syndrome. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. In: Frymoyer JW, ed. The adult spine: principles and practice. New York: Raven, 1991;2107–30. (LOE 2A)

16. Calvillo O., Skaribas I., Turnispeed J., Anatomy and pathophysiology of the SIJ, current science, 2000 (LOE 2A)

17. Hungerford B, Evaluation of the ability of physical therapists to palpate intrapelvic motion with the Stork test on the support side; Physical Therapy; 2007; Jul;87(7):879-87. (LOE 2A)

18. Vleeming A, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Hammudoghlu D, Stoeckart R, Snijders CJ, Mens JM. The function of the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament: its implication for understanding low back pain. Spine 1996;21:556-62 (LOE 3A)

19. Magee DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment. 5th ed. St. Louis: Saunders, 2008. (LOE 1A)

20. Wilco Meijne, Katinka van Neerbos, Geert Aufdemkampe, Peter van der Wurff d, Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability of the Gillet test, Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics Volume 22, Issue 1, Pages 4–9, January 1999. (LOE 1B)

21. KJ Stuber. Specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values of clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint: a systematic review of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2007; 51(1): 30-41 ( LOE 1A)

22. Grgić V.; The sacroiliac joint dysfunction: clinical manifestations, diagnostics and manual therapy; Lijec Vjesn. 2005 Jan-Feb;127(1-2):30-5. (LOE 3A)

23. Karolina M. Szadek, et al.; Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review.; The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society 10, no. 4 (April 2009): 354-368. (LOE 1A)

24. © 2015 Davis et al. Mobility predicts change in older adults’ health-related quality of life: evidence from a Vancouver falls prevention prospective cohort study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2015