Stork Test: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Ahmed M Diab (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== | == Purpose == | ||

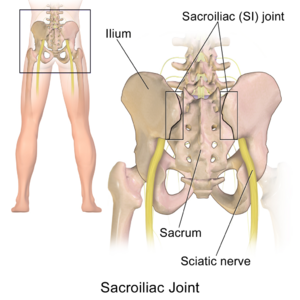

[[File:Sacroiliac Joint human.png|thumb]] | |||

The [[sacroiliac Joint|sacroiliac joint]] (SIJ) is the joint connection between the spine and the pelvis. It can easily be palpated in the low back region in the posterior pelvic area. The sacroiliac joint accounts for 10-27% of the causes of low back pain or buttock pain<ref>Nejati P, Safarcherati A, Karimi F. Effectiveness of exercise therapy and manipulation on sacroiliac joint dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. Pain physician. 2019;22(1):53-61.</ref>, with a common complaint of localized pain at joint itself. SIJ dysfunction refers to misalignment or abnormal movement of the SIJ, which can cause pain in or around the SIJ.<ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">Daniel L Riddle, Janet K Freburger and North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network, “Evaluation of the presence of sacroiliac joint region dysfunction using a combination of test: a multicenter intertester reliability study.” , 2002. Journal of the amercian Physical Therapy association, 2002; 87:879-887. (2B)</span></ref> | |||

The Stork Test, also known as the Gillet Test, the Step Test, and the One-Legged Stance Test, assesses the movement of the SIJ between the innominate and sacrum through the clinician's palpation of the [[Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome|posterior superior iliac spine]] (PSIS). This may be a useful test for clinical evaluation of a subject's ability to stabilize intrapelvic motion.<ref name=":1">Barbara A Hungerford et al., “Evaluation of the ability of physical therapists to palpate intrapelvic motion with the stork test on the support side.”, Journal of American Physical therapy Association, 2007; 87:879-887. (2B)</ref> | |||

== | == Technique == | ||

<div> | |||

To perform the Stork Test, begin by standing behind the patient and palpate the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) on the right and left side of the hip. The person is asked to stand on one leg while flexing the opposite knee and bring the knee closer to the chest.<ref>Ribeiro RP, Guerrero FG, Camargo EN, Beraldo LM, Candotti CT. Validity and Reliability of Palpatory Clinical Tests of Sacroiliac Joint Mobility: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2021 May;44(4):307-18.</ref> The test is then repeated on the other side and compared bilaterally<ref name="null">Dutton M. Orthopaedic examination, evaluation, and intervention. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008.</ref><ref name="null2">Konin J, Wiksten D, Isear J, Brader H. Special test for orthopedic examination. New Jersey: Slack, 2002.</ref>. The examiner should compare each side for quality and amplitude of movement<ref name="Lee">Lee D. The pelvic girdle: an approach to the examination and treatment of the lumbo-pelvic-hip region. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.</ref>. | |||

In a normal functioning pelvis, the PSIS should move caudally, or inferiorly, when the leg is flexed towards the chest. If the PSIS remains level or moves superiorly, this indicates a positive test and warrants further examination of the SIJ. A positive test is an indication of sacroiliac joint hypomobility.<ref>Magee DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment. 5th ed. St. Louis: Saunders, 2008. (LOE 1A)</ref> {{#ev:youtube|pvsDU6IJoSc|400}}<ref>PhysioTutors. The Gillet Test for SI-Joint Dysfunction. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvhvKXnXAac[last accessed 19/10/2023]</ref> | |||

< | == Evidence == | ||

<div> | |||

<br>The | The range of motion in the SIJ is small, less than 4° of rotation and up to 1.6 mm of translation. There is a minimal palpable difference between the symptomatic and asymptomatic sides for patient with presumed SIJ pain due to the minimal movement the joint allows.<ref name=":1" />Rather than use one test during an examination, it is recommended that a cluster of tests be used to confirm a diagnosis. The recommended [[Sacroiliac Joint Special Test Cluster|SIJ Test Item Cluster]] are:<ref>KJ Stuber. Specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values of clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint: a systematic review of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2007; 51(1): 30-41 ( LOE 1A)</ref> | ||

# Distraction Test | |||

# Compression Test | |||

# Thigh Thrust Test | |||

# Gaenslen’s Test | |||

# Sacral Thrust Test | |||

In order to confirm a diagnosis of SIJ pain, 3 of 5 of the tests must be positive. At least 1 of the 3 positive results must be the Thigh Thrust Test or the Compression Test.<ref>Karolina M. Szadek, et al.; Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review.; The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society 10, no. 4 (April 2009): 354-368. (LOE 1A)</ref><br>A positive Stork Test, combined with other positive sacroiliac mobility tests, indicates a valid impairment of mobility of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ). Springing tests, by means of which a passive mobility ("joint play") is being tested, are most valuable in dysfunction diagnostics<ref>Grgić V.; The sacroiliac joint dysfunction: clinical manifestations, diagnostics and manual therapy; Lijec Vjesn. 2005 Jan-Feb;127(1-2):30-5. (LOE 3A)</ref>. However, the clinical use of these clusters has yet to been validated. Multiple studies confirm that these tests have no significance to determine SIJ dysfunction nor pain.<ref name=":0">Hungerford B, Evaluation of the ability of physical therapists to palpate intrapelvic motion with the Stork test on the support side; Physical Therapy; 2007; Jul;87(7):879-87. (LOE 2A)</ref><ref name=":2">van der Wurff P, Hagmeijer RH, Meyne W., “Clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint. A systematic methodological review. Part 1: Reliability.”, Man Ther. 2000 Feb;5(1):30-6. (1A)</ref><ref>Riddle DL, Freburger JK., “Evaluation of the presence of sacroiliac joint region dysfunction using a combination of tests: a multicenter intertester reliability study.”, PHYS THER., 2002 Aug; 82(8):772-782. (2B)</ref>. | |||

</div> | |||

== Reliability == | |||

<div> | <div> | ||

The Stork Test should not be the sole test used to diagnose SIJ dysfunction. <ref name=":2" /><ref>Wilco Meijne, Katinka van Neerbos, Geert Aufdemkampe, Peter van der Wurff d, Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability of the Gillet test, Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics Volume 22, Issue 1, Pages 4–9, January 1999. (LOE 1B)</ref>The Stork Test demonstrates high reliability when a group of mobility and provocation tests are performed along with it.<ref>Arab AM, Abdollahi I, Joghataei MT, Golafshani Z, Kazemnejad A.,”Inter- and intra-examiner reliability of single and composites of selected motion palpation and pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint.”, Man Ther. 2009 Apr;14(2):213-21. (1B)</ref> When used alone, the Stork Test's reliability is low (0.22) and is not recommended to be used individually.<ref>Dreyfuss P, Dreyer S, Griffin J, Hoffman J, Walsh N. Positive sacroiliac screening test in asymptomatic adults. Spine. 1994;19(10):1138-1143.</ref> | |||

= | |||

The | |||

< | |||

A meta analysis on intra-rater reliability reported the Stork test to have moderate to good agreement (κ = 0.46)<ref>Ribeiro RP, Guerrero FG, Camargo EN, Beraldo LM, Candotti CT. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2021.01.001. Validity and Reliability of Palpatory Clinical Tests of Sacroiliac Joint Mobility: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis]. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 2021; 44(4):307-318. <nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2021.01.001</nowiki>.</ref> Hungerford et al. concluded that the ability of the physiotherapist to reliably palpate and recognize an altered pattern of intrapelvic motion during Stork Test on the support side was substantiated. The ability to distinguish between no relative movement and anterior rotation of the innominate bone during a load-bearing task was good. The validity of the test is 55.%.<ref>Stuber KJ. Specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values of clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint: a systematic review of the literature. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2007 Mar;51(1):30.</ref> <br> | |||

< | |||

< | |||

</ | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

</div> | |||

<references /> | |||

< | |||

[[Category:Special_Tests]] | [[Category:Special_Tests]] | ||

[[Category:Sacroiliac Examination]] | |||

[[Category:Sacroiliac Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Sports Medicine]] | |||

[[Category:Athlete Assessment]] | |||

[[Category:Pelvis]] | |||

[[Category:Pelvis - Special Tests]] | |||

[[Category:Vrije Universiteit Brussel Project]] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:18, 10 March 2024

Original Editors - Lauren Trehout

Top Contributors - Jetse De Proft, Lauren Trehout, Yvonne Yap, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Adam Vallely Farrell, Kim Jackson, Maram Salem, Rachael Lowe, Wanda van Niekerk, Ahmed M Diab, George Prudden and Tarina van der Stockt

Purpose[edit | edit source]

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is the joint connection between the spine and the pelvis. It can easily be palpated in the low back region in the posterior pelvic area. The sacroiliac joint accounts for 10-27% of the causes of low back pain or buttock pain[1], with a common complaint of localized pain at joint itself. SIJ dysfunction refers to misalignment or abnormal movement of the SIJ, which can cause pain in or around the SIJ.[2]

The Stork Test, also known as the Gillet Test, the Step Test, and the One-Legged Stance Test, assesses the movement of the SIJ between the innominate and sacrum through the clinician's palpation of the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). This may be a useful test for clinical evaluation of a subject's ability to stabilize intrapelvic motion.[3]

Technique[edit | edit source]

To perform the Stork Test, begin by standing behind the patient and palpate the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) on the right and left side of the hip. The person is asked to stand on one leg while flexing the opposite knee and bring the knee closer to the chest.[4] The test is then repeated on the other side and compared bilaterally[5][6]. The examiner should compare each side for quality and amplitude of movement[7].

In a normal functioning pelvis, the PSIS should move caudally, or inferiorly, when the leg is flexed towards the chest. If the PSIS remains level or moves superiorly, this indicates a positive test and warrants further examination of the SIJ. A positive test is an indication of sacroiliac joint hypomobility.[8] [9]Evidence[edit | edit source]

The range of motion in the SIJ is small, less than 4° of rotation and up to 1.6 mm of translation. There is a minimal palpable difference between the symptomatic and asymptomatic sides for patient with presumed SIJ pain due to the minimal movement the joint allows.[3]Rather than use one test during an examination, it is recommended that a cluster of tests be used to confirm a diagnosis. The recommended SIJ Test Item Cluster are:[10]

- Distraction Test

- Compression Test

- Thigh Thrust Test

- Gaenslen’s Test

- Sacral Thrust Test

In order to confirm a diagnosis of SIJ pain, 3 of 5 of the tests must be positive. At least 1 of the 3 positive results must be the Thigh Thrust Test or the Compression Test.[11]

A positive Stork Test, combined with other positive sacroiliac mobility tests, indicates a valid impairment of mobility of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ). Springing tests, by means of which a passive mobility ("joint play") is being tested, are most valuable in dysfunction diagnostics[12]. However, the clinical use of these clusters has yet to been validated. Multiple studies confirm that these tests have no significance to determine SIJ dysfunction nor pain.[13][14][15].

Reliability[edit | edit source]

The Stork Test should not be the sole test used to diagnose SIJ dysfunction. [14][16]The Stork Test demonstrates high reliability when a group of mobility and provocation tests are performed along with it.[17] When used alone, the Stork Test's reliability is low (0.22) and is not recommended to be used individually.[18]

A meta analysis on intra-rater reliability reported the Stork test to have moderate to good agreement (κ = 0.46)[19] Hungerford et al. concluded that the ability of the physiotherapist to reliably palpate and recognize an altered pattern of intrapelvic motion during Stork Test on the support side was substantiated. The ability to distinguish between no relative movement and anterior rotation of the innominate bone during a load-bearing task was good. The validity of the test is 55.%.[20]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Nejati P, Safarcherati A, Karimi F. Effectiveness of exercise therapy and manipulation on sacroiliac joint dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. Pain physician. 2019;22(1):53-61.

- ↑ Daniel L Riddle, Janet K Freburger and North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network, “Evaluation of the presence of sacroiliac joint region dysfunction using a combination of test: a multicenter intertester reliability study.” , 2002. Journal of the amercian Physical Therapy association, 2002; 87:879-887. (2B)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Barbara A Hungerford et al., “Evaluation of the ability of physical therapists to palpate intrapelvic motion with the stork test on the support side.”, Journal of American Physical therapy Association, 2007; 87:879-887. (2B)

- ↑ Ribeiro RP, Guerrero FG, Camargo EN, Beraldo LM, Candotti CT. Validity and Reliability of Palpatory Clinical Tests of Sacroiliac Joint Mobility: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2021 May;44(4):307-18.

- ↑ Dutton M. Orthopaedic examination, evaluation, and intervention. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008.

- ↑ Konin J, Wiksten D, Isear J, Brader H. Special test for orthopedic examination. New Jersey: Slack, 2002.

- ↑ Lee D. The pelvic girdle: an approach to the examination and treatment of the lumbo-pelvic-hip region. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

- ↑ Magee DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment. 5th ed. St. Louis: Saunders, 2008. (LOE 1A)

- ↑ PhysioTutors. The Gillet Test for SI-Joint Dysfunction. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dvhvKXnXAac[last accessed 19/10/2023]

- ↑ KJ Stuber. Specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values of clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint: a systematic review of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2007; 51(1): 30-41 ( LOE 1A)

- ↑ Karolina M. Szadek, et al.; Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review.; The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society 10, no. 4 (April 2009): 354-368. (LOE 1A)

- ↑ Grgić V.; The sacroiliac joint dysfunction: clinical manifestations, diagnostics and manual therapy; Lijec Vjesn. 2005 Jan-Feb;127(1-2):30-5. (LOE 3A)

- ↑ Hungerford B, Evaluation of the ability of physical therapists to palpate intrapelvic motion with the Stork test on the support side; Physical Therapy; 2007; Jul;87(7):879-87. (LOE 2A)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 van der Wurff P, Hagmeijer RH, Meyne W., “Clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint. A systematic methodological review. Part 1: Reliability.”, Man Ther. 2000 Feb;5(1):30-6. (1A)

- ↑ Riddle DL, Freburger JK., “Evaluation of the presence of sacroiliac joint region dysfunction using a combination of tests: a multicenter intertester reliability study.”, PHYS THER., 2002 Aug; 82(8):772-782. (2B)

- ↑ Wilco Meijne, Katinka van Neerbos, Geert Aufdemkampe, Peter van der Wurff d, Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability of the Gillet test, Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics Volume 22, Issue 1, Pages 4–9, January 1999. (LOE 1B)

- ↑ Arab AM, Abdollahi I, Joghataei MT, Golafshani Z, Kazemnejad A.,”Inter- and intra-examiner reliability of single and composites of selected motion palpation and pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint.”, Man Ther. 2009 Apr;14(2):213-21. (1B)

- ↑ Dreyfuss P, Dreyer S, Griffin J, Hoffman J, Walsh N. Positive sacroiliac screening test in asymptomatic adults. Spine. 1994;19(10):1138-1143.

- ↑ Ribeiro RP, Guerrero FG, Camargo EN, Beraldo LM, Candotti CT. Validity and Reliability of Palpatory Clinical Tests of Sacroiliac Joint Mobility: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 2021; 44(4):307-318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2021.01.001.

- ↑ Stuber KJ. Specificity, sensitivity, and predictive values of clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint: a systematic review of the literature. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2007 Mar;51(1):30.