Spondylolisthesis

Original Editors - Margo De Mesmaeker

Top Contributors - Maëlle Cormond, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Evi Peeters, Margo De Mesmaeker, Kim Jackson, Admin, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Shaimaa Eldib, Kenneth de Becker, Lucinda hampton, Rachael Lowe, Mike Myracle, Evan Thomas, Carlos De Coster, Johnathan Fahrner, Aminat Abolade, Mariam Hashem, Shreya Pavaskar, Camille Linussio, Claire Knott, Rucha Gadgil, Laura Ritchie, Jess Bell, Kirenga Bamurange Liliane and Scott Buxton

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

PubMed. Keywords: spondylolisthesis, anatomy, physical therapy, physiotherapy, low back pain, exercise therapy, therapeutic exercise, spondylolisthesis review, medical management/treatment, fusion, surgery

Filters: 5 years, human.

Web of Science. Keywords: spondylolisthesis, diagnosis, differential diagnosis. Filters: article and review, English, rehabilitation (category), orthopedics (category)

Definition / Description[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis is defined as a translation of one vertebra over the adjacent caudal vertebra. This can be a translation in the anterior (anterolisthesis) or posterior direction (retrolysthesis) or, in more serious cases, anterior-caudal direction.[1] (LE: 2A) [2] (LE: 1A)

It is classified on the basis of etiology into the following five types by Wiltse: Dysplastic (congenital), isthmic, degenerative, traumatic, and pathologic spondylolisthesis.[1] (LE: 2A)

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

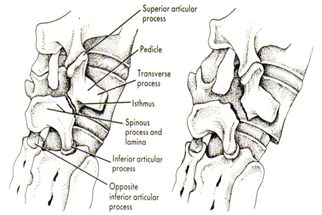

The main anatomical structure involved is the fractured pars interarticularis of the lumbar vertebrae [4] (LE: 3A). In addition, ligamentous structures, including the iliolumbar ligament, between L5 and the sacrum, are stronger than those between L4 and L5, by which the vertebral slip commonly develops in L4 [5] (LE: 3B).

Isthmic or spondylolytic spondylolisthesis (type II) appears mainly at the lumbosacral level. (L5-S1) [6] (LE: 2B). It is characterized by high lordosis angles and lordotic wedging of the affected vertebra (L5) and very high L4-5 intervertebral disc wedging [7] (LE: 3B) [8] (LE: 2B).

Degenerative spondylolisthesis (type III) appears mainly at the L4-5 level and is characterized by a significant constriction of the cauda equina, combined with a diminished cross-sectional area of the vertebral canal, thickening and buckling of the ligamentum flavum and hypertrophy of adjacent facet joints [6] (LE: 2B).

Figure 1: Scottie dog [9] (LE :1B).

Epidemiology / Etiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of spondylolisthesis varies considerably depending on ethnicity, sex, and sports activity [10] (LE: 5). Several epidemiological studies have revealed that the incidence of symptomatic listhesis in Caucasian populations varies from 4 to 6% [11] (LE: 2A) [12] (LE: 2A), but rises as high as 26% in secluded Eskimo populations [13] (LE: 2A) and varies from 19 to 69% among first-degree relatives of the affected patients [14] (LE: 2A).

Depending on the studies conducted, this percentage can vary. [15] (LE:2B) [16] (LE: 2B) [17] (LE: 2B) [18] (LE: 2B) [19](LE: 2B)

Type I: Congenital spondylolisthesis. Symptoms usually develop during the adolescent growth period [10] (LE: 5).

Type II: Isthmic spondylolisthesis. It is typically considered as a pediatric condition [20] (LE: 1A). Saraste (1987) demonstrated that the onset of symptoms tends to occur after childhood, with a mean age at presentation of 20 years [21] (LE: 2B).

Type III: Degenerative spondylolisthesis. In this type the L4–L5 vertebral space is affected 6 to 9 times more commonly than other spinal levels. [22] (LE: 2B) [10] (LE: 5). It is also a common condition in the elderly (>50 years). The main causes are:

- Disc degeneration;

- Facet joint arthrosis;

- Malfunction of the ligamentous stabilizing component;

- Ineffectual muscular stabilization.

[23] (LE: 3A) [24] (LE: 5) [25] (LE: 1A)

Potential risk factors are:

- Increasing age;

- Female sex;

- Pregnancies;

- African-American ethnicity;

- Generalized joint laxity

- Anatomical predisposition (sagitally oriented facet joints, hyperlordosis, high pelvic incidence)

[26] (LE: 3A)

Characteristics / Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

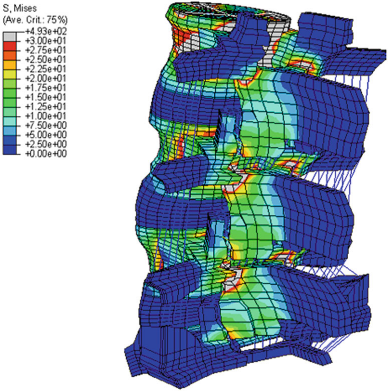

Figure 2: Highest stress during various lumbar motions is found at the pars interarticularis, as shown in a threedimensional finite element moedel [27] (LE: 2B)

Symptoms and findings in spondylolisthesis are:

- Low back pain;

- Pain the legs;

- Dull pain, typically situated in the lumbosacral region after exercise, especially with an extension of the lumbar spine;

- Diminished ROM (spine);

- Tense hamstrings;

- Neurological symptoms (possible evolution towards cauda equine syndrome)

Patients usually report that their symptoms vary in function of mechanical loads (such as in going from supine to erect position) and pain frequently worsens over the course of the day (figure 3). Radiation into the posterolateral thighs is also common and is independent of neurologic signs and symptoms. The pain could be diffuse in the lower extremities, involving the L5 and/or L4 roots unilaterally or bilaterally [28] (LE: 5).

In addition to these findings, each type of spondylolythesis has its own characteristics

Spondylolisthesis can occur together with other disorders and seems to have a link with some of them:

Several studies support a positive association between spina bifida occulta and spondylolysthesis [31] (LE: 2A). This high association may not be due to mechanical factors but to genetich factors [29] (LE: 2C).

- Cerebral palsy [32] (LE: 2B);

A number of studies proved the association between cerebral palsy and spondylolysthesis, certainly in athetoid cerebral palsy (60%) [32] (LE:2B).

Ogilvie and Sherman reported a 50% incidence of spondylolysthesis in 18 patients with Scheuermann’s disease [33] (LE: 2B). Greene et al. found spondylolysthesis (grade I or II) at L5-S1 in 32% of patients with Scheuermann’s disease [34](LE: 2B).

- Scoliosis [31] (LE: 2A).

Fisk et al. reported that the incidence in 539 patients with ideopatic scoliosis was 6.2%, which corresponded to that found in the general population [35] (LE: 2B). But the relation between scoliosis and spondylolysthesis has not been clarified [31] (LE:2A).

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

- Spondylolysis [36] (LE: 1A) [37] (LE: 4)

- Metastatic disease [6] (LE: 2B)

- Low back pain [38] (LE: 1C)

- Osteoarthritis [38] (LE: 1C) http://www.physio-pedia.com/Osteoarthritis

- Neuroforaminal stenosis [38] (LE: 1C)

- Spinal stenosis [38] (LE: 1C)

Diagnostic Procedures / Examination[edit | edit source]

History

Specific questions should be asked referring to:

- Pain [38] (LE: 1C)

o Location

o Severity

o Duration

o Quality (for example: tingling, burning,.. sensations)

o Exacerbating factors

o Alleviating factors

- Leisure activities [38] (LE: 1C)

- Occupational risks [38] (LE: 1C)

- Pain changes throughout day: difference morning compared to evening/night?

Imaging

Most commonly used clinical imaging is X-ray, CT and MRI. [36] (LE: 1A)

X-ray

Overall X-ray of the spine and lumbosacral X-ray are seen as the golden standard for diagnosis [38] (LE: 1C)

There are multiple views used with the most common one being the anteroposterior, lateral and oblique views. [36] (LE: 1A) [9] (LE: 1B) [6] (LE: 2B) Multiple characteristics can be seen, such as the degree of the slip or the slip angle. The most prominent sign remains the defect of the pars interarticularis, or more commonly named the broken collar or neck of the “Scottie Dog” [9] (LE: 1B)

CT and MRI

CT and MRI, which give an accurate localization and a better illustration of the lesion (35) (LE: 1A), are taken when one of the following signs are present: [6] (LE: 2B)

- Significant and progressing neurologic claudication [6] (LE: 2B) [38] (LE: 1C)

- Radiculopathies and the clinical suspicion that another condition may be causative [6] (LE: 2B) [38] (LE: 1C)

- Bladder or bowel complaints [6] (LE: 2B)

- Metastatic disease [38] (LE: 1C)

And used for one of the following reasons:

- Evaluating an atypical presentation including pre-lysis [9] (LE: 1B)

- Determining the condition of the intervertebral disc [36] (LE: 1A)

- Evaluating vertebral slipping and possible neural element compression [6] (LE: 2B) [38] (LE: 1C)

CT and MRI give the best visualization of bone morphology and are therefore, most often used to check the alignment of the facet joints and their degenerative changes. [36] (LE: 1A) [6] (LE: 2B) [38] (LE: 1C) Images resulting from CT and MRI are the most sensitive and specific when a pars fracture is present [9] (LE: 1B)

Myelography can be used together with CT, but nowadays MRI is used instead. [6] (LE: 2B)

Physical examination

The following signs are observable during the physical examination:

- A significant lumbosacral kyphosis [9] (LE: 1B)

- A hyperlordotic posture [9] (LE: 1B)

- Lumbosacral tenderness [9] (LE: 1B)

- A palpable “step-off deformity” [9] (LE: 1B) (37) (LE: 4)

- Pain on lumbar hyperextention (common) [9] (LE: 1B)

- Dull back pain exacerbated by rotation and hyperextension [37] (LE: 4)

- Hamstrings contracture (common) and/or spasms [37] (LE: 4) [39] (LE: 1B)

➔ Gait disturbance: [39] (LE: 1B)

o Crouching [39] (LE: 1B)

o Short stride length [39] (LE: 1B)

o Incomplete swing phase [39] (LE: 1B)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

General [6] (LE: 2B), [40] (LE: 2B)

- Initially resting and avoiding movements like lifting, bending and sports.

- Analgesics and NSAIDs reduce musculoskeletal pain and have an anti-inflammatory effect on nerve root and joint irritation.

- Epidural steroid injections can be used to relieve low back pain, lower extremity pain related to radiculopathy and neurogenic claudication.

- A brace may be useful to decrease segmental spinal instability and pain. [5] (LE: 3B)

Surgery

When the condition is very severe, a surgical intervention may be necessary to attach the vertebras together. The goal of surgery is to stabilize the segment with listhesis, decompress the neural elements, reconstruction of the disc space height and restoration of normal sagittal alignment. [1] (LE: 2A) [41] The grade of listhesis can be reduced to some extent, but complete reduction is rarely achieved. (41) There is a wide variety of complications, such as neurological complications, vascular injury, instrument failure, and infections. (1) (LE: 2A) (6) (LE: 3B) (39) (LE: 2B)

There are several different options for surgical treatment; one of them is fusion (e.g. posterolateral fusion). The aim of fusion is to reduce pain by reducing the motion of the segment. Other treatment options include decompression (Gill laminectomy), supplemental instrumentation and supplemental anterior column support. Controversies exist about the effectiveness of these treatment options that can be used separately or in any combination. (6) (LE: 3B) (39) (LE: 1A)

A surgical intervention has better results than nonoperative treatment in case of neurological symptoms and for treating pain and functional limitation. [42] (LE: 1B) [43] (LE: 1A) [40] (LE: 2B)

When evaluating a patient, many factors, such as age, degree of slip and risk of slip progression, must be considered. Also a thorough evaluation of social and physiological factors should be undertaken. Therefor each patient's treatment program should be individualized to achieve optimal outcome.

[1] (LE: 2A) [41]) (LE: 2C)

Indications [6] (LE: 2B) [1] (LE: 2A) [43] (LE: 1A)

- Neurologic signs / neurogenic claudication / radiculopathy (unresponsive to conservative measures)

- Myelopathy

- High-grade slip (>50%)

- Type 1 (congenital) and 2 (isthmic) slips with evidence of instability, progression of listhesis, or lack of response to conservative measures

- Type 3 (degenerative) listhesis with gross instability and incapacitating pain

- Bladder or bowel symptoms (especially in type 3)

- Traumatic spondylolisthesis

- Iatrogenic spondylolisthesis

- Postural deformity and gait abnormality

Contra-indications [1] (LE: 2A)

- Poor medical health

- High operative risk (higher risk than potential benefits)

- High risk of hemorrhage: Anticoagulation with warfarin, or antiplatelet therapy

- Smoking

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

If there are no indications for surgery (as described above in medical management) physical therapy is always recommended to start with. Optionally in combination with medication or bracing.

Nonoperative treatment should be the initial course of action in most cases of degenerative spondylolisthesis and symptomatic isthmic spondylolisthesis, with or without neurologic symptoms. [42] (LE: 3A) Children or young adults with a high-grade dysplastic or isthmic spondylolisthesis or adults with any type of spondylolisthesis, who does not respond to nonoperative care, should consider surgery. In all the other cases, spondylolisthesis should be treated first with conservative therapy, which include physical therapy, rest, medication and braces. [44] (LE: 3A)

Traumatic spondylolisthesis can be treated successfully using conservative methods, but most authors suggested it would result in posttraumatic translational instability or chronic low back pain. [45] (LE: 3A)

There is strong evidence that exercise therapy, which consists of strengthening exercises, isometric and isotonic exercises, stretching exercises, lifting techniques and endurance training, is effective for chronic low back pain (level 1) [46] (LE: 1A).

Physical therapy treatment may include strengthening of the deep abdominal musculature. [47] (LE: 1B) [46] (LE: 1A). In addition, isometric and isotonic exercises may be beneficial for strengthening of the main muscle groups of the trunk, which stabilize the spine. These techniques may also play a role in pain reduction [47] (LE: 1B) [46] (LE: 1A) [48] (LE: 1B).

In order to improve the patient’s mobility, physical therapy includes stretching of the hamstrings, hip flexors and lumbar paraspinal muscles [47] (LE: 1B) [46] (LE: 1A).

The objective of stretching and strengthening is to decrease the extension forces on the lumbar spine, due to agonist muscle tightness, antagonist weakness, or both, which may result in decreased lumbar lordosis [47] (LE: 1B) [46] (LE: 1A).

Special attention has to be given to posture and proper lifting techniques [49] (LE: 3A), wherein the physiotherapist has an important educational role [47] (LE: 1B) [46] (LE: 1A).

An excellent exercise is stationary bicycling, because it promotes spine flexion.

Sports that can be practiced are walking, swimming and cross-training. Although these activities will not improve the shift, these sports are a good alternative for cardiovascular exercises [6] (LE:2B). Impact sports like running should not be done in order to avoid wear. The adolescent athlete or manual laborer should avoid hyperextension and/or contact sports [49] (LE: 3A).

Exercises should be done on a daily basis [6] (LE: 2B).

Figure 3: Strengthening of the deep abdominal muscles.

Alternating legs, with leg extension while exhaling, maintaining contraction of transverse abdominis, paravertebral and pelvic floor muscles [50] (LE: 1B).

Figure 4: Horizontal side support exercise for corestability [51] (LE: 1B).

Figure 5: Stretching of the erector spine muscles.

Flexing of the hip, toward the chest [50] (LE: 1B).

Prateepavanich et al. showed a statistically significant improvement in walking distance (393.2±254.0m and 314.6±188.8m) and reduction of pain score in daily activities (4.7±1.4 and 5.9±1.0) with and without lumbosacral corset dressing respectively [52] (LE: 2B).So, a lumbosacral corset can be used to improve walking distance and to reduce pain in daily activities [52] (LE: 2B) , but it does not reduce the shift of the vertebra [6] (LE:2B). It is a good aid during the painful periods but should be discontinued when the patients' complaints are reduced.

Key Research[edit | edit source]

add text here relating to key evidence with regards to any of the above headings

Clinical Bottom Line

[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

add links to case studies here (case studies should be added on new pages using the case study template)

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1266860-overview: Amir Vokshoor et al., Spondylolisthesis, Spondylolysis, and Spondylosis. Medscape, updated Sep 10, 2014, Consulted on Oct 20, 2014 (Level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ Tebet, M.A. (2014). Currents concepts on the sagittal balance and classification of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia, 49 (1), 3-12. (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Youtube. (2011). Spondylolisthesis - DePuy Videos. Consulted on Nov. 22, 2014, on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DlJM2kLGwUI (last accessed 13/10/2014)

- ↑ Garet M. et al., Nonoperative treatment in lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: a systematic review, Sports Health, 2013 May; 5(3):225-32 (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Funao H. et al., Comparative study of spinopelvic sagittal alignment between patients with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis, Eur Spine J, 2012; 21:2181-2187 (Level of evidence 3B)

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 Kalichman L, Hunter D.J., Diagnosis and conservative management of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis, Eur Spine J, 2008; 17:327-335 (Level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ Been E. et al, Geometry of the vertebral bodies and the intervertebral discs in lumbar segments adjacent to spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: pilot study, Eur Spine J, 2011; 20:1159-1165 (Level of evidence 3B)

- ↑ Labelle H. et al., Spino-pelvic alignment after surgical correction for developmental spondylolisthesis, Eur. Spine J, 2008; 17:1170-1176 (Level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 Foreman P. et al, L5 spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis: a comprehensive review with an anatomic focus, Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):209-16 (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Frymoyer, J.W. (1994). Degenerative spondylolisthesis: diagnosis and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Orthaedic Surgeons, 2, 9–15. (Level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ McTimoney, C.A., Micheli, L.J. (2003). Current evaluation and management of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 2, (1), 41–46. (Level of evdidence: 2A)

- ↑ Taillard, W.F. (1976). Etiology of spondylolisthesis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 117, 30–39. (Level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Stewart, T. (1953). The age incidence of neural arch defects in Alaskan natives, considered from the standpoint of etiology. The American Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 35, 937–950. (Level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Lonstein, J.E. (1999). Spondylolisthesis in children Cause, natural history, and management. Spine, 24, (24), 2640–2648. (Level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Sonne-Holm, S., Jacobsen, S., Rovsing, H.C., Monrad, H., Gebuhr, P. (2007). Lumbar spondylolysis: a life long dynamic condition? A cross sectional survey of 4,151 adults. European Spine Journal, 16, 821-828. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Amato, M., Totty, W.G., Gilula, L.A. (1984). Spondylolysis of the lumbar spine: demonstration of defects and laminal fragmentation. Radiology, 153, 627-629. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Weil, Y., Weil, D., Donchin, M., Mann, G., Hasharoni, A., (2004). Correlation between pre-employment screening X-ray finding of spondylolysis and sickness absenteeism due to low back pain among policemen of the Israeli police force. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 29, 2168-72. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Kalichman, L., Kim, D.H., Li, L., Guermazi, A., Berkin, V., Hunter, D.J. (2009). Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: prevalence and association with low back pain in the adult community-based population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 34, 199-205. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Belfi, L.M., Ortiz, A.O., Katz, D.S. (2006). Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 31, E907-10. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Steven, S.A., Jeffrey, S.F., (20mc10). Contemporary management of isthmic spondylolisthesis: pediatric and adult. The Spine Journal, 10, 530-543. (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Saraste, H. (1987). Long-term clinical, radiological follow-up of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. The Journal of Pediatric Orthophedy, 7, 631–8. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Fitzgerald, J., Newman, P.H. (1976). Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 58, 184–192. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Sheng-Dan, J., Lei-Sheng, J., Li-Yang, D. (2011). Degenerative cervical spondylolisthesis: a systematic review. International Orthopaedics (SICOT), 35, 869-875. (Level of evidence: 3A)

- ↑ Vibert, B.T., Sliva, C.D., Herkowitz, H.N. (2006). Treatment of instability and spondylolisthesis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 443, 222–227. (Level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ Sengupta, D.K., Herkowitz, H.N. (2005). Degenerative spondylolisthesis: review of current trends and controversies. Spine, 30(Suppl), S71–S81. (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ N.J. Rosenberg. Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Predisposing factors. The journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (1975) 57:467-474. (1C)

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Mays, S. (2006). Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, and lumbo-sacral morphology in a medieval English skeletal population. American Journal of Physical Anthropolgy, 131, 352–62. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Frymoyer, J.W. (1992). Degenerative spondylolisthesis. In: Andersson GBJ, McNeill TW (eds) Lumbar spinal stenosis. Mosby Year Book, St Louis. (Level of Evidence: 5)

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Sairyo, K., Goel, V.K., Vadapalli, S., Vishnubhotla, S.L., Biyani, A., Ebraheim, N. et al. (2006). Biomechanical comparison of lumbar spine with or without spina bifida occulta: a finite element analysis. Spinal Cord, 44, 440–4. (Level of evidence: 2C)

- ↑ Burkus, J.K. (1990). Unilateral spondylolysis associated with spina bifida occulta and nerve root compression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 15, 555–9. (Level of evidence: 3B)

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Toshinori, S, Koichi, S., Naoto, S., Hirofumi, K., Natsuo, Y. (2010). Incidence and etiology of lumbar spondylolysis: review of the literature. Journal of Orthopaedic Science, 15, 281-288. (Level of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Sakai, T., Yamada, H., Nakamura, T., Nanamori, K., Kawasaki, Y., Hanaoka, N. et al. (2006). Lumbar spinal disorders in patients with athetoid cerebral palsy: a clinical and biomechanical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 31, E66–70. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Ogilvie, J.W., Sherman, J. (1987). Spondylolysis in Scheuermann’s disease. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 12, 251–3. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Greene, T.L., Hensinger, R.N., Hunter, L.Y. (1985). Back pain and vertebral changes simulating Scheuermann’s disease. Journal of Pediatrics Orthopedics, 5, 1–7. (Level of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Fisk JR, Moe JH, Winter RB. Scoliosis, spondylolysis, and spondylolisthesis: their relationship as reviewed in 539 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1978;3:234–45. (Level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Tsirikos AI, Garrido EG. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Jun;92(6):751-9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B6.23014 (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Thein-Nissenbaum J, Boissonnault WG. Differential diagnosis of spondylolysis in a patient with chronic low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005 May;35(5):319-26. (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ 38.00 38.01 38.02 38.03 38.04 38.05 38.06 38.07 38.08 38.09 38.10 38.11 38.12 Metzger R, Chaney S. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: what the primary care provider should know. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014 Jan;26(1):5-12. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12083. (Level of evidence 1C)

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 Phalen GS, Dickson JA (1961) Spondylolisthesis and tight hamstrings. J Bone Joint Surg 43:505–512 (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 James N. Weinstein, Surgical versus Nonsurgical Treatment for Lumbar Degenerative Spondylolisthesis,New England Journal of Medicine. May 2007; 356:2257-2270. (Level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Chang Hyun Oh et al., Slip Reduction Rate between Minimal Invasive and Conventional Unilateral Transforaminal Interbody Fusion in Patients with Low-Grade Isthmic Spondylolisthesis, Korean J Spine, 2013 (Level of evidence 2C)

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 L. Kalichman et al. Diagnosis and conservative management of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J (2008) 17;327 – 335. (2B)

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 K Sairyo, Decompression Surgery For Lumbar Spondylolysis Without Fusion: A Review Article, The Internet Journal of Spine Surgery, 2005. (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Serena S. Hu et al., Spondylolisthesis and Spondylolysis, J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2008 Mar 01;90(3):656-671 (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Tang S. Treating Traumatic Lumbosacral Spondylolisthesis Using Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion with three years follow up. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 2014;30(5):1137-1140. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 van Tulder M.W. et al, Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions, Spine, 1997; 22(18): 2128-2156 (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 Overdevest G.M. et al, Design of the Verbiest trial: cost-effectiveness of surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment in patients with lumbar stenosis, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2011; 12:57 (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ M. Sinaki et al. Lumbar spondylolisthesis: retrospective comparison and three year follow-up of two conservative treatment programs. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989 70:594-598. (1B)

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Agabegi S.S., Fischgrund J.S., Contemporary management of isthmic spondylolisthesis: pediatric and adult, The Spine Journal, 2010; 10:530-543 (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Garcia A.N. et al., Effectiveness of back school versus McKenzie exercises in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain : a randomized controlled trial, Phys Ther, 2013; 93(6):729-47. (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Childs J.D. et al, Effects of traditional sit-up training versus core stabilization exercises on short-term musculoskeletal injuries in US Army soldiers: a cluster randomized trial, Phys Ther, 2010; 90 (10): 1404-12. (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Prateepavanich P. et al., The effectiveness of lumbosacral corset in symptomatic degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis, J Med Assoc Thai., 2001; 84(4):572-6. (Level of evidence 2B)