Reducing pressures on the NHS: the emerging role of the physiotherapist in healthcare reform

Original Editor - Sophie Brewster, Ruaraidh McNaughton, Stephen Rhys Evans, Omar Rasheed as part of the QMU Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Sophie Brewster, Ruaraidh McNaughton, Hetvi Kara, Stephen Rhys Evans, Omar Rasheed, Amy Young, Kim Jackson, Chee Wee Tan, Evan Thomas, 127.0.0.1, Michelle Lee, Admin, Sonja Murphy and Angeliki Chorti

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The goal of this resource is to provide a learning tool for students, recent graduates and junior physiotherapists at a time where integration of health and social care is a priority in service provision. This aims to give them the knowledge and capacity to expand future physiotherapy from what was once a traditional ‘mono-role’ into something advanced, exciting and current. Throughout practice based placements and these initial years, these new practitioners can demonstrate key attributes in foreseeing what services need to be developed to accommodate the changing population. Usually allied health professionals begin their career as graduates then following junior clinical years, will branch into specialisms as their career progresses however emerging roles and physiotherapy pathways are allowing them to structure their career accordingly resulting in practice being undertaken in a variety of untraditional settings.

‘Success requires not only the right vision but also the right workforce’ (DoH, 2008)

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

On completion of this page:

•The learner will be able to identify the knowledge, skills, behaviours and values which are required by physiotherapists working within emerging roles in the NHS.

•The learner will be able to distinguish between different roles in physiotherapy practice and identify the knowledge, skills and qualifications required to work in each area.

•The learner will be able to identify further learning opportunities available to new graduates to assist in progressing to working in an emerging role.

•The learner will be able to critically reflect upon the challenges facing each emerging role and looking to the future, where each role will fit within the NHS.

Guide to Resource[edit | edit source]

This resource is an informative CPD package for new graduates looking into five emerging roles within the NHS. We will explore these roles independently and analyse how these fit into the 20/20 vision and the The National Delivery Plan for the Allied Health Professions in Scotland 2012-2015. We will also consider the pressures on the NHS at present and how each of the emerging roles we have decided upon will impact NHS service provision. We have also included email responses from selected physiotherapists who are working in these roles, in order to gain an insight into their views and experiences.

Content (hyperlinks)

We have selected the following emerging roles within physiotherapy. We are aware that there are many other roles that we will not be covering in the wiki, such as… (ADD TO) We have selected these roles as they have been recently discussed the physiotherapy magazine, Frontline and also at the annual physiotherapy UK conference and trade exhibition 2015 in Liverpool. The roles we have selected all fit into the main theme of the resource, which is relieving time pressures on the NHS.

Emerging roles:

- Prescribing rights

- Physiotherapists in emergency care settings

-Primary care/ GP surgeries - Injection therapy/ acupuncture

- Humanitarian Crisis

We intend to facilitate the learner's deeper understanding of these topics with opportunities for reflection and learning questions throughout. These will be outlined with the symbol: <img src="/images/e/ea/Question_Mark.jpg" _fck_mw_filename="Question Mark.jpg" alt="" />

?? Stepping stones table/ diagram ??[edit | edit source]

Workforce Development[edit | edit source]

Since 1948, the NHS workforce has erupted from approximately 144, 000 staff to a current 1.4 million in England alone with over 300 organisations (NHS, 2013). By 2033 over one quarter of the population will be aged over sixty-five.

Demographically the health service will require future changes such as more first point of contact practitioners, increases in rehabilitation, prescribing abilities, and a higher need for surgical procedures and as a result, AHPs have recently been called upon to provide such services. Too often the range of knowledge, skills and competencies of AHPs is not fully and widely understood (DoH, 2008). Education opportunities and training programmes therefore must be integrally linked into current and emerging models or care in addition to scientific and technological advances. Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) have the talent and capacity to look beyond individual clinical practice and instead can are looking to maximise their contributions by getting involved in partnerships, leadership roles and scientific research (DoH, 2008; 2011).

<p><p>Training and Career Pathways

</p>

</p>

In most health organisations AHP career pathways are well established with junior practitioners progressing into clinical specialists, extended scope or advanced practitioners with a consultant role (ADD DESCRIPTORS)often being the pinnacle career goal. However, 2008 saw the launch of a UK-wide ‘Modernising Allied Health Professions Careers’ project, more recently known as Skills for HealthThis web-based tool was constructed to target AHPs planning more flexible and alternative career pathways to ensure breath and depth of expertise and maximise future employment opportunities. This resource provides professionals with a framework of competencies and includes a web-based resource documenting AHP and support worker roles. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy (CSP) furthered this by providing a physiotherapy specific online resource for members to keep their knowledge and skills updated. This includes a set of learning and development principles, the code of professional values and behaviour and a framework of physiotherapy knowledge and skills hoped to be of use to current practicioners (CSP, 2010). It has been suggested that by offering greater clarity of accountability, responsibility and primary roles at all levels, this will lead to enhanced future workforce planning and training commissioning, ensuring that the in the future, patients will have access to a paramount level of care for their needs.In support of the 2020 vision to achieve a first class integrated workforce in the UK by 2020, this is hoped to aid planning and service redesign and pays particular attention to leadership and the capacity and capability of AHPs. In addition to training, from a commissioner’s perspective these tools help to develop services by maximising the potential of AHPs to play a larger role in transforming care, having the competency to work across organisational boundaries (DoH, 2008). Academia, research and management job opportunities have shifted the focus from effective clinical practice to ensuring this practice is evidence-based and up-to-date and is able to respond efficiently and effectively to accommodate changing service requirements. According to Framework 15 attracting and recruiting the right people into training programmes will benefit workforce planning for the future. Each year Health Education England (HEE) invests £4.8 billion of it’s £5 billion budget on education and training of this prospective workforce (HEE, 2014) to drive healthcare changes. However this said, 60% of this is spent on doctors making up 12% of the workforce while AHPs account for 40% of this population.

</p>

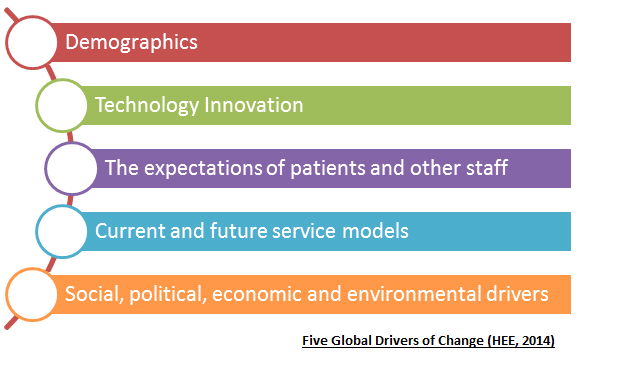

The Department of Health (2008) anticipate that in 10 years time, 60% of the current healthcare workforce will still be providing NHS services. Thus supporting them through career frameworks will help to fulfil their individual potentials. In the Framework 15 document (HEE, 2014) there are five global drivers of change considered. These are demographics; technology innovation; social, political, economic and environmental drivers; current and future service models and finally the expectations of patients and other staff. Workforce planners will utilise these factors when balancing an expected demand with an efficient demand(DoH, 2008).

</p>

</p>

Primary Care[edit | edit source]

Description[edit | edit source]

Primary care is defined as the first point of contact for someone seeking medical care, typically a general practitioner or a family doctor. Primary care acts to coordinate any other specialists that the patient may need (World Health Organisation/Europe 2004).

Self-referral to physiotherapy is not covered in this wiki, as it is not considered a new or emerging role within the profession.

General Practitioners in the UK are suffering from an unstainable workload, which is limiting their appointment times with patients. Despite this, the government continues to push for GP surgeries to be open 7 days a week. If these plans go ahead, the strain placed on these AHPs will continue to grow. Added to the fact that the UK has an aging population, the strain on GPs and the rest NHS will not reach breaking point if drastic changes in primary health care are not made. The following is a quote from Sara Khan, a GP from Hertfordshire (Khan 2013): “patient demand has steadily risen, in many cases from an increasingly ageing population. It is to be celebrated that modern medicine is helping us live longer, but a side effect is that we develop conditions that require expensive care. My appointments with older patients are frequently longer due to multiple, complicated health needs that require careful need and attention. This inevitably eats into the time I have for appointments with other patients.”

This article, <a href="http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/jul/24/stop-blaming-gps-out-of-hours-nhs">avaialble here</a> is one of many highlighting the current issues surrounding primary care in the UK.

This unstainable workload has caused great unrest among GPs, leading to the looming GP crisis. A survey of 1,004 GPs in the UK, as part of the BBC’s Inside Out programme (BBC 2015) found that 56% said they plan to retire before they turn 60. The workload, out of hours working and volume of consultations were some of the reasons for this. A summary of the findings can be found <a href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/latestnews/2015/inside-out-family-doctors">here</a>.

Due to a lack of government funding and the likely shortage of GP’s, the role of physiotherapists in primary care is currently being explored. The importance of the profession in the future of primary care is highlighted in a report by the Primary Care Workforce Commission (2015). <a href="http://hee.nhs.uk/wp-content/blogs.dir/321/files/2015/02/The-future-of-primary-care-v7-webFINAL.pdf">The report</a> endorses self referral to services and highlights the potential benefits of physiotherapists working alongside GPs, as a first point of contact for patients. Physiotherapists pride themselves for being autonomous in assessing, diagnosing, treating and discharging patients. Some advanced practitioners and extended scope practitioner physiotherapists are trained to prescribe drugs and provide injection therapy to patients.

“GPs within the West Wakefield Health and Wellbeing Project have developed a hypothesis that 50% of a GP’s workload could be undertaken by other staff. I want physiotherapy to form a significant part of this 50%” Dr Chris Jones, Programme Director, West Wakefield Health and Wellbeing Project.

(Taken from CSP leaflet: physiotherapy works for primary care (CSP LEAFLET). A link to the leaflet can be found <a href="http://www.csp.org.uk/professional-union/practice/your-business/evidence-base/physiotherapy-works/primary-care">here</a>.

<img src="/images/7/70/Physio_works_for_primary_care.png" _fck_mw_filename="Physio works for primary care.png" alt="" />

Rachel Newton, the CSP’s head of policy, has asked for CSP physiotherapists with experience of working in primary care to come forward and share their experiences. She told Frontline magazine “Evidence from members is essential to making the case to decision makers for the potential for physiotherapy within primary care” (CSP 2015ii). The <a href="http://www.csp.org.uk/icsp/primarycare">Primary Care iCSP group</a> was set up for CSP members to share experiences and benefits of physiotherapy in primary care.

Question: Isn’t self referral to physiotherapy the same as seeing a physiotherapist in primary care?

Answer: No. As with any self referral to a health service, you will still be placed on a waiting list. Ideally waiting times for Physiotherapist working in primary care will be the same as for GPs.

Cost Effectiveness[edit | edit source]

The main proposed benefit of physiotherapists working in primary care is reducing healthcare costs. It is estimated that MSK conditions make up 30% of a GPs appointments, yet 85% of those do not need to see a GP (Ludvigsson and Enthoven 2012). If patients were offered different professionals as their first point of contact, a huge number of GP appointments would be made available. The following costs saving benefits have been suggested by a CSP leaflet: physiotherapy works for primary care (CSP LEAFLET).

- Reduce referrals to secondary care orthopaedics

- Reduce unrequired investigations (x-ray, MRI)

- Reduce onward referrals to physiotherapy in community and secondary care

- Increase the number of patients able to self-manage effectively increase the number of referrals to leisure centres and other forms of physical activity prevention

However, there is no reference provided for these statements, therefore their relevance is questionable.

An <a href="http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/vanguard-primary-care-treatment-musculoskeletal-conditions">article</a> in Frontline magazine (CSP 2015i) describes the need for physiotherapy as a profession to adapt and expand in response to the NHS England’s Five year forward view (NHS ENGLAND 2014). This calls for a step change in the integration of services to improve primary care. The frontline article is focuses on the 5-year journey of Amanda Hensman-Crook, formally a band 8a physiotherapist. After a successful 3 month pilot working alongside GPs, she was offered a permanent post at the GP practice, under the new title of MSK practitioner. Her pilot was based on estimates that approximately one in three GP consultations are MSK related. An audit of the service since June 2015 suggests a 20% fall in referrals to secondary MSK treatment. GPs and patients were found to be very happy with the service. A downside of this innovative service is that physiotherapists in this role will have shorter appointment times with patients. According to the article, the Hampshire service offers a 20 minute consultation, which is half the typical appointment time for a secondary care MSK service. This shows that physiotherapists can be effective in working alongside GPs as a first point of contact. If physiotherapists have the required knowledge and skills, they can relieve some of the pressures on GPs in primary care. The reduction in referrals to secondary MSK treatment highlights the money saving benefits of this system.

<img class="FCK__MWTemplate" src="http://www.physio-pedia.com/extensions/FCKeditor/fckeditor/editor/images/spacer.gif" _fckfakelement="true" _fckrealelement="4" _fck_mw_template="true">

Youtube Video – NHS Wales – advanced MSK physiotherapists

Training/ Qualifications[edit | edit source]

From the literature, it appears to mainly advanced practitioner physiotherapists who are working alongside GPs in primary care. Amanda Hensman-Crook, who began working in a GP practice LINK, was a band 8a physiotherapist before she started working under the title of advanced practitioner. The following is a link to a short descriptor of advanced practitioner physiotherapists. LINK . Further training/qualifications to become an advanced practitioner physiotherapist include:

- One year university courses, such as the MSc advanced practitioner physiotherapist course at the University of East Anglia. These courses offer further learning for qualified physiotherapists in advanced areas, such as independent and supplementary prescribing.

- A high level of experience is required by employers. Band 5 physiotherapists will first have to specialise in one area of physiotherapy and then gain considerable experience in this area.

Band 7 physiotherapists are expected to take up a leadership role within the team. This includes helping less qualified physiotherapists further their learning through CPD exercises. They are also expected to be comfortable managing complex cases and be experts in reviewing emerging evidence within their area of specialised knowledge.

A barrier to progressing to advanced practitioner level is course fees for advanced physiotherapy masters courses. Fees range from £7000 for UK/EU students to £15000 for international students.

As working in primary care is an emerging role in physiotherapy the NHS is still piloting the idea around the UK. As a result, there is no recognised progression pathway beyond reaching an advanced practitioner level of expertise.

Evidence to support[edit | edit source]

A study by Ludvigsson and Enthoven (2012) evaluated physiotherapists as primary assessors of patients with MSK conditions. 51 patients with a MSK disorder were primarily assessed by a physiotherapist and 42 by a GP. Participants completed a patient satisfaction questionnaire. It was concluded that physiotherapists can be used as primary assessors of MSK conditions in primary care, as few patients needed additional GP assessment. The physiotherapists were found to be capable of identifying confirmed serious pathologies and patient satisfaction was higher with physiotherapists than GPs. The participants who were seen by a physiotherapist felt confident in the information they received and the support to self-manage their conditions. The main limitation of the study, acknowledged by the authors was the participants were not randomly allocated to be seen by a physiotherapist or GP, thereby researcher bias is not excluded.

A study by Pinnington, Miller and Stanley (2004) evaluated prompt access to physiotherapy in the management of low back pain in primary care. The authors identify the issue of delays in getting access to specialised treatment in patients with low back pain. In the study, physiotherapist-led back pain clinics were established. Results were compared other published interventions from the literature. Data on pain, disability and well-being were collected at recruitment and 12 weeks later. The patients maintained diaries and GPs were interviewed before and after the study to obtain qualitative data. Comparative costings were derived from national and local sources. Results showed that more than 70% of the 614 patients seen only required a single visit and the majority of the patients were seen within 72 hours. Prompt access to physiotherapy reduced time taken off work and cost less per episode of back pain, compared with normal management. Qualitative data showed that patients valued early access to physiotherapy, particularly for reassurance. GPs also praised the service, largely due to the positive patient responses. This study shows the cost effectiveness among benefits of using physiotherapists as a first point of contact for patients with low back pain. This is more significant given low back pain is the most commonly presented MSK condition (Pinnington, Miller and Stanley 2004). A limitation is the study is from 2004, therefore the practices used by the physiotherapists are likely to be outdated. The study also does not specify the level or qualifications of the physiotherapists.

Holdsworth, Webster and McFadyen (2008) investigated physiotherapists and GPs views on self-referral and physiotherapy scope of practice. Data was gathered using a survey questionnaire, with both qualitative and quantitative questioning. They found the idea of physiotherapists working as first point of contact is strongly supported by the majority of physiotherapists and GPs. Potential benefits for patients were identified if physiotherapists adopted extended roles within a MSK setting, such as injection therapy and prescribing medications.

The following are examples of positive comments from physiotherapists and GPs extracted from Holdsworth, Webster and McFadyen (2008)

GP comments:

It makes logical sense, after all, physios are the experts when it comes to managing many musculoskeletal conditions’

Physiotherapists’ comments:

‘I was rather nervous of seeing self-referring patients at the start, wasn’t sure what to expect but now feel much more confident, it's just a question of being thorough and nothing more really’

‘I’m happy as I know that if I have any concerns, I can get the patients seen by their GP really quickly’

‘Our GPs have been great and want us to take on more aspects of the patients’ management as they see the time it could save them and they must trust us to want us to do this’

The Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board (2015) in North Wales published results from a pilot study, in which advanced MSK physiotherapy practitioners are working in GP practices. LINK. It shows an additional 671 appointments were made available during the six-month pilot phase. Around one third of the appointments were MSK related which helped free-up GPs to concentrate on other patients and more complex cases. This data is from a National Health Board website, therefore can be deemed reliable.

In summary, an expansion of physiotherapy within primary care provides an immediate solution to GP shortages and delivers the transformation of primary care needed for a sustainable health system tailored to modern population needs (CSP 2015). More clarity is needed on how to reach these roles working alongside GPs in primary care and the additional qualifications required.

Self assessment questions:

1. From the above studies, what are the main proposed benefits of physiotherpaists working in primary care?

2. How did the patients feel about being seen by physiotherapists, rather than GPs?

Challenges[edit | edit source]

As the concept of physiotherapists working alongside GPs is at the piloting stage, there is currently no established pathway beyond reaching an advanced practitioner or band 7 level of expertise. Because of this there are currently no postions in primary care being advertised for physiotherapists in the UK. From the research there appears to be no disadvantages of using physiotherapists as first point of contact as for MSK conditions. It is woth noting that the studies in the literature only use physiotherapists for MSK conditions. The ability of physiotherapists working in GP practices to assess, diagnose and treat patinets with other conditions, such as neorological remains to be seen. One challenge is training physiotherapists to the required level of expertise. However, the experience as working as a MSK specialist for a number of years appears to be sufficient.

Physiotherapists in Emergency Care Settings[edit | edit source]

Description[edit | edit source]

In recent years, physiotherapists have been placed in accident and emergency (A&E) departments to improve patient care, free up hospital beds by preventing unnecessary admissions and target optimal functioning of attendees. Emergency department physiotherapy is incorporated in the umbrella of an extended scope of practice. Clinicians in this area display a considerable depth of academic knowledge, clinical skills and experience and may be involved in providing interventions traditionally beyond the physiotherapy scope of practice (Anaf & Sheppard, 2007). In addition to frontline emergency physiotherapy practitioners (EPPs), increasingly physiotherapists are being made part of the integrated multidisciplinary team working in A&E and on medical assessment units (CSP, 2011). In Scotland such teams are seen at the Borders General Hospital where the Rapid Assessment and Discharge team are heavily involved in early patient contact, and the Integrated Assessment Team at the Victoria Hospital in Fife who carry out a falls assessment on every patient over the age of 64 attending A&E and assist with safe discharge (NHS Fife, 2014). It is recommended that 80% of patients attending A&E not staying in to be admitted should have length of stay less than 240 minutes (Taylor et al. 2011). These practitioners support medical professionals in assessing patients presenting with musculoskeletal conditions, helping to reduce breaches of this four hour waiting target and excessive delays (CSP, 2011)BBC News Article: A&E Waiting in England Worst for a decade.This allows patients to be assessed and either admitted or discharged home in a timely and safe manner with the appropriate resources in an attempt to prevent future re-admissions. The physiotherapist is also able to liaise with the MDT in deciding if the patient requires further input such as increased care package or community physiotherapy. In August 2013, in response to NHS England’s urgent and Emergency Care Review, the CSP confronted the increased need for physiotherapy services in acute medical departments, including A&E (McMillan, 2013).To meet the growing demands of emergency healthcare, EPPs operate as frontline staff whose role includes the assessment of musculoskeletal conditions, sending for further investigations such as bloods and scans, the management of soft tissue injuries and wounds in addition to educating and advising. This allows for doctors working in the department to focus their attention to more complex acute cases and improves the flow of patients through the system. Frontline physiotherapists are particularly relevant in treating the elderly where admission to hospital is much more likely to result in a consequential spiral of hospital acquired infections, delirium and often reduced functional capacity, resulting in extended stays. An increasing elderly population and patients with two or more long term conditions has recently meant two out of three A&E visits are for those falling into these brackets and with increased access to GP out of hours services since 2004 there has been an additional 4 million A&E attendants (Reesᵃ, 2015). Increases in bed occupancy yet a 6% decrease in bed numbers since 2010 has seen patients being shifted between wards, putting further extension on their length of stay (Reesᵇ, 2015) Historically allied health professionals in A&E were occupational therapists due to their main role in the organisation of discharges. However, with the integration of health and social care advancing multidisciplinary team working, currently in situations such as these, there is an overlap in physiotherapist and occupational therapist roles in order to provide the best possible approach to patient-centred care.

One of our student editors has placement experience with the RAD team at the Borders general Hospital near Melrose. She reports:

“The Rad team which was still being piloted at the time of my placement was made up of one band 6 physiotherapist, one occupational therapist and a further senior physiotherapist with a dual physiotherapy and social care role. Although I was only there for a short period, it was clear the positive effects this set up was having on acute care and I really enjoyed being part of something current and emerging. We aimed to see patients within 12 hours of attending A&E if required, whether that be on the Medical Assessment Unit following admission or if they were discharged home we would contact them via the phone and even go and see them in the community when necessary. The set up of the team enabled interdisciplinary assessments of mobility and functional ability e.g. self-care to occur, providing patients with the appropriate resources and equipment to ensure a safe discharge and reduce the change of future re-admission. In A&E the majority of the patient’s we saw had newly acquired walking aids so time was spent teaching their use and working with the patient to ensure they were able to function optimally and safely in their home environment. We also saw patients who had long term conditions that unrelated MSK problems were now making harder to manage.

My favourite aspect of the placement was the variation. One day could be spent in MAU, preparing patients for discharge without any requirement for the team in A&E while other days could be spent solely in A&E or out on home-visits without a hospital ward in sight. This highlighted to me how the profession is changing as we try to move care out into the community. I was aware however of some challenges facing the team. Due to being a pilot the team was still establishing itself across the hospitals, with better knowledge of its purpose in some areas than others. This also meant that here was also no set protocol as to when RAD input was sourced and different methods of triage were being tried and tested over the course of my placement. This finished with the prospect of the RAD team being based in the A&E department to increase awareness. I did not have any doubt however that with a bit of perseverance this would happen.”

In view of this tight window in which to see suitable patients, NHS London Care Commissioning Standards (NHS Healthcare for London, 2011) state that many hospitals have reviewed their A&E services, extending emergency physiotherapy input to cover weekends and extended hours in order to maximise the cost-effectiveness of the service.

Cost Effectiveness[edit | edit source]

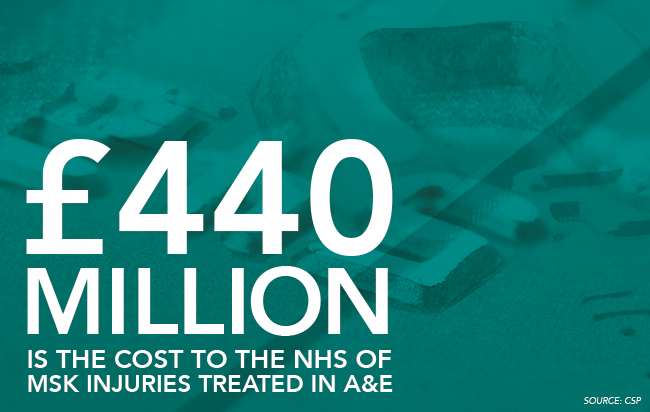

With the average cost of an A&E visit costing the NHS approximately £115 this method of service provision reduces direct costs with similar clinical outcomes (CSP, 2011). The CSP evidence-based briefing Physiotherapy Works: Accident and Emergency found that in 2012-2013 of the 18.3million people that attended A&E, around 21% presented with musculoskeletal (MSK) related injuries, an estimated £440 million worth of healthcare costs.

It was recorded that 446000 more people attended emergency departments throughout the UK in 2014 compared to 2013 (Reesᵃ, 2015). Winter 2014-2015 therefore saw huge negative media coverage of A&E provision with increased demand and rises in missed targets with higher reported major incidents (Jenner, 2015; Reesᵃ, 2015)BBC News Article: NHS set for a bumpy start to 2015. Incapacity in emergency departments was quoted as being “the biggest operational challenge facing the NHS” (Reesᵃ, 2015).In light of this, it is being more accepted that in order to lower the pressures and direct costs of these deficiencies, the skill mix of AHPs should be exploited (Jenner, 2015). If used properly, the abilities of physiotherapists could bring huge benefits in the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of MSK and chronic respiratory exacerbations such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder, in addition to providing vast experience and learning opportunities for the physiotherapists themselves (Jenner, 2015).

Training/ Qualifications[edit | edit source]

Integration of roles requires training at masters level in addition to being signed off as competent. McMillan (2013) reports the role as a challenging varied environment with a high degree of responsibility and that previous MSK experience will assist with the management of what comes literally through the front door. Conditions can include minor head or rib injuries which if dealt with incorrectly can mean dealing with life or death situations (McMillan, 2013). Richard Parris a consultant in emergency medicine is optimistic about the future of physiotherapists in the emergency department: “the physiotherapists are a real asset…we don’t have any hierarchy or boundaries”, however reports that it is not for the faint hearted (McMillan, 2013).

In Australia, emergency physiotherapists must have a minimum of 5 years clinical practice post-graduation including 3 years spent in a relevant specialist area. Additional training or postgraduate study in a relevant clinical area is also desirable (Crane & Delany, 2011). However, there is currently a lack of a clear direct career pathway to get to this position meaning that practitioners are responsible for developing their own range of specialist skills. MSK postgraduate or masters certificates tend to be more directed at outpatient and private physiotherapy roles instead of for use in the emergency department. In Australia, most emergency physiotherapists are undertaking short courses such as plastering, sports, spinal and vestibular to complement their practice.

It has been realised that educational requirements for this sort of role placed within the broader health system network, however, needs to be standardised across settings in order to establish the wider effect of the service. Educational support including onsite training and supervision can be used as part of the programme in addition to certified courses in the absence of specific qualifications however this still means there is a lack of overall structure of training and defines the need for evidence-based regulatory.

Evidence to support[edit | edit source]

The UK is the worldwide leader in innovative physiotherapy practice (Crane&Delany, 2013). Services are continuously changing to meet the growing and changing patient demands while increasing workforce flexibility (Crane & Delany, 2013). As a result there is an evolving need to provide practitioners with an ethical and evidence-based framework to support changing practice such as the development of the emergency physiotherapist role. Within Australia, career paths are widening for physiotherapists as they try to establish similar counterparts (Crane&Delany, 2013) due to an increasing demand on emergency departments. Some would argue the emergency physiotherapist role has been better suited to the political need to improve patient waiting times rather than patient outcomes, however, Taylor et al. (2011) found that patients with musculoskeletal problems presenting at A&E were just as, if not more satisfied to see a physiotherapist as the first point of contact. Crane and Delany (2013) suggested that musculoskeletal physiotherapists expand their physiotherapy practice in the emergency department by requesting and interpreting radiology results, blood tests,x-rays managing minor wounds and fractures, applying plaster, managing analgesia and referring on to the most appropriate option in an efficient manner. Although predominantly involved with the management of MSK conditions Effectiveness of musculoskeletal emergency practitioners. Anaf and Sheppard (2007) comment on the emergency Physiotherpists role in effectively managing minor chest fractures, whiplash, recent burns limiting functional movement and torticolosis.

Similar to the UK, in Australia Crane and Delany (2013) found that EPs enabled doctors to treat more critical and complex patients faster and reduced overall waiting time through the emergency department. Taylor et al. (2011) found that when operating as primary contact practitioners, patient length of stay could be reduced by up to 59.5 minutes compared with secondary contact practitioners. In the same non-randomised controlled trial, waiting time and treatment time of those attending A&E was also reduced following treatment by an emergency physiotherapist compared to secondary contact. This was thought to be a result of bypassing the initial doctor’s assessment. In addition to reducing the workload of other staff, this system improved patient flow and had no significant impact on re-presentation rate (Taylor et al. 2011) When satisfaction rates were investigated in this study, 85% of patients attending a physiotherapist in the emergency department were satisfied with the treatment they received as were 82% of patients who first saw a doctor followed by a physiotherapist. However, those receiving the primary physiotherapy contact felt things were explained more effectively and that they were given more time to ask questions and discuss their condition (Taylor et al. 2011).

The systematic review conducted by Kilner (2011) analysed the literature surrounding physiotherapists working as emergency practitioners, specifically its effect on health outcomes. Despite the previous findings, this research review did not fully support the engagement of physiotherapists in the emergency care setting. The ‘access block 'experienced across emergency departments worldwide requires government, economic and societal input overtime with physiotherapists working in emergency departments only a short-term solution to a long-term problem. However, Jogodka and Lebec, (2008) argue the need for mobility and exercise experts in the emergency departments and that when used appropriately, physiotherapists seen here can facilitate healing and prevent secondary complications. Kilner (2011) analysed that emergency physiotherapy affects outcomes on three main levels: system, provider and client. It was determined that although physiotherapists working in A&E were more likely to give advice to patients and arrange for follow up physiotherapy that doctors or nurses working in the same area, at a system and provider level, there is insufficient existing evidence regarding the effects of physiotherapy in A&E. Richardson et al. (2005) for example conducted a randomised controlled trial which failed to establish the cost-effectiveness of such a service. Kilner (2011) agreed that emergency physiotherapy resulted in increased patient satisfaction, decreased waiting times and improved clinical outcomes in the short term, however were not convinced of the reliability of its long term effects.

A further selection of hospitals offering related services in the UK (please note this list is not exhaustive, it gives examples of the emergency physiotherapy services currently offered across the UK).

● Salford Royal NHS Foundation treats 88500 patients in A&E annually. In 2010 an advanced physiotherapy practitioner role was introduced in the department to treat MSK presentations. This includes the ordering of x-rays and further tests in addition to managing on-going referrals. This service has been proposed to reduce waiting times while providing high quality and efficient service with direct access to a physiotherapist available to all presenting patients. The foundation has reported a cost saving of approximately £32 per patient (a 60% reduction) largely due to a reduced need for more expensive medical staff.

● The Royal Bolton Hospital provides clinical specialist physiotherapists in their A&E department to deal with their relentless influx of patients and attributes much of their success and enviable record of prompt treatment and discharge to this provision. Usman Arif is one of these practitioners and also clinical lead for three additional physiotherapists sharing their time between the emergency department and MSK outpatients. He comments: “Every day here is different. It’s stimulating and the workload is so varied I learn something new every week” (McMillan, 2013). The first pilot scheme was launched in 2003 with working hours 8am-4pm weekdays and 8-6pm at weekends with enhanced pay (McMillan, 2013). In addition doctors in A&E have the scope to request a second opinion of a physiotherapist at a later date when very acute injuries and pain can limit their own initial assessment. Mr Arif went on to report:

we work with “minors” [those with less serious illnesses or injuries] as autonomous practitioners with an extended scope of practice, and also provide some input to paediatrics.

Furthering this, many of the physiotherapists in this role are working towards their right to independently prescribe. Often already holding supplementary prescribing rights, Mr Arif comments that this is not adequate when working in A&E with patients you don’t see on a regular basis.

● At Derriford Hospital in Plymouth (2015), Physiotherapists work in a variety of settings including A&E. The medical rehabilitation team provide a seven day service across emergency care including the Medical Assessment Unit, short-stay ward, Clinical Decision Unit and A&E whilst also proving a six day service to the care of the elderly wards. The team work across disciplines to provide optimal care and work together to plan appropriate discharges for patients with a variety of musculoskeletal, respiratory and neurological conditions.

● The Burton HospitalS NHS Foundation Trust (2015) in Staffordshire hold a physiotherapy clinic in the Emergency Department where people with acute musculoskeletal or sports related injuries such as sprains and acute back pain can be treated imminently preventing recurrence and shortening recovery time. This also allows the physiotherapists to arrange follow-up physiotherapy in the department or outpatient department for longer term treatment as and when required. The physiotherapists in the emergency department work very closely with the A&E consultants, doctors and nurses and are thus able to refer patients on for further assessment by the appropriate professional should it become necessary. Like the RAD team in the Borders, the doctors and nurses are able to make referrals to the emergency physiotherapists should patients attend out of normal clinic hours who will be contacted promptly and further assessment arranged with them.

● The Physiotherapy service offered by the Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS trust across Pinderfields Hospital, Dewsbury and District Hospital and Pontefract includes an emergency on-call physiotherapist 24 hours a day via an out-of-hours on call service. This provides patients with reassurance that they have access to a physiotherapist directly. and outside of normal 8am-5pm clinical hours. Additionally their ‘Physio Direct’ service allows patients to speak to a physiotherapist at certain hours throughout the day regarding musculoskeletal and soft tissue injuries. This service provides patients with the appropriate further information and contacts if necessary or the physiotherapist may arrange for an outpatient appointment to be made. This therefore reduces the amount of minor injuries walking through the doors of the A&E department.

Challenges[edit | edit source]

The biggest challenge to physiotherapists working in emergency care settings is a lack of adequate funding as explained by... (VIDEO CLIP).Crane and Delany (2013)however also found that there was a possibility that patient satisfaction with primary contact physiotherapists could be due to the decreased waiting time they experienced rather than the interaction had and treatment received from the professional. In addition to this they found that there was nothing specific to say that the decreased waiting times were not due simply to an extra member of staff working in the department, not necessarily a physiotherapist. However they felt that by varying the skill mix in the department, better outcomes were being achieved and McClellan et al. (2006) analysed that even when compared to a doctor, patients with MSK related conditions preferred to see a physiotherapist directly. Despite these boundaries, Taylor et al. (2011) analysed that both patients and fellow staff reported high levels of satisfaction with emergency physiotherapists. The main variation came from staff knowledge regarding the proficiency and scope of emergency physiotherapists of which they (Taylor et al. 2011) investigated. This was particularly true amongst other staff members in the emergency department (Taylor et al. 2001). It appeared [in Australia] there was a general debate as to if physiotherapists were working with an extended scope of practice or if they were just advancing their already established skills. However, in the UK, emergency physiotherapists have been defined as ‘clinical specialists working beyond recognised scope of physiotherapy practice in innovative or non-traditional roles ‘(Crane & Delany, 2013).

Working in newly formed teams can prove difficult for physiotherapists in emergency settings. Inter-disciplinary relationships must be built quickly in a pressurised environment where individuals tend to have more responsibility than other roles (Anaf & Sheppard, 2007; Crane & Delany, 2013) as unlike outpatient and inpatient settings, emergency departments are much less hierarchical resulting in an increased level of duty.

Self assessment questions:

1. What part does physiotherapy in emergency care settings have to play in the 20:20 Vision and AHP National Delivery Plan for Scotland? What proposed benefits will most likely facilitate these strategies?

2. Think back to a previous visit to the accident and emergency department either for yourself or a family member/friend, perhaps before you commenced your physiotherapy career. How would you have felt being treated by professional that was not a doctor? Do you think this would have affected your views of the service provided? Take a few moments to reflect on how you would have reacted in this situation previously compared to how you may react now having read the above information.

Prescribing[edit | edit source]

Description[edit | edit source]

<a href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-18955680">BBC News Article: Prescription Powers</a>

Cost Effectiveness[edit | edit source]

Training/ Qualifications[edit | edit source]

Evidence to support[edit | edit source]

Challenges[edit | edit source]

Injection Therapy[edit | edit source]

Description[edit | edit source]

In the context of physiotherapy practice, injection therapy is the use of selected prescription only medicines (POMs) which are administered via injection to the intra-articular tissues, extra-articular tissues and joint spaces (CSP, 2011). Injection therapy also includes the aspiration of joint spaces.

This particular therapy has been used within physiotherapy practice since 1997 (CSP, 2013), however, within the past 5 years this particular therapy has taken off for therapeutic purposes. The CSP (2013) states the most common areas in which this is used:

- Inflammatory pain from orthopaedic and rheumatic conditions.

- Spasticity and dystonia from neurological conditions.

- Chronic headache from musculoskeletal or neurological origin.

- Bladder disorders in women’s health physiotherapy.

Vaccination, subcutaneous and other parenteral administration of drugs, while being dispensed via injection, are not considered as injection therapy. Physiotherapists must prove themselves to be competent in delivering injections before offering this as part of their practice. They may choose to specialise in anatomical areas or conditions, so this will determine what level of learning they may require to undertake.

Physiotherapists have an added advantage over doctors when administering injections in that they are able to provide the appropriate exercises at the same time to target the muscle groups or joints which are affected by the programme. These exercises can be for very shortly after the steroid injection, for when the flare has settled in the joint to prevent further appointments being made or for both. The patient is then able to go home and safely exercise the area after the injection and may not require further input from physiotherapy or a doctor for that specific problem.

Medications used in Injection Therapy

As mentioned in the introduction, injection therapy has been used in physiotherapy since 1997. The introduction of prescribing rights for physiotherapists recently has increased the means by which physiotherapists can access medicines. In addition, the growth of private physiotherapy providers has required a greater understanding of medicine within non-NHS settings.

The patient specific direction (PSD)

A PSD is an instruction from a prescriber of medicine to be administered to an individually named patient. The physiotherapist must only dispense the medicine in accordance with the instructions provided by the prescriber. Some non-medical independent prescribers, including physiotherapists are permitted to prescribe the mixing of licensed medicines, and can prescribe a differing range of controlled drugs, according to profession.

The Patient Group Direction (PGD)

A senior doctor and pharmacist in union with the physiotherapists, define in writing the named drugs that may be supplied or administered to groups of patients. The PGD must meet specific legal criteria in order to be valid. Only licensed drugs are included in the PGD and the physiotherapist named on the PGD must be registered with the HCPC. The physiotherapist must only supply and administer medicine in accordance with the instructions on the PGD. PGD’s are valid in all NHS hospitals and primary care settings.

Under the terms of the Human Medicines Regulations 2012, mixing two licenced drugs such as a local anaesthetic and a corticosteroid creates a new unlicensed drug which cannot be dispensed under a PGD.

While working under a PGD, physiotherapists must not mix local anaesthetic and corticosteroid in the syringe prior to injection. However, there is a selection of possibilities to consider to comply with law:

- Administer pre-mixed commercially available drugs which are licenced e.g. Depomedrone with Lidocaine.

- Administer two separate injections.

- Do not use local anaesthetic (CSP, 2013).

More information on mixing drugs in clinical practice can be found here.

http://www.nice.org.uk/about/nice-communities/medicines-and-prescribing

In regards to insurance, as per the terms of the CSP’s professional liability insurance scheme, members must practice lawfully within the scope of physiotherapy practice.

Cost Effectiveness[edit | edit source]

With the ever increasing strain upon the NHS due to free healthcare causing excess demand, waiting times to see a general practitioner (GP) can be lengthy and may be an un-necessary process when another allied healthcare professional (AHP) may be able to treat the patient. AHP’s providing injection therapy is a cost effective strategy for the NHS to employ. It enables shorted patient journeys, and in a report by NHS Tayside (2014) has been found to contribute to less GP appointments and reducing orthopaedic waiting lists. Over 99% of patient treated in NHS Tayside with a corticosteroid injection as part of their treatment, were managed solely by AHP’s. A mere 0.06% were appropriately referred to a consultant led service, resulting with a potential saving to NHS Tayside of over £150,000. This is based on a consultation including an injection plus a follow up appointment with a physiotherapist costing £37 for a band 6 physiotherapist, £41.26 for a band 7 physiotherapist and for a consultant to carry out the same procedure, would cost the national health service £227. NHS Tayside administered 798 injections by AHP’s over the 2013-2014 period, which is an increase of 30% on the previous year. 94% of patients reported an improvement in pain scores using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) reporting method. The report indicates great benefits to patient care with an evidence based AHP approach to treatment, combining injection therapy and exercise as part of the care plan. A second study by Jowett et al (2013) found that the mean costs for the NHS for patients receiving were lower in the injection plus exercise group compared with the exercise alone (£261 v £318), as this resolved the problem quicker and entailed a shorter journey through the healthcare system to recovery.

| Band/ role within the NHS |

Cost for consultation, injection and follow up appointment |

| Band 6 Phyiotherapist | £37 |

| Band 7 Physiotherapist | £41.26 |

| Consultant | £227 |

Table 1: Costings from NHS Tayside for injection therapy

With physiotherapists now working in primary care as previously mentioned, and some physiotherapists gaining prescribing rights in the UK also, this is making injection therapy a more accessible and cost effective way for the NHS to save both money and time and have patients seen by the appropriate people.

Training/ Qualifications[edit | edit source]

According to the CSP (2013), initially it was doctors who trained physiotherapists in the injection technique. However, the published educational guidelines produced by the CSP in 2011 expects all physiotherapists who wish to practice injection therapy to meet these set standards. All members should be outfitted with all the abilities required to enable safe injection under a variety of legal frameworks.

If a physiotherapist is under supervision of a doctor as part of the training procedure, the supply and administration of the medicines to patients comes under the framework of a PSD. Another qualified physiotherapist who is competent in injection therapy may supervise the trainee. However, law states that supply and administration of medicines under a PGD cannot be delegated, so the physiotherapist actually administering the injection must be named on the PGD. So if a physiotherapist is supervising the trainee-injector, both parties must be named on the PGD document.

In terms of competence, it is perfectly acceptable for a physiotherapist competent in delivering injection therapy to be involved in teaching doctors injection-therapy techniques (CSP, 2013).

There are a number of routes available to practitioners are able to reach the level of knowledge and skills required to practice injection therapy safely, effectively and competently. These are:

- A higher education institution offering an accredited module.

- A course offered by a professional organisation or network.

- A period of structured work based learning.

The CSP has set out expectations of all routes available to:

1. Enable physiotherapists to achieve outcomes set out in the educational expectations document.

2. Include elements of supervised practice which are overseen by a qualified practitioner in injection therapy which allows trainees to develop knowledge skills in a safe and legal environment.

3. Include assessment of the trainee’s learning.

A large amount of injection therapy includes the use of a corticosteroid to reduce inflammation in a joint. A steroid injection can be administered into the joint space to suppress inflammation in joints and connective tissues, suppress flares in rheumatic joint diseases and can stop the inflammatory response in a soft tissue injury (Tidball, 2013). These are usually administered along side a local anaesthetic to provide an immediate relief from the pain as well as working as pain relief to the steroid injection itself.

Common complications and side effects of the steroid injection can include soreness and bruising at the site of injection, increased pain in the affected area (up to 7 days), light headedness, and less commonly, haematoma, infection at the site of injection, fainting or allergic reaction. They may be contraindicated due to pregnancy, epilepsy, diabetes, if the patient has a cold or fever and are nervous about needles, hospitals or medical practitioners.

Injection therapy is a post-registration activity due to the nature of the job (White, 2011). Since 2011, the CSP has set educational expectations for physiotherapists who wish to partake in injection therapy. Physiotherapists must be able to exhibit 150 hours (20 days) of learning at either level 3 (Bachelor’s) or level 4 (masters) level to ascertain their aptitude in injection therapy.

These educational expectations can be found here.

http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/csp-expectations-educational-programmes-injection-therapy-physiotherapists

Higher education institutions may offer modules in injection therapy which meet the CSP expectations. According to the CSP (2013) the following professional associations provide appropriate training:

- Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Orthopaedic Medicine and Injection Therapy – www.acpomit.co.uk

- Society of Musculoskeletal Medicine – www.sommcourses.org

There are certain pre-requisites which physiotherapists much reach before beginning an injection therapy educational programme. These are:

- Provide evidence of current and valid HPC registration.

- Provide evidence of appropriate insurance to practice.

- Be currently working in a country where injection therapy is considered within the scope of practice.

- Be able to display relevant physiotherapy aptitude, skills and experience in the assessment and diagnosis of clinical conditions which may benefit from injection therapy.

- Be able to identify the benefits to patients in offering injection therapy.

- Have formally identified and entered an agreement with a supervisor for the practice based learning before commencing the course.

- Be practicing in a role or moving into a role where injection therapy is an essential element of practice.

- Have access to the relevant medicines through a setting-appropriate legal medicines framework which are required for injection therapy.

There are also concurrent requirements to injection therapy upon when the physiotherapist completes the programme of learning in injection therapy, the individual must also hold the following in order to practice injection therapy safely:

- Valid CPR/ Basic life support certification.

- Valid anaphylaxis management training (may be offered as part of the course in injection therapy).

- Appropriate Hepatitis B immunisation.

Course content

According to the CSP (2011), programmes must include theoretical and practice-based components, along side a formal assessment of the participant’s learning. The provider of the programme have options as to how they design and deliver the course. However, all programmes must cover the 7 topic areas listed below:

1. Clinical knowledge.

2. Clinical decision making and diagnosis.

3. Pharmacology and therapeutics.

4. Performance of injection therapy and aspiration.

5. Patient information and informed consent.

6. Communication and documentation.

7. Legal aspects of practice (CSP, 2011).

Within physiotherapy practice, the whole process of injection therapy combines the full assessment, diagnosis and reasoning process to ensure the patient is treated most effectively. The focus of programme content being built around the 7 areas noted above should be on enabling participants to develop knowledge and skills within the scope of practice. It should also focus on further developing the current knowledge and skills held by the physiotherapist in line with achieving competence in injection therapy.

The CSP (2011) have stated the 7 broad learning outcomes which physiotherapists who have participated in a programme should be able to demonstrate. It is up to the programme organiser themselves as to how they interpret these outcomes, and formulate their own specific outcomes for the programme:

1. Knowledge and understanding of applied human anatomy, physiology and pathology in the musculoskeletal and/or neurological physiotherapy context.

2. The ability to clinically reason a patients musculoskeletal and/or neurological dysfunction and evaluate a patient’s suitability for injection therapy.

3. Knowledge and understanding of the pharmacology of the medicines used in musculoskeletal and/or neurological injection- therapy and the indications and contraindications for injection therapy.

4. Demonstrate technical proficiency in a range of injection therapy techniques used in musculoskeletal and/or neurological injection therapy, and proficiency in managing emergencies, complications, unexpected effects and aftercare.

5. The ability to communicate effectively with patients with regards to treatment selection and choice, and the integration of injection therapy into a total-rehabilitation plan.

6. The ability to create an accurate record of the injection therapy management delivered, that is shared with all those in involved in the care of the patient.

7. Knowledge and understanding of the regulation and control of medicines as they apply to 1) physiotherapists and 2) the healthcare delivery setting in which the physiotherapist practices or plans to practice.

Evidence of learning

The CSP expects all members who compete a course in injection therapy to keep evidence of the learning they have undertaken to establish and demonstrate competence in the area (CSP, 2011). This should state all topics covered in the programme, the structure of the programme and the learning outcomes in which they were assessed against. They must also hold proof of the successful completion of the course.

Evidence to support[edit | edit source]

Although injection therapy has been around for well over a decade, the recent soar in practitioners becoming competent and qualified has had positive effects on the pressures the NHS is under to deliver shorter waiting times. Hill (2008) wrote an article in the CSP around the injection therapy pioneer and member of the CSP prescribing steering group, Stephanie Saunders.

“The technique did not stand alone but, in the hands of physiotherapists, when combined with usual rehabilitation modalities, injection therapy could cut the amount of treatment needed and make the effects last longer… However, more evidence was needed”.

The paper summarised an audit of injections between 1999-2008. The results showed that there were a total of 1263 injections – 76% were upper limb, with just under half (345) being shoulder sites. They also found that 34% of shoulder injections were repeated. Adverse reactions were also measured, including 2 patients who suffered anaphylaxis, indicating that the injections were on the whole a usually safe with only a small percentage of people suffering from adverse reactions.

Much of the evidence base for injection therapy to be carried out by physiotherapists crosses over with the Primary Care evidence. Physiotherapists seeing patients at an earlier stage enables prompt treatment which may be more effective and can prevent short term problems from evolving into long term conditions (CSP, 2015).

Patient A has a 10 year history of rheumatoid arthritis, however, she does not suffer from regular flare ups. The patient knows when she has a flare up, if it is not medically managed quickly with a corticosteroid injection, the flare up lasts for significantly longer than if it is treated promptly.

Patient A calls her GP who gives her an appointment later in the week to have a consultation and potentially an injection. After the appointment with her GP, she is further referred to a rheumatology physiotherapist. Patient A is then put on a 6 week waiting list for physiotherapy, and by the time the appointment comes around, she has major loss of range of movement and strength in the affected joint, and has to undergo a 12 week physiotherapy programme to rebuild the strength and gain range of movement back.

Patient B is in a similar situation with her medical history however when she calls up the GP practice, she is given an appointment with a primary care physiotherapist for later in the week. At her appointment with the physiotherapist, she has a consultation and injection of corticosteroid into the affected joint. The physiotherapist also provides her with an exercise programme for range of movement of the affected joint, and a strengthening programme for when the flare up settles. She then has a follow up appointment with a rheumatology physiotherapist 3 weeks later and is discharged.

Which would you rather?

Upon speaking to an Advanced Physiotherapy Practitioner who carries out injection therapy while specialising in musculoskeletal and orthopaedic conditions, a career pathway was able to be drawn up. When asked how they had reached their current position, they answered as followed:

“I spent 2 years on basic grade rotations in Secondary Care in Teaching Hospitals. Following this, I spent 18 months on a rotational musculoskeletal speciality where I became a senior II in Secondary Care Teaching Hospitals. From there, I attended various post graduate weekend courses, conferences, lots of reading and experiential learning.

I then spent 2 years as a developmental musculoskeletal specialist spanning both primary and secondary care settings which was a Senior I role paid as a Senior II – the difference in salary was ring fenced and used for professional development. I then completed an MSc in Manual Therapy from Manchester University where I left with MMACP qualification.

I then worked 4 years as a Senior I musculoskeletal specialist in a Primary care setting and I carried out further post-graduate study looking at an RCT involving tendinopathy. I completed further M level modules including Contemporary Practice in Injection Therapy from Nottingham University… I have also published a chapter in Maitland’s Peripheral Manipulation 5th edition where it focuses on shoulder assessment and management from a physiotherapy and ESP perspective. My current position now is an Advanced Physiotherapy Practitioner/ ESP Orthopaedics with specialism and Advanced Physiotherapy Practitioner clinical team lead.”

We asked our source what they enjoyed most about their current position. This was their reply:

“I enjoy the variety of workload and multi-disciplinary team working. I am involved in diagnostic reasoning (biomedical diagnostic reasoning in addition to physiotherapy movement paradigm reasoning). I enjoy supporting staff development and having the opportunity to shape service development and delivery.”

When asked about what advice they would give to current students, new graduates and junior physiotherapists beginning their own journey on to the physiotherapy ladder, they gave this answer:

“Take time to develop a breadth of experience throughout the profession prior to specialising in one area, be a critical and independent thinker, take care when listening to opinion, read, read and read! Understand the underpinning basis of the profession – understand how the profession has developed, where it is now and where it may be headed, be re-assured that it is okay to be confused, LISTEN to your patients and network as much and as often as possible!”

Challenges[edit | edit source]

Some of the challenges in which practitioners may face in becoming qualified in injection therapy may lead back to the issues with funding within the NHS. Physiotherapists must be able to justify why their workplace will benefit from having an AHP qualified in injection therapy. This may be further complicated if there are no other qualified members of staff able to supervise the trainee through the practice based process.

Another challenge which may be faced by therapists when injecting involves the medications themselves. If there was no pre-mixed local anaesthetic and corticosteroid, should the corticosteroid be administered with no local anaesthetic? (Hill, 2008). To mix the two individual substances in a syringe is constituted as making a new substance and is illegal to administer. However, this is permissible if the mixing is done as part of a clinical management plan where a Doctor shares responsibility.

Our Advanced Physiotherapy Practitioner source told of the challenged they had faced in injection therapy:

“Time pressures can cause a challenge on a daily basis. Also, finding a work- life balance can be tricky. Facilitating other professional’s understanding of physiotherapy and ESP/APP roles!”

Self assessment questions:

1. Consider your place of work, or if you are a student, think back to a placement you have had recently. Imagine there was an opportunity for someone on the team to be put forward to become trained and competent in injection therapy. Consider three reasons to try to justify yourself to be put forward for the course?

2.

Humanitarian[edit | edit source]

Description[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists have a critical role in helping people that have been affected by pandemics, natural disasters and other major emergencies. Physiotherapists need to be engaged at an organizational level so that they can provide appropriate services to affected communities and areas by saving lives and improving outcomes for survivors of these emergencies.

The WCPT encourages engagement of physiotherapists when disasters of all sorts strike. Physiotherapists should

- be involved in developing ideas and policies that helps communities, areas, and towns prepare for disasters

- be involved in preventative measures and education throughout the disaster, also before and especially after

- provide appropriate treatment, intervention and rehabilitation to survivors

- ensure that areas have adequate access to appropriate physiotherapy treatment/interventions which includes rehabilitation to achieve best possible care for their needs.

- Prepare by learning about risks and preventions strategies to react to disasters from home, work and different environment settings

- Give particular attention to, and raise awareness for certain groups like elderly and disability groups at times of disaster

Taken from the CSP website : http://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/gaza-alert-physiotherapy-humanitarian-response,

Zoe Clift who is an extended scope practitioner and St Thomas hospital in London explained a typical day working in the Israel:

7am - At Handicap International (HI) office for security brief

9am - Meet with Rafah area team to start clinical visits. First patient (median nerve and flexor tendon injury) assessment/treatment plan completed by local Gaza team with only reassurance needed from us – fantastic to see the progress in their clinical skills and their growing confidence.

10am - Second clinical visit (median nerve and tibial ex-fix, plus patient’s son with head injury). Local physio points out where he lives amid the rubble ... a reminder for me of the situation the clinicians are living and working in.

12.30pm - Visit nine-year-old girl, arranged specifically for review of possible lower limb peripheral nerve injury and wound/dressing review. Referred to me and Lesley (major trauma nurse) as local therapy team all male. Simple clinical session gaining patient trust – emotionally this is probably the toughest case we have seen.

13.30pm - Debrief with Rafah team. Reassured them they are doing a fantastic job at learning new skills and applying them. Brilliant to feel we are leaving them with tools to continue.

3pm - Final mission de-brief at HI office. Extremely positive feedback. We agree to continue work to provide plan/guidance for next time – it’s not ‘if’ but ‘when

Speaking at the Physiotherapy UK conference and trade exhibition in Liverpool on the 16-17 of October, Peter Skelton, talked about the role of rehabilitation professionals responding to humanitarian emergencies and how it is becoming increasingly recognisable around the globe.

He informed that for the first time, physiotherapists were being initiated into emergency medical teams such as UKIETR. This new emerging role is being led by the World Health organisation (WHO) and in the UK, they are building its professional capacity to respond to emergencies via the UKIETR. This includes the training and recruitment of medical and allied health professionals by UK – Med and save the children.

Members will receive full training in humanitarian response, funding for the project and also backfill payments into the NHS. Handicap international have facilitated the recruitment of RP’s to the UKIETR. From this they have developed a rehabilitation specific training in collaboration with 10 different professional networks in the UK. They have developed theoretical and practical training components covering spinal cord injury, amputation, fracture, burns, nerve injury and soft tissue injury. The involvement of the professional networks is crucial as it ensures training is based on current best practice and gathers input form the UK’s leading clinicians.

At this present time, 63 rehabilitation professionals are on the register. One physiotherapist has been deployed to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines and 9 physiotherapists have been deployed to the Gaza crisis to treat patients and to provide specialised education to local health professionals.

Peter Skelton concluded that this is the first time specialised humanitarian training has become available to those who wish to work within humanitarian emergencies. However he believes there still needs to be an improvement in recruitment of physiotherapists who are highly skilled in trauma.

Doctors without borders are a group of health professionals which help people deal with the complications of war. They are a international humanitarian organisation who are best known for their contribution in war - torn regions and developing countries. At this present times, they have 60 on-going projects around the world. Their main aim is to provide healthcare support to those needed, however they also carry out research to provide evidence which supports the healthcare they are providing.

Here is a video showing the work doctors without borders do when dealing with a natural disaster:

<img class="FCK__MWTemplate" src="http://www.physio-pedia.com/extensions/FCKeditor/fckeditor/editor/images/spacer.gif" _fckfakelement="true" _fckrealelement="1" _fck_mw_template="true">

Cost Effectiveness[edit | edit source]

Volunteering[edit | edit source]

If you wish to be involved in a disaster area it is very important that it is done through an established group as opposed to doing it alone. Having different numerous individuals and small groups getting involved can be problematic as opposed to supportive. Usually governments have their own administrations and agencies working to capacity which is why they are unable to deal with individual volunteers. A list of organizations involved in relief programs can be found <a href="http://www.wcpt.org/node/36994">here</a>.

Sometimes these organisatinos assemble teams to serve in a particular area for week, sometimes even months. Careful planning and consideration by the individual physiotherapist needs to be taken to see if this is appropriate for the individual. Sometimes groups ask volunteers to make a 3 month commitment and often more on particular disasters.

Training/ Qualifications[edit | edit source]

Veterans international are a international humanitarian group that address the effects and consequences of war that has gone on in Cambodia. To apply to work with Veterans international you have to have the following :

•Have a Bachelors Degree in Physiotherapy or a related subject then you will be suited for this project.

•Ideally, a qualified physiotherapist would also possess at least two years’ experience of practicing professionally.

Evidence to support[edit | edit source]

Challenges[edit | edit source]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from <a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/">Pubmed</a>)[edit | edit source]

Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see <a href="Adding References">adding references tutorial</a>. <span class="fck_mw_references" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="references" /></div>