Proprioception

Original Editor - The Open Physio project.

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Admin, Amanda Ager, Kim Jackson, Vanessa Rhule, Paule Morbois, Scott Buxton, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Rishika Babburu, Rachael Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Claire Knott, Amrita Patro and Wanda van Niekerk

Introduction[edit | edit source]

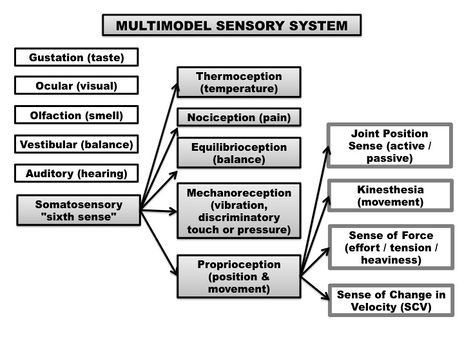

Proprioception (sense of proprioception) is an important bodily neuromuscular sense. It falls under our "sixth sense", more commonly known as somatosensation. The term somatosensation (or somatosensory senses) is an all encompassing term which includes the sub-categories of mechanoreception (vibration, pressure, discriminatory touch), thermoreception (temperature), nociception (pain), equilibrioception (balance) and proprioception (sense of positioning and movement).[1] The feedback from all these different sensory components arise from our peripheral nervous system (PNS), and feed information to our central nervous system (CNS), both at the level of the spinal cord (reflexive) and sent to the cerebral cortex for higher processing.[2]

Proprioception itself can be understood as including various sub-modalities:

Proprioception (Joint Position Sense): Proprioception is our sense of joint / limb positioning. It is often measured through joint position sense - active joint position sense (AJPS) and passive joint position sense (PJPS). Joint position sense determines the ability of a person to perceive a presented joint angle and then, after the limb has been moved, to actively or passively reproduces the same joint angle[3] (Clinically measured as a joint matching task).

Kinaesthesia: Kinaesthesia (kinaesthesis) is the awareness of motion of the human body (motion sense).[4] Sense of movement refers to the ability to appreciate joint movement, including the duration, direction, amplitude, speed, acceleration and timing of movements.[3]

Sense of Force: Sense of Force (SoF) is also known as sense of effort / heaviness / tension or the force matching sense. It is the ability to reproduce (or match) a desired level of force one or more times. Sense of force is thought to stem from the afferent feedback of the Golgi Tendon Organs (GTOs) embedded within our tendons, the muscle spindles within our muscles and proprioceptions within our skin.[5]

Sense of Change in Velocity (SoV): SoV is our ability to detect vibration, derived from oscillating objects placed against the skin.[6] It is believed to travel through the same type of large afferent nerve fibers (Aαβ) as proprioception.[7]

Globally, all sub-modalities of proprioception arise from the sum of neural inputs from the joint capsules, ligaments, muscles, tendons, and skin, in a multifaceted system, which influences behavior regulation and motor control of the body.[8]

Proprioception is critical for meaningful interactions with our surrounding environment. Proprioception helps with the planing of movements, sport performance, playing a musical instrument and ultimately helping us avoid an injury.

The neurological basis of proprioception comes primarily from sensory receptors (mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors) located in your skin, joints, and muscles (muscle spindles with a smaller component from tendon organ afferents, cutaneous receptors and minimal input from joint receptors). These muscle afferents receptors allow for the identification of limb position and movement via neural signalling of a change in muscle, skin or joint stretch[9]. Hence, proprioception is basically a continuous loop of feedforward and feedback inputs between sensory receptors throughout your body and your nervous system.

The short video below gives a good insight into the complexities of proprioception.

Causes of Proprioception Impairment[edit | edit source]

Poor proprioception at a joint may result in the increased likelihood of an injury.[11]

Some things can affect proprioception.

- Temporary impairment can come from eg drinking too much alcohol

- Age-related changes also affect proprioception. The risk of proprioception loss increases as we age due to a combination of natural age-related changes to the nerves, joints, and muscles.

- Injuries or medical conditions that affect the muscles, nerves, and the brain can cause long-term or permanent proprioception impairment. See below

Neurological disorders: eg brain injuries; multiple sclerosis (MS); stroke; Parkinson’s disease; Huntington’s disease; ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis)

Health conditions eg. herniated disc; arthritis; autism spectrum disorder (ASD); diabetes; peripheral neuropathy

Surgery eg. joint injuries, such as an ankle sprain or knee sprain; joint replacement surgery, such as hip replacement or knee replacement

Assessing Proprioception[edit | edit source]

A proprioception disorder or injury could cause a number of signs and symptoms.

Subjective assessment should include questions regarding the following

- balance issues, such as having trouble standing on one foot or frequent falls while walking or sitting

- uncoordinated movement, such as not being able to walk in a straight line

- avoiding certain activities, such as climbing stairs or walking on uneven surfaces because of a fear of falling

Objective assessment should include observation of the above and the points below

- clumsiness, such as dropping or bumping into things

- poor postural control, such as slouching or having to place extra weight on a table for balance while sitting

- trouble recognizing your own strength, eg pressing on a pen too hard when writing or not being able to gauge the force needed to pick something up

There are several means by which physiotherapists can assess proprioception, depending on the body part being assessed. The include:

- Romberg test

- Heel-shin. The patient is asked to touch the heel of one foot to the opposite knee and then to drag their heel in a straight line all the way down the front of their shin and back up again. In order to eliminate the effect of gravity in moving the heel down the shin, this test should always be done in the supine position.

- Ataxia. Best revealed if the examiner's finger is held at the extreme of the patient's reach, and if the examiner's finger is occasionally moved suddenly to a different location.

- Finger—nose—finger test. The patient is asked to alternately touch their nose and the examiner's finger as quickly as possible

- Walking in a straight line

- Distal proprioception test. The tester will move the joints of the hip, knee ankle and big toe up and down while you watch. You then ask the client to repeat the same movement with your eyes closed.

Learning New Skills[edit | edit source]

Proprioception is what allows someone to learn to walk in complete darkness without losing balance. During the learning of any new skill, sport, or art, it is usually necessary to become familiar with some proprioceptive tasks specific to that activity. Without the appropriate integration of proprioceptive input, an artist would not be able to brush paint onto a canvas without looking at the hand as it moved the brush over the canvas; it would be impossible to drive an automobile because a motorist would not be able to steer or use the foot pedals while looking at the road ahead; a person could not touch type or perform ballet; and people would not even be able to walk without watching where they put their feet.

Physiotherapy - Training Proprioception[edit | edit source]

No matter the underlying cause physiotherapists can train clients with activities to improve motor skills, strength, and balance. Also they can help clients to learn how to manage daily tasks while living with proprioception dysfunction.

There is converging evidence that proprioceptive training can yield meaningful improvements in somatosensory and sensorimotor function[12]. Retraining of somatosensory function includes any interventions that addresses the remediation of the somatosensory modalities. Intervention methods include: education; repetitive practice and feedback in detecting, localising, discriminating, or recognising different sensory stimuli, pressure, or objects; proprioceptive training; balance training and somatosensory stimulation[13].

A 2019 review on Sensory retraining of the leg after stroke concluded that interventions used for retraining leg somatosensory impairment after stroke significantly improved somatosensory function and balance but not gait[13].

A 2005 systematic review of the Effect Of Proprioceptive and Balance Exercises on People With an Injured Or Reconstructed Anterior Cruciate Ligaments reported that proprioceptive and balance exercise improves outcomes in individuals with ACL-deficient knees[14]. Similarly a 2015 review of The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations concluded that proprioceptive training programmes are effective at reducing the rate of ankle sprains in sporting participants, particularly those with a history of ankle sprain[15]

The effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment on balance dysfunction and postural instability in persons with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2016 reported that physiotherapy interventions like balance training combined with muscle strengthening, range of movement and walking training exercise is effective in improving balance in patients with Parkinson’s disease. As propriocetion is part of balance training this would advocate proprioceptive retraining[16].

Techniques include

- exercises, such as balance exercises. Standing on a Balance board is often used to retrain or increase proprioception abilities, particularly as physical therapy for ankle or knee injuries.

- Tai Chi, which improves lower limb proprioception and Yoga, which improves balance and muscle strength. The slow, focused movements of Tai Chi practice provide an environment whereby the proprioceptive information being fed back to the brain stimulates an intense, dynamic "listening environment" to further enhance mind / body integration.

- somatosensory stimulation training, such as vibration therapy

See these great pages too

Neuromuscular Exercise Program

Developmental Coordination Disorder and Physical Activity

Sensorimotor Impairment in Neck Pain

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ager, A.L., Borms, D., Deschepper, L., Dhooghe, R., Dijkhuis, J., Roy, J.S., & Cools, A.Proprioception and shoulder pain: A Systematic Review. J Hand Ther. 2019 Aug 31. pii: S0894-1130(19)30094-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2019.06.002.

- ↑ Guyton AC. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA WB Saunders; 1992.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Riemann, B. L., & Lephart, S.M. (2002). The sensorimotor system, part 1: the physiological basis of functional joint stability. Journal of Athletic Training, 37(1),71-79.

- ↑ Sherrington CS. On the proprio-ceptive system, especially in its reflex aspect. Brain. 1907;29:467–482.

- ↑ Hung, Y. J. (2015). Neuromuscular control and rehabilitation of the unstable ankle. World Journal of Orthopedics, 6(5), page 434.

- ↑ Gilman, S., Joint position sense and vibration sense: anatomical organisation and assessment.Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 2002. 73(5): p. 473-7.

- ↑ Shakoor, N., A. Agrawal, and J.A. Block, Reduced lower extremity vibratory perception in osteoarthritis of the knee.Arthritis and rheumatism, 2008. 59(1): p. 117-21.

- ↑ Blanche, E.I., Bodison, S., Chang, M.C., & Reinoso, G. (2012). Development of the Comprehensive Observations of Proprioception (COP): Validity, Reliability, and Factor Analysis. Am J Occup Ther. 66(6): 691–698. doi:10.5014/ajot.2012.003608.

- ↑ Suetterlin KJ, Sayer AA. Proprioception: where are we now? A commentary on clinical assessment, changes across the life course, functional implications and future interventions. Age and ageing. 2013 Nov 14;43(3):313-8. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ageing/article/43/3/313/16765 (last accessed 31.10.19)

- ↑ W Deloriea Proprioceptors Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dzlkz8j-8rg ( last accessed 30.10.2019)

- ↑ Anderson, V. B., & Wee, E. (2011). Impaired joint proprioception at higher shoulder elevations in chronic rotator cuff pathology. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 92(7), 1146-1151. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.02.004

- ↑ Aman JE, Elangovan N, Yeh I, Konczak J. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training for improving motor function: a systematic review. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2015 Jan 28;8:1075. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4309156/ (last accessed 31.10.2019)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Chia FS, Kuys S, Low Choy N. Sensory retraining of the leg after stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical rehabilitation. 2019 Jun;33(6):964-79. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0269215519836461 (last accessed 31.10,2019)

- ↑ Cooper RL, Taylor NF, Feller JA. A systematic review of the effect of proprioceptive and balance exercises on people with an injured or reconstructed anterior cruciate ligament. Research in sports medicine. 2005 Apr 1;13(2):163-78. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15438620590956197 (last accessed 31.10.2019)

- ↑ Schiftan GS, Ross LA, Hahne AJ. The effectiveness of proprioceptive training in preventing ankle sprains in sporting populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2015 May 1;18(3):238-44. Available from: https://www.jsams.org/article/S1440-2440(14)00074-7/fulltext (last accessed 31.10.2019)

- ↑ Yitayeh A, Teshome A. The effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment on balance dysfunction and postural instability in persons with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC sports science, medicine and rehabilitation. 2016 Dec;8(1):17. Available from: https://bmcsportsscimedrehabil.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13102-016-0042-0 (last accessed 31.10.2019)