Posture

Introduction [edit | edit source]

Posture is the term used to describe the alignment of the body and its position in space and is influenced by many factors either when stationary or in motion. Posture is achieved through the coordinated action of various muscles working to maintain stability[1]. Posture can be categorised as inactive or active:[2][3]

- Inactive- Describes the posture of the body when it is at rest and fully supported without moving, for example sleeping. The body is in a state of relaxation or under tension (by using stretched ligaments for support) and there is minimal muscle activity.

- Active- Active postures can either be static or dynamic. It requires the integration and coordination of many muscles to maintain active postures, they are basically divided into two type and can be either:

- Static postures- Body segments are aligned and maintained in fixed positions. This is usually achieved by co-ordination and interaction of various muscle groups which are working statically to counteract gravity and other forces. Examples of static postures are standing, sitting, lying, and kneeling.

- Dynamic postures- In this type of posture body segments are moving. it is usually required to form an efficient basis for movement. Muscles and non-contractile structures have to work to adapt to changing circumstances. Examples are walking, running, jumping, throwing, and lifting.

- Static postures- Body segments are aligned and maintained in fixed positions. This is usually achieved by co-ordination and interaction of various muscle groups which are working statically to counteract gravity and other forces. Examples of static postures are standing, sitting, lying, and kneeling.

Posture Assessment[edit | edit source]

In an ideal posture, the line of gravity should pass through specific points of the body. This can simply be observed or evaluated using a plumb line to assess the midline of the body. This line should pass through the lobe of the ear, the shoulder joint, the hip joint, though the greater trochanter of the femur, then slightly anterior to the midline of the knee joint and lastly anterior to the lateral malleolus. When viewed from either the front or the back, the vertical line passing through the body's centre of gravity should theoretically bisect the body into two equal halves, with the bodyweight distributed evenly between the two feet.

In assessing posture, symmetry and rotations/tilts should be looked out for in the anterior, lateral and posterior views. Assess:

- Head alignment

- Cervical, thoracic and lumbar curvature

- Shoulder level symmetry

- Pelvic symmetry

- Hip, knee and ankle joints

In sitting:

- The ears should be aligned with the shoulders and the shoulders aligned with the hips

- The shoulders should be relaxed and elbows are close to the sides of the body

- The angle of the elbows, hips and knees is approximately 90 degrees

- The feet flat on the floor

- The forearms are parallel to the floor with wrists straight

- Feet should rest comfortably on a surface

Muscle Action in Posture[edit | edit source]

The balanced posture of the body reduces the work done by the muscles in maintaining it in an erect posture. It has been determined (using electromyography) that, in general[4]:

- The intrinsic muscles of the feet are quiescent, because of the support provided by the ligaments.

- Soleus is constantly active because gravity tends to pull the body forward over the feet. Gastrocnemius and the deep posterior tibial muscles are less frequently active.

- Tibialis anterior is less active (unless high heels are being worn).

- Quadriceps and the Hamstrings are generally not as active[5].

- Iliopsoas is constantly active.

- Gluteus maximus is inactive.

- Gluteus medius and tensor fascia latae are active to counteract lateral postural sway.

- Erector spinae is active, counteracting gravity's pull forwards.

- The abdominal muscles remain quiescent, although the lower fibres of the Internal obliques are active in order to protect the inguinal canal

Fixed Support Strategies[edit | edit source]

Ankle[edit | edit source]

| Forward translation of support surface

(backward motion of the body) |

Backward motion of the support surface

(forward motion of the body) |

|---|---|

| Muscles distal to proximal | Muscles distal to proximal |

| Tibialis anterior | Gastrocnemius |

| Quadriceps femoris | Hamstrings |

| Abdominals(neck flexors) | Paraspinals(neck extensors) |

Hip[edit | edit source]

| Forward translation of support surface

(backward motion of the body |

Backward motion of the support surface

(forward motion of the body) |

|---|---|

| Abdominals | Paraspinals |

| Quadriceps femoris | Hamstrings |

| Tibialis anterior | Gastrocnemius |

Examples of Types of Standing Posture[edit | edit source]

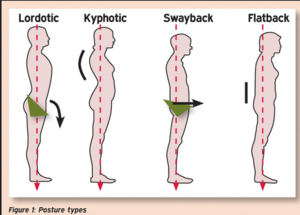

Some of the examples of faulty posture can be as follows:

- Lordotic posture- Lordosis refers to the normal inward curvature of the spine. When this curve is exaggerated it is usually referred to as hyperlordosis. The pelvis is usually tilted anteriorly.

- Sway Back Posture- In this type of posture, there is forward head, hyper-extension of the cervical spine, flexion of the thoracic spine, lumbar spine extension, posterior tilt of the pelvis, hip and knee hyper-extension and ankle slightly plantarflexed.

- Flat back posture- In this type of posture, there is forward head, extension of the cervical spine, extension of the thoracic spine, loss of lumbar lordosis and posterior pelvic tilt.

- Forward head posture - Describes the shift of the head forward with the chin poking out. It is caused by increased flexion of the lower cervical spine and upper thoracic spine with increased extension of the upper cervical spine and extension of the occiput on C1.

- Scoliosis - This is a 3 dimensional C or S shaped sideways curve of the spine

- Kyphosis - An increased convex curve observed in the thoracic or sacral regions of the spine.

The Relationship Between Posture and Pain[edit | edit source]

There are many theories that bad posture is a contributing factor in low back pain[6] but the evidence is poor and the common theory is that it is sustained bad postures that lead to pain[7]. Rather than posture itself it may be the load or the feedback mechanism that causes pain.[8] However some studies have shown that improved posture and postural control can have a positive effect on pain.[9] It is obvious from the lack of consensus that more research is needed before a definitive conclusion can be reached.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Gardiner MD. The principles of exercise therapy. Bell; 1957.

- ↑ Levangie PK, Norkin CC. Joint structure and function: a comprehensive analysis. FA Davis; 2011 Mar 9.

- ↑ Howorth MB. Posture in adolescents and adults. The American journal of nursing. 1956 Jan 1:34-6.

- ↑ Chiba R, Takakusaki K, Ota J, Yozu A, Haga N. Human upright posture control models based on multisensory inputs; in fast and slow dynamics. Neuroscience research. 2016 Mar 1;104:96-104.

- ↑ Tikkanen O, Haakana P, Pesola AJ, Häkkinen K, Rantalainen T, Havu M, Pullinen T, Finni T. Muscle activity and inactivity periods during normal daily life. PloS one. 2013;8(1).

- ↑ Balague F, Troussier B, Salminen JJ. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. Eur Spine J 1999: 6: 429–438

- ↑ Widhe T. Spine: posture, mobility and pain. A longitudinal study from childhood to adolescence. European Spine Journal. 2001 Apr 1;10(2):118-23.

- ↑ Knight JF, Baber C. Neck muscle activity and perceived pain and discomfort due to variations of head load and posture. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 2004 Feb 1;75(2):123-31.

- ↑ Laird RA, Kent P, Keating JL. Modifying patterns of movement in people with low back pain -does it help? A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:169.