Plantar Fasciitis: Difference between revisions

Elien Lebuf (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m (Reverted edits by Elien Lebuf (talk) to last revision by Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

'''Topic Expert''' - [[User:Kris Porter|Kris Porter]] | '''Topic Expert''' - [[User:Kris Porter|Kris Porter]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== | == Definition/Description == | ||

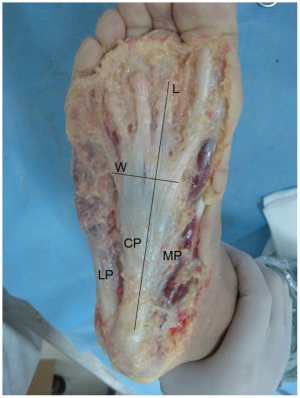

[[Image:Plantar fascia 1.jpg|thumb|right|Axial view of the plantar fascia. LP, lateral part; CP, central part; MP, medial part; L, length; W, width. Chen D-w, Li B, Aubeeluck A, Yang Y-f, Huang Y-g, et al. (2014) Anatomy and Biomechanical Properties of the Plantar Aponeurosis: A Cadaveric Study. PLoS ONE]]Plantar fasciitis may be referred to as plantar fasciosis, plantar heel pain, plantar fascial fibramatosis, among others. Because many cases diagnosed as “plantar fasciitis” are not inflammatory conditions, this condition may be best referred to as "plantar fasciosis." This is confirmed through histological analysis which demonstrates plantar fascia fibrosis, collagen cell death, vascular hyperplasia, random and disorganized collagen, and avascular zones.<ref>Lemont H, Ammirati KM, Usen N. Plantar fasciitis: a degenerative process (fasciosis) without inflammation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93(3):234–7.</ref> There are many different sources of pain in the plantar heel besides the plantar fascia, and therefore the term "'''Plantar Heel Pain'''" serves best to include a broader perspective when discussing this and related pathology. <br> | |||

== Anatomy == | |||

== | The plantar fascia is co<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">mprised of white longitudinally organized fibrous connective tissue which originates on the periosteum of the medial calcaneal tubercle, w</span><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">here it is thinner but it extends into a thicker central portion. The thicker central portion of the plantar fascia then extends into five bands surrounding the flexor tendons as it passes all 5 metatarsal heads. Pain in the plantar fascia can be insertional and/or non-insertional and may involve the larger central band, but may also include the medial and lateral band of the plantar fasica. The plantar fascia is best referred to as fascia because of it's relatively variable fiber orientation as opposed to the more linear fiber orientation of </span>'''aponeurosis'''<span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. The plantar fascia blends with the paratenon of the Achilles tendon, the intrinsic foot musculature and even the skin and subcutaneous tissue.</span><ref>Carlson RE, Fleming LL, Hutton WC. The biomechanical relationship between the tendoachilles, plantar fascia and metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion angle. Foot ankle Int / Am Orthop Foot Ankle Soc [and] Swiss Foot Ankle Soc. 2000;21(1):18–25.</ref><ref>Stecco C, Corradin M, Macchi V, et al. Plantar fascia anatomy and its relationship with Achilles tendon and paratenon. J Anat. 2013;223(August):1–12. doi:10.1111/joa.12111.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;"> The thick viscoelastic multilobular fat pad is responsible for absorbing up to 110% of body weight during walking and 250% during running and deforms most during barefoot walking vs. shod walking.</span><ref>Gefen A, Megido-Ravid M, Itzchak Y. In vivo biomechanical behavior of the human heel pad during the stance phase of gait. J Biomech. 2001;34:1661–1665. doi:10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00143-9</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;"> </span> <br> | ||

During weight-bearing, the tibia loads the the foot “truss” and creates tension through the plantar fascia ('''see image_pending'''). The tension created in the plantar fascia adds critical stability to a loaded foot with minimal muscle activity. Evidence of the important stabilizing nature of the plantar fascia is evidence when following cases post surgical releas which may lead to midfoot arthritis, rupture of the secondary stabilizers of the arch (e.g spring ligament) , as well as other pathologies.<ref>Tweed JL, Barnes MR, Allen MJ, Campbell J a. Biomechanical consequences of total plantar fasciotomy: a review of the literature. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009;99(5):422–30.</ref><ref>Cheung JT-M, An K-N, Zhang M. Consequences of partial and total plantar fascia release: a finite element study. Foot ankle Int / Am Orthop Foot Ankle Soc [and] Swiss Foot Ankle Soc. 2006;27(2):125–32. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16487466.</ref><ref>Crary JL, Hollis JM, Manoli A. The effect of plantar fascia release on strain in the spring and long plantar ligaments. Foot ankle Int / Am Orthop Foot Ankle Soc [and] Swiss Foot Ankle Soc. 2003;24(3):245–50</ref> <br> | |||

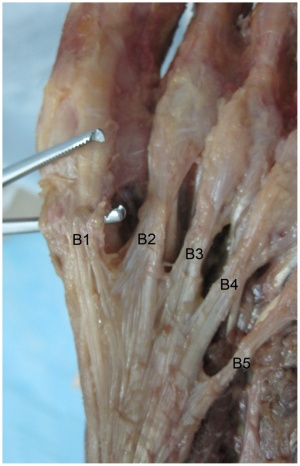

[[Image:Plantar fascia 2.jpg|thumb|left]]<br> | |||

<br> | |||

== Epidemiology & Etiology == | |||

== | <span style="line-height: 1.5em;">The average plantar heel pain episode lasts longer than 6 months and it affects up to 10-15% of the population. However, approximately 90% of cases are treated successfully with conservative care.<ref name="10.2519/jospt.2008.0302">McPoil TG, Martin RL, Cornwall MW, Wukich DK, Irrgang JJ, Godges JJ. Heel pain--plantar fasciitis: clinical practice guildelines linked to the international classification of function, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(4):A1–A18. doi:10.2519/jospt.2008.0302.</ref><ref name="isk factors for Plantar fasciitis">Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for Plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(5):872–7</ref><ref name="10.1053/j.jfas.2010.01.001">Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline-revision 2010. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(3 Suppl):S1–19. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2010.01.001</ref> Although this condition is seen in all ages, it is most commonly expereinced during middle age. Females present with plantar heel slightly more commonly than males and occurs more frequently in an athletic population such as running, accounting for up to 8-10% of all running related injuries.<ref>Lopes AD, Hespanhol Júnior LC, Yeung SS, Costa LOP. What are the main running-related musculoskeletal injuries? A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2012;42(10):891–905. doi:10.2165/11631170-000000000-00000.</ref> In the US alone, there are estimates that this disorder generates up to 2 million patient visits per year, and account for 1% of all visits to orthopedic clinics. Plantar heel pain is the most common foot condition treated in physical therapy clinics and accounts for up to 40% of all patients being seen in podiatric clinics.<ref>2002 Podiatric Practice Survey. Statistical results. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93(1):67–86. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12533562.</ref></span> | ||

= | <span style="line-height: 1.5em;"> | ||

</span> | |||

There are many risk factors which contribute to plantar heel pain including but not limited too: | |||

*Loss of ankle dorsiflexion (talocrural joint, deep or superficial posterior compartment) | |||

*Pes cavus OR pes planus deformities | |||

*Excessive foot pronation dynamically | |||

*Impact/weight bearing activities such as prolonged standing, running, etc | |||

*Improper shoe fit | |||

*Elevated BMI > kg/m<sup>2</sup> | |||

*Diabetes Mellitus (and/or other metabolic conditions)<br> | |||

[[Image:Plantar Windlass mechanism.gif|thumb|right]]<br> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

Heel pain | *Heel pain with first steps in the morning or after long periods of non-weight bearing | ||

*Tenderness to the anterior medial heel | |||

*limited dorsiflexion and tight achilles tendon | |||

*a limp may be present or may have a preference to toe walking | |||

*pain is usually worse when barefoot on hard surfaces and with stair climbing | |||

*many patients may have had a sudden increase in their activity level prior to the onset of symptoms | |||

== Differential Diagnosis<br> == | == Differential Diagnosis<br> == | ||

'''Neurological''' - abductor digiti quinti nerve entrapment, lumbar spine disorders, problems with medial calcaneal branch of the posterior tibial nerve, [[Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome|tarsal tunnel syndrome]]<br> | |||

'''Soft tissue''' - [[Achilles_Tendonitis|achilles tendonitis}], fat pad atrophy, heel contusion, plantar fascia rupture, posterior tibial tendonitis, retrocalcaneal bursitis<br> | |||

'''Skeletal''' - Sever's disease, [[Calcaneal Fractures|calcaneal stress fracture]], infections, inflammatory arthropathies, subtalar arthritis<br> | |||

'''Miscellaneous''' - metabolic disorders, osteomalacia, [[Paget's Disease|Paget's disease]], sickle cell disease, tumors (rare), vascular insufficiency,Rheumatoid arthritis | |||

''For further characteristics on each of these conditions, click on the Cole et al article below'' | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | |||

== | |||

The clinical examination will take under consideration a patient's medical history, physical activity, foot pain symptoms and more. The doctor may decide to use | Plantar fasciitis is a clinical diagnosis. It is based on patient history and physical exam. Patients can have local point tenderness along the medial tuberosity of the os calcis, pain on the first steps or after training. Plantar facia pain is especially evident upon dorsiflexion of the patients pedal phalanges, which further stretches the plantar fascia. Therefore, any activity that would increase stretch of the plantar fascia, such as walking barefoot without any arch support, climbing stairs, or toe walking can worsen the pain. The clinical examination will take under consideration a patient's medical history, physical activity, foot pain symptoms and more. The doctor may decide to use Imaging studies like radiographs, diagnostic ultrasound and MRI. | ||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

The [[Foot and Ankle Ability Measure|FAAM]], or Foot and Ankle Ability Measure, is a good outcome measure to give to patients that are diagnosed with plantar fascitis. | |||

A few studies have also used the Foot Function Index but only the the pain subscale. It is a validated measure, and the first 7 items of the pain subscale are used as the primary numeric outcome measure. Items are scored from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) depending on the mark on the visual analog scale. The sum of the 7 items is then expressed as a percentage of maximum possible score, ranging in an overall percentage. | |||

== Examination == | |||

The clinical examination will take under consideration a patient's medical history, physical activity, foot pain symptoms and more. The doctor may decide to use Imaging studies like radiographs, diagnostic ultrasound and MRI. | |||

* | *Fabrikant et al could conclude that office-based ultrasound can help diagnose and confirm plantar fasciitis/fasciosis through the measurement of the plantar fascia thickness. Because of the advantages of ultrasound-that it is non-invasive with greater patient acceptance, cost effective and radiation-free-the imaging tool should be considered and implemented early in the diagnosis and treatment of plantar fasciitis/fasciosis. <ref name="15">Fabrikant JM et al; Plantar fasciitis (fasciosis) treatment outcome study: Plantar fascia thickness measured by ultrasound and correlated with patient self-reported improvement; Foot (Edinb). 2011 Mar 11. [Epub ahead of print] (level 3)</ref> (level 3) | ||

*Sutera et al found that imaging the ankle/hind foot in the upright weight-bearing position with a dedicated MR scanner and a dedicated coil might enable the identification of partial tears of the plantar fascia, which could be overlooked in the supine position. <ref name="16">Sutera R et al; Plantar fascia evaluation with a dedicated magnetic resonance scanner in weight-bearing position: our experience in patients with plantar fasciitis and in healthy volunteers; Radiol Med. 2010 Mar;115(2):246-60. Epub 2010 Feb 22. (level 3)</ref> (level 3) | |||

*Risk factors to look for by the examination of plantar fasciitis are: | |||

*Reduced ankle dorsiflexion | |||

* | *Obesity | ||

* | *Work-related weight-bearing | ||

* | *Reduced ankle dorsiflexion appears to be the most important risk factor. | ||

== Medical Management <br> == | == Medical Management <br> == | ||

When conservative measures fail, surgical plantar fasciotomy with or without heel spur removal may be employed. There is a method, through an open procedure, percutaneously or most common endoscopically, that releases the plantar fascia. This is an effective treatment, without the need for removal of a calcaneal spur, when present. There is a professional consensus, 70-90% of heel pain patients can be managed by non-operative measures. Surgery for plantar fasciitis should be considered only after all other forms of treatment have failed. With an endoscopic plantar fasciotomy, using the visual analog scale, the average post-operative pain was improved from 9.1 to 1.6. For the second group (ESWT), using the visual analog scale the average post-operative pain was improved from 9 to 2.1. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy gives better results than extra-corporeal shock wave therapy, but with liability of minor complications.<ref>JG Furey, Plantar fasciitis. The painfull heel syndrome, The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 57:672-673 (2010)</ref> <ref>Ahmed Mohamed Ahmed Othman – Ehab Mohamed Ragab, Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy versus extracorporeal shock wave therapy for treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis, Orthopaedic surgery (2009)</ref> | |||

When conservative measures fail, surgical plantar fasciotomy with or without heel spur removal may be employed. There is a method, through an open procedure, percutaneously or most common endoscopically, that releases the plantar fascia. This is an effective treatment, without the need for removal of a calcaneal spur, when present. There is a professional consensus, 70-90% of heel pain patients can be managed by non-operative measures. Surgery for plantar fasciitis should be considered only after all other forms of treatment have failed. With an endoscopic plantar fasciotomy, using the visual analog scale, the average post-operative pain was improved from 9.1 to 1.6. For the second group (ESWT), using the visual analog scale the average post-operative pain was improved from 9 to 2.1. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy gives better results than extra-corporeal shock wave therapy, but with liability of minor complications. | |||

== Physical Therapy Management <br> == | == Physical Therapy Management <br> == | ||

| Line 92: | Line 96: | ||

The most common treatments include stretching of the gastroc/soleus/plantar fascia, orthotics, ultrasound, iontophoresis, night splints, joint mobilization/manipulation, and surgery. | The most common treatments include stretching of the gastroc/soleus/plantar fascia, orthotics, ultrasound, iontophoresis, night splints, joint mobilization/manipulation, and surgery. | ||

Plantar fascia stretching consists of the patient crossing the affected leg over the contralateral leg and using the fingers across to the base of the toes to apply pressure into toe extension until a stretch can be felt along the plantar fascia. Achilles tendon stretching can be performed in a standing position with the affected leg placed behind the contralateral leg with the toes pointed forward. The front knee was then bent, keeping the back knee straight and heel on the ground. The back knee could then be in a flexed position for more of a soleus stretch<ref name="DioGiovanni">DioGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME et al. Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhance outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2003;85-A:1270-1277</ref>. | |||

Mobilizations and manipulations have also been shown to decrease pain and relieve symptoms in some cases. Posterior talocrural joint mobs and subtalar joint distraction manipulation have been performed with the hypomobile talocrural joint. Patients in 6 different cases demonstrated complete pain relief and full return to activities with an average of 2-6 treatments per case<ref>Young B, Walker MJ, Strunce J et al.&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp; A combined treatment approach emphasizing impairment-based manual physical therapy for plantar heal pain: a case series.&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp; JOSPT. 2004;34:725-733.</ref>. | |||

Posterior-night splints maintain ankle dorsiflexion and toe extension, allowing for a constant stretch on the plantar fascia. Some evidence reports night splints to be beneficial but in a review by Cole et al he reported that there was limited evidence to support the use of night splints to treat patients with pain lasting longer than six months, and patients treated with custom made night splints improved more than prefabricated night splints<ref name="Cole">Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J. Plantar fasciitis: evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Dec 1;72(11):2237-42.</ref>. | |||

= | Six treatments of acetic acid iontophoresis combined with taping gave greater relief from stiffness symptoms than, and equivalent relief from pain symptoms to, treatment with dexamethasone/taping. For the best clinical results at four weeks, taping combined with acetic acid is the preferred treatment option compared with taping combined with dexamethasone or saline iontophoresis<ref name="Osborne">Osborne HR, Allison GT. Treatment of plantar fasciitis by LowDye taping and iontophoresis: short term results of a double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled clinical trial of dexamethasone and acetic acid. Br J Sports Med. 2006 Jun;40(6):545-9; discussion 549. Epub 2006 Feb 17.</ref>.<br> | ||

When used in conjunction with a stretching program, a prefabricated shoe insert is more likely to produce improvement in symptoms as part of the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis than a custom polypropylene orthotic device<ref name="Pfeffer">Pfeffer G, Bacchetti P, Deland J et al. Comparison of custom and prefabricated orthoses in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1999 Apr;20(4):214-21.</ref>. | |||

= | Foot orthoses produce small short-term benefits in function and may also produce small reductions in pain for people with plantar fasciitis, but they do not have long-term beneficial effects compared with a sham device whether they are custom made or prefabricated<ref name="Landorf">Landorf KB, Keenan AM, Herbert RD. Effectiveness of foot orthoses to treat plantar fasciitis: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jun 26;166(12):1305-10.</ref>. | ||

In a new study in 2008, a study was performed involving endoscopic plantar fasciotomy. It was concluding that a fasciotomy could be a reasonable option in the treatment of chronic heel pain that fails to respond to a trial of conservative treatment. Fifty-five patients had the procedure performed and 80% of those patients had a positive outcome. Research is still needed in this area <ref name="Urovitz">Urovitz EP, Birk-Urovitz A, Birk-Urovitz E. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy in the treatment of chronic heel pain. Can J Surg. 2008 Aug;51(4):281-3</ref><br> | |||

Recent searches were done toward the effects of short-term treatment with kinesiotaping for plantar fasciitis. For an entire week the tape was placed on the gastrocnemius and the plantar fascia. It was concluded that the additional treatment with continuous kinesiotaping for one week might alleviate the pain of plantar fasciitis better than a traditional physical therapy program only, but it’s a short-time effect. | |||

The [[Windlass test|windlass mechanism]] describes the manner by which the plantar fascia supports the foot during weight- bearing activities and provides information regarding the biomechanical stresses placed on the plantar fascia. | |||

To assess the efficacy of a taping construction as an intervention or as part of an intervention in patients with plantar fasciitis on pain and disability, controlled trials were searched for in CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Cochrane CENTRAL, and PEDro using a specific search strategy. The Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale was used to judge methodological quality. Clinical relevance was assessed with five specific questions. A best-evidence synthesis consisting of five levels of evidence was applied for qualitative analysis. <ref>Chien-Tsung Tsai et al., Effects of Short-Term Treatment with kinesiotaping for Plantar fasciitis, Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain, March 2010, Vol. 18, No. 1, Pages 71-80</ref><ref>Lori. A. Bolgla – Terry R. Malone, Plantar fasciitis and the Windlass mechanism, Journal of Athletic Training. 2004 (Jan- Mar); 39(1): 77-82</ref><ref>Alexander T. M. van de Water, Caroline M. Speksnijder, Efficacy of taping for the treatment of plantar fasciosis: a systematic review, Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 2010; 1: 41-51</ref><br> | |||

== Key Research == | == Key Research == | ||

| Line 214: | Line 149: | ||

== Resources <br> == | == Resources <br> == | ||

{| width="100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" | {| width="100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| {{#ev:youtube& | | {{#ev:youtube&amp;#124;Pe6UEck_hIY&amp;#124;300}} | ||

| {{#ev:youtube& | | {{#ev:youtube&amp;#124;kStuJAu0a20&amp;#124;300}} | ||

|} | |} | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

== Recent Related Research (from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ Pubmed]) == | == Recent Related Research (from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ Pubmed]) == | ||

| Line 254: | Line 187: | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project|Template:VUB]] [[Category:EIM_Residency_Project]] [[Category:Foot]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project|Template:VUB]] [[Category:EIM_Residency_Project]] [[Category:Foot]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] | ||

Revision as of 23:38, 7 March 2017

Original Editors

Top Contributors - Admin, Kris Porter, Rachael Lowe, Elien Lebuf, Bert Pluym, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Kim Jackson, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Jonathan Wong, Brooke Kennedy, Lucinda hampton, Scott Buxton, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Jeroen Van Cutsem, Thomas Janicky, Elke Lathouwers, Vidya Acharya, Kai A. Sigel, Aminat Abolade, Lisa Couck, Khloud Shreif, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Tony Lowe, Jarapla Srinivas Nayak, Keta Parikh, Stijn Van de Vondel, WikiSysop, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Rishika Babburu, Padraig O Beaglaoich, Jessica Galasso, Sehriban Ozmen, Shaimaa Eldib, Yahya Al-Razi, Claire Knott, Saud Alghamdi, David Csepe, Wanda van Niekerk and Jess Bell

Original Editor - Brooke Kennedy

Top Contributors - Admin, Kris Porter, Rachael Lowe, Elien Lebuf, Bert Pluym, Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Kim Jackson, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Jonathan Wong, Brooke Kennedy, Lucinda hampton, Scott Buxton, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Jeroen Van Cutsem, Thomas Janicky, Elke Lathouwers, Vidya Acharya, Kai A. Sigel, Aminat Abolade, Lisa Couck, Khloud Shreif, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Tony Lowe, Jarapla Srinivas Nayak, Keta Parikh, Stijn Van de Vondel, WikiSysop, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Rishika Babburu, Padraig O Beaglaoich, Jessica Galasso, Sehriban Ozmen, Shaimaa Eldib, Yahya Al-Razi, Claire Knott, Saud Alghamdi, David Csepe, Wanda van Niekerk and Jess Bell

Topic Expert - Kris Porter

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Plantar fasciitis may be referred to as plantar fasciosis, plantar heel pain, plantar fascial fibramatosis, among others. Because many cases diagnosed as “plantar fasciitis” are not inflammatory conditions, this condition may be best referred to as "plantar fasciosis." This is confirmed through histological analysis which demonstrates plantar fascia fibrosis, collagen cell death, vascular hyperplasia, random and disorganized collagen, and avascular zones.[1] There are many different sources of pain in the plantar heel besides the plantar fascia, and therefore the term "Plantar Heel Pain" serves best to include a broader perspective when discussing this and related pathology.

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The plantar fascia is comprised of white longitudinally organized fibrous connective tissue which originates on the periosteum of the medial calcaneal tubercle, where it is thinner but it extends into a thicker central portion. The thicker central portion of the plantar fascia then extends into five bands surrounding the flexor tendons as it passes all 5 metatarsal heads. Pain in the plantar fascia can be insertional and/or non-insertional and may involve the larger central band, but may also include the medial and lateral band of the plantar fasica. The plantar fascia is best referred to as fascia because of it's relatively variable fiber orientation as opposed to the more linear fiber orientation of aponeurosis. The plantar fascia blends with the paratenon of the Achilles tendon, the intrinsic foot musculature and even the skin and subcutaneous tissue.[2][3] The thick viscoelastic multilobular fat pad is responsible for absorbing up to 110% of body weight during walking and 250% during running and deforms most during barefoot walking vs. shod walking.[4]

During weight-bearing, the tibia loads the the foot “truss” and creates tension through the plantar fascia (see image_pending). The tension created in the plantar fascia adds critical stability to a loaded foot with minimal muscle activity. Evidence of the important stabilizing nature of the plantar fascia is evidence when following cases post surgical releas which may lead to midfoot arthritis, rupture of the secondary stabilizers of the arch (e.g spring ligament) , as well as other pathologies.[5][6][7]

Epidemiology & Etiology[edit | edit source]

The average plantar heel pain episode lasts longer than 6 months and it affects up to 10-15% of the population. However, approximately 90% of cases are treated successfully with conservative care.[8][9][10] Although this condition is seen in all ages, it is most commonly expereinced during middle age. Females present with plantar heel slightly more commonly than males and occurs more frequently in an athletic population such as running, accounting for up to 8-10% of all running related injuries.[11] In the US alone, there are estimates that this disorder generates up to 2 million patient visits per year, and account for 1% of all visits to orthopedic clinics. Plantar heel pain is the most common foot condition treated in physical therapy clinics and accounts for up to 40% of all patients being seen in podiatric clinics.[12]

There are many risk factors which contribute to plantar heel pain including but not limited too:

- Loss of ankle dorsiflexion (talocrural joint, deep or superficial posterior compartment)

- Pes cavus OR pes planus deformities

- Excessive foot pronation dynamically

- Impact/weight bearing activities such as prolonged standing, running, etc

- Improper shoe fit

- Elevated BMI > kg/m2

- Diabetes Mellitus (and/or other metabolic conditions)

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Heel pain with first steps in the morning or after long periods of non-weight bearing

- Tenderness to the anterior medial heel

- limited dorsiflexion and tight achilles tendon

- a limp may be present or may have a preference to toe walking

- pain is usually worse when barefoot on hard surfaces and with stair climbing

- many patients may have had a sudden increase in their activity level prior to the onset of symptoms

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Neurological - abductor digiti quinti nerve entrapment, lumbar spine disorders, problems with medial calcaneal branch of the posterior tibial nerve, tarsal tunnel syndrome

Soft tissue - [[Achilles_Tendonitis|achilles tendonitis}], fat pad atrophy, heel contusion, plantar fascia rupture, posterior tibial tendonitis, retrocalcaneal bursitis

Skeletal - Sever's disease, calcaneal stress fracture, infections, inflammatory arthropathies, subtalar arthritis

Miscellaneous - metabolic disorders, osteomalacia, Paget's disease, sickle cell disease, tumors (rare), vascular insufficiency,Rheumatoid arthritis

For further characteristics on each of these conditions, click on the Cole et al article below

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Plantar fasciitis is a clinical diagnosis. It is based on patient history and physical exam. Patients can have local point tenderness along the medial tuberosity of the os calcis, pain on the first steps or after training. Plantar facia pain is especially evident upon dorsiflexion of the patients pedal phalanges, which further stretches the plantar fascia. Therefore, any activity that would increase stretch of the plantar fascia, such as walking barefoot without any arch support, climbing stairs, or toe walking can worsen the pain. The clinical examination will take under consideration a patient's medical history, physical activity, foot pain symptoms and more. The doctor may decide to use Imaging studies like radiographs, diagnostic ultrasound and MRI.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The FAAM, or Foot and Ankle Ability Measure, is a good outcome measure to give to patients that are diagnosed with plantar fascitis.

A few studies have also used the Foot Function Index but only the the pain subscale. It is a validated measure, and the first 7 items of the pain subscale are used as the primary numeric outcome measure. Items are scored from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) depending on the mark on the visual analog scale. The sum of the 7 items is then expressed as a percentage of maximum possible score, ranging in an overall percentage.

Examination[edit | edit source]

The clinical examination will take under consideration a patient's medical history, physical activity, foot pain symptoms and more. The doctor may decide to use Imaging studies like radiographs, diagnostic ultrasound and MRI.

- Fabrikant et al could conclude that office-based ultrasound can help diagnose and confirm plantar fasciitis/fasciosis through the measurement of the plantar fascia thickness. Because of the advantages of ultrasound-that it is non-invasive with greater patient acceptance, cost effective and radiation-free-the imaging tool should be considered and implemented early in the diagnosis and treatment of plantar fasciitis/fasciosis. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title (level 3) - Sutera et al found that imaging the ankle/hind foot in the upright weight-bearing position with a dedicated MR scanner and a dedicated coil might enable the identification of partial tears of the plantar fascia, which could be overlooked in the supine position. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name cannot be a simple integer. Use a descriptive title (level 3) - Risk factors to look for by the examination of plantar fasciitis are:

- Reduced ankle dorsiflexion

- Obesity

- Work-related weight-bearing

- Reduced ankle dorsiflexion appears to be the most important risk factor.

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

When conservative measures fail, surgical plantar fasciotomy with or without heel spur removal may be employed. There is a method, through an open procedure, percutaneously or most common endoscopically, that releases the plantar fascia. This is an effective treatment, without the need for removal of a calcaneal spur, when present. There is a professional consensus, 70-90% of heel pain patients can be managed by non-operative measures. Surgery for plantar fasciitis should be considered only after all other forms of treatment have failed. With an endoscopic plantar fasciotomy, using the visual analog scale, the average post-operative pain was improved from 9.1 to 1.6. For the second group (ESWT), using the visual analog scale the average post-operative pain was improved from 9 to 2.1. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy gives better results than extra-corporeal shock wave therapy, but with liability of minor complications.[13] [14]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

The most common treatments include stretching of the gastroc/soleus/plantar fascia, orthotics, ultrasound, iontophoresis, night splints, joint mobilization/manipulation, and surgery.

Plantar fascia stretching consists of the patient crossing the affected leg over the contralateral leg and using the fingers across to the base of the toes to apply pressure into toe extension until a stretch can be felt along the plantar fascia. Achilles tendon stretching can be performed in a standing position with the affected leg placed behind the contralateral leg with the toes pointed forward. The front knee was then bent, keeping the back knee straight and heel on the ground. The back knee could then be in a flexed position for more of a soleus stretch[15].

Mobilizations and manipulations have also been shown to decrease pain and relieve symptoms in some cases. Posterior talocrural joint mobs and subtalar joint distraction manipulation have been performed with the hypomobile talocrural joint. Patients in 6 different cases demonstrated complete pain relief and full return to activities with an average of 2-6 treatments per case[16].

Posterior-night splints maintain ankle dorsiflexion and toe extension, allowing for a constant stretch on the plantar fascia. Some evidence reports night splints to be beneficial but in a review by Cole et al he reported that there was limited evidence to support the use of night splints to treat patients with pain lasting longer than six months, and patients treated with custom made night splints improved more than prefabricated night splints[17].

Six treatments of acetic acid iontophoresis combined with taping gave greater relief from stiffness symptoms than, and equivalent relief from pain symptoms to, treatment with dexamethasone/taping. For the best clinical results at four weeks, taping combined with acetic acid is the preferred treatment option compared with taping combined with dexamethasone or saline iontophoresis[18].

When used in conjunction with a stretching program, a prefabricated shoe insert is more likely to produce improvement in symptoms as part of the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis than a custom polypropylene orthotic device[19].

Foot orthoses produce small short-term benefits in function and may also produce small reductions in pain for people with plantar fasciitis, but they do not have long-term beneficial effects compared with a sham device whether they are custom made or prefabricated[20].

In a new study in 2008, a study was performed involving endoscopic plantar fasciotomy. It was concluding that a fasciotomy could be a reasonable option in the treatment of chronic heel pain that fails to respond to a trial of conservative treatment. Fifty-five patients had the procedure performed and 80% of those patients had a positive outcome. Research is still needed in this area [21]

Recent searches were done toward the effects of short-term treatment with kinesiotaping for plantar fasciitis. For an entire week the tape was placed on the gastrocnemius and the plantar fascia. It was concluded that the additional treatment with continuous kinesiotaping for one week might alleviate the pain of plantar fasciitis better than a traditional physical therapy program only, but it’s a short-time effect.

The windlass mechanism describes the manner by which the plantar fascia supports the foot during weight- bearing activities and provides information regarding the biomechanical stresses placed on the plantar fascia.

To assess the efficacy of a taping construction as an intervention or as part of an intervention in patients with plantar fasciitis on pain and disability, controlled trials were searched for in CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Cochrane CENTRAL, and PEDro using a specific search strategy. The Physiotherapy Evidence Database scale was used to judge methodological quality. Clinical relevance was assessed with five specific questions. A best-evidence synthesis consisting of five levels of evidence was applied for qualitative analysis. [22][23][24]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME et al. Tissue-specific plantar fascia stretching exercises enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2003;85-A:1270-1277.

According to a prospective, randomized controlled trial by DiGiovanni, stretching can be an appropriate treatment for plantar fascitis as long as it is specific stretching. He compared patients who received either a plantar-fascia tissue-stretching program compared to patients who received an achilles tendon stretching program. The plantar fascia stretching consisted of one stretch to be performed before taking their first step in the morning. The patient crossed the affected leg over the contralateral leg and used the fingers across to the base of the toes to apply pressure into toe extension until a stretch was felt along the plantar fascia. In the achilles-tendon stretching group, the stretch was performed in a standing position and to be performed immediately after getting out of bed in the morning. A shoe insert was placed under the affected foot, and the affected leg was placed behind the contralateral leg with the toes pointed forward. The front knee was then bent, keeping the back knee straight and heel on the ground. Both stretches for both groups were to be held 10 secondes for 10 repetitions, 3 times a day. The results indicated that both groups improved but the planta fascia specific stretching was superior. The protocol was linked to the use of dorsiflexion night splints that incorporate toe dorsiflexion, but reported the stretching program had advantages over night splints.

Pfeffer G, Bacchetti P, Deland J et al. Comparison of custom and prefabricated orthoses in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1999 Apr;20(4):214-21.

Abstract

Fifteen centers for orthopaedic treatment of the foot and ankle participated in a prospective randomized trial to compare several nonoperative treatments for proximal plantar fasciitis (heel pain syndrome). Included were 236 patients (160 women and 76 men) who were 16 years of age or older. Most reported duration of symptoms of 6 months or less. Patients with systemic disease, significant musculoskeletal complaints, sciatica, or local nerve entrapment were excluded. We randomized patients prospectively into five different treatment groups. All groups performed Achilles tendon- and plantar fascia-stretching in a similar manner. One group was treated with stretching only. The other four groups stretched and used one of four different shoe inserts, including a silicone heel pad, a felt pad, a rubber heel cup, or a custom-made polypropylene orthotic device. Patients were reevaluated after 8 weeks of treatment. The percentages improved in each group were: (1) silicone insert, 95%; (2) rubber insert, 88%; (3) felt insert, 81%; (4)stretching only, 72%; and (5) custom orthosis, 68%. Combining all the patients who used a prefabricated insert, we found that their improvement rates were higher than those assigned to stretching only (P = 0.022) and those who stretched and used a custom orthosis (P = 0.0074). We conclude that, when used in conjunction with a stretching program, a prefabricated shoe insert is more likely to produce improvement in symptoms as part of the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis than a custom polypropylene orthotic device.

Osborne HR, Allison GT. Treatment of plantar fasciitis by LowDye taping and iontophoresis: short term results of a double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled clinical trial of dexamethasone and acetic acid. Br J Sports Med. 2006 Jun;40(6):545-9; discussion 549. Epub 2006 Feb 17.

OBJECTIVES: To determine if, in the short term, acetic acid and dexamethasone iontophoresis combined with LowDye (low-Dye) taping are effective in treating the symptoms of plantar fasciitis. METHODS: A double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled trial of 31 patients with medial calcaneal origin plantar fasciitis recruited from three sports medicine clinics. All subjects received six treatments of iontophoresis to the site of maximum tenderness on the plantar aspect of the foot over a period of two weeks, continuous LowDye taping during this time, and instructions on stretching exercises for the gastrocnemius/soleus. They received 0.4% dexamethasone, placebo (0.9% NaCl), or 5% acetic acid. Stiffness and pain were recorded at the initial session, the end of six treatments, and the follow up at four weeks. RESULTS: Data for 42 feet from 31 subjects were used in the study. After the treatment phase, all groups showed significant improvements in morning pain, average pain, and morning stiffness. However for morning pain, the acetic acid/taping group showed a significantly greater improvement than the dexamethasone/taping intervention. At the follow up, the treatment effect of acetic acid/taping and dexamethasone/taping remained significant for symptoms of pain. In contrast, only acetic acid maintained treatment effect for stiffness symptoms compared with placebo (p = 0.031) and dexamethasone. CONCLUSIONS: Six treatments of acetic acid iontophoresis combined with taping gave greater relief from stiffness symptoms than, and equivalent relief from pain symptoms to, treatment with dexamethasone/taping. For the best clinical results at four weeks, taping combined with acetic acid is the preferred treatment option compared with taping combined with dexamethasone or saline iontophoresis.

Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J. Plantar fasciitis: evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Dec 1;72(11):2237-42.

Plantar fasciitis causes heel pain in active as well as sedentary adults of all ages. The condition is more likely to occur in persons who are obese or in those who are on their feet most of the day. A diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is based on the patient's history and physical findings. The accuracy of radiologic studies in diagnosing plantar heel pain is unknown. Most interventions used to manage plantar fasciitis have not been studied adequately; however, shoe inserts, stretching exercises, steroid injection, and custom-made night splints may be beneficial. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy may effectively treat runners with chronic heel pain but is ineffective in other patients. Limited evidence suggests that casting or surgery may be beneficial when conservative measures fail.

Landorf KB, Keenan AM, Herbert RD. Effectiveness of foot orthoses to treat plantar fasciitis: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jun 26;166(12):1305-10.

BACKGROUND: Plantar fasciitis is one of the most common foot complaints. It is often treated with foot orthoses; however, studies of the effects of orthoses are generally of poor quality, and to our knowledge, no trials have investigated long-term effectiveness. The aim of this trial was to evaluate the short- and long-term effectiveness of foot orthoses in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. METHODS: A pragmatic, participant-blinded, randomized trial was conducted from April 1999 to July 2001. The duration of follow-up for each participant was 12 months. One hundred and thirty-five participants with plantar fasciitis from the local community were recruited to a university-based clinic and were randomly allocated to receive a sham orthosis (soft, thin foam), a prefabricated orthosis (firm foam), or a customized orthosis (semirigid plastic). RESULTS: After 3 months of treatment, estimates of effects on pain and function favored the prefabricated and customized orthoses over the sham orthoses, although only the effects on function were statistically significant. Compared with sham orthoses, the mean pain score (scale, 0-100) was 8.7 points better for the prefabricated orthoses (95% confidence interval, -0.1 to 17.6; P = .05) and 7.4 points better for the customized orthoses (95% confidence interval, -1.4 to 16.2; P = .10). Compared with sham orthoses, the mean function score (scale, 0-100) was 8.4 points better for the prefabricated orthoses (95% confidence interval, 1.0-15.8; P = .03) and 7.5 points better for the customized orthoses (95% confidence interval, 0.3-14.7; P = .04). There were no significant effects on primary outcomes at the 12-month review. CONCLUSIONS: Foot orthoses produce small short-term benefits in function and may also produce small reductions in pain for people with plantar fasciitis, but they do not have long-term beneficial effects compared with a sham device. The customized and prefabricated orthoses used in this trial have similar effectiveness in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

Urovitz EP, Birk-Urovitz A, Birk-Urovitz E. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy in the treatment of chronic heel pain. Can J Surg. 2008 Aug;51(4):281-3

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate endoscopic plantar fasciotomy for the treatment of recalcitrant heel pain. METHOD: We undertook a retrospective study of the use of endoscopic plantar fasciotomy in the treatment of chronic heel pain that was unresponsive to conservative treatment. Over a 10-year period, we reviewed the charts of 55 patients with a minimum 12-month history of heel pain that failed to respond to standard nonoperative methods and had undergone the procedure described. All patients were clinically reviewed and completed a questionnaire based on the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score for ankle and hindfoot. RESULTS: The mean follow-up was 18 months. The mean preoperative AOFAS score was 66.5; the mean postoperative AOFAS score was 88.2. The mean preoperative pain score was 18.6; the mean postoperative pain score was 31.1. Complications were minimal (2 superficial wound infections). Overall, results were favourable in over 80% of patients. CONCLUSION: We conclude that endoscopic plantar fasciotomy is a reasonable option in the treatment of chronic heel pain that fails to respond to a trial of conservative treatment.

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Young B, Walker MJ, Strunce J et al. A combined treatment approach emphasizing impairment-based manual physical therapy for plantar heal pain: a case series. JOSPT. 2004;34:725-733.

In a case series by B Young et al, they described an impairment-based physcial therapy treatment approach for 4 patients with plantar heel pain. All patients received manual therapy, consisting of posterior talocrural joint mobs and subtalar joint distraction manipulation, in combination with calf-stretching, plantar fascia stretching, and self-anterior-posterior ankle mobilization as a home program. They demonstrated complete pain relief and full return to activities with an average of 2-6 treatments per case.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

EmbedVideo is missing a required parameter.

|

EmbedVideo is missing a required parameter.

|

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1houoX_LGC305ro2l-cEh_uDPlVE-LuIbL2pcsEP2W6Il42kL|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

- Labovitz J et al; The Role of Hamstring Tightness in Plantar Fasciitis; Foot Ankle Spec. 2011 Mar 2. [Epub ahead of print]

Read 4 Credit[edit | edit source]

|

Would you like to earn certification to prove your knowledge on this topic? All you need to do is pass the quiz relating to this page in the Physiopedia member area.

|

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Lemont H, Ammirati KM, Usen N. Plantar fasciitis: a degenerative process (fasciosis) without inflammation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93(3):234–7.

- ↑ Carlson RE, Fleming LL, Hutton WC. The biomechanical relationship between the tendoachilles, plantar fascia and metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion angle. Foot ankle Int / Am Orthop Foot Ankle Soc [and] Swiss Foot Ankle Soc. 2000;21(1):18–25.

- ↑ Stecco C, Corradin M, Macchi V, et al. Plantar fascia anatomy and its relationship with Achilles tendon and paratenon. J Anat. 2013;223(August):1–12. doi:10.1111/joa.12111.

- ↑ Gefen A, Megido-Ravid M, Itzchak Y. In vivo biomechanical behavior of the human heel pad during the stance phase of gait. J Biomech. 2001;34:1661–1665. doi:10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00143-9

- ↑ Tweed JL, Barnes MR, Allen MJ, Campbell J a. Biomechanical consequences of total plantar fasciotomy: a review of the literature. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009;99(5):422–30.

- ↑ Cheung JT-M, An K-N, Zhang M. Consequences of partial and total plantar fascia release: a finite element study. Foot ankle Int / Am Orthop Foot Ankle Soc [and] Swiss Foot Ankle Soc. 2006;27(2):125–32. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16487466.

- ↑ Crary JL, Hollis JM, Manoli A. The effect of plantar fascia release on strain in the spring and long plantar ligaments. Foot ankle Int / Am Orthop Foot Ankle Soc [and] Swiss Foot Ankle Soc. 2003;24(3):245–50

- ↑ McPoil TG, Martin RL, Cornwall MW, Wukich DK, Irrgang JJ, Godges JJ. Heel pain--plantar fasciitis: clinical practice guildelines linked to the international classification of function, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(4):A1–A18. doi:10.2519/jospt.2008.0302.

- ↑ Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for Plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(5):872–7

- ↑ Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline-revision 2010. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(3 Suppl):S1–19. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2010.01.001

- ↑ Lopes AD, Hespanhol Júnior LC, Yeung SS, Costa LOP. What are the main running-related musculoskeletal injuries? A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2012;42(10):891–905. doi:10.2165/11631170-000000000-00000.

- ↑ 2002 Podiatric Practice Survey. Statistical results. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93(1):67–86. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12533562.

- ↑ JG Furey, Plantar fasciitis. The painfull heel syndrome, The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 57:672-673 (2010)

- ↑ Ahmed Mohamed Ahmed Othman – Ehab Mohamed Ragab, Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy versus extracorporeal shock wave therapy for treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis, Orthopaedic surgery (2009)

- ↑ DioGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME et al. Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhance outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2003;85-A:1270-1277

- ↑ Young B, Walker MJ, Strunce J et al.&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp; A combined treatment approach emphasizing impairment-based manual physical therapy for plantar heal pain: a case series.&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp; JOSPT. 2004;34:725-733.

- ↑ Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J. Plantar fasciitis: evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Dec 1;72(11):2237-42.

- ↑ Osborne HR, Allison GT. Treatment of plantar fasciitis by LowDye taping and iontophoresis: short term results of a double blinded, randomised, placebo controlled clinical trial of dexamethasone and acetic acid. Br J Sports Med. 2006 Jun;40(6):545-9; discussion 549. Epub 2006 Feb 17.

- ↑ Pfeffer G, Bacchetti P, Deland J et al. Comparison of custom and prefabricated orthoses in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1999 Apr;20(4):214-21.

- ↑ Landorf KB, Keenan AM, Herbert RD. Effectiveness of foot orthoses to treat plantar fasciitis: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jun 26;166(12):1305-10.

- ↑ Urovitz EP, Birk-Urovitz A, Birk-Urovitz E. Endoscopic plantar fasciotomy in the treatment of chronic heel pain. Can J Surg. 2008 Aug;51(4):281-3

- ↑ Chien-Tsung Tsai et al., Effects of Short-Term Treatment with kinesiotaping for Plantar fasciitis, Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain, March 2010, Vol. 18, No. 1, Pages 71-80

- ↑ Lori. A. Bolgla – Terry R. Malone, Plantar fasciitis and the Windlass mechanism, Journal of Athletic Training. 2004 (Jan- Mar); 39(1): 77-82

- ↑ Alexander T. M. van de Water, Caroline M. Speksnijder, Efficacy of taping for the treatment of plantar fasciosis: a systematic review, Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 2010; 1: 41-51