Physical Activity in Cancer: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| {{#ev:youtube|1mo80kTZgW4|405}} | | {{#ev:youtube|1mo80kTZgW4|405}} | ||

|{{#ev:youtube|t7QDJOXeux4|405}} | |||

|} | |} | ||

== Definitions == | == Definitions == | ||

Revision as of 21:22, 8 August 2018

Original Editor - Samara Paull

Top Contributors - Vidya Acharya, Wendy Walker, Adam Vallely Farrell, Kapil Narale, Tony Lowe, Kim Jackson, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Khloud Shreif, George Prudden, Rucha Gadgil, Nicole Hills, Lucinda hampton, Giulia Neculaes, Admin, Michelle Lee and Tarina van der Stockt

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Cancer is a condition where cells in a specific part of the body grow and reproduce uncontrollably. The cancerous cells can invade and destroy surrounding healthy tissue, including organs. There are more than 200 different types of cancer, each with its own methods of diagnosis and treatment. For more detailed information on the pathophysiology and management of several of the different forms of cancer take a look at the Oncology Physiopedia page.

Decrease in physical fitness has been reported in both patients and survivors of childhood and adult cancers. This decline in physical activity is secondary to the side effects of both the disease and its treatment[1]. Cancer survivors have an increased risk for negative health and psychosocial effects following treatment. Beyond people with cancer, insufficient physical activity is the leading risk factors of death worldwide.

By addressing physical activity and stress reduction techniques patients can control some of these modifiable risk factors[2]. Furthermore, such adverse effects are aggravated by physical inactivity (such as reduced bone mineral density, loss of muscle mass, increased BMI and impaired motor performance) therefore more emphasis is being placed on integrating exercise and activity both during and after treatment[3].

With the increasing number of people diagnosed with cancer and surviving it, quality of life outcomes are increasing in importance with numerous studies supporting physical activity and its positive impact. In one systematic review, exercise and physical activity had a clinically relevant positive impact on health related quality of life both during and after medical intervention in people with cancer[4].

Definitions[edit | edit source]

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that result in energy expenditure.It includes all forms of activity, such as everyday walking or cycling to get from A to B, active play, work-related activity, active recreation (such as working out in a gym), dancing, gardening or playing active games, as well as organized and competitive sport[1]. Exercise is a subset of physical activity that is planned, structured, repeated and has a final or an intermediate objective to the improvement or maintenance of physical fitness[2]

Besides having significant health benefits, PA is also preventative in many diseases including cardiovascular disease and diabetes. General recommendations for daily physical activity are based on age and can be found at this link[5]: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/

Cancer[edit | edit source]

Cancer is a related group of diseases in which cell’s in the body begin to grow and divide uncontrollably. It can spread to other areas of the body. The National Cancer Institute states there are over 100 types of cancer based on its location in the body and can be found in both children and adults[6].

In 2012, an estimated 14.1 million new cases of cancer occurred worldwide. More than 4 in ten cancers occurring worldwide are in countries at a low or medium level of Human Development Index (HDI). The four most common cancers occurring worldwide are lung, female breast, bowel and prostate cancer. These four account for around 4 in 10 of all cancers diagnosed worldwide. [7]

Cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in Ireland with 7500 dying annually, roughly 1 in every 4 people. Cancer has a 5-year survival goal and if it is to return, it will usually occur within 5 years. Although cancer incidence appears to be falling, the actual number of people developing cancer is expected to increase because our population is ageing. The Irish Cancer society report that 20,000 Irish people develop cancer and 7,500 die yearly[8]. Ireland has the 4th highest breast cancer mortality rates worldwide (approx.26/100,000). [8]

Benefits of PA for Individuals with Cancer[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is not only beneficial for patients following activity cancer treatment but also during to help with the negative side effects secondary to the treatment itself. It has a positive impact on both physical and psychosocial factors such as fatigue, low mood and stress, overall deconditioning and loss of independence[9]. Specific programs also provide benefits following treatments including post surgical tumor removal and lymphoedema management[9]. Other benefits of exercise including helping to maintain a healthy body weight, anti-thrombotic effect decreasing platelet adhesiveness, improved endothelial function, increased HDL cholesterol, decreased risk of NIDDM and reduced risk of other diseases e.g. heart disease, diabetes, osteoporosis and hypertension.

PA as a preventative method for cancer[edit | edit source]

Physical activity has also been linked to the prevention of certain cancers including Breast, Colon, Endometrial and Prostate, as well as some cancers associated with increased weight gain[9]. It also prevents the re-occurrence of the same cancers[10].

Cancer prevention by modifying environmental and lifestyle factors is the most viable long term strategy. Physical activity has been shown to reduce the risk of colon, breast and endometrial cancers by 25-50% in physically active individuals. There is emerging evidence for prostate, ovarian, lung and GI cancers. For cancer prevention 4-5 hours of moderate exercise per week is required. This reduced risk is likely due to insulin resistance, endogenous sex and metabolic hormone levels, inflammation, growth factors and enhanced immune function.

Physical activity decreases obesity and central adiposity which are established risk factors for colon, postmenopausal, endometrial, kidney and oesophageal cancers. Obesity mediates the carcinogenic effect via a shift in sex and metabolic hormone balance in the body, influencing insulin resistance, inflammatory pathways, energy related signalling and growth factors.

Please see: http://fyss.se/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/19.-Cancer.pdf for more information on the biological mechanisms of physical activity on cancer.

Role of the Physiotherapist[edit | edit source]

There is a growing body of evidence that supports the role of the physiotherapist in the care of patients with cancer. This ranges from; Prevention – exercise to prevent cancer (especially colon and post-menopausal breast cancer). Obesity is strongly linked to the development of a number of cancers (adipose tissue is a tumour friendly environment). In the acute setting the physiotherapist can be involved in the pre-op assessment and enhanced recovery after surgery. Advice and education on lymphedema prevention, wound, stretching and massage, return to work and physical activity.

Exercise prescription is a large part of rehabilitation post op. The physiotherapist has a role in developing a tailored and individualised rehabilitation programme and specific exercise instruction post breast surgery. The Breast Cancer Physiopedia page has detailed information of physiotherapy management in the breast cancer patient. They can also encourage exercise during chemo/radiotherapy.

Physiotherapists play an essential role in the interdisciplinary and holistic approach to palliative care by providing increased quality of life, function, and overall experience through physical and functional dimensions of care.

PA in Pediatric Cancer[edit | edit source]

There are few systematic reviews that exist summarizing the positive effects of physical activity in pediatric oncology in comparison to adult studies. However, Baumann and Bloch (2013)[11] determined that exercise interventions are not only feasible and safe, but also no adverse side effects were reported. There was a positive effect on fatigue, strength and quality of life[11].

Beyond physical benefits there was increased self report of improvements in comfort and resilience to the disease following a relatively short term supervised exercise training programs[12]. Li et al. (2013) reported an adventure based health education program led to statistically significant improvements in their participants’ self-efficacy[13]. Physical activity has also been shown to safe and effective despite the aggressiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy during treatment for solid tumors in pediatric cancer patients[14]. More studies are needed regarding cognitive abilities, growth and re-integration into peer groups, school and sports.

Guidelines for PA in Cancer[edit | edit source]

there are a large number of studies which show that physical activity is safe and appropriate for prior to, during and after active treatment[1][3][4][5][11][12][15]. With any exercise program it is important for an individual to consult with their doctor and medical team prior to beginning any intervention.

The American Cancer Society (ACS), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) have all made physical activity recommendations for cancer survivors post-diagnosis,Which also factor for improvements in managing some of the common side effects such as fatigue and pain. The most agreed-upon recommendations are that all patients should avoid inactivity and return to normal daily activities as soon as possible after diagnosis. That they engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic exercise per week, and that they include resistance-training exercises at least two days per week.[16] [17] To improve flexibility, adults should also stretch the major muscle groups and tendons on days they participate in other types of activity; older adults will also benefit from balance exercises.[18]

Barriers to PA in Cancer[edit | edit source]

Exercise is safe both during and after most types of cancer treatment, including intensive life-threatening treatments such as bone-marrow transplants. Despite the proven benefits of exercise, even while receiving treatments, research shows that the many cancer patients report significant decreases in their physical activity levels after their cancer diagnosis.[19] Patients have identified both psychological and physical barriers as factors in their decrease in activity.

The Memorial sloan Kettering Cancer study recruited 622 cancer patients and identified psychological barriers including difficulty getting motivated (67% of subjects) and trouble remaining disciplined (65%). Physical barriers, including fatigue (78%) and pain (71%) associated with cancer treatments, as factors contributing to this decrease in activity. [20]

Further proposed benefits may include;

- Being immuno-compromised (secondary to low white cell count) leads to a high risk of infection. Patients need to be aware of the cleanliness of their environment. For example very busy public gyms can lead to infection, and hand washing must always be a priority.

- Having low platelet and haemoglobin levels (Anemia) leave patients fatigued and at higher risk for internal bleeding. Contact and high impact sports are not recommended when blood counts are low. Make sure to check with a physician before engaging in activity

- Over 90% of patients undergoing cancer treatment experience fatigue and pain related symptoms. It is important to encourage daily low intensity physical activity to prevent deconditioning and further increase fatigue.

- Fear and feeling overwhelmed sometimes makes it harder to prioritise physical activity amongst their other chemotherapy, radiation and medication schedules.

Contra-indications to PA in Cancer[edit | edit source]

Bertorello et al. (2011) studied physical activity and late effects on long term Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia survivors and determined not only is exercise NOT contra-indicated but should be promoted as much as possible[21] and No exercise related risks were encountered in either adults or children with hematological cancer[22]. However, if a child or adult has an implanted device for chemotherapy, such as a Broviac, or a feeding tube or catheter, swimming may be contra-indicated due to the high risk of infection.

Precautions[edit | edit source]

Also, with certain cancers extra precautions need to be considered[23][24].

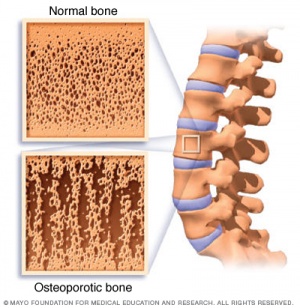

- Bone cancer or osteosarcoma: patients need to understand their weight bearing status which can change based on the integrity of the bone. They are at higher risk for fracture and should consider lower impact activities such as swimming or yoga. This is also true of patients with osteoporosis.

- Chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy: Sensation changes or loss in the hands and/or feet may make certain activities more difficult or increase likelihood of injuries and falls. Stationary biking is a good alternative to running because of its low impact and allows longer duration of activity prior to fatigue.

- Following breast cancer resections, patients should begin with gentle range of motion activities and should avoid aggressive upper extremity strengthening programs. A physical therapist can progress their exercise program to help prevent lymphodema and further injury to the area.

- Patients with compromised/reduced immune function (this includes those with low white blood cell count as well as those on immuno-suppressing medication) should avoid exercising in public gyms or swimming pools, due to risk of infection.

Promotion of PA[edit | edit source]

Therapeutic Yoga[edit | edit source]

Yoga THRIVE is a therapeutic yoga program for cancer survivors. It is a research based, modified program to help with physical manifestations of cancer treatment like joint stiffness and pain and also emotional symptoms like stress and fatigue[25].

One study found that gross motor function improved in children participating in therapeutic yoga[26]. It is important to acknowledge that yoga has not been proven to cure or prevent cancer; however it can have positive benefits during and after treatment. More studies are needed for yoga as a complementary therapy for cancer patients[27].

Exercise Manuals[edit | edit source]

The Pediatric Oncology Exercise Manual (or POEM) is an evidence based tool for both parents and health professionals aimed at increasing physical activity for children with cancer.

Stride to Survive is another exercise guide aimed towards young adults who have completed treatment and want to begin a safe exercise program and increase their physical activity.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- The Motivate2Move website, created by Wales Deanery, has a very useful section on Physical Activity effects in Cancer

- The University of Calgary has a series of relevant infographics and a comprehensive document on PA in Pediatric Cancer, POEM

- Cancer Research UK has Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Patients

- The American Cancer Society has comprehensive information on their website about Physical Activity and the Cancer Patient

- Cancer Care Ontario has a document with detailed information about Exercise for People with Cancer

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Braam KI, van der Torre P, Takken T, Veening MA, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Kaspers GJL. Physical exercise training interventions for children and young adults during and after treatment for childhood cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 Mar 31;3:008796

- ↑ Rabin C, Pinto B, Fava J. Randomized Trial of a Physical Activity and Meditation Intervention for Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of Adolescent & Young Adult Oncology 2016 Mar;5(1):41-47

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 San Juan AF, Wolin K, Lucia A. Physical activity and pediatric cancer survivorship. Recent Results in Cancer Research 2011;186:319-347

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gerritsen JKW, Vincent AJPE. Exercise improves quality of life in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 2016 Jul;50(13):796-803

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 WHO. Physical Activity Fact sheet [Internet]. 2017 [cited 26/05/2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/

- ↑ National Cancer Institute. What is cancer? 2015 [cited 27/05/2017]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer

- ↑ http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/worldwide-cancer#heading-Zero

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 https://www.cancer.ie/about-us/media-centre/cancer-statistics#sthash.NaGuepDS.dpbs

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 American Cancer Society. ACS Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention. Benefits of Physical Activity. 2017 [cited 26/05/2017]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/healthy/eat-healthy-get-active/acs-guidelines-nutrition-physical-activity-cancer-prevention/guidelines.html

- ↑ World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutri- tion, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer. A global perspective. Washington (DC): American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR); 2007

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Baumann FT, Bloch W, Beulertz J. Clinical exercise interventions in pediatric oncology: a systematic review. Pediatr Res 2013 Oct;74(4):366-374

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 San Juan AF, Chamorro-Viña C, Moral S, Fernández del Valle M, Madero L, Ramírez M, et al. Benefits of intrahospital exercise training after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Int J Sports Med 2008 05;29(5):439-446

- ↑ Li HCW, Chung OKJ, Ho KY, Chiu SY, Lopez V. Effectiveness of an integrated adventure-based training and health education program in promoting regular physical activity among childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2013 Nov;22(11):2601-2610

- ↑ Fiuza-Luces C, Padilla Jr, Soares-Miranda L, Santana-Sosa E, Quiroga JV, Santos-Lozano A, et al. Exercise Intervention in Pediatric Patients with Solid Tumors: The Physical Activity in Pediatric Cancer Trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017 02;49(2):223-230

- ↑ Cancer Care Ontario. Guideline 19-5: A Quality Initiative of the program in Evidence-Based Care, Cancer Care Ontario. Exericse for People with Cancer. 2015 [cited 26/05/2017]

- ↑ Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, et al. “Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: an American Society of Clinical oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation.” J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 1840-1850.

- ↑ Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. “American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline.” J Clin Oncol. 2016;34: 611-635.

- ↑ Wolin KY, Schwartz AL, Matthews CE, Courneya KS, Schmitz KH. Implementing the exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. J Support Oncol. 2012;10: 171-177.

- ↑ McCabe, M. S., Bhatia, S., Oeffinger, K. C., Reaman, G. H., Tyne, C., Wollins, D. S., & Hudson, M. M. (2013). American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(5), 631.

- ↑ https://www.mskcc.org/clinical-updates/overcoming-barriers-maintaining-physical-activity-during-cancer-care

- ↑ Bertorello N, Manicone R, Galletto C, Barisone E, Fagioli F. Physical activity and late effects in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia long-term survivors. Pediatric Hematology & Oncology 2011 Aug;28(5):354-363

- ↑ Wolin KY, Ruiz JR, Tuchman H, Lucia A. Exercise in adult and pediatric hematological cancer survivors: an intervention review. Leukemia 2010 Jun;24(6):1113-1120

- ↑ Wolin KY, Ruiz JR, Tuchman H, Lucia A. Exercise in adult and pediatric hematological cancer survivors: an intervention review. Leukemia 2010 Jun;24(6):1113-1120

- ↑ American Cancer Society. Physical Activity for the Cancer Patient. Precautions for cancer survivors who want to exercise. 2017 [cited 26/05/2017]

- ↑ 24. Tom Baker Cancer Centre. Integrative Oncology Program. Yoga THRIVE. 2017 [cited 01/06/2017]

- ↑ Geyer R, Lyons A, Amazeen L, Alishio L, Cooks L. Feasibility study: the effect of therapeutic yoga on quality of life in children hospitalized with cancer. Pediatric Physical Therapy 2011 Winter;23(4):375-379

- ↑ Smith, K.B. & Pukall, C.F. An evidence-based review of yoga as a complementary intervention for patients with cancer. National Institute for Health Resources 2010 March; Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): 1-3