Pelvic Fractures

Original Editors - Rachael Lowe

Top Contributors - Descheemaeker Kari, Julie Stainier, Lynn Wright, Jentel Van De Gucht, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Lucinda hampton, 127.0.0.1, Kim Jackson, Rosie Swift, Scott Buxton, Aminat Abolade, Siobhán Cullen, Karen Wilson, Vidya Acharya, Claire Knott and Lauren Lopez

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

We searched for information in different scientific medical databases like PubMed, Pedro and Web of Science. Also, we went to a library and lend some books.

We started our search with the following key words: pelvis, fractures, pelvic fracture, physiotherapy, rehabilitation, surgery, … We searched these words by using Mesh terms. We specified our search by looking for recent articles (publication date last five years: 2011-2016).

Definition/description[edit | edit source]

A pelvic fracture is a disruption of the bony structures of the Pelvis. An anatomic ring is formed by the fused bones of the ilium, ischium and pubis attached to the sacrum. A pelvic fracture can occur by low-energy mechanism or by high-energy impact. They can range in severity from relatively benign injuries to life-threatening, unstable fractures.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

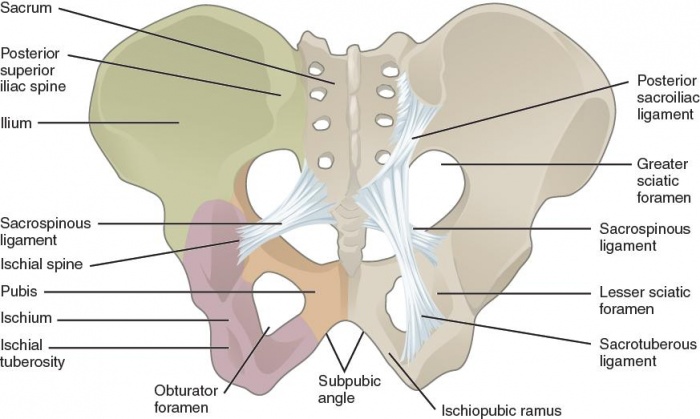

The bony pelvis is the entire structure formed by the two hip bones, the sacrum, and the coccyx, which is attached inferiorly to the sacrum. The paired hip bones are the large, curved bones that form the lateral and anterior aspects of the pelvis. Each adult hip bone is formed by three separate bones that fuse together during the late teenage years. These bony components are the ilium, ischium and pubis. [1](level of evidence: 5)

The stability of the pelvis relies on the integrity of the posterior weight-bearing sacroiliac complex and the transfer of weight bearing forces from the spine to the lower extremities. The SI joint (between sacrum and ilium) transmits forces from the upper limbs and spine to the hip joints and lower limbs and vice versa. This joint also acts as a shock absorber. Several muscles influence the movement and the stability of the SI joint either through attachment to the sacrum or the ilium, or ligamentous attachment to the strong anterior and posterior SI-joint ligaments. ⅔ of the joint includes the posterior superior ligamentous section and ⅓ of the joint includes the anterior inferior synovial component. [2] [3](level of evidence: 2B, 4)

The pelvis contains sliding, tilting and rotation movement components.

Major nerves, blood vessels, and portions of the bowel, bladder, and reproductive organs all pass through the pelvic ring. The pelvis protects these important structures from injury. It also serves as an anchor for the muscles of the hip, thigh and abdomen.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Pelvic fractures occur after both low-energy and high-energy events. The appearance of pelvic fractures is the greatest in people aged between 15 and 28. In persons, younger than 35, pelvic fractures occur more in males than in females. In persons, older than 35, pelvic fractures are more likely to happen to females than males[4]. In younger people, pelvic fractures occur mostly as a result of high-energy mechanisms. In older people, they occur from minimal trauma, such as a low fall. Elderly people with osteoporosis have a higher risk factor.

Low-energy fractures are usually stable fractures of the pelvic ring. High-energy pelvic fractures arise commonly after motor vehicle crashes, motorcycle crashes, motor vehicles striking pedestrians and falls. Those high-energy pelvic fractures are one of the major injuries that lead to death. The presence of coma, shock, and head and chest injuries are predictors of death. [5] (level of evidence: 2B)

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

A pelvic fracture should always be considered when history of a significant trauma is present. Pelvic fractures may be recognized by: tenderness, pain, bruising, swelling and crepitus of the pubis, iliac bones, hips and sacrum. Other presenting factors are: haematuria, rectal bleeding, haematoma and neurological and vascular abnormalities in the legs. Physical findings could include abnormal position of the lower limbs and pelvic deformity or pelvic instability. With avulsion injuries, there is often pain associated with contraction of the involved muscles.[6]

There must be a differentiation between high impact unstable fractures and low impact stable pelvic fractures. This can be done by determination of the circumstances of the trauma. Patients with unstable fractures are usually unable to stand, in contrast to patients with stable fractures who can often walk unaided.

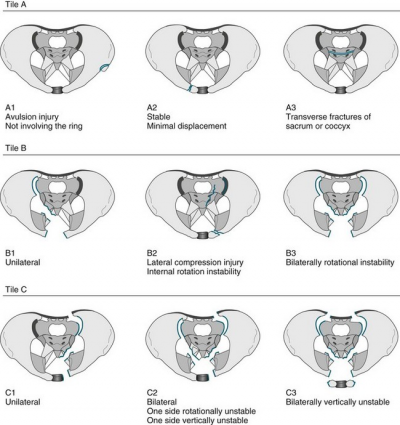

Pelvic fractures can be classified by several classification systems. The two most commonly used systems are Tiles classification and the Young-Burgess Classification.

Classification of pelvic fractures by Tile is based on the integrity of the posterior sacroiliac complex. [1] [2] (level of evidence: 5, 2B)

- Type A: rotationally and vertically stable, the sacroiliac complex is intact. Type A fractures are mostly managed non-operatively.

o A1: avulsion fractures

o A2: stable iliac wing fractures or minimally displaced pelvic ring fractures

o A3: transverse sacral or coccyx fractures - Type B: rotationally unstable and vertically stable, caused by external or internal rotational forces, results in partial disruption of the posterior sacroiliac complex.

o B1: open-book injuries

o B2: lateral compression injuries

o B3: bilateral rotational instability - Type C: rotationally unstable and vertically unstable, complete disruption of the posterior sacroiliac complex. These unstable fractures are mostly caused by high-energy trauma like falls from height, motor vehicle accidents or crushing injuries.

o C1: unilateral injury

o C2: bilateral injuries in which one side is rotationally unstable and the controlateral side is vertically unstable

o C3: bilateral injury in which both sides are vertically unstable

Seventy to eighty percent of all pelvic injuries are type A or type B fractures[7]. (level of evidence: 4)

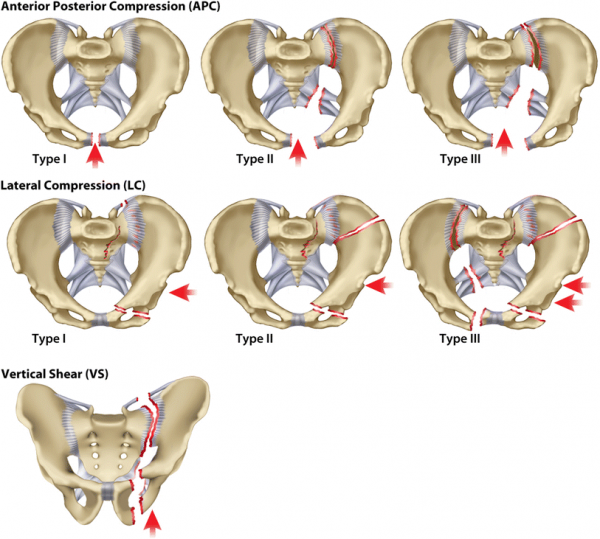

Classification of pelvic fractures by Young and Burgess is based on the mechanism of injury. [8][9][10] (level of evidence: 5, 3A, 5)

- Anterior posterior compression

- Lateral compression

- Vertical shear

- Complex: a combination of any three primary patterns

The Young and Burgess classification system is limited as it provides little guidance for treatment. [11] (level of evidence: 3A)

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Low-energy injuries are usually managed with conservative care. This included bed rest, pain control and physical therapy. <span class="fck_mw_ref" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="ref" name="3" />. Physical therapy include gait training, stabilization exercises and mobility training. [12]. Early mobilization is very important. The patient must get out of the bed as soon as possible. Prolonged immobilization can lead to a number of complications including respiratory and circulatory compromise.

The intensity of the rehabilitation depends on whether the fracture was stable or unstable. The goals of the physical therapy program should be provide the patient with an optimal return of function by improving functional skills, self-care skills and safety awareness. [13] In people with surgical treatment (ex: ORIF), after 1 or 2 days of bed rest physical therapy is initiated to begin transfer and exercise training. The short-term goals are independence with transfers and wheelchair mobility. After leaving the hospital it is easier for the patient that the physical therapist comes at home for an exercise program. The time to achieve this goals are from 2 to 6 weeks, depending on de medical status of the patient. The home exercise program include basic ROM and strengthening exercises intended to prevent contracture and reduce atrophy. The patient performs isometric exercises of the gluteal muscle and quadriceps femoris muscle, ROM exercises and upper-extremity resistive exercises (eg. Shoulder and elbow flexion and extension) until fatigued. The number of repetitions varied with every patient. The patient is still in an non-weight-bearing status. [14]

Once weight-bearing is resumed, physical therapy consisted of gait training and resistive exercises for the trunk and extremities, along with cardiovascular exercises (eg. Treadmill or bicycle training). <a _fcknotitle="true" href="Aquatherapy">Aquatherapy</a> is also good and helpful when available. <span class="fck_mw_ref" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="ref" name="6" />

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Russel G. V. Et al, Pelvic Fractures, medscape, january 2016. LOE: 5

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gruen, Gary S., et al. "Functional outcome of patients with unstable pelvic ring fractures stabilized with open reduction and internal fixation." Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 39.5 (1995): 838-845. LOE : 2B

- ↑ Tile, Marvin. "Acute pelvic fractures: I. Causation and classification." Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 4.3 (1996): 143-151. LOE: 4

- ↑ Melton LJ 3rd, Sampson JM, Morrey BF, Ilstrup D. Epidemiologic features of pelvic fractures. Clin Orthop. 1981 Mar-Apr. (155):43-7. LOE: 4

- ↑ Ooi, Chee Kheong, et al. "Patients with pelvic fracture: what factors are associated with mortality?" International journal of emergency medicine 3.4 (2010): 299-304. LOE: 2B

- ↑ Aghababian, Richard. Essentials of emergency medicine. Jones &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Bartlett Publishers, 2010. (book)

- ↑ Tile, Marvin. "Acute pelvic fractures: I. Causation and classification." Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 4.3 (1996): 143-151. LOE: 4

- ↑ Mechemm C. C. et al, Pelvic Fracture in Emergency Medicine, medscape, august 2015. LOE: 5

- ↑ Tai D. K. C. et al, Retroperitoneal Pelvic Packing in the Management of Hemodynamically Unstable Pelvic Fractures: A Level I Trauma Center Experience, J Trauma. 2011;71: E79–E86. LOE: 3A

- ↑ Flint, Lewis, and H. Gill Cryer. "Pelvic fracture: the last 50 years." Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 69.3 (2010): 483-488. LOE: 5

- ↑ Alton, Timothy B., and Albert O. Gee. "Classifications in brief: young and burgess classification of pelvic ring injuries." Clinical orthopaedics and related research 472.8 (2014): 2338. LOE : 3A

- ↑ Rebecca Gourley Stephenson, Linda J. O'Connor, Obstetric and gynecologic care in physical therapy, second edition, SLACK Incorporated, 2000 (secondary)

- ↑ Mark Dutton, Orthopaedics for the Physical Therapist Assistant, Jones &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Bartlett Publishers, 2011 (secondary)

- ↑ Hakim R. M., Gruen G. S., Delitto A., Outcomes of Patients With Pelvic-Ring Fractures Managed by Open Reduction Internal Fixation, Phys Ther. 1996;76:286-295.1 (level B)