Pelvic Fractures: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

The bony pelvis is the entire structure formed by the two hip bones, the sacrum, and the coccyx, which is attached inferiorly to the sacrum. The paired hip bones are the large, curved bones that form the lateral and anterior aspects of the pelvis. Each adult hip bone is formed by three separate bones that fuse together during the late teenage years. These bony components are the ilium, ischium and pubis. <ref>Russel G. V. Et al, Pelvic Fractures, medscape, january 2016. LOE&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 5</ref>(level of evidence: 5)<br>The stability of the pelvis relies on the integrity of the posterior weight-bearing sacroiliac complex and the transfer of weight bearing forces from the spine to the lower extremities. The [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Sacroiliac_joint SI joint ](between sacrum and ilium) transmits forces from the upper limbs and spine to the hip joints and lower limbs and vice versa. This joint also acts as a shock absorber. Several muscles influence the movement and the stability of the SI joint either through attachment to the sacrum or the ilium, or ligamentous attachment to the strong anterior and posterior SI-joint ligaments. ⅔ of the joint includes the posterior superior ligamentous section and ⅓ of the joint includes the anterior inferior synovial component. <ref>Gruen, Gary S., et al. "Functional outcome of patients with unstable pelvic ring fractures stabilized with open reduction and internal fixation." Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 39.5 (1995): 838-845. LOE&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2B</ref> (level of evidence: 2B) <ref>Tile, Marvin. "Acute pelvic fractures: I. Causation and classification." Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 4.3 (1996): 143-151. LOE: 4</ref>(level of evidence: 4)<br>The pelvis contains sliding, tilting and rotation movement components.<br>Major nerves, blood vessels, and portions of the bowel, bladder, and reproductive organs all pass through the pelvic ring. The pelvis protects these important structures from injury. It also <span style="font-size: 13.28px;">serves as an anchor for the muscles of the hip, thigh and abdomen.</span> | The bony pelvis is the entire structure formed by the two hip bones, the sacrum, and the coccyx, which is attached inferiorly to the sacrum. The paired hip bones are the large, curved bones that form the lateral and anterior aspects of the pelvis. Each adult hip bone is formed by three separate bones that fuse together during the late teenage years. These bony components are the ilium, ischium and pubis. <ref>Russel G. V. Et al, Pelvic Fractures, medscape, january 2016. LOE&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 5</ref>(level of evidence: 5)<br>The stability of the pelvis relies on the integrity of the posterior weight-bearing sacroiliac complex and the transfer of weight bearing forces from the spine to the lower extremities. The [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Sacroiliac_joint SI joint ](between sacrum and ilium) transmits forces from the upper limbs and spine to the hip joints and lower limbs and vice versa. This joint also acts as a shock absorber. Several muscles influence the movement and the stability of the SI joint either through attachment to the sacrum or the ilium, or ligamentous attachment to the strong anterior and posterior SI-joint ligaments. ⅔ of the joint includes the posterior superior ligamentous section and ⅓ of the joint includes the anterior inferior synovial component. <ref>Gruen, Gary S., et al. "Functional outcome of patients with unstable pelvic ring fractures stabilized with open reduction and internal fixation." Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 39.5 (1995): 838-845. LOE&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2B</ref> (level of evidence: 2B) <ref>Tile, Marvin. "Acute pelvic fractures: I. Causation and classification." Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 4.3 (1996): 143-151. LOE: 4</ref>(level of evidence: 4)<br>The pelvis contains sliding, tilting and rotation movement components.<br>Major nerves, blood vessels, and portions of the bowel, bladder, and reproductive organs all pass through the pelvic ring. The pelvis protects these important structures from injury. It also <span style="font-size: 13.28px;">serves as an anchor for the muscles of the hip, thigh and abdomen.</span><br> | ||

[[Image:Pelvis anatomy.jpg|700px]]<br> | |||

[[Image:Pelvis anatomy.jpg|700px]]<br> | |||

== Epidemiology/Etiology == | == Epidemiology/Etiology == | ||

Revision as of 19:33, 7 January 2017

Original Editors - Rachael Lowe

Top Contributors - Descheemaeker Kari, Julie Stainier, Lynn Wright, Jentel Van De Gucht, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Lucinda hampton, 127.0.0.1, Kim Jackson, Rosie Swift, Scott Buxton, Aminat Abolade, Siobhán Cullen, Karen Wilson, Vidya Acharya, Claire Knott and Lauren Lopez

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

We searched for information in different scientific medical databases like PubMed, Pedro and Web of Science. Also, we went to a library and lend some books.

We started our search with the following key words: pelvis, fractures, pelvic fracture, physiotherapy, rehabilitation, surgery, … We searched these words by using Mesh terms. We specified our search by looking for recent articles (publication date last five years: 2011-2016).

Definition/description[edit | edit source]

A pelvic fracture is a disruption of the bony structures of the Pelvis. An anatomic ring is formed by the fused bones of the ilium, ischium and pubis attached to the sacrum. A pelvic fracture can occur by low-energy mechanism or by high-energy impact. They can range in severity from relatively benign injuries to life-threatening, unstable fractures.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

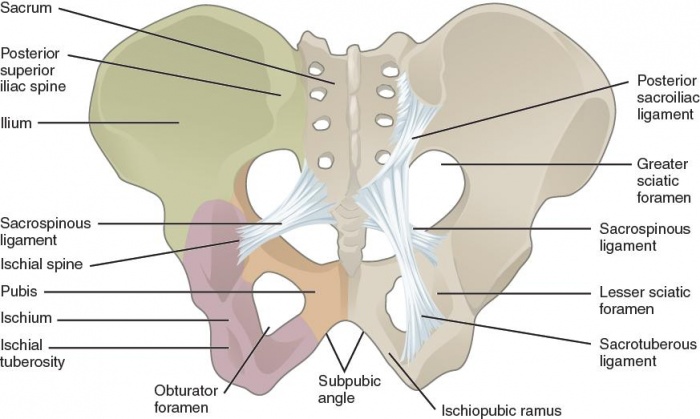

The bony pelvis is the entire structure formed by the two hip bones, the sacrum, and the coccyx, which is attached inferiorly to the sacrum. The paired hip bones are the large, curved bones that form the lateral and anterior aspects of the pelvis. Each adult hip bone is formed by three separate bones that fuse together during the late teenage years. These bony components are the ilium, ischium and pubis. [1](level of evidence: 5)

The stability of the pelvis relies on the integrity of the posterior weight-bearing sacroiliac complex and the transfer of weight bearing forces from the spine to the lower extremities. The SI joint (between sacrum and ilium) transmits forces from the upper limbs and spine to the hip joints and lower limbs and vice versa. This joint also acts as a shock absorber. Several muscles influence the movement and the stability of the SI joint either through attachment to the sacrum or the ilium, or ligamentous attachment to the strong anterior and posterior SI-joint ligaments. ⅔ of the joint includes the posterior superior ligamentous section and ⅓ of the joint includes the anterior inferior synovial component. [2] (level of evidence: 2B) [3](level of evidence: 4)

The pelvis contains sliding, tilting and rotation movement components.

Major nerves, blood vessels, and portions of the bowel, bladder, and reproductive organs all pass through the pelvic ring. The pelvis protects these important structures from injury. It also serves as an anchor for the muscles of the hip, thigh and abdomen.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Pelvic fractures have an incidence of 37 cases per 100000 person-years in the United States. The appearance of pelvic fractures is the greatest in people aged between 15-28 years. In persons younger than 35, pelvic fractures occur more in males than females. In persons older than 35, pelvic fractures occur more in females than males. In younger people pelvic fractures occur mostly as result of high-energy mechanisms, in older people they occur from minimal trauma, such as a low fall. Elderly people with <a _fcknotitle="true" href="Osteoporosis">Osteoporosis</a> have a higher risk factor. Low- energy fractures are usually stable fractures of the pelvic ring. High-energy pelvic fractures occur most commonly after motor vehicle crashes, motorcycle crashes, motor vehicles striking pedestrians and falls. This are mostly avulsion fractures of the superior or inferior iliac spines or with apophyseal avulsion fractures of the iliac wing or ischial tuberosity. <span class="fck_mw_ref" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="ref" name="2" /><span class="fck_mw_ref" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="ref" name="7" />

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with low-energy injuries usually present with a history of trauma like a fall from a standing or seated position onto a bony prominence or excessive strain on a muscle that inserts onto the <a _fcknotitle="true" href="Pelvis">Pelvis</a>. Swelling, pain, ecchymosis, erythema and focal tenderness may also be present. With avulsion injuries there is often pain associated with contraction of the involved muscles. [4]

Patients with high-energy injuries present usually after motor vehicle accidents, falls and crush injuries. In severe cases, this patients complain of pain in the pelvis, lower back pain, buttocks and/or hips. Usually they are unable to stand. Concomitant distracting injuries or intoxication may limit the reliability of the history. In patients with altered mental status or spinal neurologic deficits the presence of pelvic fractures should be assumed until it can be excluded. Physical findings include abnormal position of the lower limbs, pelvic deformity or <a _fcknotitle="true" href="Pelvic instability">Pelvic instability</a>, swelling and ecchymosis. The abdomen, perineum, genitals, rectum and lower back must be examined very carefully. <span class="fck_mw_ref" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="ref" name="3" /> High-energy fractures are often associated with severe injuries of other organs. <span class="fck_mw_ref" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="ref" name="8" />

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Low-energy injuries are usually managed with conservative care. This included bed rest, pain control and physical therapy. <span class="fck_mw_ref" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="ref" name="3" />. Physical therapy include gait training, stabilization exercises and mobility training. [5]. Early mobilization is very important. The patient must get out of the bed as soon as possible. Prolonged immobilization can lead to a number of complications including respiratory and circulatory compromise.

The intensity of the rehabilitation depends on whether the fracture was stable or unstable. The goals of the physical therapy program should be provide the patient with an optimal return of function by improving functional skills, self-care skills and safety awareness. [6] In people with surgical treatment (ex: ORIF), after 1 or 2 days of bed rest physical therapy is initiated to begin transfer and exercise training. The short-term goals are independence with transfers and wheelchair mobility. After leaving the hospital it is easier for the patient that the physical therapist comes at home for an exercise program. The time to achieve this goals are from 2 to 6 weeks, depending on de medical status of the patient. The home exercise program include basic ROM and strengthening exercises intended to prevent contracture and reduce atrophy. The patient performs isometric exercises of the gluteal muscle and quadriceps femoris muscle, ROM exercises and upper-extremity resistive exercises (eg. Shoulder and elbow flexion and extension) until fatigued. The number of repetitions varied with every patient. The patient is still in an non-weight-bearing status. [7]

Once weight-bearing is resumed, physical therapy consisted of gait training and resistive exercises for the trunk and extremities, along with cardiovascular exercises (eg. Treadmill or bicycle training). <a _fcknotitle="true" href="Aquatherapy">Aquatherapy</a> is also good and helpful when available. <span class="fck_mw_ref" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="ref" name="6" />

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Russel G. V. Et al, Pelvic Fractures, medscape, january 2016. LOE&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 5

- ↑ Gruen, Gary S., et al. "Functional outcome of patients with unstable pelvic ring fractures stabilized with open reduction and internal fixation." Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 39.5 (1995): 838-845. LOE&amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;nbsp;: 2B

- ↑ Tile, Marvin. "Acute pelvic fractures: I. Causation and classification." Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 4.3 (1996): 143-151. LOE: 4

- ↑ Richard Aghababian, Essentials of Emergency Medicine, second edition, Jones &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Bartlett Learning, 2010 (secondary)

- ↑ Rebecca Gourley Stephenson, Linda J. O'Connor, Obstetric and gynecologic care in physical therapy, second edition, SLACK Incorporated, 2000 (secondary)

- ↑ Mark Dutton, Orthopaedics for the Physical Therapist Assistant, Jones &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Bartlett Publishers, 2011 (secondary)

- ↑ Hakim R. M., Gruen G. S., Delitto A., Outcomes of Patients With Pelvic-Ring Fractures Managed by Open Reduction Internal Fixation, Phys Ther. 1996;76:286-295.1 (level B)