Parkinson's - Clinical Presentation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Basal Ganglia Function == | == Basal Ganglia Function == | ||

<div>The [[ | <div>The [[Introduction to Neuroanatomy|basal ganglia]] control well-learnt, long and complex movement sequences by coordinating or ensuring certain actions, including:</div> | ||

*Pre-movement planning and preparation | *Pre-movement planning and preparation (putting plans into actions ) | ||

*Initiation of movement | *Initiation of movement | ||

*Sequencing and timing of movement | *Sequencing and timing of movement | ||

*Maintaining cortically selected movement amplitude i.e. the frontal cortex is involved in the choice of movement, after which the basal ganglia | *Maintaining cortically selected movement amplitude i.e. the frontal cortex is involved in the choice of movement, after which the basal ganglia takes over and communicates with the other areas of the brain. The scale of a required movement is then calibrated the through sensorimotor integration. For example, a person may start to walk with normal step length but if the amplitude is incorrectly executed, their steps soon become shorten, progressing to a shuffling gait. | ||

They are also involved in the control of various non-motor behaviors, including emotions, language, decision making, procedural learning, and working memory.<ref>Simonyan K. Recent advances in understanding the role of the basal ganglia. ''F1000Res''. 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-122. </ref> | |||

== Basal Ganglia Dysfunction == | == Basal Ganglia Dysfunction == | ||

| Line 22: | Line 23: | ||

*Perseveration (repetition) in thought and action | *Perseveration (repetition) in thought and action | ||

For a person to perform activities of daily living, the basal ganglia need to be working properly. Impairment affects both mental and physical agility as described by motor and non-motor symptoms.<br> | For a person to perform activities of daily living, the basal ganglia need to be working properly. Impairment affects both mental and physical agility as described by motor and non-motor symptoms. Parkinson’s is a condition that is characterised by a decrease in dopaminergic innervation in the basal ganglia. This results in a range of motor and non-motor symptoms.<ref>Neumann WJ, Schroll H, de Almeida Marcelino AL, Horn A, Ewert S, Irmen F et al. Functional segregation of basal ganglia pathways in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2018 Sep 1;141(9):2655-69.</ref> | ||

<br> | |||

== Clinical Presentation == | == Clinical Presentation == | ||

Parkinson's was primarily thought to have motor symptoms only and the non-motor symptoms were managed separately. | |||

The main motor (movement) symptoms of Parkinson’s are: | The main motor (movement) symptoms of Parkinson’s are: | ||

# | #Tremor (involuntary shaking of parts of the body) | ||

# | #Rigidity (experienced as muscle stiffness) | ||

# | #Bradykinesia (experienced as slow movement) | ||

{{#ev:youtube|n_mGGir-NgU|300}}<ref>Jen Rodig. Parkinson's. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n_mGGir-NgU [last accessed 29/09/16] </ref> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|cxHpFWKIfGw|300}}<ref>Approach to the Exam for Parkinson's. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cxHpFWKIfGw [last accessed 20/04/19] </ref> | |||

== Progression of Parkinson's | == Progression of Parkinson's == | ||

==== Hoehn and Yahr Scale ==== | ==== Hoehn and Yahr Scale ==== | ||

| Line 44: | Line 48: | ||

The Hoehn and Yahr scale is commonly used to describe how the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s progress. | The Hoehn and Yahr scale is commonly used to describe how the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s progress. | ||

The original scale was published in a 1967 article by Melvin Yahr and Margaret Hoehn, and included stages 1 to 5<ref>Hoehn M, Yahr M (1967). "Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality." Neurology; 17 (5): 427–42</ref> | The original scale was published in a 1967 article by Melvin Yahr and Margaret Hoehn, and included stages 1 to 5.<ref>Hoehn M, Yahr M (1967). "Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality." Neurology; 17 (5): 427–42</ref> | ||

Since then, a modified Hoehn and Yahr scale has been proposed with the addition of stages 1.5 and 2.5 to help describe the intermediate course of the disease. | Since then, a modified Hoehn and Yahr scale has been proposed with the addition of stages 1.5 and 2.5 to help describe the intermediate course of the disease. | ||

[[Image:Parkinson Table 1.jpg|600px | [[Image:Parkinson Table 1.jpg|center|600px]]<br> | ||

As noted in the H&Y scale, at diagnosis, these signs are usually unilateral, but they become bilateral as the condition progresses. Later in the course of the Parkinson’s additional signs may be present including postural instability (e.g. tendency to fall backwards after a sharp pull from the examiner - the ‘pull test’) and orthostatic hypotension (OH).<br> | As noted in the H&Y scale, at diagnosis, these signs are usually unilateral, but they become bilateral as the condition progresses. Later in the course of the Parkinson’s additional signs may be present including postural instability (e.g. tendency to fall backwards after a sharp pull from the examiner - the ‘pull test’) and orthostatic hypotension (OH).<br> | ||

| Line 54: | Line 58: | ||

==== MacMahon and Thomas Scale ==== | ==== MacMahon and Thomas Scale ==== | ||

MacMahon and Thomas (1998) have provided a clinical staging classification<ref>MacMahon D, Thomas S (1998). Practical approach to quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: the nurse’s role. Journal of Neurology; 245: S19–S22</ref> | MacMahon and Thomas (1998) have provided a clinical staging classification.<ref>MacMahon D, Thomas S (1998). Practical approach to quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: the nurse’s role. Journal of Neurology; 245: S19–S22</ref> The model is based on four stages of progression from a state of gaining the-best health, through to the requirement of support and comfort - diagnosis, maintenance, complex and palliative. | ||

[[Image:Park Flow chart.jpg|center|300px]] | [[Image:Park Flow chart.jpg|center|300px]] | ||

Unlike the H and Y scale, there is more fluidity with this model, allowing for periods when the person might deteriorate during an illness, whether related to Parkinson’s or not e.g. chest infection, rehabilitation, post fall and fracture, but regains prior ability on recovery.<br> | Unlike the H and Y scale, there is more fluidity with this model, allowing for periods when the person might deteriorate during an illness, whether related to Parkinson’s or not e.g. chest infection, rehabilitation, post-fall and fracture, but regains prior ability on recovery.<br> | ||

[[Image:Parkinsons Flow Chart.png|center]]<br> | [[Image:Parkinsons Flow Chart.png|center]]<br> | ||

| Line 65: | Line 69: | ||

==== Non-motor Symptoms ==== | ==== Non-motor Symptoms ==== | ||

Non-dopaminergic and non-motor symptoms often present before the diagnosis of Parkinson’s, and almost inevitably emerge as the condition progresses.<ref>Tibar H, El Bayad K, Bouhouche A, Ait Ben Haddou EH, Benomar A et al. Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson's Disease and Their Impact on Quality of Life in a Cohort of Moroccan Patients. Front Neurol. 2018;9:170. </ref><ref>Schapira AHV, Chaudhuri KR, Jenner P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(7):435-50. </ref> They often dominate the clinical picture of advanced Parkinson's, contributing to a disability, impaired quality of life, and shortened life expectancy. | |||

Non-motor symptoms are often inadequately treated despite increased attention on the recognition and quantification of symptoms. Commonly experienced non-motor symptoms include: | |||

* '''Cognitive''': thinking, reasoning and decision making skills are usually affected. problems in multi-tasking, concentration, learning and remembering, understanding and using language, planning and carrying out activities. | |||

Non-motor symptoms are often inadequately treated despite increased attention on the recognition and | * '''Sleep problems''' and daytime tiredness | ||

* '''Mood''': depression, apathy and anxiety | |||

*depression | * '''Psychotic Symptoms''': hallucinations and delusion | ||

* | * '''Physiological''': pain, genitourinary problems, constipation, excessive sweating, drooling of saliva, restless leg syndrome and irregular heartbeat. | ||

*pain | Early identification and effective management of non‐motor symptoms may be able to enhance the quality of life of people who have Parkinson's.<ref>Huang X, Ng SY, Chia NS, Setiawan F, Tay KY, Au WL et al. Non-motor symptoms in early Parkinson's disease with different motor subtypes and their associations with quality of life. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(3):400-6. </ref> It is, therefore, important to elicit from the individual whether they have any such (or other) symptoms; this can be done using the [https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources/non-motor-symptoms-questionnaire Non-motor symptoms questionnaire]. | ||

[ | |||

Rochester et al (2013) provide an extremely useful table detailing key diagnostic criteria of various movement disorders that help us assess for and | Rochester et al (2013) provide an extremely useful table detailing key diagnostic criteria of various movement disorders that help us assess for and recognize and common features in differing conditions.<br> | ||

== Resources | == Resources == | ||

#For physiotherapy-relevant information, refer to the [ | #For physiotherapy-relevant information, refer to the [https://www.parkinsonnet.nl/app/uploads/sites/3/2019/11/eu_guideline_parkinson_guideline_for_pt_s1.pdf European Physiotherapy Guideline] for more information, including a breakdown in Table 2.5.2 on page 25 of the sub-types of Parkinson’s. | ||

#Quick Reference Cards In addition to the new Quick Reference Cards in the European Guideline, UK-specific cards can still be viewed for consideration. Reference and source: Ramaswamy B, Jones D, Goodwin V, Lindop F, Ashburn A, Keus S, Rochester L, Durrant K (2009).[http://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/download/english/quickreferencecards_physio.pdf Quick Reference Cards (UK) and Guidance Notes for physiotherapists working with people with Parkinson’s disease]. Parkinson’s Disease Society, London.<br> | #Quick Reference Cards In addition to the new Quick Reference Cards in the European Guideline, UK-specific cards can still be viewed for consideration. Reference and source: Ramaswamy B, Jones D, Goodwin V, Lindop F, Ashburn A, Keus S, Rochester L, Durrant K (2009).[http://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/download/english/quickreferencecards_physio.pdf Quick Reference Cards (UK) and Guidance Notes for physiotherapists working with people with Parkinson’s disease]. Parkinson’s Disease Society, London.<br> | ||

==== Related pages ==== | ==== Related pages ==== | ||

*[[Parkinson's | *[[Parkinson's]] | ||

*[[Parkinson's | *[[Parkinson's - Anatomy, Pathology, Prognosis and Diagnosis|Anatomy, Pathology, Prognosis and Diagnosis]] | ||

*[[Parkinson's | *[[Parkinson's - Physiotherapy Referral and Assessment|Physiotherapy - Referral and Assessment]] | ||

*[[Parkinson's | *[[Parkinson's - Physiotherapy Management and Interventions|Physiotherapy - Management and Interventions]] | ||

*[[Parkinson's | *[[Parkinson's - Key Evidence and resources|Key Evidence and resources]] | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /><br> | <references /><br> | ||

[[Category:Assessment]] [[Category:Conditions]] [[Category:Parkinson' | [[Category:Assessment]] | ||

[[Category:Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Parkinson's]] | |||

[[Category:Older_People/Geriatrics]] | |||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics - Assessment and Examination]] | |||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

[[Category:Plus Content]] | |||

Latest revision as of 08:03, 17 September 2023

Original Editor - Bhanu Ramaswamy as part of the APPDE Project

Top Contributors - Wendy Walker, Kim Jackson, Mariam Hashem, Rachael Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Jess Bell, Admin, Tony Lowe, Tarina van der Stockt, Evan Thomas and Naomi O'Reilly

Basal Ganglia Function[edit | edit source]

- Pre-movement planning and preparation (putting plans into actions )

- Initiation of movement

- Sequencing and timing of movement

- Maintaining cortically selected movement amplitude i.e. the frontal cortex is involved in the choice of movement, after which the basal ganglia takes over and communicates with the other areas of the brain. The scale of a required movement is then calibrated the through sensorimotor integration. For example, a person may start to walk with normal step length but if the amplitude is incorrectly executed, their steps soon become shorten, progressing to a shuffling gait.

They are also involved in the control of various non-motor behaviors, including emotions, language, decision making, procedural learning, and working memory.[1]

Basal Ganglia Dysfunction[edit | edit source]

Basal ganglia dysfunction affects the automatic (involuntary) nature of our movements. This includes:

- Impaired performance of well-learnt motor skills and movement sequences

- Problems maintaining sufficient movement amplitude

- Difficulty in performing more than one task simultaneously (dual-tasking)

- Difficulty in shifting motor and cognitive sets

- Slower mental processing

- Perseveration (repetition) in thought and action

For a person to perform activities of daily living, the basal ganglia need to be working properly. Impairment affects both mental and physical agility as described by motor and non-motor symptoms. Parkinson’s is a condition that is characterised by a decrease in dopaminergic innervation in the basal ganglia. This results in a range of motor and non-motor symptoms.[2]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Parkinson's was primarily thought to have motor symptoms only and the non-motor symptoms were managed separately.

The main motor (movement) symptoms of Parkinson’s are:

- Tremor (involuntary shaking of parts of the body)

- Rigidity (experienced as muscle stiffness)

- Bradykinesia (experienced as slow movement)

Progression of Parkinson's[edit | edit source]

Hoehn and Yahr Scale[edit | edit source]

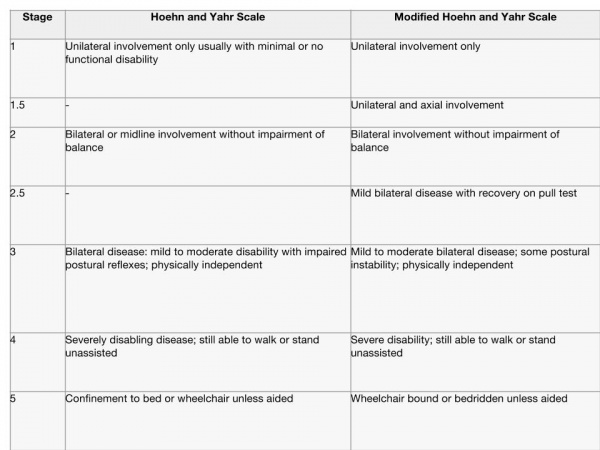

The Hoehn and Yahr scale is commonly used to describe how the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s progress.

The original scale was published in a 1967 article by Melvin Yahr and Margaret Hoehn, and included stages 1 to 5.[5]

Since then, a modified Hoehn and Yahr scale has been proposed with the addition of stages 1.5 and 2.5 to help describe the intermediate course of the disease.

As noted in the H&Y scale, at diagnosis, these signs are usually unilateral, but they become bilateral as the condition progresses. Later in the course of the Parkinson’s additional signs may be present including postural instability (e.g. tendency to fall backwards after a sharp pull from the examiner - the ‘pull test’) and orthostatic hypotension (OH).

MacMahon and Thomas Scale[edit | edit source]

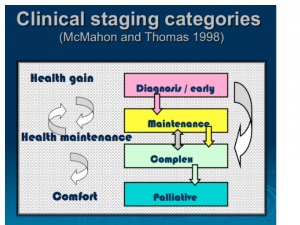

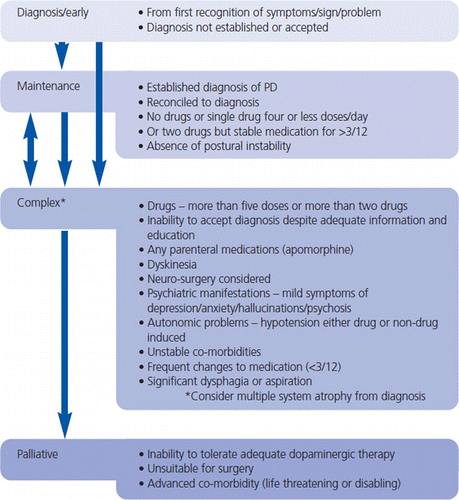

MacMahon and Thomas (1998) have provided a clinical staging classification.[6] The model is based on four stages of progression from a state of gaining the-best health, through to the requirement of support and comfort - diagnosis, maintenance, complex and palliative.

Unlike the H and Y scale, there is more fluidity with this model, allowing for periods when the person might deteriorate during an illness, whether related to Parkinson’s or not e.g. chest infection, rehabilitation, post-fall and fracture, but regains prior ability on recovery.

Non-motor Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Non-dopaminergic and non-motor symptoms often present before the diagnosis of Parkinson’s, and almost inevitably emerge as the condition progresses.[7][8] They often dominate the clinical picture of advanced Parkinson's, contributing to a disability, impaired quality of life, and shortened life expectancy.

Non-motor symptoms are often inadequately treated despite increased attention on the recognition and quantification of symptoms. Commonly experienced non-motor symptoms include:

- Cognitive: thinking, reasoning and decision making skills are usually affected. problems in multi-tasking, concentration, learning and remembering, understanding and using language, planning and carrying out activities.

- Sleep problems and daytime tiredness

- Mood: depression, apathy and anxiety

- Psychotic Symptoms: hallucinations and delusion

- Physiological: pain, genitourinary problems, constipation, excessive sweating, drooling of saliva, restless leg syndrome and irregular heartbeat.

Early identification and effective management of non‐motor symptoms may be able to enhance the quality of life of people who have Parkinson's.[9] It is, therefore, important to elicit from the individual whether they have any such (or other) symptoms; this can be done using the Non-motor symptoms questionnaire.

Rochester et al (2013) provide an extremely useful table detailing key diagnostic criteria of various movement disorders that help us assess for and recognize and common features in differing conditions.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- For physiotherapy-relevant information, refer to the European Physiotherapy Guideline for more information, including a breakdown in Table 2.5.2 on page 25 of the sub-types of Parkinson’s.

- Quick Reference Cards In addition to the new Quick Reference Cards in the European Guideline, UK-specific cards can still be viewed for consideration. Reference and source: Ramaswamy B, Jones D, Goodwin V, Lindop F, Ashburn A, Keus S, Rochester L, Durrant K (2009).Quick Reference Cards (UK) and Guidance Notes for physiotherapists working with people with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Disease Society, London.

Related pages[edit | edit source]

- Parkinson's

- Anatomy, Pathology, Prognosis and Diagnosis

- Physiotherapy - Referral and Assessment

- Physiotherapy - Management and Interventions

- Key Evidence and resources

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Simonyan K. Recent advances in understanding the role of the basal ganglia. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-122.

- ↑ Neumann WJ, Schroll H, de Almeida Marcelino AL, Horn A, Ewert S, Irmen F et al. Functional segregation of basal ganglia pathways in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2018 Sep 1;141(9):2655-69.

- ↑ Jen Rodig. Parkinson's. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n_mGGir-NgU [last accessed 29/09/16]

- ↑ Approach to the Exam for Parkinson's. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cxHpFWKIfGw [last accessed 20/04/19]

- ↑ Hoehn M, Yahr M (1967). "Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality." Neurology; 17 (5): 427–42

- ↑ MacMahon D, Thomas S (1998). Practical approach to quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: the nurse’s role. Journal of Neurology; 245: S19–S22

- ↑ Tibar H, El Bayad K, Bouhouche A, Ait Ben Haddou EH, Benomar A et al. Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson's Disease and Their Impact on Quality of Life in a Cohort of Moroccan Patients. Front Neurol. 2018;9:170.

- ↑ Schapira AHV, Chaudhuri KR, Jenner P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(7):435-50.

- ↑ Huang X, Ng SY, Chia NS, Setiawan F, Tay KY, Au WL et al. Non-motor symptoms in early Parkinson's disease with different motor subtypes and their associations with quality of life. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(3):400-6.