|

|

| (45 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) |

| Line 2: |

Line 2: |

| '''Original Editor '''- [[User:David Greaves|David Greaves]], [[User:Lynette Fox|Lynette Fox]], and [[User:Katie White|Katie White]] as part of the [[Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project]] | | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:David Greaves|David Greaves]], [[User:Lynette Fox|Lynette Fox]], and [[User:Katie White|Katie White]] as part of the [[Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project]] |

|

| |

|

| '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} <br> |

| </div> | | </div> |

| ==== Aims ====

| |

|

| |

|

| To increase the awareness and understanding of the role of pain neuroscience education in the management of patients with [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Chronic_Low_Back_Pain chronic low back pain] (LBP), by providing information and resources to its current use clinically. This resource is primarily aimed towards physiotherapists and student physiotherapists, using a combination of visual and textual resources.

| | == Introduction == |

| | [[File:PNE.webp|right|frameless|234x234px]] |

| | Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts more than three months. It is a very common and prevalent problem that affects most age groups worldwide. Chronic pain is a multifactorial disorder that is influenced by biology, psychology, environmental, and social factors.<ref>Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019 Aug;123(2):e273-e283.</ref> Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) is a strategy that aims to teach patients to reshape their mindset and perception of [[Pain Behaviours|pain]] despite these factors. It provides patients a better understanding of their condition and motivates them to become active participants in their treatment programs. |

|

| |

|

| ===== Learning objectives: =====

| | Based on a large number of high-quality studies, it has been shown that teaching people with chronic pain more about the neuroscience of their pain produces immediate and long-term changes. PNE has been shown to have positive effects in reducing pain, disability, and psychosocial problems, improving patient's knowledge of pain mechanisms, facilitating movement and decreasing healthcare consumption.<ref>Zimney KJ, Louw A, Cox T, Puentedura EJ, Diener I. Pain neuroscience education: Which pain neuroscience education metaphor worked best?. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2019 Jan 1;75(1):1-7. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6739553/<nowiki/>(accessed 19.4.2022)</ref> |

|

| |

|

| 1. To gain an understanding of the history and development of Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) as a therapeutic concept.<br>2. To develop a greater understanding of PNE; what it is and how it is used in clinical practice<br>3. To develop an understanding of how PNE is currently being taught to student and qualified physiotherapists<br>4. To gain increased awareness of the evidence base available and the applicability of the findings to clinical practice<br>

| | == Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) == |

|

| |

|

| ==== Introduction ==== | | With respect to PNE, [[Chronic Pain and the Brain|chronic pain]] is not viewed as a result of unhealthy or dysfunctional tissues. Rather, it is due to [[Neuroplasticity|brain plasticity]] leading to hyper-excitability of the central nervous system, known as central sensitization.<ref name=":1">Nijs J, Girbés EL, Lundberg M, Malfliet A, Sterling M. Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Manual therapy. 2015; 20 (1): 216-220.</ref> The ultimate goal for Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) is to increase pain tolerance with movement (e.g., be able to perform exercise with mild discomfort), reduce any fear associated with movement, and reduce central nervous system hypersensitivity. In practice, this often includes the use of educational pain analogies, re-education of patient misconceptions regarding disease pathogenesis, and guidance about lifestyle and movements modifications that can be introduced. |

|

| |

|

| Low back pain (LBP) is currently considered to be the most common cause of disability and time off work in the over 45 age group, with it being reported that 84% people will experience LBP at some point during their life.<ref>Balagué F, Mannion AF, Pellisé F, Cedraschi C. Non-specific low back pain. The Lancet. 2012;4(379): 482-91.</ref> Whilst LBP is generally considered a self-limiting condition it can have severe implications to the patient’s psychological and physical health. Results from a UK survey, analysing the consultation prevalence for LBP showed that 417 per 10 000 registered patients sought medical help for their LBP, with the highest numbers being seen in the 45- 64 age group (536 per 10 000).<ref name=":0">Jordan KP, Kadam UT, Hayward R, Porcheret M, Young C, Croft P. Annual consultation prevalence of regional musculoskeletal problems in primary care: an observational study. BMC Musculoskeletal disorders. 2010;11 (144). Doi 10.1186/1471-2474-11-144</ref> However study data was only drawn from one area of the United Kingdom, including 100,000 patients, thus this area may not be generalisable to the United Kingdom as a whole. Furthermore the study only considered patients reporting their pain to a General Practitioner, so only measured patients who seeking health care advice thus failed to consider the whole population suffering LBP.<ref name=":0" /> Further to this, an Australian cohort study discovered whilst most patient’s recovered 1/3 had not fully recovered after 1 year.<ref>Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J. et al. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ. 2008; 337 (a171).</ref> LBP is clearly a substantial problem for both the health system and the socioeconomic environment, thus effective management is critical.<br>

| | There are two clinical indications for initiating Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)<ref name=":2">Nijs, J., Paul van Wilgen, C., Van Oosterwijck, J., van Ittersum, M., Meeus, M.,How to explain central sensitization to patients with ‘unexplained’ chronic musculoskeletal pain: Practice guidelines, Manual Therapy, 2011, 16:5, 413-418</ref>: |

|

| |

|

| Updated NICE guidelines for Chronic LBP states that information and self-care advice should be provided to patients to promote self-management by fostering a positive attitude and providing realistic expectations to patients. However the type, duration, frequency and content of this advice was not reported on.<ref>National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Back pain - low (without radiculopathy). Clinical Knowledge Summary. London: NICE.2015</ref>

| | * the clinical picture is dominated by central sensitization |

| | * illness coping mechanisms or poor illness perception is present |

| | [[Image:Effects_of_central_sensatisation.png|313x313px|alt=|thumb|Effects of central sensitization]] |

|

| |

|

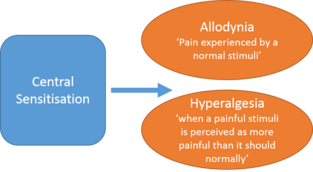

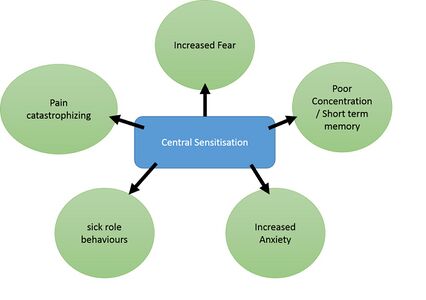

| ==== What is Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)? ==== | | Central sensitization is when there is amplification of pain in the central nervous system. It can result in hypersensitivity to stimuli, responsiveness to non-noxious stimuli, and increased pain response evoked by stimuli outside the area of injury, an expanded receptive field. <ref>[[Central Sensitisation]]</ref>This can be assessed during the subjective and objective portion of a patient's evaluation. A physical therapist can determine what a patient's perception of their own pain is and how they cope with their pain. [[File:Upload_version_of_systemic_effects.jpg|alt=|thumb|426x426px|Pain behaviors caused by central sensitization]]PNE aims to reconceptualize pain to patients with these four main points: |

| | * Pain does not provide a measure of the state of the tissues |

| | * Pain is modulated by many factors from somatic, psychological, and social domains |

| | * The relationship between pain and the state of tissues becomes less predictable as pain persists |

| | * Pain can be conceptualized as the conscious correlate of the implicit perception that tissue is in danger<ref name=":0">Moseley GL. Reconceptualising pain according to modern pain science. Physical therapy reviews. 2007 Sep 1;12(3):169-78.</ref> |

|

| |

|

| Pain neuroscience education (PNE), also known as therapeutic neuroscience education (TNE), consists of educational sessions for patients describing in detail the neurobiology and neurophysiology of pain and pain processing by the nervous system.<ref>Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2011; 92(12):2041-2056.</ref><br>This educational approach has been used by physiotherapists therapeutically since 2002 in various countries including the UK, US and Australia and differs considerably from traditional education strategies such as back school and biomechanical models.<ref name=":4">Clarke CL, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. Pain neurophysiology education for the management of individuals with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Manual therapy. 2011; 16(6):544-549.</ref> This is due to how likelihood of pain chronicity (e.g. for an MSK condition) may not likely be caused by unhealthy or dysfunctional tissues but brain plasticity leading to hyper-excitability of the central nervous system, known as central sensitisation.<ref name=":1">Nijs J, Girbés EL, Lundberg M, Malfliet A, Sterling M. Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Manual therapy. 2015; 20 (1): 216-220.</ref> Therefore, a deeper level reasoning and treatments beyond a medical model is required.

| | == Application of PNE == |

| | The application of PNE is most useful as part of a combination therapy for chronic pain that includes physiotherapy intervention (including [[Therapeutic Exercise|exercise therapy]]) and may or may not include [[Pain Medications|pharmacological treatment]]. Its application is best applied by trained and skilled clinicians with experience in managing patients with chronic pain conditions. Overall, PNE serves as a method of reconceptualizing a patient's perception of their pain experience, providing an avenue for reducing pain, disability and improving [[Quality of Life|quality of life]]<ref name=":0" />. PNE puts the complex process of describing the nerves and brain into a format that is easy to understand for everyone regardless of age, educational level, or ethnic group.<ref name=":10">Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2011; 92(12):2041-2056.</ref>{{#ev:youtube|?v=6RGP_usIbBU|width}}<ref>Pain Neuroscience Education PAINWeek |

| | Available:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6RGP_usIbBU (accessed 19.4.2022)</ref> |

|

| |

|

| [[Image:Education_PNE.jpg|center|300x300px]] | | Methods of PNE delivery vary but can typically involve around 4 hours of teaching that is provided to a group or individually, either in single or multiple sessions.<ref name=":4">Clarke CL, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. Pain neurophysiology education for the management of individuals with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Manual therapy. 2011; 16(6):544-549.</ref>PNE consists of educational sessions for patients describing in detail the neurobiology and neurophysiology of pain and [[Pain Facilitation and Inhibition|pain processing]] by the [[Introduction to Neuroanatomy|nervous system]].<ref name=":10" /> It is implemented prior to administering physical therapy interventions with a verbal explanation. This is subsequently reinforced throughout the course of treatment to ensure proper carryover of reconceptualization of pain during and after discharge from physical therapy. |

|

| |

|

| Initially, PNE changes a patient’s perception of pain. For example, a patient may have believed that damaged tissues were the main cause for their pain, and by receiving education about pain neurophysiology the patient understands that pain may not correctly represent the health of the tissue, but may be due to extra-sensitive nerves. As a result, patients have been found to have a reduction in fear avoidance behaviours and are more able and willing to move. PNE can be used with a combination of treatments, including exercise therapy that can be used to break down movement-related pain memories with graded exposure to exercise and decrease sensitivity of the nervous system.<ref name=":1" /><br>What is central sensitisation?

| | During the first educational session, the clinician should explain central sensitization along with the use any of the following: pictures, booklets, pamphlets, metaphors, drawings, question/answer assignments, and neurophysiology pain questionnaires. Topics addressed include acute pain vs. chronic pain, how it evolves from acute pain to chronic pain, interpretation of stimuli to the nervous system, and external factors that may impact pain (such as anxiety, stress, depression, pain perceptions, and behavior). Patients are encouraged to read the handouts or brochures handed to them from the clinician at home.<ref name=":2" /> |

|

| |

|

| Central sensitisation is a neural condition developing from plastic changes that occur within the central nervous system (spinal cord), causing the manifestation of chronic pain.<ref name=":2">McAllister MJ. Central Sensitization. 2012. Available from: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/understanding-chronic-pain/what-is-chronic-pain/central-sensitization<nowiki/>(accessed 16 January 2016).

| | During subsequent sessions, the patient is encouraged to ask questions and receive clarification for any questions they may have about the neurophysiology of their pain. The clinician can address psychosocial aspects of a patient's pain during any visit. Some examples of clinically indicated advice that can be provided include advising the patient to stop worrying about their pain, reduce stress, implement relaxation techniques, and become more physically active. The treatment rationale should be provided throughout the patient's plan of care. Continually reinforcing and educating the patient regarding their pain physiology is recommended. The overarching goal is to motivate and encourage the patient to complete their treatment program in order to achieve their functional goals. <ref name=":2" /> |

| </ref> Theory of central sensitisation explains that spinal neurons are in state of hyperexcitability with lower nociceptive threshold.<ref>Schaible HG, Richter F. Pathophysiology of pain. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2004; 389(4):237-243.</ref> Additionally, peripheral inputs from not only A δ and C fibres but also innocuous Aβ mechanoreceptor fibres of injured and adjacent non-injured tissues, increase summation of action potentials at the dorsal root ganglion as pictured below:

| |

|

| |

|

| [[Image:Sensitisation2.png|350x550px|Figure 3: normal neural activity vs spinal neurones in a state of hyper-excitability (Sciable and Richter, 2004)]][[Image:Effects_of_central_sensatisation.png|right|300x200px]]

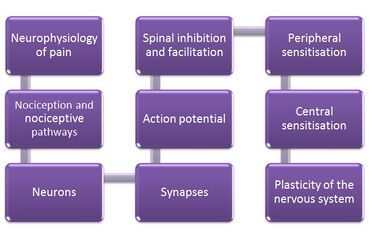

| | Figure 4. illustrates the content of PNE education sessions with patients<ref name=":10" /> |

|

| |

|

| Figure 4:Systemic effects of central sensitisation<ref name=":2" /> | | [[Image:Methods of PNE.jpg|center|Figure 4. displays the content of PNE education sessions|alt=Figure showing the content of PNE education sessions|369x369px]] |

|

| |

|

| These plastic changes cause a state of persistent hyper-sensitivity to develop, even after tissue healing has occurred. Thus the patient continues to experience pain, even with less provocation<ref name=":2" />. The theory of central sensitisation was highlighted in the 1960’s, when the pain gate theory advocated that the sensory relay system could be modulated by inhibitory controls (pressure).<ref name=":3">Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152(3):2-15.</ref> <br>Central sensitization also involves changes in the brain at cellular level<ref name=":2" />. However other research has suggested that sensitization may develop from: activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, gap junctions, astrocytes, membrane excitability and gene transcription.<ref name=":3" /><br>Whilst it has long been recognised that Strokes and Spinal Cord injuries can cause central sensitization, it is not fully understood why it may develop following musculoskeletal injury<ref name=":2" />. However it has been proposed that there may be one of two reasons for its development, although there is no conclusive evidence to support this:<ref name=":2" /><br>Pre-existing factors (genetics) that may predispose an individual to have altered central nervous system functioning following injury<br>Factors (environmental) that may cause altered central nervous system functioning once injury has occurred. i.e. (anxiety, stress, depression, fear-avoidance and poor sleep)<br>[[Image:Upload_version_of_systemic_effects.jpg|Figure 4:Systemic effects of central sensitisation (McAllister, 2012)]]

| | An example of a metaphor or story that can be used with patients is provided here: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education. |

|

| |

|

| Figure 5: Pain behaviours caused by central sensitisation

| | === PNE for Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions<ref name=":13">Moseley GL, Butler DS. Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(9):807-813.</ref> === |

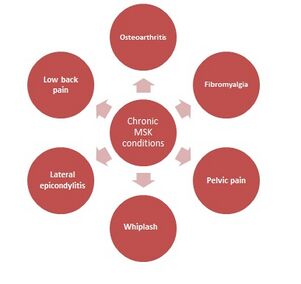

| | [[Image:Chronic MSK conditions.jpg|alt=|thumb|Chronic MSK conditions with positive PNE results |301x301px]]These conditions are often characterised by brain plasticity that leads to hyperexcitability of the central nervous system (central sensitisation). Figure 5 highlights chronic musculoskeletal conditions that benefit from PNE, including osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, pelvic pain, whiplash, lateral epicondylitis, and low back pain.<ref name=":6">Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2014; 39(18):1449-1457.</ref><ref name=":7">Zimney K, Louw A, Puentedura EJ. Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014; 30(3):202-209.</ref> |

|

| |

|

| ==== History of pain models and development of PNE ====

| | Recent studies suggest that PNE in conjunction with either therapeutic exercise or manual therapy yielded significant reduction in pain ratings.<ref>Louw, A., Zimney, K., Puentedura, E., Diener, I., The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature, Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 2016, 32:5, 332-355.</ref> |

|

| |

|

| ===== Where has PNE developed from? =====

| |

|

| |

|

| The biomedical model is most commonly used by physiotherapists and other medical health professionals for the management of pain.<ref>Linton SJ. Models of pain perception. Understanding Pain for Better Clinical Practice: A Psychological Perspective. Elsevier, 2005. p9-18.</ref><ref name=":5">Louw A. Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching People About Pain. 2014. Available from: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education. (accessed 6 Janurary 2016). </ref> The model follows that pain and injury interrelated, thus an increase in pain means further tissue damage have occurred and vice-versa.<ref name=":5" /> This model, called the Cartesian model, is over 450 years old, and many argue inaccurate and significantly outdated.<ref name=":5" />

| |

|

| |

|

| [[Image:Rene Descartes.jpg|150x200px|Figure 1: Cartesian theory of pain stating that pain to the brain is a “straight line” (Lower-back-pain-toolkit.com, 2015)]]<br>

| | == References == |

| | <references /> |

|

| |

|

| Figure 1: Cartesian theory of pain stating that pain to the brain is a “straight line” (Lower-back-pain-toolkit.com, 2015)

| | |

| | | [[Category:Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project]] |

| The Cartesian ‘mid-body’ was first proposed in the early 16th Century by the French Philosopher, Mathematician and Scientist Rene Descartes, in an attempt to show that humans were a mechanical body controlled by a rational soul (Linton, 2005). Descartes model proposed that the brain was the centre of senses, receiving hollow nerve tubes through which free spirits flowed. Nerves were connected to the brain as a piece of rope may be connected to an alarm; thus as pulling of the rope would cause

| | [[Category:Lumbar Spine]] |

| | | [[Category:Lumbar Spine - Interventions]] |

| ==== Why is the model considered outdated? ====

| | [[Category:Interventions]] |

| | | [[Category:Pain]] |

| Descartes model continues to be used in current medical practice and influences the perception that all pain is a result of injury and tissue damage (Linton, 2005). Clinicians frequently use the biological model to explain patient’s pain, describing pain as being due to either disc, joint or abnormal movement pattern (Louw, 2014). The resulting treatment is therefore focused on addressing the abnormal movement pattern or faulty tissue, and the pain goes away. However research has shown that education using words such as “bulging”, “herniated” and “ruptured” actually increases patient's levels of fear and anxiety, resulting in protected movements and lack of exercise compliance (Louw, 2014).

| |

| | |

| However Descartes biomedical model has been questioned in recent years, with critics arguing that it fails to consider the perception of pain from the nervous system, as well as the psychological and social factors that may influence recovery (Linton, 2005). Furthermore both psychiatrists and behavioural scientists have highlighted specific medical examples to further question the validity of Descartes model. The examples below suggest that pain may potentially be a phenomenon more than just nociception, and may have a neurological element:

| |

| | |

| *Pain was not expressed by a soldier injured in war until reaching the hospital (Goldberg, 2008)

| |

| *Similar injuries in different patients caused substantially different pain responses (Goldberg, 2008)

| |

| *An incision to the skin twice as deep as that of another, does not hurt twice as much (Goldberg, 2008)

| |

| *Why 40% of people with horrific injuries felt either no or a low intensity of pain (Melzack, Wall & Ty. 1982)

| |

| *Why up to 70% of people's do not report pain or associated symptoms consistent with their X-ray/ MRI finding (Bhattacharyya et al., 2003; Boden et al., 1990)

| |

| *Why 51% of amputees reported phantom pain and 76% phantom sensations including: cold, electric sensations and movement in the phantom limb (Kooijmana, 2000).

| |

| | |

| Furthermore in Beecher’s (1956) comparison study of 150 male civilian patients in contrast to wartime casualties, it was discovered that 83% in the civilian group requested narcotics, whilst only 32% of military patients with the same extent of tissue damage asked for them; thereby suggesting the level of pain experienced is patient dependent. This example therefore proposes that the patient's beliefs emotions and past experiences of pain can alter the brains interpretation of the pain. However the validity of study findings must be questioned, as investigations were conducted 60 years ago, thus may be significantly outdated. Furthermore the study did not consider the effect of shock or adrenaline, which has been proposed to influence immediate pain responses.

| |

| | |

| ===== The Pain-neuroscience education model =====

| |

| | |

| In the last century Descartes biomedical model has been replaced by the [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Biopsychosocial_Model biopsychosocial model] of [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Chronic_Pain chronic pain] (Goldberg, 2008), in which pain is classified as being due to increased sensitivity of the nervous system rather than further injury (Louw, 2014). In layman’s terms, pain persists after tissue healing, due to the fact that the body’s alarm system remains activated, and are stimulated by a much lower intensity of stimulus (Louw, 2014); i.e. a much lower degree of movement provocation causes pain.

| |

| | |

| ===== How does this affect clinicians in practice? =====

| |

| | |

| Investigations by the Therapeutic Neuroscience research team at the ‘International Spine and Pain Institute’ has discovered that people in pain are interested in pain and more specifically the mechanisms of pain (Louw A, Louw Q & Crous LC. 2009). Thus, current treatment for patients with chronic pain should have a greater focus on educating patients about the neuroscience of their pain, rather than classifying their pain as being due to faulty movement patterns or damaged tissues.

| |

| | |

| ==== Video of alarm systems: ====

| |

| | |

| {{#ev:youtube|hxTkm_YqJbs}}

| |

| | |

| ===== What does PNE consist of / involve? =====

| |

| | |

| PNE first of all puts the complex process of describing the nerves and brain into a format that is easy to understand for everyone; no matter whether the target audience is of a particular age, educational level or ethnic group (louw et al., 2011).

| |

| | |

| This is made possible by using simplified scientific language used with additional methods of presenting information that may include the use of:<br>'''• Simple pictures<br>• Examples<br>• Booklets<br>• Metaphors<br>• Drawings<br>• Workbook with reading/question-answer assignments<br>• Neurophysiology Pain Questionnaires'''

| |

| | |

| Methods of PNE delivery vary but can typically involve around 4 hours of teaching that is provided to a group or individually, either in single or multiple sessions (Clarke et al., 2011).<br>

| |

| | |

| Figure 6. showing the content of PNE education sessions with patients (Louw et al., 2011)<br>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Methods of PNE.jpg|center|Figure showing the content of PNE education sessions]]<br>

| |

| | |

| ===== How is PNE used in clinical practice? =====

| |

| | |

| A metaphor/story that can be found here: (http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education) is used by Louw et al., (2014) in clinical practice to teach patients about complex pain physiology including extra-sensitive nerves, inflammation, injury and how pain is created in the brain. It is such an example that helps patient to break away from a view of a particular tissue being the issue (e.g. generative disc) and helps the patient think towards the problem being related to pain and a sensitive nervous system (Louw et al., 2014). Therefore, Instead of pain following spinal surgery being seen as the ‘problem has not resolved’ or ‘there is something still wrong with the disc’, PNE would explain pain is sensitive to act as a protector which is perfectly normal after surgery. <br>

| |

| | |

| ==== Video interview of low back pain from a patients point of view ====

| |

| | |

| {{#ev:youtube|a9f6VJtls2E}}<br>

| |

| | |

| ==== Indicators for the use of PNE ====

| |

| | |

| '''Chronic musculoskeletal conditions (Moseley, 2015)'''[[Image:Chronic MSK conditions.jpg|right]]<br>

| |

| | |

| *These conditions are often characterized by brain plasticity that leads to hyperexcitability of the central nervous system (central sensitization).

| |

| *PNE is recommended in<br>central sensitization conditions like these,<br>as the patient may present with maladaptive<br>cognitions, behavior, or coping<br>strategies in response to pain.

| |

| *Typically they acquire a protective (movement-related) pain memory, which causes a barrier to adhere to therapeutic treatment such as exercise, decreasing the likelihood of a good outcome.

| |

| *Therefore these maladaptive behaviours, central sensitisation and previous failed treatments are all indicators for PNE <br>

| |

| *Evidence showing benefits for pre op MSK patients.<ref name=":6">Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2014; 39(18):1449-1457.</ref><ref name=":7">Zimney K, Louw A, Puentedura EJ. Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014; 30(3):202-209.</ref>

| |

| | |

| <br>

| |

| | |

| Figure 7. (right): showing chronic MSK conditions with positive PNE results from current evidence.<ref>Moseley GL, Butler DS. Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(9):807-813.</ref>

| |

| | |

| ==== The benefits and drawbacks of PNE ====

| |

| | |

| ==== <span style="font-size: 13.28px; line-height: 1.5em;">Table 1: showing the benefits and drawbacks of PNE</span><ref name=":6" /><ref>Moseley GL. Joining forces–combining cognition-targeted motor control training with group or individual pain physiology education: a successful treatment for chronic low back pain. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2003; 11(2):88-94. .

| |

| </ref><ref>Moseley GL. Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. European Journal of Pain. 2004; 8(1):39-45. .

| |

| </ref> ====

| |

| {| width="200" border="1" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1"

| |

| |-

| |

| | '''Benefits'''

| |

| | '''Drawbacks'''

| |

| |-

| |

| | RCT's have shown a reduction in fear and catastrophizing, due to the immediate effect of PNE on improving attitudes and beliefs about pain.

| |

| | Evidence suggests PNE alone is not a viable intervention for pain and disability

| |

| |-

| |

| | Positive effect on disability and physical performance

| |

| | Provides concerns regarding healthcare cost

| |

| |-

| |

| | Increased pain thresholds during physical tasks

| |

| | Less availability of such specialized education to patients in remote regions

| |

| |-

| |

| | Improved adherence and outcomes of therapeutic exercises

| |

| | "in clinic" attendance issues arise for patients with time and financial constraints

| |

| |-

| |

| | May reconceptualise the patients' beliefs on physiotherapy

| |

| | Clinicians need to be trained in PNE competencies

| |

| |-

| |

| | Improved passive and active range of motion

| |

| | Long term effects are not as significant as short term

| |

| |-

| |

| | No harmful effects

| |

| | Future research required on the notion of individual and group curricula; e.g. what is taught, how it is taught and measured

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| <br>

| |

| | |

| <br>

| |

| | |

| ==== '''Brain activity clinical imaging of PNE effect''' ====

| |

| | |

| Types of brain activity imaging

| |

| | |

| There are various types of brain imaging to show brain activity in pain states, some scans of which are pictured below:

| |

| | |

| [[Image:PET, MRS and fMRI.png]]

| |

| | |

| Figures 8 - 10: left to right are Positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of pain.<ref>Sharma NK, Brooks WM, Popescu AE, VanDillen L, George SZ, McCarson KE, et al. Neurochemical analysis of primary motor cortex in chronic low back pain. Brain sciences. 2012; 2(3):319-331.</ref><ref name=":8">Cole LJ, Farrell MJ, Duff EP, Barber JB, Egan GF, Gibson SJ. Pain sensitivity and fMRI pain-related brain activity in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2006; 129(11):2957-2965.</ref><ref>Casey KL, Morrow TJ, Lorenz J, Minoshima S. Temporal and spatial dynamics of human forebrain activity during heat pain: analysis by positron emission tomography. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;85(2):951-959.</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===== '''Effects of PNE imaged''' =====

| |

| <br>By teaching a patient more about how pain works with reassurance that pain doesn’t always mean tissue damage, their pain eases considerably and they experience other benefits including increased movement, better function and reduced fear avoidance. The effects of decreased pain reltaed brain activity are measurable via brain imaging as demonstrated in the example below:

| |

| | |

| A high-level dancer who was scheduled for back surgery in two days due to experiencing significant back pain for almost two years, was scanned using fMRI. Areas of brain activity related to pain were demarcated in red.

| |

| | |

| Figure 11: row 1 - patient relaxing. Note no red areas. <br>[[Image:FMRI row 1.png]]<br>

| |

| | |

| <br>

| |

| | |

| Figure 12: row 2 - patient was asked her to move her painful back while in the scanner. These images demonstrated brain activity related to pain whereby larger areas of red signifies more pain related activity, hence more pain.

| |

| | |

| [[Image:FMRI row 2.png]]<br> | |

| | |

| <br>

| |

| | |

| Figure 13: row 3 - after initial scans the patient was taken out of the scanner and provided with a teaching session about pain for 20-25 minutes. Following this, the scan of the patient was immediately repeated doing the same painful task as performed in Row 2. Note this time however, there was significantly less activity (fewer red areas) despite performing the same movement.<ref name=":6" /><br>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:FMRI row 3.png]]<br>

| |

| | |

| There is an obvious link with patient catastrophising thoughts and pain related brain activity, shown by the immediate reduction in brain activity following PNE provision in the above example. Furthermore, there is a link in attention to pain that when negatively perceived, impacts on the experience of pain being greater. One study<ref name=":8" /> demonstrated that pain related brain activity was greater in pts with Alzheimer’s, than age matched healthy controls. However, in this population there is less reporting of pain and analgesic use. Is this due to difficulty to communicate pain or due to reduced attention to pain?

| |

| | |

| ==== Current training provided in PNE ====

| |

| | |

| Firstly it is presumed that PNE as a first line cognitive behavioural therapy can be implemented by any healthcare professional. Zimney, Louw and Puentedura explain that the key to successfully using PNE, is to provide timely intervention for only those patients that present with both pain and maladaptive cognitive pain behaviours together<ref name=":7" />. This requires a level of understanding of pain mechanisms, [http://www.physio-pedia.com/The_Flag_System yellow flags and blue flags]. Health professionals are in a prime position to deliver PNE, as they are the first point of contact for patients that are experiencing health concerns exceeding their own capability to self-manage.

| |

| | |

| ===== Undergraduate training =====

| |

| | |

| PNE is not currently delivered in undergraduate courses for medical or physiotherapy professions and there is an obvious lack of understanding of the non-tissue related causes of pain, and its appropriate management. The table below demonstrates the undergraduate stance on understanding of chronic pain management at time of reporting in 2009. This was assessed by way of questionnaires provided to third year physiotherapy and medical students.

| |

| | |

| Table 2. Results from questionnaire of medical and physiotherapy students chronic pain knowledge<ref name=":9">Ali N,Thomson D. A comparison of the knowledge of chronic pain and its management between final year physiotherapy and medical students. European Journal of Pain. 2009; 13(1):38-50.</ref>.

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Education of undergraduate students crop.png]]<br>

| |

| | |

| The box and whisker plots in figure 14 illustrate the differences between medical and physiotherapy students in management and knowledge of chronic pain.

| |

| | |

| Figure 14. Box and whisper plots to visually demonstrate variances in knowledge of chronic pain and it's management.<ref name=":9" />

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Education of undergraduate students box plot3.png]]<br>

| |

| | |

| <br>

| |

| | |

| ===== Postgraduate training =====

| |

| | |

| Despite the lack of pre-qualifying training, health professionals are expected to subjectively flag up maladaptive pain behaviours and teach coping strategies. Neuroscience education is currently perceived as a speciality and is delivered as a post graduate masters degree or PhD. However in recent years, delivery of pain neuroscience courses provided by private organisations have become available. These courses are taught by clinical specialists and provided by organisations such as Physio Uk’s Know Pain course, advertised recently on the [http://www.csp.org.uk/events/know-pain-practical-guide-therapeutic-neuroscience-education CSP website]. This is a 2 day workshop open to anyone supportinga chronic pain patient, with a programme including:

| |

| | |

| *How to apply teaching skills within a practice setting

| |

| *The Neurology of Pain

| |

| *Facilitating Pain Education

| |

| *The Language of Pain

| |

| *Pain and the affected mind

| |

| *Getting Going Again

| |

| *Case Studies<br>

| |

| | |

| The course tutor, Mike Stewart (MCSP) is a Clinical Specialist Physiotherapist and explains his journey to becoming a specialist in chronic pain within his [http://physiouk.s3.amazonaws.com/Mike%20Stewart_Know%20Pain_Interview.mp3?inf_contact_key=f652f9d7e9bb1e1e7769a05d4cce3545ada22cb05afed3dc0bbf3a3f95e585cd podcast]. <br>

| |

| | |

| Another course provider the Neuro Orthopaedic Institute (NOI) solely teach health professionals in their ‘Explain pain’ programme, with aim to: <br>

| |

| | |

| *Expand the clinical framework of rehabilitation via the paradigms of neuromatrix and pain mechanisms.

| |

| *Teach biologically based pain management skills under a framework of the sciences of clinical reasoning and evidence from clinical trials, neurobiology and education research.

| |

| *Reconceptualise pain in terms of modern neuroscience and philosophy.

| |

| *Stimulate an urgent reappraisal of current thinking in rehabilitation, with benefits for all stakeholders in clinical outcomes - the patient, the therapist, the referrer and the payer.

| |

| *Teach the core pain management skills of neuroscience education.

| |

| | |

| As has been discussed above, there is inter-professional variability in delivery of undergraduate chronic pain education. Additionally, there is variability in structure and content of neuroscience education courses.<br>

| |

| | |

| ==== Critical appraisal of the evidence: ====

| |

| | |

| Paper 1:'''The Effect of Neuroscience Education on Pain, Disability, Anxiety, and Stress in Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain'''<ref>Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2011; 92(12):2041-2056.</ref><br>

| |

| | |

| A recent systematic review investigating the benefits of pain neuroscience education (PNE), discovered that PNE significantly decreased pain, pain catastrophization and perceived disability compared to the control group (ongoing medical care), in both the short and long-term. Although the review searched all major databases, only 8 studies were included in the review, with all included studies having either good, very good or excellent methodological quality. Nevertheless results from the review failed to discover the most effective frequency and duration of PNE sessions, with RCT’s reporting sessions lasting for 30minutes to 4 hours, with no consensus to the number of required sessions. Moreover the review considered all types of chronic musculoskeletal pain including: Whiplash, Chronic Fatigue syndrome, widespread pain and Chronic Low Back Pain (LBP), thus may lack the generalisability to the treatment of LBP.<br>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Becky mead table of evidence.png]]<br>

| |

| | |

| Paper 2: '''Preoperative Pain Neuroscience Education for Lumbar Radiculopathy'''<ref name=":6" />

| |

| | |

| Compared to the previous systematic review’s poor generalisability of PNE for a range of chronic pain conditions, researchers in this multi-centred randomised control trial focused solely on preoperative PNE for lumbar radiculopathy.

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Louw et al., 2014 table 1.jpg|center]]

| |

| | |

| The internal validity of the study is positive with measures in place to reduce risk of bias where possible. Methodological quality could have only improved through blinding but is not appropriate for the groups. Sample size powered. The study scored a Pedro scale of 8/11. The secondary outcomes improving patient experiences after surgery and health utilisation are hugely clinically relevant, especially in relation to the financial challenges of National Health Service (NHS) in the UK. Any reduction in services post-surgery and thus reducing costs, whilst additionally improving patient experiences with minimal cost to implement cannot be overlooked.

| |

| | |

| However, the UK’s NHS and health insurance systems in the US will differ dramatically in relation to resources available and how often treatments can be accessed. Subsequently, this study did not control the amount of rehabilitation patients were allowed to access, which could further skew results of outcomes, especially compared to the UK where amount of rehabilitation will be determined by post-operative protocol. Finally, the generalisability of the findings to another type of surgery, e.g. spinal fusion, or a patient with non-specific low back pain must be applied with caution despite promising outcomes due to the specificity of the results to surgery for radiculopathy.

| |

| | |

| Paper 3: '''Pain neurophysiology education for the management of individuals with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis''''

| |

| | |

| With regard to the concerns of generalising the results from the previous RCT to non-specific low back pain patients, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Clarke, Ryan and Martin<ref name=":4" />, investigated the impact of PNE, specifically on that management of patients with chronic low back pain. <br>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:SR on PNE 1.jpg|center]]<br>The limitations of this review, as critically appraised using the JBI checklist, were the small number of studies included in the review and furthermore, both studies included were published by one of the co-authors of the PNE manual, so there is a potential conflict of interest. There also could have been a wider range of resources used to search for studies as only 3 databases were observed. <br>

| |

| | |

| However, the critical appraisal of the papers selected was independently assessed by 2 reviewers, minimising bias and each RCT was assessed using the Cochrane back review group (CBRG) guidelines.Contrary to the previous systematic review by Louw and Butler 2011 which focused on a range of chronic conditions, this review is specific to CLBP which make it more generalizable. Lastly the implications for practice and research were based primarily on the reported data.

| |

| | |

| Paper 4:'''Use of therapeutic neuroscience education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report'''<ref name=":7" />

| |

| | |

| <br>

| |

| | |

| Despite some research being done for chronic pain, scant evidence exists in PNE as a treatment in acute pain as a method of preventing chronic pain. This case study attempts to address this issue to guide the way for further research.

| |

| | |

| [[Image:PNE data extraction table Lynette. pic2.png|center]]

| |

| | |

| Although case reports aren’t generalisable or robust they do provide a unique opportunity to present pilot evidence to inform the direction of RCT’s, reviews and guidelines. As a case report the limitations are that use of controls are not a necessity, thus the outcomes for this patient may purely be spontaneous recovery, furthermore other Rx provided in addition to PNE may be credited.<br>

| |

| | |

| ==== Clinical bottom line: ====

| |

| | |

| Due to the limited numbers of studies, study specificity and relatively poor level of methodological quality; currently it is difficult to draw solid conclusions to the specific clinical benefits of PNE for reducing LBP, perceived disability and function.<br>

| |

| | |

| ==== Summary of current concepts of PNE ====

| |

| | |

| *Pain neuroscience education is a 21st century concept that is based on the biophyscosocial model of pain that aims to reconceptualise how patient's percieve their pain.<br>

| |

| *The belief is that the likelihood of chronic pain may not by caused by unhealthy tissue but brain plasticity leading to central sensitisation.

| |

| *PNE consists of educational sessions for patients describing in detail the neurophysiology of pain and pain processing by the nervous system.<br>

| |

| *Evidence on PNE for chronic and acute low back pain shows promising improvements in pain catastrophizing, perceived disability and short term pain relief.

| |

| *However, the research is immature at this stage as there are few studies available and not of a high enough methodological quality to give recommendations for clinical practice.

| |

| | |

| ==== Resources: ====

| |

| | |

| 1) <u>'''Podcast - Chews health podcast SESSION 4 – KNOW PAIN: METAPHORIC EXPRESSION WITH MIKE STEWART –'''</u>[http://chewshealth.co.uk/tpmpsession4/ PART 1], [http://chewshealth.co.uk/tpmpsession5/ PART 2]

| |

| | |

| 2) <u>'''Educational course - Know Pain course: A Practical guide for Therapeutic Neuroscience Education, course provider'''</u>[http://physiouk.s3.amazonaws.com/Mike%20Stewart_Know%20Pain_Interview.mp3?inf_contact_key=f652f9d7e9bb1e1e7769a05d4cce3545ada22cb05afed3dc0bbf3a3f95e585cd discussion]

| |

| | |

| 3) '''<u>Youtube video</u>''' - Lorimer Moseley Pain - How to Explain Pain to Patients, click here:[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIsF8CXouk8 video]

| |

| | |

| 4) <u>'''Professional Forum'''</u>'''- '''iCSP forum discussion on clinicans views of using PNE. CSP Membership required, click here: [http://www.csp.org.uk/icsp/topics/neuroscience-based-pain-education-resounding-success-or-damp-squib www.csp.org.uk/icsp/topics/neuroscience-based-pain-education-resounding-success-or-damp-squib]

| |

| | |

| 5) <u>'''Educational Course Leaflet'''</u> - Know Pain course: A Practical guide for Therapeutic Neuroscience Education, course provider [http://www.physiouk.co.uk/course_pdfs/MikeS_Know_Pain_Transcript.pdf?inf_contact_key=ce65762746464ffc93c7afb89146987b5938f00a5ee899cc899e1bef4f1da23c discussion (transcription)] Explain Pain – [http://www.paintoolkit.org/downloads/epptkd.pdf Patient Leaflet]

| |

| | |

| 6) <u>'''Book'''</u> - Why Do I Hurt? Adriaan Louw (Available online)<br> <br>

| |

| | |

| === References ===

| |

| <references />

| |

| Ali, N. and Thomson, D. (2009). A comparison of the knowledge of chronic pain and its management between final year physiotherapy and medical students. European Journal of Pain, 13(1), pp.38-50.

| |

| | |

| Balagué F, Mannion AF, Pellisé F, Cedraschi C. (2012). Non-specific low back pain. The Lancet. 4 (379), 482-91.<br>

| |

| | |

| Beecher HK. (1956). The frequency of pain severe enough to require a narcotic was studied in 150 male civilian patients and contrasted with similar data from a study of wartime casualties. Efforts were made to have the. Journal of the American Medical Association. 161 (17), 1609-13.<br>

| |

| | |

| Bhattacharyya T, Gale D, Dewire P, Totterman S, Gale ME, McLaughlin S, Einhorn TA, Felson DT. (2003). The clinical importance of meniscal tears demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging in osteoarthritis of the knee. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American volume. 85-A (1), 4-9.<br>

| |

| | |

| Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. (1990). Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation.. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American volume. 72 (3), 403-8.

| |

| | |

| Casey, K.L., Morrow, T.J., Lorenz, J. and Minoshima, S., 2001. Temporal and spatial dynamics of human forebrain activity during heat pain: analysis by positron emission tomography. Journal of Neurophysiology, 85(2), pp.951-959.

| |

| | |

| Clarke, C.L., Ryan, C.G. and Martin, D.J., (2011). Pain neurophysiology education for the management of individuals with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Manual therapy, 16(6), pp.544-549.<br>

| |

| | |

| Cole, L.J., Farrell, M.J., Duff, E.P., Barber, J.B., Egan, G.F. and Gibson, S.J. (2006). Pain sensitivity and fMRI pain-related brain activity in Alzheimer's disease. Brain, 129(11), pp.2957-2965.

| |

| | |

| Goldberg JS. (2008). Revisiting the Cartesian model of pain. Medical Hypotheses. 70 (5), 1029–1033.<br>

| |

| | |

| Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, York J, Das A, McAuley JH. (2008). Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ. 337 (a171).<br>

| |

| | |

| Jordan KP, Kadam UT, Hayward R, Porcheret M, Young C, Croft P. (2010). Annual consultation prevalence of regional musculoskeletal problems in primary care: an observational study. BMC Musculoskeletal disorders. 11 (144).

| |

| | |

| Keller T and Krames ES. (2009). “On the Shoulders of Giants”: A History of the Understandings of Pain, Leading to the Understandings of Neuromodulation. Neuromodulation. 12 (2), 77-84.<br>

| |

| | |

| Kooijmana CM, Dijkstraa PU, Geertzena JHB, Elzingad A, van der Schansa CP. (2000). Phantom pain and phantom sensations in upper limb amputees: an epidemiological study. Pain. 87 (1), 33–41.<br>

| |

| | |

| Linton SJ. (2005). Models of pain perception. Understanding Pain for Better Clinical Practice: A Psychological Perspective. Elsevier . 9-18.<br>

| |

| | |

| Louw A, Louw Q & Crous LC. (2009). Preoperative education for lumbar surgery for radiculopathy. South African Journal of Physiotherapy, 65(2), 3-8.

| |

| | |

| Louw, A., Diener, I., Butler, D.S. and Puentedura, E.J., (2011). The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 92(12), pp.2041-2056.<br>

| |

| | |

| Louw A. (2014). Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching People About Pain. Available: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education. Last accessed 6th Janurary 2016. <br>

| |

| | |

| Louw, A., Diener, I., Landers, M.R. and Puentedura, E.J., (2014). Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine, 39(18), pp.1449-1457.<br>

| |

| | |

| Lower-back-pain-toolkit.com (2015) decartes [image online] Available from: http://www.lower-back-pain-toolkit.com/image-files/descartes. Last accessed 17/01/2016

| |

| | |

| McAllister MJ. (2012). Central Sensitization. Available: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/understanding-chronic-pain/what-is-chronic-pain/central-sensitization. Last accessed 16th January 2016.

| |

| | |

| Melzack R, Wall PD & Ty TC. (1982). Acute pain in an emergency clinic: latency of onset and descriptor patterns related to different injuries..Pain. 14 (1), 33-43. .<br>

| |

| | |

| Moseley, G.L., (2003). Joining forces–combining cognition-targeted motor control training with group or individual pain physiology education: a successful treatment for chronic low back pain. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 11(2), pp.88-94. .<br>

| |

| | |

| Moseley, G.L., (2004). Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. European Journal of Pain, 8(1), pp.39-45. .<br>

| |

| | |

| Moseley, G.L., (2005). Widespread brain activity during an abdominal task markedly reduced after pain physiology education: fMRI evaluation of a single patient with chronic low back pain. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 51(1), pp.49-52..<br>

| |

| | |

| Moseley, G.L. and Butler, D.S., (2015). Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. The Journal of Pain, 16(9), pp.807-813.

| |

| | |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2015). Back pain - low (without radiculopathy). Clinical Knowledge Summary. London: NICE.<br>

| |

| | |

| Nijs, J., Girbés, E.L., Lundberg, M., Malfliet, A. and Sterling, M. (2015). Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Manual therapy, 20 (1), pp. 216-220.

| |

| | |

| Schaible, H.G. and Richter, F., (2004). Pathophysiology of pain. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery, 389(4), pp.237-243.

| |

| | |

| Sharma, N.K., Brooks, W.M., Popescu, A.E., VanDillen, L., George, S.Z., McCarson, K.E., Gajewski, B.J., Gorman, P. and Cirstea, C.M., (2012). Neurochemical analysis of primary motor cortex in chronic low back pain. Brain sciences, 2(3), pp.319-331.

| |

| | |

| Woolf, C.J., (2011). Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain, 152(3), pp.2-15.<br>

| |

| | |

| Zimney, K., Louw, A. and Puentedura, E.J. (2014). Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report. Physiotherapy theory and practice, 30(3), pp.202-209.

| |

| | |

| [[Category:Low_Back_Pain]]

| |

| [[Category:Neurology]] | |

| [[Category:Pain]] | |

| [[Category:Nottingham_University_Project]]

| |