Pain Mechanisms

Original Editor - Tiara Mardosas

Top Contributors - Tiara Mardosas, Carin Hunter, Jess Bell, George Prudden, Admin, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Carina Therese Magtibay, Scott Buxton, Naomi O'Reilly, Venus Pagare and Tarina van der Stockt

Pain: General Overview[edit | edit source]

The most widely accepted and current definition of pain, established by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), is:

"An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage."[1]

Although several theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain the physiological basis of pain, not one theory has been able to exclusively incorporate the entirety of all the aspects of pain perception. The four most influential theories of pain perception include Specificity, Intensity, Pattern and Gate Control theories of pain.[2] However, in 1968, Melzack and Casey described pain as multi-dimensional, where the dimensions are not independent, but rather interactive[3]. The dimensions include sensory-discriminative, affective-motivational and cognitive-evaluate components.

Pain Mechanisms[edit | edit source]

Determining the most plausible pain mechanism(s) is crucial during clinical assessments as this can serve as a guide to determine the most appropriate treatment(s) for a patient[4]. Therefore, criteria upon which clinicians may base their decisions for appropriate classifications have been established through an expert consensus-derived list of clinical indicators. The tables below were adapted from Smart et al. (2010) that classified pain mechanisms as 'nociceptive', 'peripheral neuropathic' and 'central' and outlined both subjective and objective clinical indicators for each. Therefore, these tables serve as an adjunct to any current knowledge and provide as an outline that may guide clinical decision-making when determining the most appropriate mechanism(s) of pain.[5]

When deciding which condition ticks all your boxes of symptoms, please remember Hickam’s dictum[6] - A patient can have multiple coincident unrelated disorders. This can be loosely interpreted as: People can have as many problems as they’d like.

- Multiple pain mechanisms as well as psychological and social factors may be involved at one time. The treatment focus should be on the dominating mechanism as well as any recovery limiting psychological or social factors.

- Pain mechanisms and psychological and social factors can alter and shift with time.

- Pain is based on the patient’s brain perception of threat. Often the threat is real and sometimes it is not. Being better understanding pain mechanisms will help you determine when the threat is real.

Furthermore, being cognisant about the factors that may alter pain and pain perception may assist in determining the most appropriate pain mechanism for a patient. The following are risk factors that may alter pain and pain perception[7]:

- Biomedical

- Psychosocial or Behavioural

- Social and Economical

- Professional/ Work-related

1. Nociceptive Pain Mechanism[edit | edit source]

Nociception is classified as:

A "pathological process in peripheral organs and tissues. Pain projection into damaged body part or referred pain."[8]

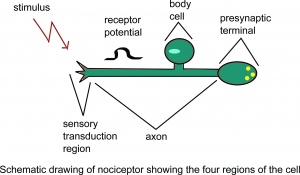

Nociception is a subcategory of somatosensation. Nociception is the neural processes of encoding and processing noxious stimuli.[9] Nociception refers to a signal arriving at the central nervous system as a result of the stimulation of specialised sensory receptors in the peripheral nervous system called nociceptors. Nociceptors are activated by potentially noxious stimuli, as such nociception is the physiological process by which body tissues are protected from damage. Nociception is important for the "fight or flight response" of the body and protects us from harm in our surrounding environment.

Nociceptors can be activated by three types of stimulus within the target tissue - temperature (thermal), mechanical (e.g stretch/strain) and chemical (e.g. pH change as a result of local inflammatory process). Thus, a noxious stimulus can be categorised into one of these three groups. Nociceptive pain is associated with the activation of peripheral receptive terminals of primary afferent neurons in response to noxious chemical (inflammatory), mechanical or ischemic stimuli.[5][10]

The terms nociception and pain should not be used synonymously, because each can occur without the other. Pain arising from activation of the nociceptors is called nociceptive pain. Nociceptive pain can be classified according to the tissue in which the nociceptor activation occurred: superficial somatic ( e.g. skin), deep somatic (e.g. ligaments/tendons/bones/muscles) or visceral ( internal organs).

For more information please see: Nociception

Subjective[edit | edit source]

- Clear, proportionate mechanical/anatomical nature to aggravating and easing factors

- Pain associated with and in proportion to trauma, or pathological process (inflammatory nociceptive), or movement/postural dysfunction (ischemic nociceptive)

- Pain localized to area of injury/dysfunction (with/without some somatic referral)

- Usually rapid resolving or resolving in accordance with expected tissue healing/pathology recovery times

- Responsive to simply NSAIDs/analgesics

- Usually intermittent and sharp with movement/mechanical provocation; may be more constant dull ache or throb at rest

- Pain in association with other symptoms of inflammation (i.e., swelling, redness, heat) (inflammatory nociceptive)

- Absence of neurological symptoms

- Pain of recent onset

- Clear diurnal or 24h pattern to symptoms (i.e., morning stiffness)

- Absence of or non-significantly associated with mal-adaptive psychosocial factors (i.e., negative emotions, poor self-efficacy)

Objective[edit | edit source]

- Clear, consistent and proportionate mechanical/anatomical pattern of pain reproduction on movement/mechanical testing of target tissues

- Localized pain on palpation

- Absence of or expected/proportionate findings of (primary and/or secondary) hyperalgesia and/or allodynia

- Antalgic (i.e., pain relieving) postures/movement patterns

- Presence of other cardinal signs of inflammation (swelling, redness, heat)

- Absence of neurological signs; negative neurodynamic tests (i.e., SLR, Brachial plexus tension test, Tinel’s)

- Absence of maladaptive pain behaviour

2. Neuropathic Pain Mechanism[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (2011) defines neuropathic pain as

"Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system." [11]

It can result from damage anywhere along the neuraxis: peripheral nervous system, spinal or supraspinal nervous system.

- Central neuropathic pain is defined as ‘pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central somatosensory nervous system’.

- Peripheral neuropathic pain is defined as ‘pain caused by a lesion or disease of the peripheral somatosensory nervous system’.

Neuropathic pain is very challenging to manage because of the heterogeneity of its aetiologies, symptoms and underlying mechanisms.

Peripheral neuropathic pain is initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and involves numerous pathophysiological mechanisms associated with altered nerve functioning and responsiveness. Mechanisms include hyperexcitability and abnormal impulse generation and mechanical, thermal and chemical sensitivity.[5][12]

For more information please see: Neuropathic Pain

Subjective[edit | edit source]

- Pain described as burning, shooting, sharp, aching or electric-shock-like[13]

- History of nerve injury, pathology or mechanical compromise

- Pain in association with other neurological symptoms (i.e., pins and needles, numbness, weakness)

- Pain referred in dermatomal or cutaneous distribution

- Less responsive to simple NSAIDs/analgesics and/or more responsive to anti-epileptic (i.e., Neurontin, Lyrica) or anti-depressant (i.e., Amitriptyline) medication

- Pain of high severity and irritability (i.e., easily provoked, taking longer to settle)

- Mechanical pattern to aggravating and easing factors involving activities/postures associated with movement, loading or compression of neural tissue

- Pain in association with other dysesthesias (i.e., crawling, electrical, heaviness)

- Reports of spontaneous (i.e., stimulus-independent) pain and/or paroxysmal pain (i.e., sudden recurrences and intensification of pain

- Latent pain in response to movement/mechanical stresses

- Pain worse at night and associated with sleep disturbance

- Pain associated with psychological affect (i.e., distress, mood disturbances)

Objective[edit | edit source]

- Pain/symptom provocation with mechanical/movement tests (i.e., active/passive, neurodynamic) that move/load/compress neural tissue

- Pain/symptom provocation on palpation of relevant neural tissues

- Positive neurological findings (including altered reflexes, sensation and muscle power in a dermatomal/myotomal or cutaneous nerve distribution)

- Antalgic posturing of the affected limb/body part

- Positive findings of hyperalgesia (primary or secondary) and/or allodynia and/or hyperpathia within the distribution of pain

- Latent pain in response to movement/mechanical testing

- Clinical investigations supportive of a peripheral neuropathic source (i.e., MRI, CT, nerve conduction tests)

- Signs of autonomic dysfunction (i.e., trophic changes)

Note: Supportive clinical investigations (i.e., MRI) may not be necessary in order for clinicians to classify pain as predominantly “peripheral neuropathic”

3. Nociplastic Pain Mechanism[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (2011) defines nociplastic pain as:

“Pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain”[14]

Subjective[edit | edit source]

- Disproportionate, non-mechanical, unpredictable pattern of pain provocation in response to multiple/non-specific aggravating/easing factors

- Pain persisting beyond expected tissue healing/pathology recovery times

- Pain disproportionate to nature and extent of injury or pathology

- Widespread, non-anatomical distribution of pain

- History of failed interventions (medical/surgical/therapeutic)

- Strong association with maladaptive psychosocial factors (i.e., negative emotions, poor self-efficacy, maladaptive beliefs and pain behaviours altered by family/work/social life, medical conflict)

- Unresponsive to NSAIDs and/or more responsive to anti-epileptic or anti-depressant medication

- Reports of spontaneous (i.e., stimulus-independent) pain and/or paroxysmal pain (i.e., sudden recurrences and intensification of pain)

- Pain in association with high levels of functional disability

- More constant/unremitting pain

- Night pain/disturbed sleep

- Pain in association with other dysesthesias (i.e., burning, coldness, crawling)

- Pain of high severity and irritability (i.e., easily provoked, taking long time to settle)

- Latent pain in response to movement/mechanical stresses, ADLs

- Pain in association with symptoms of autonomic nervous system dysfunction (skin discolouration, excessive sweating, trophic changes)

- Often a history of CNS disorder/lesion (i.e., SCI)

Objective[edit | edit source]

- Disproportionate, inconsistent, non-mechanical/non-anatomical pattern of pain provocation in response to movement/mechanical testing

- Positive findings of hyperalgesia (primary, secondary) and/or allodynia and/or hyperpathia within distribution of pain

- Diffuse/non-anatomic areas of pain/tenderness on palpation

- Positive identification of various psychosocial factors (i.e., catastrophisation, fear-avoidance behaviour, distress)

- Absence of signs of tissue injury/pathology

- Latent pain in response to movement/mechanical testing

- Disuse atrophy of muscles

- Signs of autonomic nervous system dysfunction (i.e., skin discolouration, sweating)

- Antalgic (i.e., pain relieving) postures/movement patterns

Central Pain Mechanism[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (2011) defines Central Sensitisation as:

"an increased responsiveness of nociceptors in the central nervous system to either normal or sub-threshold afferent input resulting in: Hypersensitivity to stimuli."[14]

This type of pain does not respond to most medicines and usually requires a tailored program of care that involves addressing factors that can contribute to ongoing pain (lifestyle, mood, activity, work, social factors)

This pain is initiated or caused by a primary lesion or dysfunction in the central nervous system (CNS).[5][15]

The pain can often be defined as an increased responsiveness of nociceptors in the central nervous system to either normal or sub-threshold afferent input[16] resulting in:

- Hypersensitivity to stimuli.[17]

- Responsiveness to non-noxious stimuli.[11][18]

- Increased pain response evoked by stimuli outside the area of injury, an expanded receptive field.[19]

Watch the 2 minute video below on central sensitisation

For more information please see: Central Sensitisation

Practical Applications[edit | edit source]

Once you have an understanding of the process of diagnosing and classifying people in pain, it can often be challenging to bring all the information you have learnt together and understand how it all correlates. Differential diagnosis is difficult as we do not just deal with organic problems. Diagnosis is much easier when we can clearly point to pathoanatomy that causes the symptoms. An example of a clear pathoanatomical diagnosis is an acute, traumatic mechanism of injury, such as a fracture or a torn ligament or tendon. Diagnosis is more challenging but often manageable when it is a common clinical presentation such as frozen shoulder or hip osteoarthritis. It becomes difficult to define when there is no specific pathoanatomic or capsular pattern. This is where classification systems are so essential. Most medical professionals are educated on the biopsychosocial model. Using this model requires assessments of two separate areas to see the full picture of the person. The biomedical path and the psychological and social path.

The Biomedical Path[edit | edit source]

Initially, try to determine if the pain is centrally mediated, peripherally mediated or both. Remember that most centrally mediated pain also has a peripherally mediated component. There are multiple centrally related mechanisms and ways to classify these some examples are: Central sensitization, Central Nervous System Injury (Spinal cord injury, stroke, myelopathy) and Central regional pain syndrome. When considering peripherally mediated pain, first identify if there is a pathoanatomical diagnosis. You should try to have multiple hypotheses of pathoanatomical diagnoses at this step and use your examination and reasoning to determine the likelihood of the hypothesized pathoanatomic driver of their pain being correct. The pathoanatomical diagnoses often indicates the prognosis.

Next, try to classify the pain as being either nociceptive or neurogenic. People can have more than one type of symptom. This step of classification drives the treatment choices. A condition such as radicular pain may have nociceptive pain in the spine as well as neurogenic pain in the periphery.

Nociceptive

Nociceptive pain should be classified using the MDT classification system as well as a tissue based classification system. MDT classification systems overview Dysfunction syndrome- tight, weak contractile, articular, and neural tissue need remodeling to desensitize the ischemic pain mechanism. With this syndrome, the exercise prescription is tissue dominant. Postural syndrome- This is the person that only has pain when sustaining a position for a long time and doesn’t have pain when they get out of that position. This also includes the person that just requires improved motor control.) Derangement Syndrome This is the patient that you can hit home runs with. The McKenzie institute describes this as pain “caused by a disturbance in the normal resting position of the affected joint surfaces”. Hopefully it is a reducible derangement and repeated motions are helpful. If it is an irreducible derangement then waiting for the pathoanatomy to heal or surgery may be required. Other This is reserved for diagnoses that can not be improved with mechanical interventions. Cauda equina syndrome is one that sticks out here. For this category, non-mechanical interventions are required. Summary of MDT overview: For treatment purposes we focus on dysfunction and derangement. Dysfunction has a slower prognosis and derangement a quicker prognosis. People with dysfunction syndrome often require significant tissue based treatment. Sometimes these people love you quickly by treating a muscular pain with a soft-tissue technique, but they require significant amount of treatment to remodel the tissues. People with derangements are the ones we can hit home runs with. (Remember, pathoanatomy determines prognosis so the duration of the improvement and how quickly they can return to full function is determined by the pathoanatomy. The pathoanatomy may need to just go through the phases of healing.) A sufficient repeated movement exam is required when it’s unclear if it’s a dysfunction or derangement. If the problem is due to derangement, then repeated movement should improve symptoms and ROM. If it’s dysfunction, then the ROM will not improve in session. There could be both patterns in a joint like the shoulder. Derangement of the joint and dysfunction of the tendon. Postural problems require identifying that a certain posture should be improved or solely requiring motor control improvement. This person requires coaching instead of treatment for postural positions and training for motor control (i.e. pelvic floor coordination). Others require management instead of treatment. Tissue-based classification system It is essential to know whether pain is inflammatory or ischemic in nature. Inflammatory is broken down into chemical inflammatory and mechanical inflammatory. Both involve chemicals, but chemical inflammatory pain is pain that is constant and mechanical inflammatory pain is intermittent and related to a specific movement. Ischemic pain is pain that worsens with enough activity and should be consistent. Think about peripheral arterial disease. A hallmark of this pain is that it comes on at the same distance of walking each time. This is ischemic pain. This type of pain occurs in multiple tissues in the body. Diurnal pain pattern- worse in the morning, better with activity, but then worsens again and is painful at night. This is due to chemical inflammatory pain. Related reading: Hu, Sally, et al. "A scoping review of the diurnal variation in the intensity of neuropathic pain." Pain Medicine 23.5 (2022): 991-1005. With each visit, clinicians need to assess the patients’ 24-hour pattern. If it’s better in the morning and worsens with activity, but better when they lie down then ischemia is the dominating pain factor. If pain is worse in the morning, but better with activity, but then worsens towards the end of the day then it’s inflammatory. Inflammatory pain will also be present after the activity is done while resting or during the night. This is a diurnal pain pattern. This is the opposite pattern of ischemic pain. If pain changes from intermittent to constant (in exam or otherwise) then pain changed to a chemical inflammatory response. Previously it could have been ischemic. If treatment or activity is overdone then it can turn into a chemical inflammatory pain. If we look at how this fits with the MDT classification it could be any of the classifications that was either treated too aggressively or activity moved it to another pain classification. It would still have the same MDT classification.

Peripheral Neurogenic (Central and Peripheral)

Peripheral neurogenic pain mechanism (PNPM) concerns the peripheral nerve originating outside the dorsal horn all the way to the terminal cutaneous branches. As with nociceptive pain we will classify these using MDT classifications as well as tissue-based classification. MDT classification system guides the type of treatment that is needed. If symptoms simply come on with certain sustained postures then changing postures is the obvious solution. If repeated spine motions can peripheralize or centralize symptoms then derangement is the classification and is the obvious solution. If the pain is not modified by either changing posture or using repeated spine motions then dysfunction is the category. Dysfunction then requires us to identify if the neurogenic pain is neural-dependent or container-dependent. Neural-dependent problems: neural tissue dysfunction and intraneural mechanical problems requiring treatment to the nerve Container-dependent problems: neural tissue interface irritation, entrapment, compression site, and extraneural mechanical problems requiring treatment to the container that is the culprit Once we have appropriately classified the pain using the MDT classification you must classify it using the tissue-based system. Chemical inflammatory neurogenic pain is constant, but can fluctuate intensity. Ischemic and mechanical inflammatory neurogenic pain is absent sometimes. If pain is constant then it is chemical inflammatory. If it is painful quickly with a single movement then it is mechanical inflammatory. If it is painful after a little more time of aggravating movement then it is ischemic. Admittedly, it can be difficult to determine sometimes whether pain is mechanical inflammatory or ischemic. Further, nerves can have features of inflammatory pain and ischemic pain simultaneously. This can happen if the presentation is ischemic, but then it is either treated too aggressively or the patient performs an activity that is too aggressive and then it is inflammatory. This doesn’t mean that ischemic pain is no longer present, but the inflammatory aspect will dominate and once that is reduced then ischemic pain will be dominant again. The key is to treat, assess response, and then modify accordingly. Related reading: Yam, Mun Fei, et al. "General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation." International journal of molecular sciences 19.8 (2018): 2164. Sumizono, Megumi, et al. "Mechanisms of Neuropathic Pain and Pain-Relieving Effects of Exercise Therapy in a Rat Neuropathic Pain Model." Journal of Pain Research 15 (2022): 1925.

The Psychological and Social Path[edit | edit source]

Patients can have recovery limiting factors in the psychological or social realm. These are commonly seen in patients with centrally sensitized pain drivers. There are a wide array of potential factors here, some examples of commonly found scenarios include a lack of sleep, stress, depression, anxiety, adverse childhood events, litigation, family, work status, and nutrition. The key is to be detailed in your examination and consider carefully to what extent these factors are limiting recovery.[20]

Clinical Vignettes[edit | edit source]

The following clinical vignettes are here to supplement the above information and encourage thinking about plausible pain mechanisms.

Case #1: Patient A is a 58-year-old female, retired high school teacher. History of current complaint, approximately 1 month ago, sudden onset of low back pain after starting a season of curling and has been getting worse with walking. Patient A presents with right-sided low back pain (P1) that is a constant dull ache, 7-8/10, and anterior leg pain stopping above the R knee (P2) that is an intermittent ache for ~10-30 minutes rated at 2/10, with an occasional burning pain above the knee. P1 is aggravated by curling with R knee as lead leg, walking >15 minutes, driving >30 minutes and stairs. P2 is aggravated by sitting on hard surfaces >30 minutes and sustained flexion. Coughing and sneezing does not make it worse and P1 is worse at the end of the day. General health is unremarkable. Patient A has had a previous low back injury approximately 10 years ago, underwent treatment and resolved with a good outcome. What is the dominant pain mechanism?

Case #2: Patient B is a 30-year-old male, accountant. History of current complaint is a sudden onset of an inability to turn neck to right and side bend neck to right 2 days ago. On observation, Patient B has head resting in a position of slight L rotation and L side bend. Patient B reports a low level of pain, 2-3/10, only when trying to move head to the R, otherwise movement “is stuck”. Patient B denies any numbness, tingling or burning pain and NSAIDs ineffective. Patient B reported heat and gentle massage to ease any symptoms. Objective findings indicate only right PPIVMs and PPAVMs to have decreased range and blocked. All other cervical spine mobilizations are WNL. What is the dominant pain mechanism?

Case #3: Patient C is a 25-year-old female student. History of current complaint is a MVA 40 days ago while going to school. Patient C was hit from behind, braced and braked with R foot, airbag inflated, checked out of the ER then home on bed rest. Since then, Patient C has had 6 visits of physiotherapy with no improvement and neck pain persisting. P1 is left C2-7 and upper trapezius, rated 3-9/10, and pain varies from a dull ache to sharp pain with occasional pins and needles, depending on neck position. P1 is aggravated by sitting and walking > 30 minutes and turning to the left. P1 occasionally disturbs sleep, particularly when rolling over in bed and coughing/sneezing does not increase pain. P1 is sometimes eased by heat and stretching. NSAIDs have no effect. X-ray day of MVA is negative, negative cauda equina, vertebral artery and cord signs. General health is generally good. Minor sprains and strains in sports, but never required treatment and no previous MVA. Patient C voices concern about fear of driving and has not been driving since the accident. Patient C has also reported an increase in sensitization in her lower extremities. What is the dominant pain mechanism?

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698. [Accessed 19 July 2020]

- ↑ Moayedi M, Davis KD. Theories of pain: From specificity to gate control. J Neurophysiol 2013;109:5-12. (accessed 1 April 2014).

- ↑ Melzack R, Casey KL. Sensory, motivational, and central control determinants of pain: a new conceptual model. The skin senses. 1968 Jan 1;1.

- ↑ Graven-Nielsen, Thomas, and Lars Arendt-Nielsen. "Assessment of mechanisms in localized and widespread musculoskeletal pain." Nature Reviews Rheumatology 6.10 (2010): 599.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, Doody C. Clinical indicators of 'nociceptive', 'peripheral neuropathic' and 'central' mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain. A Delphi survey of expert clinicians. Man Ther 2010;15:80-7. (accessed 1 April 2014).

- ↑ Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Newman NJ, Pomeroy SL. Diagnosis of neurological disease. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. 2022.

- ↑ Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. The lancet. 2006 May 13;367(9522):1618-25.

- ↑ Treede RD. The International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: as valid in 2018 as in 1979, but in need of regularly updated footnotes. Pain reports. 2018 Mar;3(2).

- ↑ Loeser JD, Treede RD. The Kyoto protocol of IASP Basic Pain Terminology. Pain. 2008; 137(3): 473–7. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.025. PMID 18583048

- ↑ Baron R, Binder A, Wasner G. Neuropathic pain: diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology. 2010 Aug 1;9(8):807-19.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 International Association for the Study of Pain. IASP Terminology. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698#Sensitization.

- ↑ Baron R. Peripheral neuropathic pain: from mechanisms to symptoms. The Clinical journal of pain. 2000 Jun;16(2 Suppl):S12-20.

- ↑ Świeboda P, Filip R, Prystupa A, Drozd M. Assessment of pain: types, mechanism and treatment. Pain. 2013;2(7).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Nijs J, Lahousse A, Kapreli E, Bilika P, Saraçoğlu İ, Malfliet A, Coppieters I, De Baets L, Leysen L, Roose E, Clark J. Nociplastic pain criteria or recognition of central sensitization? Pain phenotyping in the past, present and future. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Jul 21;10(15):3203.

- ↑ Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994

- ↑ Louw A, Nijs J, Puentedura EJ. A clinical perspective on a pain neuroscience education approach to manual therapy. J Man Manip Ther. 2017; 25(3): 160-168.

- ↑ Woolf CJ, Latremoliere A. Central Sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. The Journal of Pain 2009; 10(9):895-926

- ↑ Loeser JD, Treede RD. The Kyoto protocol of IASP basic pain terminology. Pain 2008;137: 473–7.

- ↑ Dhal JB, Kehlet H. Postoperative pain and its management. In:McMahon SB, Koltzenburg M, editors. Wall and Melzack's Textbook of pain. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone;2006. p635-51.

- ↑ O’Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O’Keeffe M, Smith A, Dankaerts W, Fersum K, O’Sullivan K. Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Physical therapy. 2018 May 1;98(5):408-23.