Myofascial Pain

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Original Editor - Add a link to your Physiopedia profile here.

Top Contributors - German Garcia, Jo Etherton, Kim Jackson, Oyemi Sillo, Vidya Acharya, Alex Benham, Sai Kripa, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Vanessa Rhule, WikiSysop, Candace Goh, Lauren Lopez and Lucinda hampton

Definition[edit | edit source]

The myofascial pain syndrome is a common clinical problem of muscle pain involving sensory, motor and autonomic symptoms caused by myofascial trigger points. YOU SAY THIS IS A COMMON PROBLEM>>PLEASE CAN YOU REFErCE AND GIVE STATISTICS TO SUBSTATITAE THIS CLAIM.

A myofascial trigger point is defined as a hyperirritable spot, usually within a taut band of skeletal muscle wich is painful on compression and can give rise to characteristic Referred Pain, motor dysfunction and autonomic phenomena.[1]

Classification and Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Myofascial trigger points are classified into active and latent trigger points[1][2]. An active trigger point is one with spontaneous pain or pain in response to movement that can trigger local or referred pain. A latent trigger point is a sensitive spot with pain or discomfort only elicited in response to compression. The myofascial trigger points (active or latent) follow common clinical characteristics such as:

- Pain on compression. This may elicit local pain and/or referred pain that is similar to a patient's usual clinical complaint or may aggravate the existing pain.

- Local twitch response. Snapping palpation (compression across the muscle fibers rapidly) may elicit a local twitch response, which is a quick contraction of the muscle fibers in or around the taut band.

- Muscle tightness. Restricted range of stretch, and increased sensitivity to stretch, of muscle fibers in a taut band may cause tightness of the involved muscle.

- Local myasthenia. The muscle with a trigger point may be weak, but usually no atrophy can be noticed.

- Patients with trigger points may have associated localized autonomic phenomena, including vasoconstriction, pilomotor response and hypersecretion.

When the pain resulting from an active trigger point becomes persistant the patient may develop satellite trigger points. A satellite trigger point is localized in the referral zone of the primary trigger point, usualy in an overloaded synergist muscle[1]. PLEASE CAN YOU EXPLAIN THE TERMs 'REFRERAL ZONE & PRIMARY TRIGGER POINT'

Another interesting clinical characteristic is the spontaneous electrical activity (SEA) recorded in myofascial trigger point sites[3]. The site of this electrical activity is called "active locus". SEA consists of continuous, noise-like action potentials that can range from 5 to 50 µV, with intermittent large amplitude spikes up to 600 µV. This abnormal endplate potential is caused by an excessive release of acetylcholine at the motor endplate. The magnitude of SEA is related to the pain intensity in patients with myofascial trigger points. HOW IS THIS MEASURED< IS IT DETECTABLE IN CLNICAL PRACTCIE?

Etiology[edit | edit source]

THIS SECTION IS A LITTLE CONFUSING. YOU MENTION ON SEVERL OCCASSIONS THERE IS NO AGREED CONCENSUS ON SEVERAL ASECTS OF THE ETIOLOGY..I WOULD LIKE SOME OF THESE TO BE EXPLORED TO GIVE A CRITICAL ELEMENT TO THE ARTICLE.

The taut band is the first sign of the muscular response to biomechanical stress[4]. The taut band formation within a trigger point it is not clear but it may be due, among other causes, to muscle contractures. Prolonged contractures are likely to lead to the formation of latent trigger points, which can eventually evolve into active trigger points.

Myofascial pain can also be caused by low-level muscle contractions which involves a selective overload of the earliest recruited and last derecruited motor units ("Henneman's size principle"[5]). Smaller motor units are recruited before and derecruited after larger ones; as a result, the smaller type I fibers are continuously activated during prolonged motor tasks, wich in turn it can result in metabolically overloaded motor units with a subsequent activation of autogenic destructive processes and muscle pain, this is also known as the Cinderella hypothesis[6][7]. Several other possible mechanisms can lead to the development of trigger points, including[1][4][2] :

- Muscle overload.

- Postural stress.

- Direct trauma.

- Eccentric contractions in unconditioned or unaccustomed muscle

- Maximal or submaximal concentric contractions.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

The initial change in muscle that is associated with myofascial pain seems to be the development of the taut band, which is in term a motor abnormality. Several mechanisms have been hypothesied to explain this motor abnormality, the most accepted one is the "Integrated Hypothesis" first developed by Simmons[1] and later expanded by Gerwin[8].

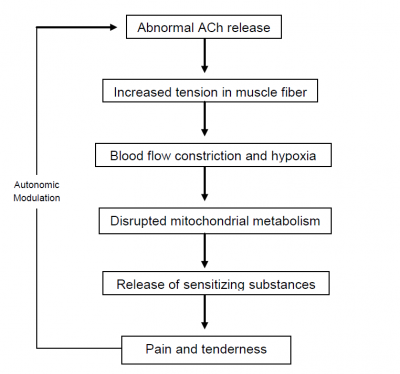

Simmons' integrated hypothesis is a six-link chain that starts with the abnormal release of acetylcholine. This triggers an increase in muscle fiber tension (formation of taut band). The taut band is thought to constrict blood flow that leads to local hypoxia. The reduced oxygen disrupts mitochondrial energy metabolism reducing ATP and leads to tissue distress and the release of sensitizing substances. These sensitizing substances lead to pain by activation of nociceptors and also lead to autonomic modulation that then potentiates the first step: abnormal acetylcholine release.

Gerwin expanded this hypothesis by adding more specific details[8]. He stated that sympathetic nervous system activity augments acetylcholine release and that local hypoperfusion caused by the muscle contraction (taut band) resulted in muscle ischemia or hypoxia leading to an acidification of the pH.

The prolonged ischemia also leads to muscle injury resulting in the release of potassium, bradykinins, cytokines, ATP, and substance P which might stimulate nociceptors in the muscle. The end result is the tenderness and pain observed in myofascial trigger points.

Depolarization of nociceptive neurons causes the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP).

CGRP inhibits acetylcholine esterase, increases the sensitivity of acetylcholine receptors and release of acetylcholine resulting in SEA.

In recent studies Shah et al.[9] confirmed the presence of these substances using microdyalisis techniques at trigger point sites. Elevations of substance P, protons (H+), CGRP, bradykinin, serotonin, norepinephrine, TNF, interleukines, and cytokines were found in active trigger points compared to normal muscle or even latent trigger points. The pH of the active trigger point region was decreased as low as pH 4 (normal pH value is 7,4) causing muscle pain and tenderness as well as a decrease in acetylcholine esterase activity resulting in sustained muscle contractions.

Perpetuating Factors[edit | edit source]

In some cases there may be perpetuating factors that have a feed forward effect on myofascial pain. These factors may chronify the pain and tenderness. Perpetuating factors may also have an important role in wide spreading the referred pain by Central sensitisation mechanisms[1][2][4].

There are mechanical perpetuating factors such as:

- Scoliosis

- Leg length discrepancies

- Joint hypermobility

- Muscle overuse

There are as well systemic or metabolic perpetuating factors such as:

- Hypothyroidism

- Iron insufficiency

- Vitamin D insufficiency

- Vitamin C insuffisency

- Vitamin B12 insufficiency

Psychosocial perpetuating factors:

- Stress

- Anxiety

And other possible perpetuating factors:

- Infectious diseases

- Parasitic diseases (e.g. Lyme disease)

- Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Use of statin-class drugs

In some cases, managing and correcting an identified perpetuating factor may lead to a complete resolution of pain and may be the sole therapeutic approach needed to relief the patient’s symptoms. THIS IS A BIG CLAIM..NEEDS A REFERNCE & EVIDENCING

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Palpation is the gold standard in identifying the presence of taut bands in muscle. This involves the training and accurate skills of practitioners to identify these taut bands.

Palpation of taut bands needs a precise knowledge of muscle anatomy, direction of specific muscle fibres and muscle function.

The palpation on muscle must meet several essential criteria and confirmatory observations to identify the presence of trigger points[1].

Essential criteria:

- Taut band palpable (where muscle is accessible)

- Exquisite spot of tenderness in a taut band

- Patient recognition of current pain complaint by pressure of examiner

- Painful limit to full stretch ROM

Confirmatory observations:

- Visual or tactile local twitch response

- Referred pain sensation on compression of the taut band

- SEA confirmed by electromyography

The interrater and intrarater reliabily of palpation has been a subject of scientific research over the past years.[10][11][12][13] There has been improvement in the methodological quality in recent studies but the main problem rests the lack of rater blinding. It is a problem hard to solve because the reliability of palpation depends on a high expertise level from the examiner.

Recent research has shown interesting results using magnetic resonance elastography.[14] The technique involves the introduction of cyclic waves into the muscle, and then using phase contrast imaging to identify tissue distortions. The speed of the waves is determined from the images. Shear waves travel more rapidly in stiffer tissues. The taut band can then be distinguished from the surrounding normal muscle.

Another recent technique used to confirm the extension of myofascial trigger point sites is sonoelastography combined with Doppler imaging.[15]

It uses a clinical ultrasound imaging system with a 12-5 MHz linear array, associated to an external vibration source (hand held vibrating massager) working at cycles of approximately 92Hz. Doppler imaging is used to identify surrounding blood flows.

Ballyns et al. showed in their study that sonoelastography can be a useful tool to classify myofascial trigger points by area. Larger areas correspond to active trigger points and smaller ones to latent trigger points.

To note that this technique needs preliminary manual palpation of trigger points.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

One source of confusion associated with myofascial pain is fibromyalgia. It is true that both entities are likely to cause severe muscle pain and tenderness but they do not share the same etiology or pathogenesis and their clinical presentation is not the same. Therefore two different conditions should be distinguished.

In 1990 the American College of Rheumatology published the diagnostic and classification criteria for fibromyalgia.[16] This classification has been updated recently in 2010.[17] The diagnosis of fibromyalgia is based on a history of widespread pain (for at least 3 months of duration), defined as bilateral, upper and lower body, as well as spine, and the presence of excessive tenderness on applying pressure to 11 of 18 specific muscle-tendon sites or tender points.

Main differences between myofascial pain and fibromyalgia:

| Myofascial Pain | Fibromyalgia |

| Local Pain | Widespread Pain |

| Regional Condition | Bilateral as well as axial Pain |

| Presence of Taut Band | Absence of taut bands |

| Referred Pain |

Presence of at least 11 tender points |

A differential diagnosis should be made with other conditions such as: muscle spasm, neuropathic or radicular pain, delayed onset muscle pain, articular dysfunction and infectious myositis.

Management[edit | edit source]

There are two different approaches in the treatment of myofascial trigger points. There are non-invasive techniques such as Ultrasound therapy, Low-level laser therapy, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), drug therapy (e.g. myorelaxants) and several physical and manual therapy techniques such as:

- Stretching techniques (e.g. spray and stretch)

- Post-isometric relaxation

- Active Release Techniques

- Trigger point pressure release

- Muscle energy techniques

- Massage

In a recent study, Bron et al.[18] conducted a controlled trial in the treatment of myofascial trigger points in patients with shoulder pain. They decided to only use manual techniques associated with home exercises and ergonomic recommendations. After 12 weeks of treatment there was a statistically significant improvement in the intervention group compared with the control group.

On the other hand there are different invasive techniques that share a common goal: the inactivation of an active loci in a central trigger point with a needle.

Different modalities exist:

- Dry needling

- Anesthetic injections

- Botulin toxin A injection

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Travell JG, SimmonsDG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. 2nd ed. Vol 1. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1999

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Fernández‐de‐las‐Peñas, C., Cuadrado, M. L., Arendt‐Nielsen, L., Simons, D. G., Pareja, J. A. (2007). Myofascial trigger points and sensitization: an updated pain model for tension‐type headache. Cephalalgia, 27(5), 383-393.

- ↑ Hubbard, D. R., Berkoff, G. M. (1993). Myofascial trigger points show spontaneous needle EMG activity. Spine, 18(13), 1803-1807.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gerwin, R. D. (2001). Classification, epidemiology, and natural history of myofascial pain syndrome. Current pain and headache reports, 5(5), 412-420.

- ↑ Enoka, R. M. Stuart, D. G. (1984). Henneman's ‘size principle’: current issues. Trends in neurosciences, 7(7), 226-228.

- ↑ Thorn, S., Forsman, M., Zhang, Q. Taoda, K. (2002). Low-threshold motor unit activity during a 1-h static contraction in the trapezius muscle. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 30(4), 225-236.

- ↑ Kallenberg, L. A., Hermens, H. J. (2006). Motor unit action potential rate and motor unit action potential shape properties in subjects with work-related chronic pain. European journal of applied physiology, 96(2), 203-208.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gerwin, R. D., Dommerholt, J., Shah, J. P. (2004). An expansion of Simons’ integrated hypothesis of trigger point formation. Current pain and headache reports, 8(6), 468-475.

- ↑ Biochemicals Associated With Pain and Inflammation are Elevated in Sites Near to and Remote From Active Myofascial Trigger Points. Shah, Jay P. et al. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Volume 89, Issue 1, 16-23

- ↑ Bron, C., Franssen, J., Wensing, M., Oostendorp, R. A. (2007). Interrater reliability of palpation of myofascial trigger points in three shoulder muscles. Journal of Manual Manipulative Therapy, 15(4), 203-215.

- ↑ Gerwin, R. D., Shannon, S., Hong, C. Z., Hubbard, D., Gevirtz, R. (1997). Interrater reliability in myofascial trigger point examination. Pain, 69(1), 65-73.

- ↑ Lucas, N., Macaskill, P., Irwig, L., Moran, R., Bogduk, N. (2009). Reliability of physical examination for diagnosis of myofascial trigger points: a systematic review of the literature. The Clinical journal of pain, 25(1), 80-89.

- ↑ Lucas, N., Macaskill, P., Irwig, L., Moran, R., Bogduk, N. (2009). Reliability of physical examination for diagnosis of myofascial trigger points: a systematic review of the literature. The Clinical journal of pain, 25(1), 80-89.

- ↑ Chen, Q., Bensamoun, S., Basford, J. R., Thompson, J. M., An, K. N. (2007). Identification and quantification of myofascial taut bands with magnetic resonance elastography. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 88(12), 1658-1661.

- ↑ Ballyns JJ, Shah JP, Hammond J, Gebreab T, Gerber LH, Sikdar S. Objective Sonographic Measures for Characterizing Myofascial Trigger Points Associated With Cervical Pain. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine 2011;30(10):1331-1340.

- ↑ Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160-172

- ↑ Wolfe F, Clauw D, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg D, Katz RS, Mease P, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:600–10

- ↑ Bron et al.: Treatment of myofascial trigger points in patients with chronic shoulder pain: a randomized, controlled trial. BMC Medicine 2011 9:8