Metatarsalgia

Original Editors - David De Meyer

Top Contributors - Diego Zaragoza, Lucinda hampton, Maxim de Clippele, David De Meyer, Evan Thomas, Kim Jackson, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Adam Vallely Farrell, Chrysolite Jyothi Kommu, Jess Bell, 127.0.0.1, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Khloud Shreif and WikiSysop

Definition[edit | edit source]

Metatarsalgia is a general term for pain in the area of the metatarsophalangeal joints.

Most common causes include

- Freiberg disease

- Interdigital nerve pain (Morton neuroma)

- Metatarsophalangeal joint pain

- Sesamoiditis

- Submetatarsal head fat pad atrophy typically associated with aging[2]

Metatarsalgies are often accompanied by excessive callus formation over a bony protrusion, with severe pain and pressure sensitivity around the callus.[3][4]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

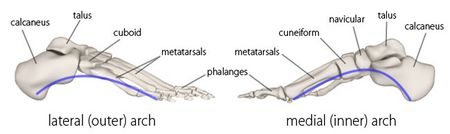

The most important and relevant anatomy is the metatarsals.The metatarsus of the foot consists of five long bones, which are called the metatarsals.

The metatarsals

- Comprised of a proximal base, shaft and distal head.

- Proximally connected to the tarsal bones and distally to the the phalanges.

- Named I to V medially to laterally, from the dorsal surface of the foot.

- Convex on their dorsal surfaces but concave on their plantar surfaces

- Along with the tarsals, help form the arches of the foot, which are essential in both weight bearing and walking.[5]

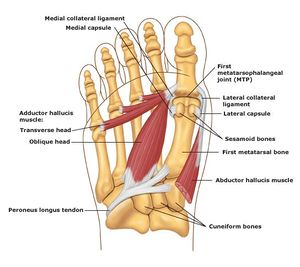

The joints between the head of the metatarsals and the respective proximal phalanx is called the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP).

- These joints form the ball of the foot, and the ability to move in these joints is very important for normal walking.

- In addition, the bases of the metatarsals articulate with each other to form intermetatarsal joints.[5]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Common causes include

- interdigital (Morton) neuroma

- Freiberg infraction

- stress fractures involving the foot

- intermetatarsal bursitis

- adventitial bursitis

- inflammatory and degenerative arthritis

- metatarsophalangeal joint synovitis/capsulitis

- tendinosis/tenosynovitis

- plantar plate disruption / plantar plate tears

- schwannoma[6]

- pes cavus or high arched foot

- excessive pronation of the foot

- clawing or hammer toes

- tight extensor tendons of the toes

- prominent metatarsal heads

- Morton’s foot—there is a shortened first metatarsal, which results in an abnormal subtalar joint, and increased weight going through the second metatarsophalangeal joint.[7]

Causes[edit | edit source]

- There can be multiple causative factors. Often localized to the first metatarsal head .Next most frequent site of metatarsal head pain is under the second metatarsal.[4][8][9]

Factors that can cause excessive pressure are:

- Participating in high impact activities without proper footwear and/or orthotics

- Older age as the pad in the foot tends to thin out making it much more susceptible pressue and pain

- An imbalance in the length of the metatarsals

- Majority seem to be related to foot and ankle deformity

- Disturbances in gait

- Morphology of the foot (e.g. increased bone length that protrudes into the bottom of the foot)

- A shortened Achilles tendon

Subtypes

- Primary metatarsalgia refers to symptoms arising from innate abnormalities in the patient’s anatomy leading to overload of the affected metatarsal. [10]

- Secondairy metatarsalgia can be caused by systemic conditions such as arthritis of the MTP joint.

- Iatrogenic metatarsalgia can occur after (failed) reconstructive surgery.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Metatarsalgia most commonly results from misalignment of the joint surfaces with altered foot biomechanics, may cause

- Joint subluxations,

- Flexor plate tears,

- Increased pain during the mid-stance and propulsion phases of walking as body weight is shifted forward onto the forefoot.[11]

- Capsular impingement

- Joint cartilage destruction (osteoarthrosis).

- Misaligned joints synovial impingement, with minimal if any heat and swelling (osteoarthritic synovitis).

- Metatarsophalangeal joint subluxation - May occur as a result of chronic inflammatory arthropathy, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

- Metatarsophalangeal joint pain - weight bearing and a sense of stiffness in the morning can be significant early signs of early RA.

- Loss of metatarsal fat pad (usually cushions the stress between the metatarsals and interdigital nerves during walking)tends to move distally under the toes, causing interdigital neuralgia/Morton neuroma.

- To compensate for the loss of cushioning, adventitial calluses and bursae may develop.

- Coexisting rheumatoid nodules beneath or near the plantarflexed metatarsal heads may increase pain.

The 2nd metatarsophalangeal joint is most commonly affected.

- Usually, inadequate 1st ray (1st cuneiform and 1st metatarsal) function results from excessive pronation (the foot rolling inward and the hindfoot turning outward or everted), often leading to capsulitis and hammer toe deformities.

- Overactivity of the anterior shin muscles in patients with pes cavus (high arch) and ankle equinus (shortened Achilles tendon that restricts ankle dorsiflexion) deformities tends to cause dorsal joint subluxations with retracted (clawed) digits and retrograde, increased submetatarsal head pressure and pain[2].

Metatarsophalangeal joint pain may also result from functional hallux limitus

- Limits passive and active joint motion at the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint.

- Patients usually have foot pronation disorders that result in elevation of the 1st ray with lowering of the medial longitudinal arch during weight bearing.

- As a result of the 1st ray elevation, the proximal phalanx of the great toe cannot freely extend on the 1st metatarsal head; the result is jamming at the dorsal joint leading to osteoarthritic changes and loss of joint motion (with time, pain may develop).

Another cause of 1st metatarsophalangeal joint pain due to limited motion is direct trauma with stenosis of the flexor hallucis brevis, usually occurring within the tarsal tunnel. If pain is chronic, the joint may become less mobile with an arthrosis (hallux rigidus), which can be debilitating.

Acute arthritis can occur secondary to systemic arthritides such as gout, RA, and spondyloarthropathy.[2]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Mainly clinical evaluation

- Exclusion of infection or arthropathy if signs of inflammation

- To differentiate one diagnosis from another, the use of the patient’s history, physical exam, roentgenograms, cholesterol-crystal force-plate analysis, intra-articular/digital injections and additional laboratory studies (electromyography, arteriograms, venograms,..) can be used.[12]

- Investigations - X-rays can be performed to assess the degree of degeneration of the joint.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Foot Function Index (FFI) - The Brazilian-Portuguese version of the FFI questionnaire was found to be a valid and reliable instrument for foot function evaluation, and can be used both in scientific settings and in clinical practice.[13]

- Foot Posture Index (FP1-6) - No scientific evidence found correlated to metarsalgia[14]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Look for evidence of systemic disease especially:

- diabetic neuropathy

- inflammatory arthropathy

- neurological disease

- vascular disease

Examination must begin proximally:

- any stiffness or deformity (including length discrepancy) which might alter pressures on the forefoot?

- tight Achilles tendon or reduced ankle dorsiflexion, especially if there is fixed equinus (remember to examine in subtalar neutral position)

- pes cavus

• overpronated foot with unstable 1st ray - peripheral neurological examination

- tenderness or a positive Tinel sign over the major nerve trunks

- hallux deformity or painful 1st MTPJ

- hammer or claw toes - if so, how flexible is the MTPJ. With the MTPJ reduced (if possible) is the fat pad reduced under the metatarsal heads?

- interdigital tenderness, palpable swelling or a positive metatarsal head compression test or Mulder's click

- interdigital corns

- tenderness and/or calluses under the metatarsal heads - check the relationship between the relative positions of heads and calluses. Most calluses are relatively diffuse although there may be increased thickening under the MT heads. However, a very localised callus should raise suspicions of a plantar condylar eminence

- metatarsophalangeal instability or irritability

- it is often possible to assess the relative heights and lengths of metatarsals by palpation

- look for scars of previous surgery

Always screen the patient for diabetes - a urine test is usually enough

This will usually indicate one or more possible factors which may be contibuting to forefoot pain. Differential injections around interdigital nerves and into MTP joints may help distinguish between MTP synovitis and interdigital neuralgia (although at least 10% of patients with each of these conditons also has the other) (Miller 2001). In the end it often requires experience-based judgement to decide which factors should be tackled and in what order. [15]

For second metatarsophalangeal joint instability, Dotty and Jesse F. devided the clinical staging of examination findings in 4 grades: [16]

- Grade 0: No MTP joint malalignment; prodromal phase with pain but no deformity

- Physical Examination Findings: MTP joint pain, thickening or swelling of the MTP joint, diminished toe purchase, negative drawer test result.

- Grade 1: Mild malalignment of MTP joint; widening of web space, medial deviation

- Physical Examination Findings: MTP joint pain, swelling of MTP joint, reduced toe purchase, mildly positive drawer test result (<50% subluxated).

- Grade 2: Moderate malalignment; medial, lateral, dorsal, or dorsomedial deformity, hyperextension of MTP joint

- Physical Examination Findings: MTP joint pain, reduced swelling, no toe purchase, moderately positive drawer test (>50% subluxated).

- Grade 3: Severe malalignment; dorsal or dorsomedial deformity; second toe can overlap hallux; might have flexible hammertoe

- Physical Examination Findings: Joint and toe pain, little swelling, no toe purchase (can dislocate MTP joint), flexible hammertoe.

- Physical Examination Findings: Joint and toe pain, little swelling, no toe purchase (can dislocate MTP joint), flexible hammertoe.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Orthotics -

- Foot orthoses with metatarsal pads may help redistribute and relieve pressure from the noninflamed joints.

- With excess subtalar eversion or when the feet are highly arched, an orthotic that corrects these abnormal alignments should be prescribed.

- Shoes with rocker sole modifications may also help.

- For functional hallux limitus, orthosis modifications may further help to plantarflex the 1st ray to improve metatarsophalangeal joint motion and reduce pain.

- If the 1st ray elevation cannot be reduced by these means, an extended 1st ray elevation pad may be helpful.

- For more severe limitation of 1st metatarsophalangeal motion or pain, the use of rigid orthoses, carbon fiber plates, or external shoe bars or rocker soles may be necessary to reduce motion at the joint.[2]

Surgery may be needed if conservative therapies are ineffective. If inflammation (synovitis) is present, injection of a local corticosteroid/anesthetic mixture may be useful.

NSAIDS are most commonly used for the relief of mild to moderate pain. But you have to use the right shoes.[8],

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment is initially non conservative. The pressure on the forefoot can be reduced by stretching exercises to perform at the level of the lower limb, amounting. Also custom-made orthopedic insoles can reduce pressure.

Sometimes, in very specific cases, an infiltration, followed by taping a few weeks, brings some comfort, also some mobilization exercises are recommended.[4]

Gajdosic and coworkers demonstrated that a 6-week stretching program increased the maximal ankle dorsiflexion angle and length extensibility. They further demonstrated that stretching enhances the dynamic passive length and passive resistive properties. [17] - level of evidence 1b.

If these treatments have insufficient impact, surgery may be considered, depending on the defects, causes. In cases of hallux valgus or varus position, it should also be surgically corrected. The most common procedure is an osteotomy, where the metatarsal (one or more) responsible for the excess pressure, is shortenend or lifted. After surgery, one can basically rely on an immediate postoperative specifically designed shoe.[2,4,5]

Distal metatarsal osteotomies (such as The Weil osteotomy) provide a longitudinal decompression and is particularly relevant in patients suffering from metatarsalgia due to an excessively long metatarsal. One problem is the plantar translation of the metatarsal head during shortening. [18] - level of evidence 3a . Based on those results, Maceira and coworkers introduced the so-called “triple-osteotomy”. This modified osteotomy affords precise and accurate shortening of the metatarsal without unwanted plantar translation of the heads. The triple osteotomy also preserves the relationship between the dorsal interossei and transverse axis of rotation of the MTP joint to avoid an extension deformity. [19] - level 4 evidence.

The high pressure under the metatarsal heads can be reduced by applying metatarsal pads. In a double-blind study, tear-drop shaped, polyurethane metatarsal pads were applied by experienced physiatrists to a total of 18 feet. As a result, there were significantly decreased maximal peak pressures and pressure time intervals during exercise that correlated with better pain and function outcomes. [4],8]

Espinosa stated (with 2 clinical studies (level 2A evidence) and 1 retrospective study (level 2B evidence) as reference) that generally, accommodative insoles may redistribute pressure under the foot while functional orthoses are intended to control abnormal intersegmental motion. But both of them may be useful in the non-operative management of metatarsalgia.[20]

Not much scientific literature exists to confirm the effectiveness of these conservative treatment for the treatment of central metatarsalgia. Nevertheless, such measures often meet with success and have the additional benefit of not compromising future treatment [21]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8 (2008) - level of evidence: 1a

Resources[edit | edit source]

- The use of collagen injections in the treatment of metatarsalgia: A Case Report http://www.jfas.org/article/S1067-2516(10)00288-7/abstract

- Sports medicine - metatarsalgia http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/85864-overview

- J. Gregg, P. Marks (2007). Australasian Radiology: Metatarsalgia: An ultrasound perspective. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Pages 493-499.

- Associatie orthopdedie Lier http://www.associatie-orthopedie-lier.be/Generic/servlet/Main.html;jsessionid=B2F5539057DBEF99F23742666B6A844C?p_pageid=37247

- Foot and ankle institute http://voetenenkelinstituut.be/aandoeningen/voorvoet/metatarsalgie/

- Treatment & medication http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/85864-treatment

- Walter R. Frontera, Julie K. Silver, Thomas D. Rizzo (2008). Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Elsevier Health Sciences. Pages 461-475.

- Metatarsalgia - forefoot pain http://www.sportsinjurybulletin.com/archive/metatarsalgia.html

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ https://greenbayacupuncture.co/2017/05/17/metatarsalgia-forefoot-pain/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Mercks manual. MTP joint pain Available from:https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/musculoskeletal-and-connective-tissue-disorders/foot-and-ankle-disorders/metatarsophalangeal-joint-pain (last accessed 25.6.2020)

- ↑ Doty, Jesse F., and Michael J. Coughlin. "Metatarsophalangeal joint instability of the lesser toes." The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 53.4 (2014): 440-445. (level of evidence: 2a)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8 (2008) (level of evidence: 1a

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/metatarsal-bones

- ↑ Radiopedia Metatarsalgia Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/metatarsalgia (last accessed 25.6.2020)

- ↑ Brukner P. Brukner & Khan's clinical sports medicine. North Ryde: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 G. McPoil Thomas and Schuit Dale. “Management of metatarsalgia secondary to biomechanical disorders”. Physical Therapy 66(6): 970-2; July 1986 (level of evidence: 3c)

- ↑ Sobel Ellen, D.P.M., Ph. D., C.PED. and Levitz Steven, D.P.M.; “Metatarsalgia : Diagnosis and Manangement, Etiologies and Differential diagnoses”. Podiatry Management (level of evidence: 5)

- ↑ Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8 (2008)

- ↑ G. McPoil Thomas and Schuit Dale. “Management of metatarsalgia secondary to biomechanical disorders”. Physical Therapy 66(6): 970-2; July 1986

- ↑ J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980 Jul;62(5):723-32. Scranton PE Jr; Metatarsalgia: diagnosis and treatment

- ↑ Martinez, Bruna Reclusa, et al. Validity and reliability of the Foot Function Index (FFI) questionnaire Brazilian-Portuguese version. 2016.

- ↑ Haque, Syed, et al. Outcome of Minimally Invasive Distal Metatarsal Metaphyseal Osteotomy (DMMO) for Lesser Toe Metatarsalgia. Foot & Ankle International. 2015.

- ↑ http://www.foothyperbook.com/elective/metatarsalgia/metatarsalgiaExam.html

- ↑ Doty, Jesse F., and Michael J. Coughlin. "Metatarsophalangeal joint instability of the lesser toes." The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 53.4 (2014):

- ↑ Gajdosik, RL, et al., A stretching program increases the dynamic passive length and passive resistive properties of the calf muscle-tendon unit of unconditioned younger women. Eur J Appl Physiol.

- ↑ Maceira, E. et al, Analisis dela rigidez metatarso-falangica en las osteotomias de Weil. Revista de Medicina y Cirugia del Pie.

- ↑ Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8

- ↑ Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8

- ↑ Espinosa, Norman, Ernesto Maceira, and Mark S. Myerson. "Current concept review: metatarsalgia." Foot & ankle international 29.8

![[1]](/images/thumb/5/5f/Metatarsalgia.jpg/435px-Metatarsalgia.jpg)